18th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration - Margaret A. Burnham, “The Dream and the Reality”

[MUSIC PLAYING]

LAWRENCE: Good afternoon. My name is Deirdre Lawrence. I'm a PhD candidate in the Division of Toxicology, President of the Black Graduate Student Association. I will be your mistress of ceremonies. I would like to invite Father Bernard Campbell to deliver the invocation.

CAMPBELL: The dominant imagery of relationship among human beings and between human beings and the mysterious God of the Bible is not that of a contract. Contracts bespeak in human experience, and necessarily, limited commitment. They are strictly limited to the persons who sign on. Limited too both in the promises made, and the timing for the completion of the agreement.

The Bible on the other hand, speaks of relationships more daringly. A whole, not partial heartedness. characterizes the central image covenant. The mysterious God promises, I will be with you no matter what you do. I will remain faithful to you. This indeed is the strangest of all the gods.

And humankind, stunned by that fidelity, is invited to memory, action, and hope. Remember, you were once widows, orphans, strangers. So now, care for the weak in your midst, and do so without losing heart. In that memory, passion for justice and hope, we gather to celebrate one of the mysterious God's most faithful covenanters, Martin Luther King Jr.

Lord God, you who hold all our names etched in your hand, who will not quench the flickering flame or break the bruised reed, bolster us with your fidelity, that our memories not merely be custodians of nostalgia for the good old days, that our passion for justice be wide and deep, and not simply the trickle of just us. And that through all the bitterness of human folly, help us to remain of one mind and heart with you, amazed at the dignity of the human person, made in your likeness and image. Amen.

LAWRENCE: Now, Turquoise Gosman, a student in the MIT Wellesley Upward Bound Program from Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School will extend a warm welcome.

GOSMAN: To President Vest and to our esteemed guest speaker, Judge Higginbotham, and to the other members of today's program, and to you, our audience. I bid you a fond good afternoon. My name is Turquoise Gosman. I'm a student in the MIT Wellesley Upward Bound Program, and a sophomore at Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School.

It is indeed a privilege and an honor to welcome all of you to MIT's 21st annual celebration of the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I am honored to be included in the special celebration for such a wonderful civil rights leader. We've come here today to show our appreciation for someone whose work and talents seem to be remembered only on one day in January and during Black History Month. Dr. Martin Luther King and his beliefs should be remembered every day.

This was a man the great civil rights leader. He tried to make a better lives for all races. This was not a man who believed that there were only black and white races.

Dr. King was a man who believed that our races were equal and deserve recognition and respect. No Martin Luther King Jr was colorblind, but he chose to be. Martin Luther King did this in hopes that we as a nation would see people for who and what they are, and not judge people by the color of their skin.

There are many words I could use to describe this unique individual, but I don't think they would or could sum up to what a remarkable person he was. To those of you who have known Dr. King, you are blessed through your memories of him. But for teenagers like myself and the children of the future, I pray that Martin Luther King's dream lives on. And so, I leave you with a quote from Dr. King's address, The American Dream.

And there is another thing we see in this dream that ultimately distinguishes democracy and our form of government from all the totalitarian regions that emerge in history. It says that each individual has certain basic rights that are neither conferred by, nor derived from its necessary-- from the state. To discover where they came from, it is necessary to move back behind the dim mist of eternity, for they are God-given. Very seldom, if ever in the history of the world, has social political document expressed in such a profoundly eloquent and unequivocal language the dignity and the worth of human personality.

The American dream reminds us that each man is heir to a legacy or worthiness. So please sit back and relax as you focus on today's celebration theme, the trumpet of conscience. Dr. Martin Luther King's contract with America. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

LAWRENCE: Allow me to bring your attention to Chris Richman, who is a student in the Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering. He will accompany us as we stand together and sing, Lift Every Voice and Sing. We're going to sing the first and third verses, and the words are printed on the back of your program.

[MUSIC - "LIFT EVERY VOICE AND SING"]

I am pleased to announce that another segment has been added to our program. And that is the presentation of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Leadership Award. This award is presented to MIT graduates who have distinguished themselves by incorporating Dr. King's legacy in their professional careers, and through community action. The award committee also recognizes individuals and groups within the MIT community whose achievements exemplify the ideals of Dr. King by their contribution to MIT, and the broader community. At this time, I call upon Provost Mark Wrighton to make the first presentation to Professor Robert Mann.

[APPLAUSE]

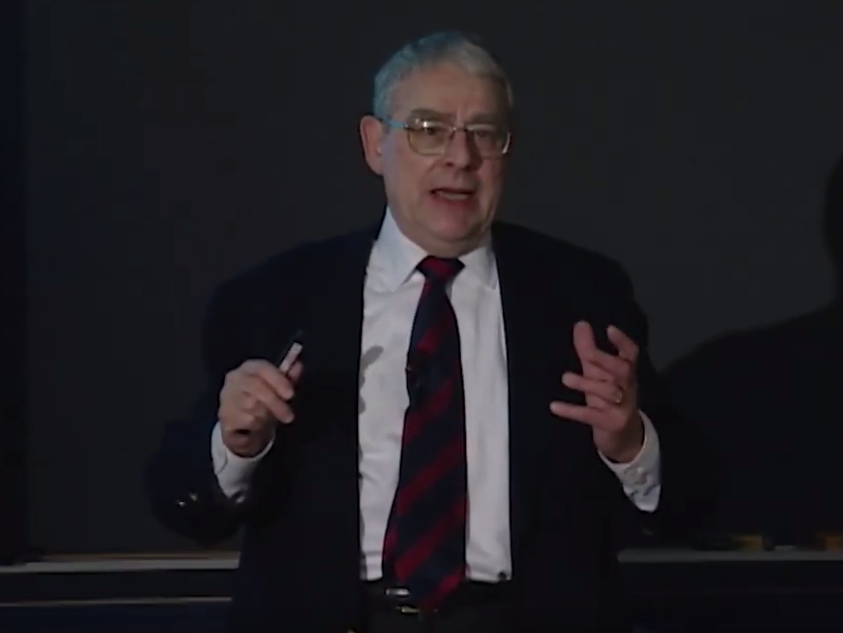

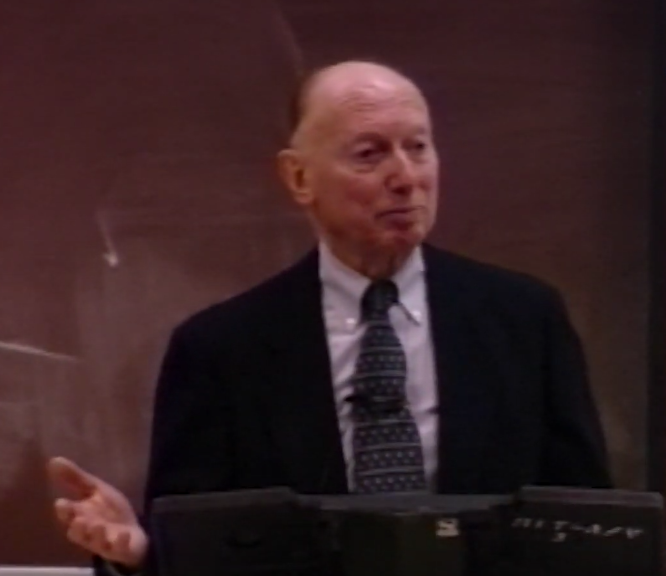

WRIGHTON: It's a great honor for me to make the first presentation of this important series of awards, and to such a distinguished individual as Dr. Robert W Mann. I'd like to ask Dr. Mann to come forward as I introduce him to you. He will be making a few remarks in just a moment. Dr. Mann is a longtime contributor to the MIT community, retiring only just a couple of years ago as Whittaker Professor. He continues a very active set of activities on behalf of the Institute, and in his personal life.

He began an interest in technical activities early on in his life. He graduated in 1942 from the Brooklyn Technical High School. As you can appreciate, 1942 was a difficult time for the country.

He went to work shortly thereafter as a draftsman at the Bell Laboratories, and then joined the army in 1943. In 1946, he concluded his service in the Army, having worked in the teletype and cryptographic maintenance activities in the Western Pacific Theater. And then he commenced what became a truly distinguished career at MIT.

He received his bachelor's degree in 1950, continued on for the master's degree, and concluded in terms of formal education with a Doctor of Science in 1957. Already a member of the faculty for several years by that time, he was promoted up through the ranks and concluded his career-- as I've indicated-- as Whittaker professor. During this distinguished career, he became extremely well recognized for his contributions in the Department of Mechanical Engineering as an educator and as a researcher.

He was named to the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine. Just several of his distinguished honors. Here at MIT, he received the Killian Faculty Achievement Award-- our highest award for the faculty-- in 1983.

And in 1983 to 1984, he served the Alumni Association as its president. He has more than 320 publications, several patents, and a number of his activities in the professional arena have contributed to aiding the blind and assisting the disabled. His work in biomechanics can be credited with creating an entire new field of human endeavor.

Professor Mann has also been a very important contributor to his community. In the town of Lexington, he served as a member of the town meeting from 1954 through 1958. He was director of the interfaith Housing Corporation for 10 years. And he has continued that kind of service within the MIT community as well.

In recognizing him as a Martin Luther King Jr Leadership Awardee, we recognize a large number of years, and an enormous amount of service in connection with these celebratory events. Indeed, a few years back, at a time when this activity was at a low point, he encouraged then president Paul Gray to reinvigorate this program.

And Robert Mann can be credited with the enormous success that we have realized now for more than 20 years. Let me now make the award presentation. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Leadership Award is presented to Doctor Robert W Mann, class of 1950 at MIT, whose achievements and contributions exemplify the ideals of Dr. King. February 10, 1995.

[APPLAUSE]

MANN: I am, of course, greatly pleased and honored, in fact, humble in addressing you after that introduction, and with the significance of the first time recipient as a faculty member of this recognition. And I had a little notice, and I'm told I have two minutes, and I debated a bit as to quite how to handle that. I haven't vetted the most recent version with my wife, but let me try it this way.

The suggestion was that I relate aspects of my career that overlapped that of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I had the great privilege-- not many of you out there I think can share, certainly the young people can't-- of personally having heard Dr. Martin Luther King when he addressed the people of Lexington in the 1960s at the Lexington High School. But I think we share some other dimensions, which I am convinced has put me here in this position with this recognition today.

To begin with, we both come out of a tradition-- a religious tradition-- that is entering its third millennia, which is committed to the belief that every human being from conception on is a unique individual, and as such, is deserving of the respect of all other human beings. We perhaps have somewhat of a shared experience in origins. I grew up in a tough but nevertheless, multicultural and multireligious section of Brooklyn, New York, East New York. And early on, was aware of the variety of colors and religions and postures that people had,

So as I accept this award, I guess I want to say I do so with the realization that it was easy for me-- relatively easy for me-- to experience the kind of opportunities that I had, or capture-- utilize the kind of opportunities that were presented to me because of this background of both religious conviction, and of early development. These were of course, greatly strengthened and matured through my now almost 45 years association with Margaret Mann.

And very exciting years in the 60s when Vatican II was in process, when Martin Luther King was on the march that you all know about, when our curates in our parish in Lexington were arrested for marching in North Carolina. It was a very exciting time. So it's easy for me to have played the role that I have.

And what I want to do is accept the award in the name of all of you there and elsewhere who could equally well be here with me, or replacing me on this occasion. Many of you whom have not had the same kind of opportunity and development, maturation, motivations that I have had the privilege of enjoying as I have pursued the various activities that Provost Wrighton has so graciously described. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

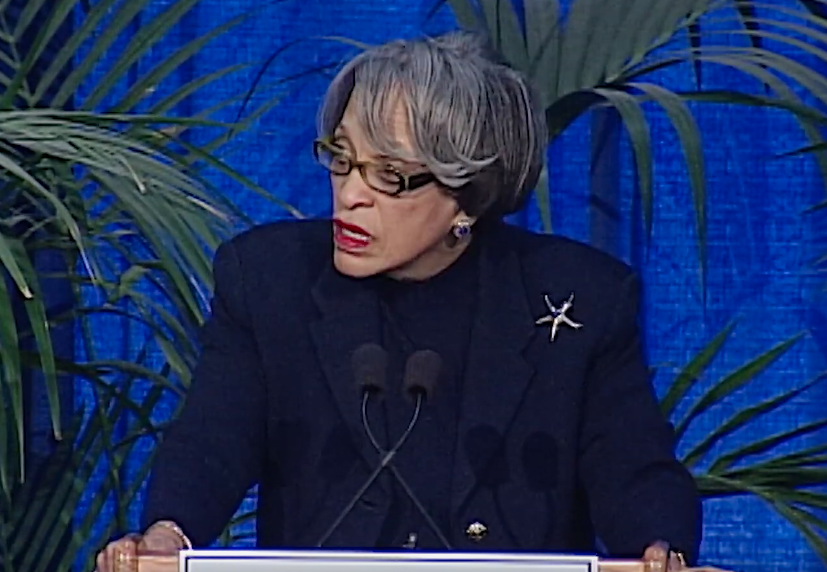

LAWRENCE: Now I will ask President Vest to present the award to Dr. Cynthia McIntyre, and to AISES, NSBE, and SHPE.

VEST: Dr. McIntyre, would you like to join me? It's my pleasure and privilege to present four additional 1995 Martin Luther King Jr Leadership Awards, which are being given-- as you know-- for the first time this year. The Martin Luther King committee developed this concept to recognize past and present members of the MIT community whose activities exemplify the ideals of Dr. King.

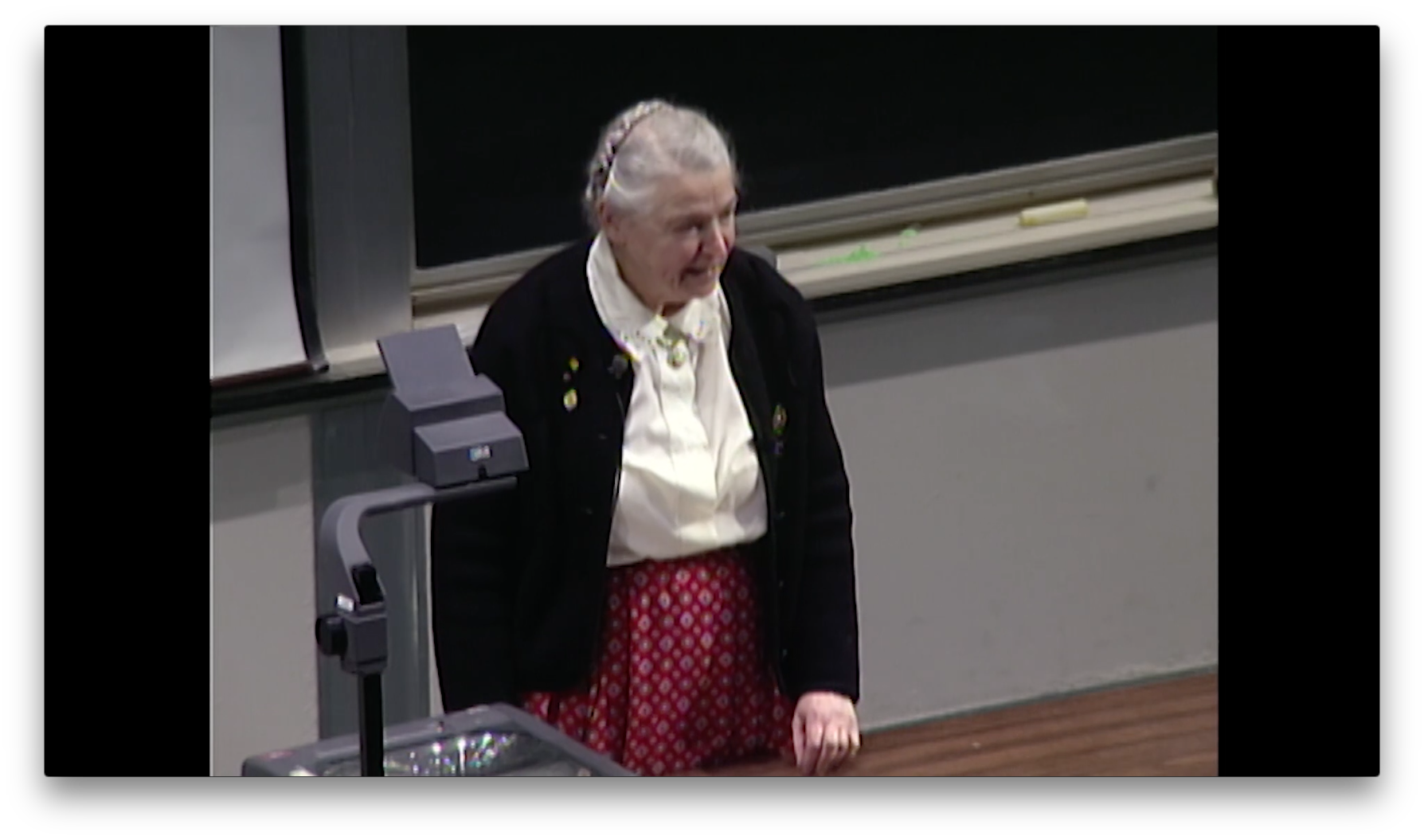

This year, we are presenting awards both to individuals, and to student groups. The individual recipient is Dr. Cynthia McIntyre. Why don't you step out into the light? Not back in the shadows. Thank you.

Dr. McIntyre pursued her PhD research here at MIT in the area of condensed matter physics. In addition to her academic work, Dr. McIntyre served as a member of the Physics Graduate Student Graduate Committee, and also as a resident dormitory counselor. However, one of her primary contributions was originating and organizing the National Conference of Black Physics Students.

She had noted the small number of black physicists in both academia and industry, and wanted to increase that number by reaching out to students still in the initial stages of their academic careers. The conference brought together undergraduate physics students from colleges and universities nationwide to discuss career options and career strategies.

The conference was a resounding success, and since has become an annual event held at different universities around the country, with attendance rising to over 200. Dr. McIntyre has provided leadership, vision, and support for the conference throughout this entire period, and has done so with her characteristic energy, creativity, and above all, passion for making a difference in the lives of young people, and of somewhat older institutions. Dr. McIntyre, it's truly a pleasure to present this plaque to you and the accompanying honorarium.

[APPLAUSE]

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Leadership Award, presented to Dr. Cynthia R McIntyre, class of '90, whose achievements and contributions exemplify the ideals of Dr. King. 10 February. 1995.

MCINTYRE: Thank you.

VEST: My thanks, and congratulations.

MCINTYRE: Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

I'd like to thank the committee for selecting me for this honor. I'm very grateful and proud to have this. One thing I wanted to say-- Leo told me that I have one minute to speak on this-- is that Dr. King's legacy head a tremendous impact on our educational system, particularly higher education.

You can see throughout the country that our universities are quite diverse. Whereas 20 to 30 years ago, the dominant institutions, academic institutions, did not have a substantial number of minority students in their programs. But now they do, and that's part of Dr. King's legacy.

Another part of Dr. King's legacy is the growth of the number of PhDs in physics over the 20 year or so period since the 60s and 70s. During that time, the physics department here at MIT made a commitment that they would have black students in their PhD program. And so during that time, they graduated quite a few.

And a lot of you don't know the statistics, but if you delved in a little bit, you would find out that there are three institutions in the United States that have graduated most of the PhD-- black PhDs in physics. And MIT is one of those schools. The other is Howard University, and the other one is Stanford. So MIT has made a tremendous contribution to the black scientific community in the area of physics.

When I was here as a graduate student, a group of us got together and decided to put on this conference. And we said, well, how are we going to pull this off? We need money. We need money, and we need money to get students here, and to get this started.

So what we did, we had a little plan together. And we went to the chairman of our department, Dr. Jerome Freeman. Would you stand up, please?

[APPLAUSE]

And we said Dr. Freeman, we want to put on this conference. It's a national conference. We think we can get maybe 40 or 50 students here for this, and here's a budget for it. He didn't say, well, come back tomorrow, next week.

He said, it's done. We'll do this. I'm calling the dean-- who at the time was Gene Brown. He said, I'm sure the dean is going to back this. From the physics department, you have a commitment today. I will get back to you tomorrow and let you know what the dean said.

And we've been off and running ever since. Thank you. Thank you for your support.

[APPLAUSE]

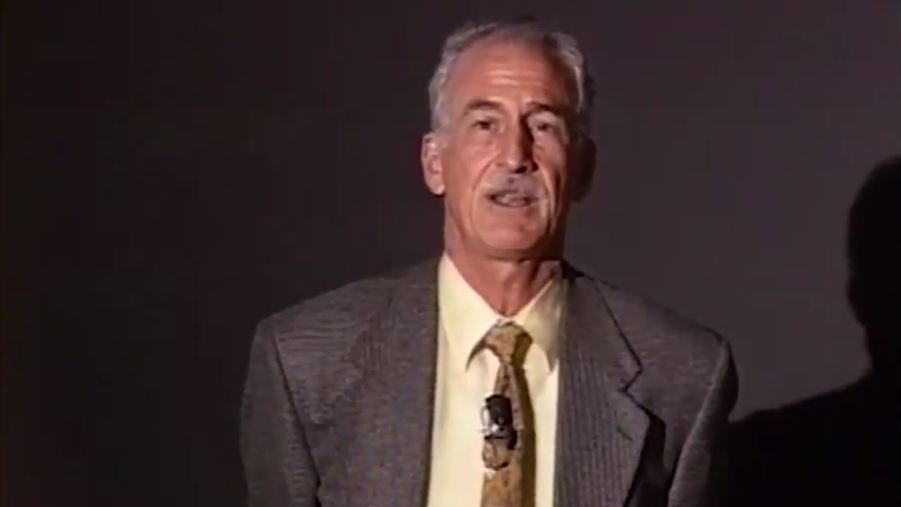

VEST: Could I ask the three presidents to join me now, please? All three of you. Three professional organizations also were nominated for awards. These are the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, The National Society of Black engineers, and The Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers.

Since 1990, these three organizations have jointly sponsored a career fair at MIT for the entire student body. The event has become the largest student-sponsored career fair at the Institute. The sixth fair will be held later this month on February 23, and 24. These three organizations representing students from various ethnic groups have worked together for the benefit of the entire student body. They show by example what can be done when different groups work together for common goals.

And David Shaw, associate director of the Office for Career Services and Professional Advising said of these groups-- and I quote-- "Their effort and cooperation have exceeded most other professional organizations that I've advised over the past 25 years." I would say that this is the case. The whole is truly more than the sum of its parts, and we are all the better for it. I'm very pleased to have the privilege to present plaques and honoraria to the presidents of these three groups.

To Stephen T York of the American Indian Science-- and Science Engineering Society.

YORK: [INAUDIBLE]

VEST: To Charita D Williams of The National Society of Black engineers. And to Jeff O Gonzales of The Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers.

GONZALES: Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

VEST: Congratulations to all of you.

YORK: Thank you President Vest for the award on behalf of AISES. My name is Todd York, president of the MIT chapter of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society. Currently, I'm a junior in chemical engineering.

First, let me give you some background information on the beginnings of the career fair. The idea for the career fair came about from a mutual need between our respective communities and one administrator. We three organizations-- AISES, NSBE, and SHPE-- felt that we should provide our members and the MIT community with opportunities beyond their academic life at the Institute. These would include graduate school, a necessary component for students of color to succeed in the workforce, and job opportunities with government and private organizations.

The career fair would be a combination of events throughout the academic year. As organizations, we knew that the success of our members would not only depend on information received in the career fair, but also in the development of skills that can be used in a variety of fields. With the resources of the Institute, we would assist our members with national fellowships for graduate school, resume writing skills, and interviewing techniques.

It would also be important for all three organizations to work together as a group to maximize Institute resources, and more importantly, to learn from each other. It would be this cooperation from these three very different professional organizations that would be critical to the success of the career fair. Once again, on behalf of AISES. Let me thank the president and the planning committee for this Leadership Award. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

WILLIAMS: Good afternoon, everyone. My name is Charita Williams. I'm president of the MIT chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers, and a junior in electrical engineering. I would like to share with you the uniqueness of the career fair and how it relates to Dr. King's legacy. Our minority career fair is a joint effort between three very different organizations, each with his own mission, membership, and programs. Still, we have crossed social barriers and put aside individual differences to come together and produce the single most important financial event for each of our organizations.

Each group shares both the responsibilities and rewards every February, when over 60 companies come to MIT seeking their future leaders. The membership of AISES, NSBE, and SHPE are truly helping to fulfill Dr. Martin Luther King's dream. Because part of the dream is for people of different ethnic backgrounds to work together as brothers and sisters toward common goals and share success.

Our collaboration for the career fair is not our only testament of dedication towards this brotherhood. We've also worked together to host a very successful social for the entire minority community, and we've joined forces several times recently to address problems common to the minority community MIT. Although we still have a long way to go before we see African-Americans, Native-Americans, and Hispanics sitting together for lunch, we have made significant progress in reaching out to one another for common issues. Again, I would like to thank everyone on behalf of NSBE, AISES, and SHPE for recognizing our efforts with this award.

[APPLAUSE]

GONZALES: Again, my name is Jeff Gonzalez. I'm the president of SHPE, the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers. A dream is a beautiful vision that-- a dream is a beautiful vision that looks beyond what you can see, then lifts you and guides you and grows strong inside you to help you be all you can be. As we approach the 27th anniversary of Dr. King's passing, we still are looking to achieve his dream as we confront obstacles in our way. It is the role of organizations such as AISES, NSBE, and SHPE to show that we can work cooperatively to lead the way in removing these barriers.

Dr. King's legacy has given us an opportunity to learn at an institution as renowned as MIT. I feel it is our obligation to continue his ideals and assist those who will follow. However, I don't always see the sense of commitment from my fellow students.

To reverse this, we must follow Dr. King's dreams and ideals. Because as he stated, freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. It must be demanded by the oppressed.

On behalf of AISES, NSBE, and SHPE, we would like to thank President Vest and his planning committee for the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr celebration activities for this Leadership Award. We also like to thank our respective advisors and other members of the three organizations, past and present. And finally, I invite you to attend our six annual career fair to be held February 24 at Dupont Gymnasium from 12:00 to 6:00 PM. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

LAWRENCE: It is my pleasure to introduce Professor Markus Thompson, who was the first recipient of the Robert R Taylor Professorship. Today, he'll be joined by MIT students to perform the musical selection, Music of Morning. The students that will be joining him are Julia Ogrydziak, Donald young, Danny Yu, Joel Dawson, Leonard Kim, and David Reilly.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC - "MUSIC OF MORNING"]

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you. That was amazing.

[APPLAUSE]

At this time, I'd like to invite President Vest to give his welcome remarks, and he will introduce our keynote speaker.

VEST: As I look over the past year, I can take note of several people and programs that make this celebration much more than simply a one day event. Some are causes for celebration, and all our causes for inspiration. Inspiration to work harder, and to work together to achieve a greater racial and ethnic harmony, and a greater social and economic justice in our society.

I suggest that we dedicate this year's ceremony to one such source of inspiration. To Bill Ramsey, whose death last month was so unexpected. Bill was executive director of special programs in the School of Engineering. In particular, he was responsible for the administration of the MITES program, which stands for Minority Introduction to Engineering and Science. And the engineering internship program, in which students combine academic programs with on the job experience.

Bill was the very model of dedication, professionalism, honesty, caring, and fairness. He was a mentor and a role model to literally hundreds of our students. Their success and contributions to society are Bill's legacy. His death is a tragic loss to his many friends and family here, and to this institution as well. Bill's work and his way of working are sources of inspiration to all who strive for a better society.

Our society, of course, begins right here on our campus. This is where we begin. And what I think we need to do much more than we have been doing is to build coalitions among the individual groups that make up our community. Because working for equity and justice is not the responsibility of any one person, or any one organization, or any one cultural group. In fact, we simply won't succeed if different groups, whether African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, or white Americans work on these issues in isolation from each other.

Now, working together in coalitions is not always-- indeed, not often-- a comfortable experience. It means that you bring your ideas and your interests to the table, of course, but that they don't carry any more weight than those of the others. It means that some interests may be in conflict with each other.

It means having to listen, really listen, to what others say about their experiences and their expectations. It means learning from differences. It means learning to trust, and then working to find common ground.

This is hard work, so why should we do it? The answer is simple. There is no other way.

There are those who ask why we should bother trying to build racial and ethnic relations at all. Why not just live and let live? I would guess that different people have different answers to that question. But for me, the answer is quite simple. We need each other.

There are more problem in the world than there is time to list them. But one thing is clear, successful resolution of the problems getting in the way of social equity, economic justice, public health, or environmental health just to name a few, requires people to work together. You can't solve the problems of this complexity and this magnitude and scale by yourself, whether you refers to a single organization, a profession, a class, or even a race.

We are realizing this more and more in the way we teach and learn. Not only is learning in teams, whether it be in the 270 design contest, or the team's work experimental program in chemistry, often more effective is much more like the world in which our students will live and work after graduation. So yes, we need each other.

Not only to solve problems, but to grow. To grow in our understanding of the world around us, and the world within us. Everyone in this room can expect to live and work in a world filled with people of different cultures, races, and nationalities, whether you stay right here at the Institute, or live halfway around the world. If we are to make the most of this world and what it has to offer, professionally, socially, and ethnically, we need each other.

And it's worth the struggle. It's worth the work. I believe very much it's an investment that will pay off.

There are many on this campus who are making just this kind of investment. One, of course, as you see today, is the planning committee for the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial activities. These men and women from many parts of the Institute do not see change in narrow terms. Not only do they plan this annual ceremony, as you've heard, they initiated the awards program that we just inaugurated. And it was their proposal that led to the very recently announced Martin Luther King Jr Visiting Professor Program.

The goal of this program is to enhance and recognize the contributions of minority scholars by increasing their presence and interaction here on the MIT campus. We hope to appoint several such visiting scholars each year. We expect that they will deeply engaged themselves in the intellectual life of the Institute through teaching, public lectures, seminars, research, and scholarship. This program will have a significant effect on the number of minority scholars who join our faculty ultimately on a permanent basis.

Another group that is making a solid investment in our future as a campus community is the Committee on Campus Race Relations. MIT announced the establishment of this committee at last year's Martin Luther King ceremony. In its first year, the committee, drawn from a broad cross-section of our community, has done a great deal to help build the very kinds of coalitions I've mentioned, beginning with its own membership. Beyond that, it has published a guide to studies in racial, ethnic, and intercultural relations at MIT. A document that is, in itself, an impressive indication of faculty commitment and student interest in these areas.

The committee also has established a grants program, which even in its first year, has funded lecturers, arts activities, cultural and ethnic events, dorm-based activities, workshops, conferences, and undergraduate seminars, all with the underlying aim of enhancing race relations on our campus. These are but two small examples of the work that we all need to do. There are many, many others, as you know. But we need still more people to make the commitment and to make the investment that will turn our campus ever increasingly into a true community.

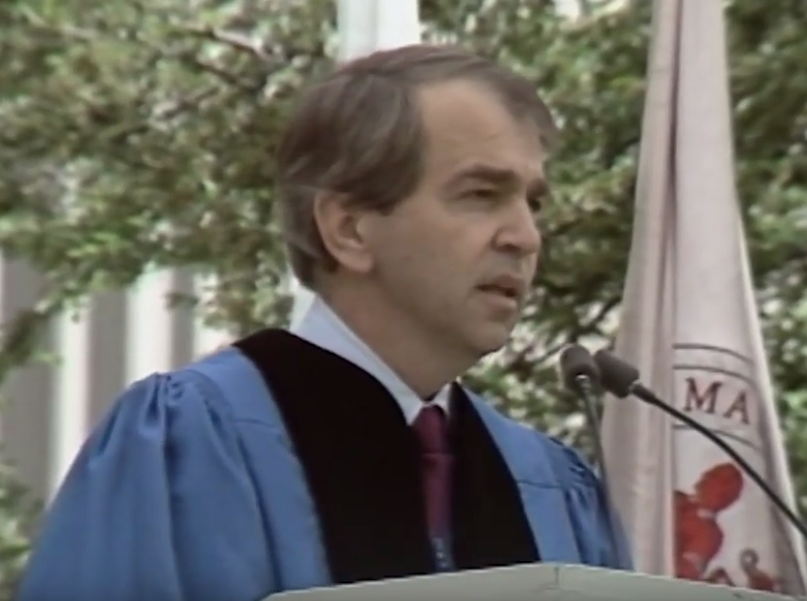

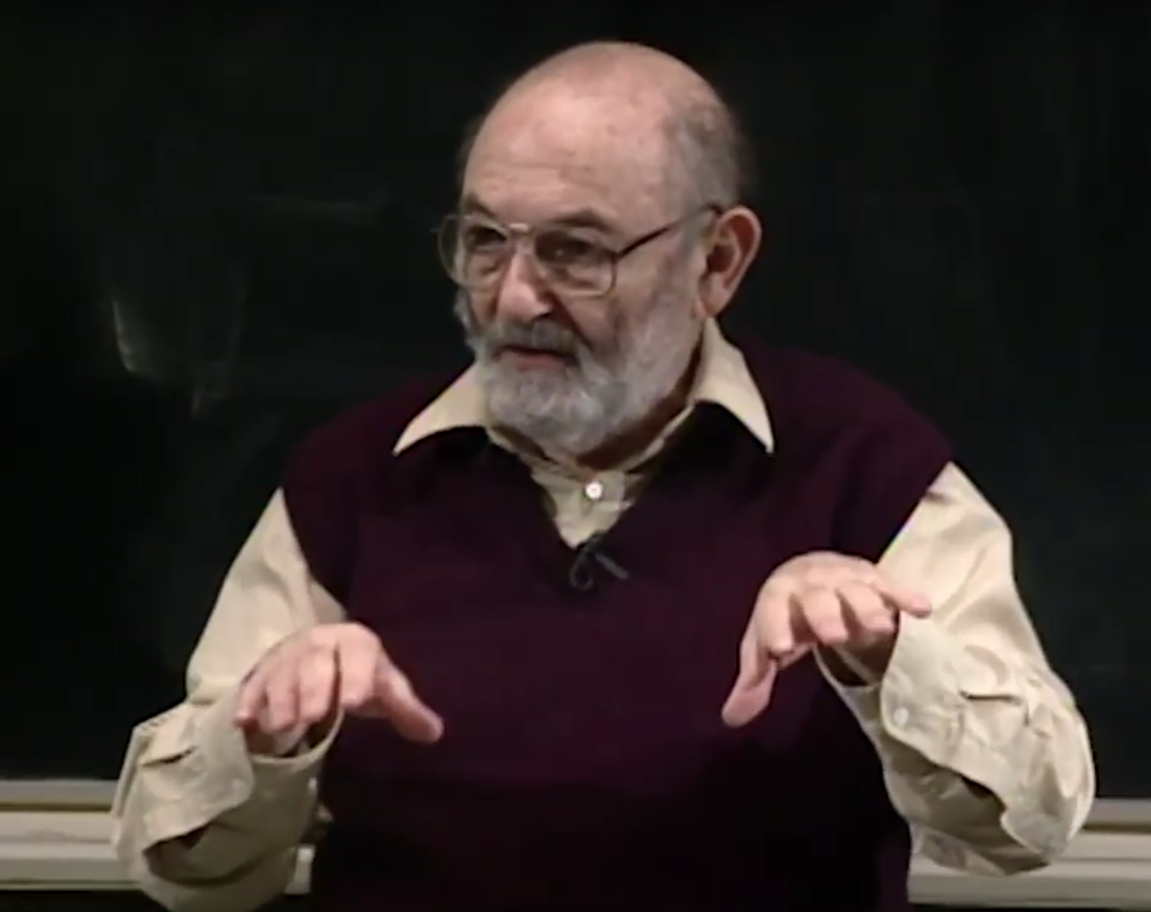

And now it is a very special privilege to introduce today's keynote speaker, a man of many facets who has devoted his career to the pursuit of racial harmony, equity, and justice. It is truly a great honor to have Professor A Leon Higginbotham with us today. He is, of course, a truly distinguished jurist. The Chief Judge emeritus of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third District.

But he is also a teacher and a scholar. Currently, he's public service professor of jurisprudence at Harvard University. And he has served as an adjunct faculty member at several leading universities throughout our nation. He is an author and a historian. His book, In the Matter of Color, Race and the American Legal Process, The Colonial Period, received several national and international awards for the quality of its scholarship.

He continues his association with the practice of law serving as counsel to Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, and Garrison in New York's-- in their New York and Washington offices. Let me say finally-- and rather personally-- that Professor Higginbotham is a true friend and colleague to our institution. Many here today will recall that a few years ago, the Justice Department brought an antitrust action against MIT and the Ivy League universities, alleging collusion in the way we awarded financial aid to students.

We on the other hand, argued that our practices sought to ensure that students would be awarded financial aid solely on the basis of their need. And that different schools would not get into financial bidding wars for students. We lost in the first round of that legal battle back in the fall of '92, but we appealed it. And that's where Leon Higginbotham stepped forward.

He had retired earlier in that year from the appeals court in Philadelphia, which in fact, was the one hearing the case. He returned to appear before that very court on behalf of the Philadelphia School System, the Urban League of Philadelphia, and the Coalition of Bar Associations of Hispanic, Black, and Asian-American Attorneys in the Philadelphia area. These groups-- I quote Judge Higginbotham as saying-- "These groups are the counsel for the interests of those bright and very needy students who would be most adversely affected by the lower court ruling."

He told the panel of judges, "We have in this case public service and ethical norms. And what are those ethical norms? They are that those people who are weak and those people who are poor but who are talented should have the same opportunity to have an entry into these great universities as did the Kennedys, and the Rockefellers, and the Cabots, and the Lodges."

This concern for ethics and equity permeates Leon Hornbeam's life and his work. He will speak to us today of a contract with America that we would do well as a nation to honor. It is Martin Luther King's contract with America. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Judge Leon Higginbotham.

[APPLAUSE]

HIGGINBOTHAM: Dr. Vest, Provost Wrighton, the members of the MIT community who have made such a significant difference. I was profoundly moved in a way in which I seldom am when Dr. McIntyre mentioned the chairman of the physics department has said, it's done. Because it's a classic example of what administrators can do. They can help us solve the problem, or they can filibuster as to why it is so impossible to solve it.

At the age of 16 years old, I was interested in physics. And I was interested in electrical engineering. And I had, as a poor boy, the temerity to believe that I could make a difference as an engineer.

And I went to Purdue University. And at Purdue, there were 13-- as we called them then-- colored, or maybe Negro, but never black students. And we stayed at a place which was called International House. International? All the black kids at an International House?

Well, let me tell you about the luxury we had in the International House. We all slept in an attic with no heat. And during those bracing, terrible, biting winter nights, we'd go up to bed with shoes on, earmuffs, two or three layers of pants, and hoping that we would then be able to be warm enough the next morning to go and study about the dechlorination of chlortetracycline, and to study all of the challenges which we had.

One night, I felt that I could not stand another day. And I talked to my fellow students, and suggested that we should visit Dr. Elliott, who was then president of the university. I won't get into the side details. Everyone was unanimous that a protest should take place, that I should be chairman, and we would all show up.

Well, I went and I arranged the appointment. And then the next day, I went 15 minutes before the time I was supposed to meet the president. My one shirt was ironed, I had done it. My shoes polished. My fingernails clean.

My mother-- who was a domestic-- had always stressed upon me of making the best of what you have. And I went in to see Dr. Elliott. It was 10 of 10:00. It was five of 10:00. It was three of 10:00.

And all of these militant students who were going to meet me there for some reason got tied up in some lab or something. And here I am, meeting the president. He says, Higginbotham, what do you want? It wasn't welcome.

And I said, Dr. Elliott, every day colored soldiers are dying fighting Hitler and Hirohito for what President Roosevelt calls the four freedoms. And we are freezing in that dorm. And we want to be good students. Is it possible that we could have a section of the dorm?

I wasn't pressing to get the place integrated. Just a section of the dorm where we could be like the others and be warm. Elliott looked at me and said, Higginbotham, the law doesn't require us to have you here. You either take it or leave it.

And I walked out recognizing the profound contradictions. The preamble of the Constitution said we the people of the United States. But in Dr. Elliott's eyes, they were we the people, and we the other people. And I was part of the other people. And ultimately, I left-- though I was performing quite well academically-- and transferred to Antioch College and went on to Yale Law School.

If Dr. Elliot had said to me what the chairman of your physics department heads said, good morning. I would have felt a little better. And if he had even said to me, well, Higginbotham, I don't know whether we can do it, but we should. Blunt no.

And when I sometimes think of why there aren't more scientists and more engineers today, it's because of the experiences which so many of us had in the 1940s. It did not seem to be a viable option. So when MIT got involved with its difficulties, when the United States Department of Justice, when it had the opportunity to challenge all of these mergers going on with conglomerates, global conglomerates, and did not challenge them, and as the country was becoming more oligopolistic all of the time, Dick Thornburg, the Attorney General of the United States, a few weeks before he's about ready to resign and run for Senator of Pennsylvania, filed suit against the Ivy League schools challenging the type of arrangement they had.

Which I assure you meant that need came first, and therefore, if you base it on need, more and more students could come in. Need for students who had already been accepted. And for some strange reason which I shall never know, the Department of Justice during the Bush administration prosecuted the eight Ivy League schools and MIT.

And in the speech-- which I will give for your book-- I have the extensive comments of the newspapers throughout the country, which looked at this suit and thought that it was incredulous. The New York Times described the suit as a destructive claim unworthy of litigation. The Washington Post said that the case against the Ivy League and its friends may be good sport, but it's bad policy. The Los Angeles Times in an editorial on May 24 called it pure lunacy. And The Boston Globe characterized it as a twisted interpretation of the Sherman Act.

And I could go on. Yet, when I was approached, the case had not been won. Even though you had the most able and extraordinary attorneys representing MIT, who had made arguments which I submit to you were irrefutable. And when it was suggested that maybe that I would go in as counsel for the [INAUDIBLE], pro bono publico, that means for the public good. And I'm pleased to say, without any compensation.

And I thought that this was an opportunity for me to say to a school which was treating students differently than the way Dr. Elliott treated me that you are on the right path. And that pluralism is important in America. And that if you allow this antitrust suit to prevail, would mean that children who are needy, or students who are needy, who could not meet the extraordinary tuition may not make it. Because if you just distribute the pot in some random fashion, one person may be getting 15,000 when they only need 10. And if you keep doing that for several, it means that on the other end, in a world of limited resources, those who are poor and needy would drop out.

And we were fortunate enough to be successful. Last year was a great year for me. My two most important clients did not pay me. MIT, and Nelson Mandela.

[LAUGHTER]

[APPLAUSE]

But both have made profound differences in this world. I don't know why my good friend Clarence Williams was so generous to ask me to come back here to speak again. I've been in this auditorium more than once.

I spoke at your tribute 13 years ago for Martin Luther King. And at that time, Ronald Reagan was in his first term as president. At that time, no one knew then that Dan Quayle did not know how to spell the word potato.

[LAUGHTER]

And at that time, William Jefferson Clinton was not known outside of Arkansas. The Soviet Union was still a formidable adversary. And Nelson Mandela was serving the 19th year of his lifetime sentence breaking and chipping stone at the cruel Robben Island Penitentiary.

And in 1983, I thought that even then, that the conditions for the weak and the poor were bleak. And I was not convinced that that safety net which President Reagan had assured us was there would be holding up the homeless, the hungry, and the poor. And I said, how can you talk to one of the most sophisticated audiences in the world? You've got to not harangue them. And how can you give them something which we can all relate to in abstract?

So I asked the audience to imagine and to assume that the MIT Department of Astronomy was the most able in the world. And there were no dissents. And I suggested to them that maybe it was possible that this great department had developed the capacity to do electronic eavesdropping in Heaven. That place I would not take time to define, and if you don't know where it is, and you don't believe there is a Heaven, it would be a waste of my time to stress it to you.

But then I worked up a conversation an imaginary conversation. It was a fantasy, I know, that your extraordinary department had gotten the electronic eavesdropping system working. And then we heard a conversation between Martin Luther King and Tom Jefferson.

We heard King speaking to Thomas Jefferson. He said, Mr. Jefferson, since we have such equality here in Heaven, do you mind if I call you Tom? Now, Tom, how is it that individuals who are as philosophical and profound as you, and as brave as George Washington, and as eloquent as Patrick Henry could treat an entire group of people-- non-whites-- with such special harshness and cruelty solely because of the color of their skin?

And there is this fascinating dialogue where Jefferson admits that he was wrong. And he thanked Saint Peter for the Affirmative Action program they had in Heaven.

[LAUGHTER]

To bring a little more diversity, and to get some lawyers and politicians in there, because there was such a shortage. And now, 13 years later, I stand before you, in the presence of an audience equally as sophisticated. And I did not know what I could say, what I should say. But yesterday morning, I had another mystical and miraculous experience. I give it to you with some trepidation, because I don't know how many of you are believers.

But I was reading the paper while drinking a cup of coffee in my study. I had the television on CNN. I was reading about the OJ Simpson case.

And then I gradually became aware that the television in front of me had stopped transmitting its usual message. I am so cheap that I have a black and white television in my study. Instead, the screen was multi-colored.

And as I tried to fine-tune the screen by playing around with the remote control, suddenly, there were a series of scenes which began to unfold. And I saw the image of a white building framed with columns and surrounded by greenery. The camera started to move towards the building and suddenly, I had a view of the interior. And in the interior it had on it the Abraham Lincoln and Thurgood Marshall seminar room in Heaven. And the door swung open as if by some mysterious force, and inside, I saw the interior of this seminar room.

And on the blackboard written in huge black letters were the following, seminar at noon today. Martin Luther King, speaker. Thurgood Marshall, moderator. A Leon Higginbotham, junior transmitter.

And I could not believe my eyes. Here was King on the podium. And in the audience were people whom I admired so greatly. Sojouner Truth, and Earl Warren, and Charles Hamilton Houston, William Henry Hastie, and Abraham Lincoln, and a whole series of individuals-- Rabbi Prinz-- who've made a great difference.

And as I saw this, I started to wonder, was I going through some unusual syndrome? My wife had been telling me that I'm working too hard. And then after seeing this, my fax machine went on automatically. And we always have white paper. And coming out on our fax machine was blue paper.

And the fonts were larger than any I thought our fax had a capacity for. And on the front page there were just two words, from Heaven. And on the second page in slightly smaller type was the byline, for Martin Luther King Jr entering class of 1968.

The printer was going so fast that the paper was almost ablaze. It was so hot that I could not hold it comfortably in my hand. And nevertheless, I'd read every word. And

Just after I finished the last page, suddenly, whiff. All of the ink disappeared. The paper started to disintegrate into ashes. And the TV screen reverted back, making reference to the next day of trial with OJ. Dazed and confused, I rushed to my desk and started scribbling down the miraculous events I just witnessed.

Now, I cannot provide you any documentation, any independent covert corroboration to what I saw from Heaven on my TV screen. And the fax paper went into ashes, which cannot be reconstructed. But I'm confident that I saw Martin Luther King speak. And through the television, I received a commentary from him that he wants me to transmit to you, and to Newt Gingrich.

[LAUGHTER]

And it is exactly what I would've expected to see and hear from Dr. King. And let me describe to you how it starts. My dear brothers and sisters, I prepared my commentary for this afternoon as an open letter to my fellow citizen of Georgia, Newt Gingrich. And I'm hoping that my old friend Leon Higginbotham will forward it to him soon, and deliver the substance of my comment in his lecture today at MIT. More important, I hope thoughtful Americans will recognize what may very well be one of the most tragic hopes and potential cruelties that could take place in America, and to what Mr. Gingrich calls the Contract with America.

The letter goes, dear Mr. Gingrich, as a citizen of Georgia, presumably, I should first congratulate you on your election to Speaker of the House. This is an extraordinary opportunity for you to increase the quality of justice and fairness for all Americans. At the same time, it also provides you with the opportunity to further polarized our nation, to make us meaner than we've ever been before, and to disregard the plight of the weak and the poor who do not have political clout. It is within your power to make our nation either more fair than it's ever been in recent decades, or to make it more mean. Particularly upon the powerless victims of our nation.

You can exalt us to become a great nation. You can cause us to become an increasingly divisive nation. And thus, I read every page of your Contract with America by you and representative Dick Armey-- who does not always speak well of individuals whom he disagrees with. And what I notice, what's on the back of your book, you seem to say what the issues are.

In fact, that's the word you use. Among the pressing issues addressed in this important book are balancing the budget, stopping crime, reforming welfare, reinforcing families, enhancing fairness for seniors, strengthening national defense, cutting government regulation, promoting legal reform, considering term limits, reducing taxes. And I went through every page of your book. And let me make it perfectly clear, I'm against crime, and I favor fair law enforcement, and I favor the work ethic. For our people gave to this country two centuries of labor without a paycheck. And we have worked-- most of us-- whenever we could find it to make the world brighter for the future.

And I recognize that there may be some abuses of welfare. And that to the extent, that those abuses can be eliminated. I favor that.

But what scared me so much is I looked at all of the issues which you said that were important in this so-called Contract with America. Not once do you say that you want to eradicate racial discrimination. Not once did you say that you want to eradicate gender discrimination. Not once do you say that we recognize that when Thomas Jefferson said we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal and they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, and among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, not once do you say Jefferson made the pledge, and he failed.

Because when he said men, he meant all men. Not women. When he said men, he meant men, not women. But when he said men, he did not include those who were black.

And therefore, I wanted to see with your reference to all of the historic figures, that you would have in all of those chapters just one which said that you are for a fair society for the powerless. And the only time you use fairness in your entire table of contents is fairness for senior citizens. That disturbs me.

It's not that I want unfairness for senior citizens, but you talk in terms of the good old days. Now, Newt, you know you and I are both from Georgia. And I've got to figure out when were these good old days about which you speak.

I'd suggest that you go and read a case called Cummings versus Richmond County, Georgia. And in 1899, that county closed up the only black high school in the county because it said that if it spent the money for the kids in a high school, it wouldn't be able to put on a budget for 400 elementary school kids to get an education. You funded high school for all white girls, and you subsidize a high school for white boys. But in Georgia, the state was willing to eliminate educational opportunities. And it wasn't until the late 1920s in the whole state of Georgia that there was one public high school open for colored people.

And I would have felt so much better if you had spoken, recognizing something about the corridor of history. And saying that you stood firm in condemnation of those abuses, and that the federal resources should be utilized to stop it from perpetuate-- from being continued. Now, I know, Newt, you have never had to be denied service at a Woolworth five and $0.10 store when you went in to get a hot dog or a bottle of Coke. But for hundreds of thousands of black people throughout our land-- and particularly in the South-- they couldn't even get a hot dog and a bottle of soda if they wanted to sit at the counter at these lunch counters throughout.

I would think that you would be concerned about that. And knowing this history, that you would be willing to make it clear where you stood. Now, maybe you say that I'm getting too anxious. Maybe you say that I don't know what happened.

And America, what I know is that when we were marching to get access to public accommodation and the sheriff dogs were biting us, and sheriff's hoses were being put on us, George Bush in 1964 said he was against the Civil Rights Act. And Ronald Reagan in '64 and said he was against the Civil Rights Act. And Strom Thurmond said he was against the Civil Rights Act, all claiming that it was unconstitutional.

Therefore does your contract mean to turn back to America to the world which Thurmond, and Bush, and Reagan wanted in 1964? You never had to march from Selma to Montgomery to make a poignant plea that all citizens should be protected by the 15th Amendment, and should have the right to vote. And what I want to do is to ask you, where does your contract stand?

And what was so fascinating to me was that as you talked about enhancing fairness for seniors, I saw nothing about enhancing fairness for children. And let's look at the record. A higher proportion of babies are born at low birth weight in the United States than in 31 other countries, including Romania, Greece, Turkey, and Portugal. The United States ranks 19th among developed countries for infant mortality rates. The United States ranks 17th among all nations in the percentage of one-year-olds who are fully immunized against polio.

We're only 17th. We're behind Romania, Albania, Greece, North Korea, and Pakistan. And in some American cities, between 10 to 42% of the children starting school have not received critical immunization. on time. And I'm reading from government data which no one challenges. And our polio immunization for children of color ranks just 70th in the world.

This country, where the polio vaccine was discovered where the great pharmaceutical companies distribute it, where we brag about having some of the finest research physicians in the world, and we are 70th in the world. I'm frightened by your contract, Newt. But let me point out a couple other facts to you.

I'm for the work ethic. But what is your answer for the fact that the number of people living in poverty was reported last year to have risen to 14.7% of the entire population? A rise for the third straight year. What is your answer to the poverty rate among African-Americans was 33%, and for Hispanics, over 29%? And what is your response to the fact that one of four American children live in poverty?

Aren't those 25% of our kids entitled to at least a page in your book about fairness for children? In the third quarter of last year, the national unemployment rate was approximately 6.6%. But for African-Americans, 12.6%. According to the National Urban League, because of the total underemployment, that it was probably 13% unemployment, to 23% unemployment. Where is the contract of America going to give us some solace?

I hope that you will read Barbra Streisand's extraordinary and brilliant speech given at the Kennedy School last week. We are-- we've got a fine communication system up here in Heaven. We pick up all of the shows and all of the documentaries.

And this is what she said, we are all normal Americans with our problems and complexities, including people in my community. This notion of normal America has a horrible historical echo. It presupposes that there are abnormal Americans who are responsible for all that is wrong. The new scapegoats are members of what Gingrich calls the counterculture McGovernicks.

She concludes, I did concerts for George McGovern in 1972, and I still think that he would have made a better president than Richard Nixon. I'm disappointed that I've read so little in defense of McGovern. Was McGovern countercultural? The son of a Republican Methodist minister, has been married to the same woman for 51 years, and flew 35 combat missions in World War II. Isn't it odd that his patriotism be disputed by a person who never served in the military? And his own family history can hardly be called exemplary.

These are tough words, Mr. Speaker. But yet, I think they have great relevance. Black people are scared, profoundly scared when you talk about Contract with America.

Because there were contracts which caused us to come over and slave ships. There were contracts which caused mothers to lose their children at slave auctions as masters sold kids, where a mother would never see her child. And these sales of human beings were contracts, and were legitimized.

So therefore, Mr. Speaker, what I really hope is that you understand the words equity. That you have a feel for justice. So that those who are weak, and those who are poor, that those who have no political constituency can be the beneficiaries of America's extraordinary resources.

And I don't know whether, Mr. Speaker, I can reach you. And maybe I can't. You've got a successful formula. You've got more white males voting for you than ever. Somehow or another, they seem to feel that they're being cut out.

But I think to some extent, what I would hope that those people who say they believed in my dream, that they would remember the extraordinary message which Rabbi Prinz gave as he spoke at the March on Washington in 1963. He said, when I was the Rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin under the Hitler regime, I learned many things. The most important thing that I learned in my life under tragic circumstances is that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problem.

The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful, and the most tragic problem is silence. A great people which had created a great civilization had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hatred. They remained silent in the face of brutality. They remained silent in the face of mass murder.

And I hope that in our country, that the vast majority of the American people will not remain silent. Will not think that through some magic wand, you can disregard these incredible health figures, or this incredible unemployment, and this destruction of family. And if I could pass on one final message to you, Mr. Speaker. Forget about your contract. Forget about the political rhetoric, which will make you even more successful.

George Wallace did well when he said segregation now, and segregation forever. And he kept getting larger, and larger, and larger votes. And then shortly before his death, he was asked-- then in a wheelchair, then in pain-- said, you stood in front of the door condemning the President of the United States because he was enforcing a decree of the United States Supreme Court to let one black woman-- Autherine Lucy-- get into the Alabama school.

You called it tyranny that the Supreme Court was imposing. And you pledged that you would change conditions at the White House. And now Mr. Wallace, if you had to do it over again, do you think you should have done it?

And his answer was no. Autherine Lucy should have been accepted the University of Alabama. It should not have been necessary to call out thousands of troops there, or in Arkansas, Little Rock, or in Oxford, Mississippi. So therefore, Mr. Speaker, I beg of you to not think about that which will be most politically effective. Because you can probably win that way, and leave the country torn asunder.

And what I would ask of you is to understand that great poet, Langston Hughes, who said, there's a dream in the land with its back against the wall. By muddled names and strange sometimes the dream is called. There are those who claim this dream for theirs alone, a sin for which we know they must return.

Unless shared in common like sunlight and like air, the dream will die for lack of substance anywhere. The dream knows no frontier teeth or tongue. The dream, no class or race.

The dream cannot be kept secure in any one locked place. This dream today embattled with its back against the wall. To save the dream for one, it must be saved for all.

[APPLAUSE]

LAWRENCE: Thank you, Judge Higginbotham Jr. I appreciate you sharing your wisdom, and I admire your courage for sharing your clear vision. Thank you.

I'd like to take this time to make the following announcements. Immediately following this program in the Kresge Lobby, there will be a reception for Judge Higginbotham Jr. And of course, all are invited to attend.

Other Dr. Martin Luther King activities include a free jazz concert, which will be here on Saturday at 8:00 PM, given by [INAUDIBLE] and Associates It is at 8:00 PM, it's free, and it's open to all the members of the MIT community and the surrounding area. Also, professor Melvin King and a community Fellows program will be sponsoring a youth program throughout the weekend. To close our program, Ms. Marion Rosenblum will give the benediction.

ROSENBLUM: We have gathered together today to invoke the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. As we say in Hebrew, [HEBREW], may his memory be an everlasting blessing in our lives now, and forever. At this moment, we appeal to the Holy One of Being with our heartfelt prayers that God may guide us in our strivings to fashion all God's children with minds that seek truth and justice, with hearts that yearn for love and beauty, with voices and bodies that promote equality and acceptance.

May we display charity and understanding to our fellow human beings, whose beliefs and forms of expression may be different than ours. Widen the expanses of our hearts, that we may come to realize the same joy envisioned by King David in the Bible when he said-- and I read first in Hebrew-- [SPEAKING HEBREW]. Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brothers and sisters to dwell together in peace.

[APPLAUSE]