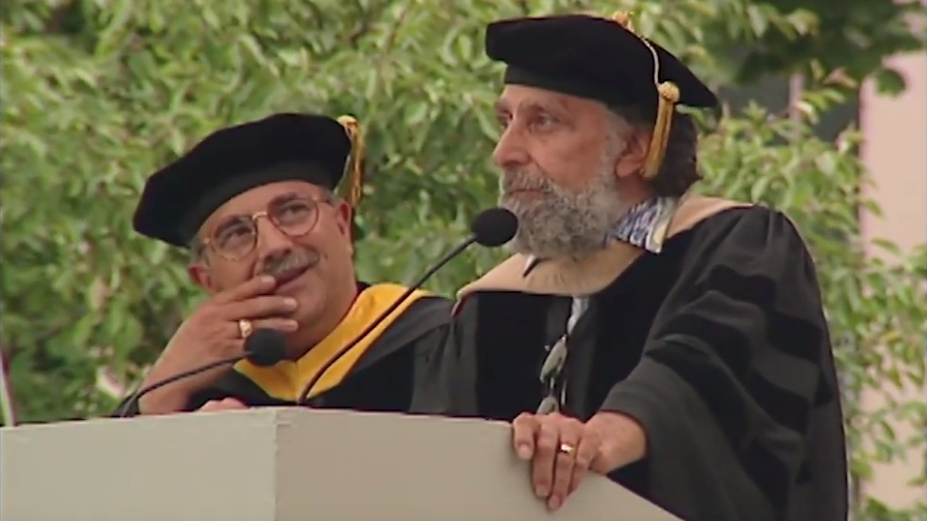

19th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration - William H. Gray III, “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?”

[MUSIC PLAYING]

NICHOLS: Good afternoon.

AUDIENCE: Good afternoon.

AUDIENCE: Good afternoon.

NICHOLS: I am Barbara Nichols, class of 1994, currently majoring in material science and engineering. On behalf of President Charles Vest, the planning committee of the Martin Luther King Celebration, and the MIT community, I welcome our distinguished guest, Reverend William H. Gray III, a native of my hometown Philadelphia, and all other guests to the 19th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Celebration.

This year's theme is the title of Dr. King's last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? This phrase best describes the predicament we are faced with today.

In the '90s, we have witnessed the fall of affirmative action, the explosion of racial tension in our community, the travesty of justice during the Rodney King verdict, and the further decline of our communities. The strides made by the Civil Rights Movement seem to be outweighed by the very infrastructure it had once overcome. For however few who feel the dream is alive, there are dozens more who feel the dream is is dead.

This year's celebration is not focused on Dr. King's dream, but centered upon his ability to empower people for positive change, the revolution for equality for all people. In his last book, he addresses us on how to promote real change in our society. Civil rights legislation is not the end, but it's the beginning for true racial harmony to exist in our society. Now we will open our ceremony with the invocation given by Reverend Scott Paradise.

[APPLAUSE]

PARADISE: Let us pray. Oh God, we need all the grace and strength and courage you can give us. We also know that you have little patience with pretense, and value above all those who are true of heart.

As we honor your servant Martin Luther King today, may we commit ourselves to the full range of his message. He stood for racial justice. He called for a nation where people would be judged by the quality of their souls. May we honor that dream by our actions in this community.

He stood for economic justice. He called for a nation where none would need to be without food or shelter or education or health care or dignity. May we honor that vision in our priorities.

He stood for peace and nonviolence. He faced bigotry and police violence. With prayer, the word of truth, and willingness to suffer, he declared this nation the greatest purveyor of violence in the world. He lost the support of friends and allies by insisting the Vietnam War was wrong. May we honor his memory by calling for nonviolence in our national policy, in our streets, in our homes, and in our hearts.

Give us the spirit to be serious about these things, the grace to be genuine. Give us the courage to give ourselves to the cause of racial justice, economic justice, and nonviolence, that we may have community and not chaos. Amen.

AUDIENCE: Amen.

NICHOLS: At this time, the MIT Gospel Choir will lead us and lift every voice and sing. You'll find the words to the song printed on the back of the program.

[CHEER]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

CHOIR: (SINGING) Lift every voice and sing till Earth and Heaven ring, ring with the harmonies of liberty. Let our rejoicing rise high as the listening skies. Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us. Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us. Facing the rising sun of our new day begun. Let us march on till victory is won.

Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod. Felt in the days when hope unborn had died. Yet with a steady beat, have not our weary feet. Come to the place for which our fathers sighed.

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered. We have come, trading a path through the blood of the slaughtered. Out from the gloomy past till now we stand at last. Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears, thou who hast brought is thus far on the way. Thou who hast by thy might let us into the light, keep us forever in the path we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we meet met thee. Lest our hearts, drunk with the wine of the world, we forget thee. Shadowed beneath thy hand may we forever stand true to our God, true to our native land.

[APPLAUSE]

NICHOLS: There's a slight change in our program. At this time, there will be a dance selection performed by Robin Offley from the Admissions Office. Well, right now we'll just move on in the program.

[LAUGHTER]

It has been the tradition of the Martin Luther King Celebration to hear the youth perspective on the life and legacy of Dr. King. First we will hear from two Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School students. They are [? Myesha ?] Simmons and Adeline Rodine.

[APPLAUSE]

SIMMONS: To President Vest, to our esteemed guest speaker, to the other members of today's program, and to you, our audience, I bid you a fond good afternoon. It is indeed a privilege and an honor to come before you to commemorate the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Given the theme of this year's program, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, I would like to share with you some of Dr. King's thoughts on this question, excerpt from his address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. "I want to say to you, as we talk about where do we go from here, that we honestly face the fact that the movement must adjust itself to the question of restructuring the whole of the United States.

There are 40 million poor people here, and one day we must ask the question, why are there 40 million poor people in America? And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising questions about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy. And I'm simply saying that more and more, we've got to begin to ask questions about the whole society.

We are called upon to help the discouraged beggars in life's marketplace, but one day, we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring. It means that questions must be raised.

You see, my friends, when you deal with this, you begin to ask the question, who owns the oil? You begin to ask the question, who owns the ore? You begin to ask the question, why is it that people have to pay water bills in America, in the world, that are 2/3 water? These are questions that must be asked.

Now when I say question the whole society, it means ultimately coming to see that the problem of racism, the problem of economic exploitation, and the problem of war are all tied together. These are the triple evils that are interrelated. A nation that will keep people in slavery for 244 years will thingify them, make them things. Therefore, they will exploit them, and poor people generally, economically.

A nation that will exploit economically will have to have foreign investments in everything else. and will have to use its military might to protect them. All of these problems are tied together. And what I am saying is that we must go from this convention saying, America, you must be born again.

Let us realize that William Cullen Bryant is right. 'Truth crushed to the Earth will rise again.' Let us go out realizing that the Bible is right. 'Be not deceived. God is not mocked. Whatsoever a man soweth that shall he also reap.'

This is for hope for the future. And with this faith, we'll be able to sing in not some distant tomorrow, with a cosmic past tense, we have overcome. We have overcome. Deep in my heart, I did believe we would overcome." Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

RODINE: Good afternoon.

AUDIENCE: Good afternoon.

RODINE: My name is Adeline Rodine. I'm a student in the MIT/Wellesley Upward Bound Program and a senior at the Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School.

Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. is my leader, and hopefully your leader. He was a man who believed in something and carried his belief to its fullest extent. He was a civil rights leader. He had a dream which he fought for. He did not just sit down and say, I have a dream, without doing anything about it like a lot of us do.

Instead, he fought for the rights of our people. He fought so that not only black but all people would be treated equally. Because of the efforts of Martin Luther King Jr. and many other civil rights leaders, blacks and other people of color are now allowed to sit anywhere on the buses, drink from the same water fountains, eat in the same restaurants, and attend the same schools as white people.

Martin Luther King Jr. should not be remembered on January 15 just because of his birthday, or in February just because of Black History Month. No. A man of his stature should be remembered throughout the year by everybody. We should all work to keep a peace of Martin Luther King Jr. within us such that his life and beliefs will inspire us to live better and more prosperous lives.

Although Martin Luther King died almost 25 years ago, his spirit is still alive for all of us here today. If we just adopt his beliefs, we can continue his work. I say let's start by stopping discrimination. Let's stop the black on black crime. Let's stop the hatred and killing.

Some of us are allowing prejudice and bigotry to enter into our dealings with one another, while others of us are saying, I love Martin Luther King, yet finding it possible to take another's life how can we be believers of Martin Luther King, and at the same time, practice that which he was so strongly against. I would like to leave you with that thought as you reflect upon the theme of today's program. Where do we go from here? Chaos or community? Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

NICHOLS: Next we will hear from two MIT students. There has been another slight change to the program. First, [? Myesha ?] [? Richards, ?] class of 1995, will give her reflections. Then Adam Morales, class of 1996, will speak in place of Melissa Gonzalez.

[APPLAUSE]

PRESENTER: Good afternoon. My name is [? Myesha ?] [? Richard, ?] and I'm a sophomore here at MIT. I would like to take some time today to reflect on today's subject, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?

I would like to advance towards community, working with my neighbors of all races to achieve a more peaceful world. I would also like to advance the community of my people so we continue to be a strong, proud race.

So you may ask, how do I believe we should achieve this community? I believe that first we must educate ourselves. I have the highest respect for those who return to formal education after a severe break. Those who obtain GEDs after dropping out of high school or degrees after establishing a family should be commended by everyone.

[APPLAUSE]

The thought of raising a family and continuing a career and attending night classes amazes me. Even if you don't go to formal school, attend company seminars and training classes. Educate yourself with common sense by paying attention to your surroundings at work and in the community. Pay attention to others' attitudes about you, and do not associate with those that tear you down.

Secondly, we must remember those less fortunate than ourselves. We need to support one another and not tear each other down. If someone tries to take on an impossible task, don't immediately dissuade him or her. Reveal the disadvantages the person may have overlooked. If he or she understands and has considered the problems yet finds the goal obtainable, encourage him or her. The results may be surprising. And if not, support the person when your help or sympathy is needed.

Take time to listen to each other. Don't become so wrapped up in academics or your career that you don't stop for a friendly conversation, for nothing is more refreshing than interaction with fellow man. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

MORALES: Good afternoon. My name is Adam Morales, and I'm a freshman here at MIT. I would like to open with an excerpt from a tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. written by Harry Belafonte and Stanley Levison. "In a nation tenaciously racist, a black man [INAUDIBLE] conscience. In a nation sick with violence, a black man preached nonviolence. In a nation corrosive with alienation, a black man preached love. In a world embroiled in three wars in 20 years, a black man preached peace.

When an assassin's bullet entered Martin Luther King's life, it failed in its purpose. More people heard his message in four days than in the 12 years of his preaching. His voice was still, but his message ran clamorously around the globe."

Martin Luther King's message was meant not just for blacks, but for all suppressed people. His words affected my life greatly as a young Puerto Rican growing up in Brooklyn.

I have faced discrimination in many forms. I have had teachers accuse me of cheating on tests because there was no way possibly of me doing it well on my own. Classmates have asked me before if I had ever been in jail, and many have kept their distance. Even when I was accepted to MIT, many told me it was just because I was Puerto Rican.

Martin Luther King had a dream, a dream in which all people, regardless of color or nationality, would be equal and at peace with each other. I've grown up believing in this dream. I've worked hard to overcome the stereotypes placed on Puerto Ricans. I've shown them I am just as smart as anyone else, and deserve to be treated equally, not inferiorly.

I still look forward to the day when I can be recognized for who I am and what I've done. I can't predict the future, but I know how I will approach it. I will work toward the dream of Martin Luther King, a dream where all people can come together in a community, not separated by our differences, but brought together by our similarities. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

NICHOLS: Now we will see a dance selection performed by members of the MIT dance troupe Movements In Time.

[MUSIC- THE WINANS, "MILLIONS"]

THE WINANS: (SINGING) If I can just make it up there, and if I can walk through that city bright and fair, there'd probably be a thousand things I want to tell the Lord on that day, on that day, that day, ooh. I'll just begin to cry. You'll wipe the tears from my eyes. I'll say thanks. You'll ask why. This will be my reply.

You know millions didn't make it, but I was one of the ones who did. I'd look at God and say, millions didn't make it, but I was one of the ones who did. Yeah, don't you know, there would probably be a thousand things that I, I'm going to tell the Lord, talk to the Lord on that day. On that day.

Oh, yeah. I'll just begin to cry. You'll wipe the tears from my eyes. I'll say thanks, you'll ask why. This will be my reply. You know that millions didn't make it, but I was one of the ones who did. I'll tell everybody, millions didn't make it. Yeah, b but I was one of the ones who did. I'll tell everybody, millions didn't make it, but I was one of the ones who did.

You see, I made it over. I came through hard trials and tribulations, persecutions, I was one of the ones who did. Millions didn't make it, but I was one of the ones who did. I'm so sad to tell you, millions didn't make it, but I'm mighty glad to let you know, I'm one of the ones who did. Millions didn't make it, but I was one of the ones.

You see, I made it over. I came through great trials and tribulations. I was one of the ones who did. I made it over. I had folks that didn't believe I would make it, but I want to testify that I made it over. I made it over. [INAUDIBLE] no man could number. And I was in that number. I made it over. I made it over. Look at me, walking streets of gold in the land [INAUDIBLE]. I made it over. I made it over.

[APPLAUSE]

NICHOLS: Now President Vest will give us his opening remarks and introduce our keynote speaker.

[APPLAUSE]

VEST: Thank you, Barbara. On behalf of MIT, it is my great pleasure to welcome all of you to this assembly in honor of and in celebration of the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Before we begin the formal part of the program, I would like to take a moment to honor another person who has made a great difference to the life of MIT and to working men and women throughout the country. I refer to our colleague, professor emerita Phyllis A. Wallace, who died earlier this week.

A member of the Sloan School faculty, Professor Wallace was a labor economist who pioneered the study of racial and sexual discrimination in the workplace. In the early 1970s, she directed studies for a landmark federal lawsuit on discrimination that had far-reaching consequences for the wages and working conditions of women and minorities nationally. It was our good fortune when she joined the MIT faculty in 1975, bringing these same interests and expertise into the research programs and curricula of the Sloan School.

Even after her retirement, she continued to serve MIT in significant ways, and recently had begun to work with Dean Lester Thurow on special projects that required Phyllis' wisdom, diplomacy, and effectiveness. And it was my own good fortune to meet Professor Wallace as a member of the Presidential Search Committee that brought me to the Institute. I had that even greater privilege thereafter of calling on her wise advice on how to move MIT's diversity agenda forward. We will all miss her greatly.

This morning, I would like to comment on the theme of this year's observance taken from Dr. King's last book, Chaos or Community? Where Do We Go From Here? The term chaos has more than one meaning. One meaning indeed is particularly fitting for us at this Institute of Science and Technology. That has to do with the new science known as chaos theory, which was pioneered by Ed Lorenz, a professor in our Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences.

This new science of chaos deals with nonlinear and irreversible events, best known, of course, as the butterfly effect, where a small disturbance becomes nonlinearly amplified to generate major change. This means that literally the beating of a small butterfly's wings can initiate a change of atmospheric motions that ultimately become a giant storm.

One might say that Martin Luther King Jr. Demonstrated this effect in the social and political realm. For if ever one man's life and one man's life work changed an entire society irreversibly, it was his.

But this is the difference between human and physical environments. Unlike the particles that make up our atmosphere, we are not passive. We can participate. We can think. We can act. We can grow. This is what gives us hope, because it is our ability to act with mutual purpose and to grow together that will enable us to avoid the usual meaning of chaos, which is the absence of harmony, a state of utter confusion, a total lack of order.

What we need as never before is a sense of community, a sense of common purpose. The matter of community is very important to me. In my remarks at the first Martin Luther King convocation that I attended as a member of the MIT community, I talked about celebrating both our individual differences and our common humanity, but also about refusing to let the centrifugal forces of intolerance and injustice pull us apart.

These are the forces that can create chaos out of community. They pose a clear and present danger. I understand and I encourage the different groups within our community to have and to celebrate a strong sense of identity and culture, but I also sense a danger in increasingly defining ourselves entirely by our racial and ethnic origin.

Yet Andrew Hacker's recent book Two Nations makes abundantly clear that through the kind of hard statistical data that we tend to value at MIT, that we, black and white, are indeed inhabiting two different worlds to a far greater degree than most of us would like to admit. We must be proud of who we are, interested in where we have come from, and we must celebrate and understand our differences.

But this will all be for naught if we fail to see the greater glory in our common humanity, or the greater purposes to which we can apply our varied talents and perspectives. We must build on our differences, but we must build toward a common purpose.

Nowhere should community be so important as in a university where we gather for the common purpose of learning. Despite the frailties and faults of the society around us, we can and must do better in order to achieve the common purpose that has brought us here together in Cambridge.

During this last term, I visited two classes here at MIT to talk with students about the culture and climate of the Institute. Members of Professor Mel King's class on peace, justice, and planning spoke to me of the issue of community in a statement that they had prepared to describe their view of the mission of MIT.

Their vision of our mission said in part, and I quote, "MIT is committed to fostering a community which expresses the variations and culture of the people of the world, and which is enriched by a dialogue among the people of our community. Leaders in society must be able to interact on a global level with people from varied backgrounds. Leadership in the global community requires recognition of our common needs and the spirit of cooperation of work toward meeting those needs." Surely, that vision of these students is one that we can all share.

Before I visited Professor Robin Kilson's class on black studies, I was privileged to read several of the essays that her students had written on the subject of racism at MIT. They were so interesting and insightful that I also asked for permission to share them with the members of our academic council.

It was of some comfort to me, I suppose, to learn that these students find the same tensions, incongruities, and frustrations that I do in trying to understand and improve the racial climate on our campus. The dozen or so students whose essays I read clearly inhabited a dozen or so distinctly different MITs. In the end, I concluded that the primary differences among these students stemmed as much from how they defined themselves and their own levels of tolerance as from the definitions bestowed by our community and the intolerance about them.

But clearly, we all have a lot of work to do to reach the vision expressed by the students in Professor Mel King's class. What will it take? One thing obvious but not simple is to see that the population of MIT represents the best in creativity and talent from all segments of our nation, and that everyone has the full opportunity for academic and career achievement once they are here.

Let me say flat out that we have not done well on the faculty front in the past several years. Only 3% of our faculties are underrepresented minorities. But of the faculty appointments made last year, almost 7% were members of underrepresented groups. Last year was the first year of a new program to recruit minority and women faculty to our campus, and the provost and I have been working to see how that program can be made ever more effective.

This fall, the task force on minority administrators pointed out problems in career advancement, noting that fewer than 100 members of our administrative staff are underrepresented minorities, that very few are in the highest levels of management. We are now working to implement many of the recommendations from that task force, which for the first time systematically analyzed career patterns of different groups within the Institute over time.

On the undergraduate front, we have much more to be pleased about. Underrepresented minorities now comprise 15% of our student body compared with 8% in 1980. We are concerned about a drop in this year's freshman class, however, and we will be monitoring the situation carefully during the coming year.

At the graduate level, however, we are stuck at the dismal level of 3% during this entire period, although we had an increase of 50 in the number of new graduate students of African American, Hispanic American, and Native American heritage this year. This may not seem like a large number, but when you consider that it is a 21% increase in a single year, it represents a sea change. This dramatic improvement is a result of aggressive activity on the part of the Office of the Dean of the Graduate school with a lot of help from individual faculty and students, and it is an area which we must and will continue to emphasize.

Now I know that numbers are not the whole story, nor are they the answer in and of themselves. But I am trying to keep the facts in front of us, because ultimately, the students that graduate here are the most important measure of our effectiveness in improving both the opportunity for and the quality of education in this nation.

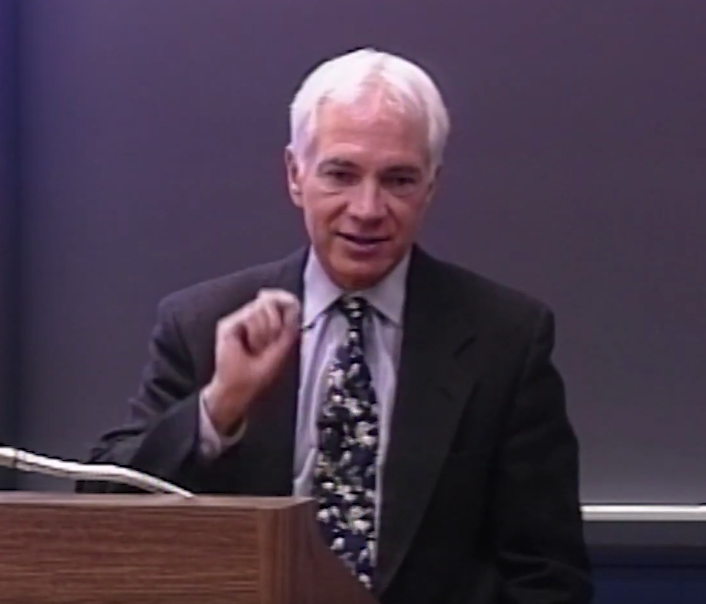

It is now my privilege to introduce today's speaker, William H Gray III. If anyone can speak to the question of how to improve educational opportunity and experience in our society, it is he. Like Dr. King, Mr. Gray comes from a family of ministers and teachers. He himself has been in the ministry for nearly three decades, and has been the pastor of the 5,000-member Bright Hope Baptist Church in Philadelphia for more than 20 years, as was his father and as was his grandfather before him.

But it is as a legislator and an educator Mr. Gray is best known. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1978, and became the first black member of Congress to hold the position of Majority Whip. He left his mark on our Congress and our country in many ways. He played a key role in implementing economic sanctions against South Africa.

As Budget Committee Chairman for four years, he earned a reputation as a consensus builder between the White House and the Congress in budget negotiations. And he was an effective leader and advocate for the historically black colleges and universities of this country.

His support of education and the position that he holds today as President and Chief Executive Officer of the United Negro College Fund flow naturally from a family tradition of leadership and education. His father was the president of two black colleges. His mother was a college dean. His grandfather was a college professor, as is his sister.

Reverend Gray has proved a worthy heir to this legacy. Not only has he served on the faculties of several colleges himself, he has since 1991 headed America's oldest and most successful fundraising organization on behalf of African American students.

I don't have to tell you that that this is a critical time in history for our black colleges and universities. African American high school completion rates and college enrollment have reached all-time highs.

And the challenge, as Reverend Gray himself has put it, is to prepare record numbers of African Americans for successful careers in every imaginable field. To that end, the fund, in addition to its traditional forms of support, is establishing an institute to coordinate research on issues related to African American education at every level, from preschool to graduate study.

Obviously, I could go on regarding his career, but I'm sure you've heard enough from me, and are more than ready to hear from the man who honors us with his presence today. Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. William H. Gray III.

[APPLAUSE]

GRAY: To President Vest, to Barbara Nichols, whose father and I were Boy Scouts together back in Philadelphia, in North Philadelphia, to the faculty and students and fellow participants here at this MIT celebration as you come together to remember a spiritual giant, Martin Luther King Jr., I am delighted to join you as you pause to remember and to reflect upon Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?

When you came into this auditorium today, you saw a film, a film that went back nearly three decades ago to that great day when over a quarter of a million Americans gathered at the Lincoln Monument to hear the dreamer's dream. I was there. I was there standing under a tree, because there was no room around the reflecting pool. I was there along with all of the others in the 90-degree heat in August as people of all creeds, all colors came together to protest American apartheid.

I was there as I heard Peter, Paul, and Mary sing the hymns of the service. I was there when the great Mahalia Jackson gave the meditation. I was there when Martin Luther King went to the microphone to speak. There was a silence that was unbelievable, considering that we were outside and there was over a quarter of a million people.

And I stood under a tree almost a quarter of a mile away from the steps, But yet you could hear the leaves rustling in the wind as everyone strained to hear the speaker, Martin Luther King.

For Martin Luther King symbolized a great movement, a nonviolent movement, a revolution that took a country and changed its basic political, social, and economic institutions. Martin Luther King symbolized a movement that was destined to change this country forever, and we listened as he told us about the importance of that day.

Now for most of you, you have seen on television many African Americans speaking to large crowds. You saw Jesse Jackson in '84, running for president, addressing the nation at the Democratic National Convention. You saw him speak on many occasions. You've seen legislators and mayors. David Dinkins, people like Doug Wilder. Yes, you even used to see a guy named Bill Gray from North Philadelphia debating fiscal and economic policy.

You have grown used to the fact that you can see people of color being on center stage. But to understand that moment in 1963, you must try to remember what America was like. And in order for us to know, where do we go from here in 1993, you have to understand what 1963 was about. For most of you in this room were not even born then, and Martin Luther King Jr. Is simply a celluloid image that you see on television, or perhaps you read about in a book.

But let me tell you about that day and about the America of that day. This was the first time any African American ever stood on a national stage and spoke to the entire nation through the electronic medium called television. This was the first time that blacks and whites had come together in many decades to protest American apartheid.

For what was America like? It was a country where we had passed into law apartheid. Yes, America was a country where blacks could not go to Duke University, even if they could play basketball. Blacks could not go to the University of Alabama, even if they could run the 40-yard dash with a football uniform on in 4.1 seconds.

[WHISTLE]

Blacks could not go to Georgia Tech to get a college degree. As a matter of fact, they could not even ride on public transportation except in those places reserved for people of color. And when the bus began to fill up and whites got on the bus, the law required that blacks get up-- men, women, and children-- and give their seats to those who were white.

America then was not the America you know today. In those days, this was not a phenomenon simply in the South, in Georgia and Mississippi, even though that was the target of the Civil Rights Movement.

But oh, yes. The virtuous North was not so virtuous. Here in Beantown, you did not have blacks serving in capacities that ordinary citizens served in. The police force, the fire department, having the opportunity to elect officials.

And yes, even in Boston, blacks could not live where they wanted to live, even though they had the money, and there was a ghetto for them. It was called Roxborough, I believe, just like it was Harlem in New York, like it was North Philadelphia in Philadelphia, like it was Watts in Los Angeles. That was the America of then.

And something changed. What happened was a spokesman was found to articulate the aspiration of those who had been oppressed simply because of the color of their skin. And there were no voices back then who were talking about meritocracies. There were no voices back then who were calling for a level playing field, who now today often quote Martin.

Back in those days, you could not travel from Boston down to Georgia without having in Washington, DC to move to the segregated cars of the train in order to sit there. Oh, no. You couldn't stay in the Sheraton, the Hilton, or the Holiday Inn if you were black. That was America.

But one man came along, simply because a black woman in Montgomery, Alabama decided one day in the 1950s that she was tired of getting up and giving her seat to white folk simply because of the color of their skin. And she refused to get up, and they took her off the bus and locked her up and mobilized that community to protest, and they looked for a spokesmen.

And there was a new minister in town, a minister who had come from a family of ministers. A minister who had come from a family of people who had fought injustice. A father and a mother who had been successful but who fought injustice.

A minister who had gone to a little black college in Atlanta, Georgia, because in those days, blacks couldn't go to most white colleges. And even those that they could go to didn't want too many of them around. And so he went to Morehouse, but he just graduated and gotten a PhD up here in Boston. And he was the minister of a historic church.

And they said, let's go and call on Reverend King, and he became the spokesman for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. And from that was formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And from that, there was a movement of marching feet, of people sitting in, praying in, swimming in, just confronting racism and segregation and apartheid all across this land until that day in 1963 when they all came together.

And by 1965, the walls had come tumbling down. The pattering feet of Joshua's army had brought down segregation in America without a shot being fired, without a political revolution. A nonviolent movement passed the Civil Rights Bill of '64 and the Voting Rights Bill.

Because you see, blacks couldn't vote in America just 30 years ago, despite the fact that they served in every war and died for this country going back to Crispus Attucks right here in Boston. And thus, by 1965, the walls had come tumbling down.

And then the movement started to change. It was no longer a civil rights movement changing the law to allow people to have the rights of everyone else. It moved to an economic and political rights movement, and Martin Luther King became the spokesperson as he started organizing across America. not just in the South, but also in the North as he tried to put people together to go out and vote, and also to call for economic justice.

Most people forget Martin Luther King Jr. was not killed in a civil rights march. Oh, no. He was killed in an economics rights march. He was not killed fighting simply for black people. Oh, no. He was fighting for fair wages for all the sanitation workers in that city in Tennessee. And he had taken the cross from the altar and placed it between two garbage cans in Memphis, calling for a new economic and political order not just for black Americans, but also for all Americans.

And before he died, and before that assassin's bullet killed him, he wrote a book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? He said our choice is to go back to polarization, conflict, hatred, intolerance, strife, or our choice is to become a community.

Well, it's 30 years later, my brothers and sisters. Where are we today? First, I think Martin Luther King Jr. would say we've come a mighty long way. Because today, you can look around and you can see the changes that are wrought.

This year as we start a new administration in Washington, DC, there will be 40 members of the Congressional Black Caucus, three of them coming from the state of Florida, three of them coming from North Carolina, the very places where Martin had called for a new political order. There's a bright side to the story.

And when we look, we see people like Doug Wilder who went to a little black college called Virginia Union who is now the governor of the state of Virginia, a state that just 30 years ago would not allow Doug Wilder to go to the University of Virginia. And now today, we can see people like David Dinkins as the mayor of America's largest city, despite the fact that African Americans do not make up the majority of that city.

We not only see progress in politics, but we also see it in other fields. No one has to tell you that when you turn on the television, not only do you see people like Michael Jordan, but you also see Oprah Winfrey, who has moved Phil Donahue right off the scale.

[LAUGHTER]

[APPLAUSE]

And now you can see not only beyond sports entertainment, but you see people like Reginald Lewis, who is the Chair of a multibillion dollar corporation Beatrice. And you see people like Bill Cosby who has become an entertainment and communication conglomerate himself, and is now talking about buying NBC. We've come a mighty long way.

[APPLAUSE]

And yes, I know we've come a mighty long way when I come to MIT and look around at this audience and at this campus. For you see, when I was going to college, there were hardly any of my kind who were either students or faculty at this institution. And Lord help, you even got a gospel choir.

[LAUGHTER]

[APPLAUSE]

We have come a mighty long way. And I think Martin Luther King would say, yes, we have made some progress toward a sense of community. But on the other hand, I believe that he would caution us not to be too optimistic, not to assume that progress will continue, and not to assume that everything is all right here in our country.

For you see, there's a dark side. We have failed to reach community. There's still chaos in this country. There's still prejudice. There's still racism. There's still bigotry. There's still antisemitism. And Martin Luther King Jr would point that out to you. And it is no longer simply a private matter, for there are those who would have you believe that, yes, we know it's around, but it's really a private matter. No, it is not.

For you see, it is still embedded in the structures of our society. Its economic structures, its political structures, and yes, even its educational structures. There is still racism, antisemitism, and bigotry in our society.

And let me share with you those things that people like to forget about. The fact is last year that the Census department and the Labor Department's reports point out that in 1992, the average black family median income is still only 57% of white family median income in America, exactly where it was in 1968. Martin would say, we haven't made progress yet.

And when you look at the infant mortality rates that exist in some of our inner city and rural areas for poor children, white and black, and understand that we can cure that problem very simply but yet we won't, Martin would say, we still have not made progress yet. And when you look at the fact that even today, though we predominate the basketball court, the football field, whether it is the Bills or the Boston Celtics, we still haven't gotten into the front office of the coaching ranks of those sports. We still have a long way to go.

[APPLAUSE]

And yes, even though we've got Bill Cosby, Oprah Winfrey, and all of those shows on television that are popular and making money and symbolize the problems, the frailties of all American families, the fact is that we still haven't gotten into the boardrooms of entertainment and communications, or at the executive level.

[APPLAUSE]

And yes, Martin would say we still have a long way to go. For despite the fact that we will see in a new administration a lot of women, the reality is that women of all color-- black, white, brown, Asian American, Latinos-- still do not have equal opportunity with white males in American society. We still have a long way to go.

[APPLAUSE]

And Martin would laugh at those who use his name and his quotations incorrectly. Those who stand up and say, didn't Martin Luther King Jr. say that one day he wanted to see his children sitting at the table with other children of other color, other races, and they would be judged on the content of their character and not on the color of their skin? And didn't he mean by that that we should get rid of any attempts to redress nearly 400 years of legalized apartheid in this nation, and only 25 years of some progress?

And therefore, they use Martin's words to call for the elimination of affirmative efforts to integrate faculties, staffs, and diversify student bodies and say, we want a meritocracy, and people ought to be judged on the content of their character. That's what Martin was talking about, wasn't he?

[APPLAUSE]

It is insulting, degrading, and downright wrong. Martin talked about that as a scatological hope, not a reality that could be reached in 25 years. You don't level the playing field in 25 years for minorities and women after 400 years of legalized slavery and dehumanization and then say, everybody is equal.

[APPLAUSE]

Oh no. We won't reach community if we fail to understand what he stood for. And we've seen people today retreating. Some of them even marched with us down there in Washington.

I've seen people suddenly as they are worried about competition from those women and minorities who now in the workforce begin to say, we've gone too far with this affirmative action stuff. We've gone too far allowing these minority students to come in. And I have seen professors and faculty members-- I know y'all are not going invite me back no more--

[LAUGHTER]

[APPLAUSE]

--who 25 years ago were in the forefront of the movement for progressive government and opening up the system now begin to question the capabilities and the qualities of those minorities that we are allowing to come to our great university.

[APPLAUSE]

My Hispanic brother talked about how in his experience today-- and I hope you heard him-- that professors look at him and say, you don't belong here. You got here on a special program.

Well, brother Morales, don't feel bad. I remember when I went to my college. There were five of us in the whole place. And I remember after being accepted and going to look over the campus with my father-- and I was fairly successful.

I was the only four-letter athlete in my high school. I was fourth in a class of 369. I had a 3.75 grade point average in high school. And my SAT scores were pretty good. And I remember the dean of admission sitting there-- I had already been accepted-- looking at me and saying to my father, I really don't think he ought to come here, because he'll never graduate.

And I'll never forget four years later when we had the honors banquet-- God is not mocked. You do reap what you sow. And to put it in another term, as we said in North Philadelphia, what goes around cometh around.

It just so happened that as I sat at that banquet prepared to receive the highest award given to a history major in every senior class, guess who was sitting right next to me? The same man who had told me four years ago that I had no business at that institution. Well, my father looked at him and said, ain't you the dude who said--

[LAUGHTER]

We have become confused, and we have lost sight of what the struggle for the beloved community is. The struggle for the beloved community is to open the doorway wider. The struggle for the beloved community is to build bridges so that those who have been historically disadvantaged will have an opportunity to catch up.

And thus, those who argue today that the playing field is level, those who quote Martin Luther King about the content of their character and the color of their skin, I have one question to ask you, and that is simply this. Are all American women of all colors standing on the same level playing field with white males in America? I think you know the answer to that, and the answer's hell no.

[APPLAUSE]

We've made progress, but don't take a few token deans, a few token professors, a few token achievements in entertainment, and yes, even in politics, and then conclude that we've struggled long enough. Yes, we've come a long way, but we still have an even longer way to go in our society to have community and avoid the chaos that we see on some of our college campuses and some of our communities like in New York with Crown Heights.

Finally, there's one other thing when you talk about where do we go from here. You not only have to know the truth of where we came from. And my brothers and sisters, there are some people who are trying to retell the story about the past. Revisionists, I think they're called in academia, who want to act like things were not that bad.

They were bad. So don't let anybody tell you, let's go back to the good old days. Number one, they weren't good, and they weren't old. They were not that old. They were young.

But the question becomes, if we are in a moment of our history where we've made progress since Martin's book and since 30 years ago when he gave the speech, what must we do now to continue to move toward building community? I will tell you that it is more imperative today than ever before.

And let me tell you why. It has nothing to do with good feelings. It has nothing to do with humanitarian, moralistic motives. In a real sense, the desire to build community today is a much greater imperative than ever before.

And the reason is that there's a revolution going on in America, and most of you are not even aware of it. No it's not the global revolution, geopolitical where you see the walls come tumbling down, the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union and the ethnic centrifugal forces of self-determination redrawing the map of Europe or Nelson Mandela being free in South Africa. That's not it. And it's not even the global economic competitive revolution where we've got competition in the Pacific Rim and in Europe.

No. There is another revolution. Let me quickly describe it for you, because it is an economic imperative for all of our interests to move toward community and opportunity for all God's children.

I saw it the other day when I got on an airplane. I got on-- and I'm fascinated by planes. And they had the door open, and I looked in, and I saw the captain, hair hanging all down the neck. And I said, what happened to rules and regulations? What happened to values? And then the captain turned around. She was a blonde.

[APPLAUSE]

And then I looked over and I saw the first officer, and he was a brother. I said, oh, Lord. Then I looked at the flight engineer, and he was an Asian American. And about that time, someone tapped me on the shoulder. the head flight attendant to tell me I was blocking traffic. And I turned around, and there was Juanita Rodriquez, telling me to go sit down. I said, oh, Lord, I'm in trouble today. But let me tell you, that was the best flight I have ever had in my life. They flew that plane and landed it magnificently.

[APPLAUSE]

But that experience symbolizes at a revolution that is going on right now that is creating an economic imperative for the beloved community. And it's simply this, that in the next century, 85% of all the new workers in America are going to be women, minorities, and new immigrants. And that means that all of us are increasingly going to have to depend upon the productivity, the skills, the excellence of those today that we call disadvantaged.

So it is in our own self-interest to move toward a community of equal opportunity, or else the prosperity, the strength, and the growth of this nation will decline. Why? Because these are the people who are going to be America's future.

And so we must move toward community. And in order to move toward community, there's something that you and I can do. There are four things that I suggest that Martin would want us to do.

First, we have to achieve excellence. Don't sit around here at MIT, sucking your militant thumb because you find out there may be some residues of racism at this university. What did you expect?

[LAUGHTER]

There is no difference between the people here and the people out there. It's just the people out there are working inside here or coming here to go to school. Understand that you are here to achieve excellence and to assimilate all the knowledge, traditions, and information so that you can move forward and build a new world order. Martin Luther King was a strong believer in educational excellence. That's why he had a PhD. He had a master's of divinity and a bachelor of arts degree as well.

And if you are to be catalysts for change, if you are to build a beloved community, I don't care what color you are. I don't care what sex you are. I don't care where you come from. You have got to achieve educational excellence.

So don't get mad and sit around because you find some problems. You ever see Michael Jordan say, time out and walk over to the side and say, coach, every time I get the ball, there are five people trying to stop my stuff?

[LAUGHTER]

You ever see that? You ever see-- what's that brother here with the Boston Celtics? Lewis? You're supposed to leap all over the place. You ever see him say, time out and go over to the coach and say, every time I get the ball, somebody trying to stop my stuff? You ever see Robert Parish do that? No. Why?

Because they know that the moment they get on that field, the moment they get on the court, that's the name of the game. Somebody's out there to stop your stuff. So therefore, understand that you will never achieve success by sitting around, crying about the problem. Run faster, jump higher, and shoot straighter than anybody else.

[APPLAUSE AND CHEERING]

And then you too will be able maybe to sit at the honors banquet and look the director of admissions in the eye and say, aren't you the dude that told me? Secondly, also remember something else. You are put on this universe, on the starship called Earth not just to take care of you or yours. You are put here to be of service to your community and to the human community.

So if all you do is achieve excellence, and then go out and make as much as you can, can as much as you can, and then sit on your can, your name is swine. But if you go out in life, make as much as you can, can as much as you can, and give back as much as you can, then you will be called blessed.

[APPLAUSE]

The reason why we remember Martin Luther King Jr. today is because he didn't sit on his PhD from Boston University. He didn't sit on his master's in divinity from Crozer Theological Seminary. He didn't sit on his MA bachelor's degree from Morehouse, just make money. But he decided to do something for a larger cause, for a larger purpose. You too must be willing to give service.

And then thirdly, you must have within you a sense of brotherhood and sisterhood that overcomes intolerance, bigotry, antisemitism, prejudice, of all kind and sexism. Why? Because they're all sides of the same coin.

And my brothers and sisters, sure, folks going to make you mad. There are going to be people in other communities who will not understand your struggle. There will be people who will make you awfully angry. But if we're going to build the community that is beloved, we must begin the revolution within ourselves of loving one another, tolerating one another, and yes, even when other folks in other communities hurt us, try to sensitize them and bring them to a new position not by violent means or by hating them in return, but by showing them that we are better and we know a better way.

Let me tell you what I'm talking about. I remember one event that will always be framed in my mind about Martin King. If you see, not only was I there in 1963, but the King family and the Gray family have been friends for three generations.

I used to preach at Ebenezer Baptist Church on many occasions. So did my father. And when Martin Luther King Jr. went to Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, he often used to come to our home for meals on the weekend and to practice preaching at the Bright Hope Baptist Church where I am now the pastor.

And I knew Martin first as a young man who was in seminary, and not as a Nobel Prize winner. And I suppose when someone you know ends up being great, a superstar, you know, it's a hard gap. But I will never forget one thing that had happened that proved something to me about brotherhood, sisterhood, tolerance, and love of humanity.

Martin Luther King Jr. was nearly killed in New York. He was stabbed by a woman with a knife that went so deep into his chest they had to take him to the hospital with it still sticking out to perform the surgery to remove it, because it was so close to his heart. And I'll never forget that when Martin recuperated and got well and went back to the South, he decided that he couldn't stay in the South, but he had to come North and raise money.

He came to our home in Philadelphia, because he didn't have the money to stay in hotels. The movement was too poor. And so he stayed with the Grays at 1511 North 16th for a week as he tried to raise money in Philadelphia.

And I'll never forget that every morning and every evening, he would have to put ice on this terrible scar that was still raw on his chest. And of course, all of us would start to talk about the woman. You know, she was no good. We'd start calling her names and all of that.

And I'll never forget to this day that Martin stopped us cold in our tracks and said, don't talk about her that way. No matter what she did and no matter who she is, she's a child of God. And from that moment on, none of us talked about the woman that nearly killed him for the rest of the week, even though he obviously was in pain as he would put ice on this raw scar tissue.

You see, Martin understood that we are all part of a network of mutuality. We are all brothers and sisters, regardless of the color of our skin, regardless of where we live, regardless of where we come from. And it behooves all of us to try to help the rest of us if we are going to have a beloved community. And so my brothers and sisters, I urge you to have a sense of tolerance, a sense of sensitivity, and create a new spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood within you, because the revolution starts inside of you.

And then finally, the last thing if we want to move from chaos to community is we must never rest in the fight for justice, and we must understand that injustice is often subtle, and that we must stand up against injustice wherever it is found. We must say to our political systems that if they are unjust, they must correct themselves.

And I've got to tell you as one who has been in that system, there are problems that we have yet to address. For you see, I can't understand a nation that is willing to say, give me your tired, your poor if you come from Europe, if you are a refugee from Europe. But yet, if you are Haitian, we ever concentration camp for you.

[APPLAUSE]

I don't understand that. I don't understand a nation that says, if you're from Yugoslavia and the conflict there, come on to America. If you're from Poland, come on to America. Give me your tired, your poor. But if you are from black Africa, trying to escape the warfare of Somalia, Ethiopia, I'm sorry. We can't let you in.

AUDIENCE: Preach.

[APPLAUSE]

GRAY: There's still injustice in our society. And it is incumbent upon all of us to be vigilant and to continue the struggle. And so don't just come here today and remember a dreamer, a historical figure of the past. But go from this place committed to excellence.

Go from this place committed to serve your community and your world. Go From this place being more tolerant and creating a sisterhood and brotherhood of all people, of all colors, and all backgrounds. And go from this place committed that you too, like Martin Luther King, will struggle against injustice. And who knows? One person standing up to the Goliaths of poverty, of militarism, racism, and sexism may be able to bring the walls down as he did.

It's not going to be easy. It never is easy. And it won't be any easier for this generation than it was for mine. But let me tell you in closing for those of you who are prepared to struggle something I learned a long time ago, which has led my life and given me direction and strength.

It happened in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where grandma lived. We used to go visit her every summer. And I'll never forget that day I found out about racism. You know, I saw a water fountain, and I went over to get a drink.

And just as I started to drink, a hand grabbed me and said, nigger, you can't drink from that fountain. Go to the one over there for you. And on the other side of the department store was another fountain with a big sign that said Colored Only. Well, the water looked the same to me.

But anyway, my sister grabbed me and took me home to grandma. And my grandmother was a schoolteacher. And she immediately was confronted, I guess, with the problem that all black mothers and parents have to face, that day when their child finds out that there's something different.

She was faced with the same problem that all Latino mothers and fathers must be faced with when they have to tell their children that there are people who dislike them simply because of their origin. I guess she had to face that same day that the Irish mother faced in the 1890s here in Massachusetts when their child went out and saw the signs, No Irish Need Apply.

But she took me out to the university called the front porch, sat me down in the classroom called the big swing, and she began to tell me about America, about what America was. But she also had a way of taking a negative and turning it into a positive, and talked to me about the could bes of life. For you see, it's not enough to dwell in the past. It's not enough to dwell in the reality of this moment. But life belongs to those who are always looking at the could be of life and who are willing to create it.

And I'll never forget she said to me, son, you see that mayor, the city council, the state legislature, the governor, the Congress, the courts, it takes all of them to keep you from drinking at that water fountain. That's how important you are.

[APPLAUSE]

And she told me then that life was never going to be a bed of roses, and that I would have difficulty. And that difficulty would be put there by other people, regardless of what I did. But my job was to climb the mountain and to overcome the difficulty.

And I'm so glad she did. Because you see, that little boy born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, who later on went to school in Philadelphia, in North Philadelphia, grew up to be not only a minister, not only a college professor, but in the 1980s, he used to sit on the second floor of the White House and look the most powerful man in the eye, the president of America, Ronald Reagan, and say, no.

[APPLAUSE]

And I've learned that the only way you get there is by remembering what she closed the lecture with. She closed with some words that I didn't understand then, and I didn't know where she got them from, but I understand now, because they were the words of another black mother to her son. And they are the words that I leave with you here at this community of learning.

I leave it to all of you who are soldiering through this place, whether you are black or white, no matter where you come from, for indeed, the struggle against injustice is a constant one. And she told me these words.

Well, son, life for me ain't been no crystal stairs. It's had tacks, splinters, boards bare, places where there ain't been no carpet. But alls the time, I's been a-climbing, reaching landings, turning corners, and going in the dark where there ain't been no light. So son, don't you sit on them there stairs cause you find it kind of hard, for life for me ain't been no crystal stairs, and I's still a-climbing.

My brothers and sisters, as we celebrate this day and remembering a spiritual giant that God gave to us and who sojourned and changed our land, we must remember that we too are called to climb the stairs. And I urge you here to reach new landings, to turn new corners, and for God's sake, go into the dark where there ain't been no light.

[APPLAUSE AND CHEERING]

NICHOLS: I would like to thank Reverend Gray for addressing the MIT community and answering the question, where do we go from here? I was very excited to have Reverend Gray come and speak to us today. I am very proud that a fellow Philadelphian has accomplished so much for people at home and abroad.

My father, Marvin Russell Nichols, and Reverend Gray were Boy Scouts together. And my father tells stories about the Grays and the times they had at Bright Hope Baptist Church. The same pride my father feels when he tells these stories is the same pride that I feel right now. Once again, thank you Reverend Gray.

[APPLAUSE]

At this time in the celebration, I would like to invite my peers in the MIT Gospel Choir to perform.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

CHOIR: Speak to my heart, Holy Spirit. Give me the words that will bring new life. Words on the wings of the morning, the dark night will fade away if you speak to my heart.

Speak to my heart, Holy Spirit. Message of love to encourage me. Lifting my heart from despair, how you love me and care for me. Won't you speak to my heart? Speak to my heart, Holy Spirit. Give me the words. Give me the words that will bring new life. Words on the wings of the morning, the dark nights will fade away if you speak to my heart.

Speak to my heart, Holy Spirit. Message of love. Message of love to encourage me. Lifting my heart from despair, how you love me and care for me. Won't you speak to my heart? Speak to my heart. Speak to my heart. Speak to my heart. Speak to my heart.

Speak to my heart, Lord. Give me your holy word. If I can hear from you, then I know what to do. I won't go alone. I'll never go on my own. Just let your spirit guide and let your word abide.

Speak to my heart, Lord. Give me your holy word. If I can hear from you then I'll know what to do. I won't go alone. I'll never go on my own. Just let your spirit guide and let your word abide. Speak to my heart, Lord. Speak to me. Give me your holy word. If I can hear from you, then I know what to do. I won't go alone, I'll never go on my own. Just let your spirit guide. and let your word abide.

Speak to my heart, Lord. Speak to me. Give me your holy word. If I can hear from you, then I'll know what to do. I won't go alone. I'll never go on my own. Just let your spirit guide and let your word abide. Speak to my heart, Lord. Give me your holy word. If I can hear from you, then I'll know what to do. I won't go alone. I'll never go on my own. Just let your spirit guide and let your word abide.

Speak to my heart, Lord. Speak to me. Give me your holy word. If I can hear from you, then I'll know what to do. I won't go alone. I'll never go on my own. Just let your spirit guide and let your word abide. Speak to my heart. Speak to my heart. Speak to my-- speak to my heart. Speak to my heart. Speak to me. Speak to my heart. Speak to my heart. Speak to my heart.

[APPLAUSE AND CHEERING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Looking over my life, I've seen the roads that I've taken. I don't like it, seen some things, some things have got to be shaken. I've checked it out. I've been in this thing too long. Got to change my attitude, it's time to sing a new song.

Cause I've made up my mind, I'm going in another direction. Cause if I don't I'll end in destruction. I'll walk and I'll crawl, but this time, I'm going to give my all. Please don't hinder me. I'm trying to make a change. I'm going all the way, and I'm going in Jesus' name.

Looking over my life I've seen the road that I've taken. I don't like it, seen some things, some things have got to be shaken. I've checked it out, I've been in this thing too long. Got to change my attitude, it's time to sing a new song.

Cause I've made up my mind, I'm going in another direction. Cause if I don't, I'll end in destruction. I'll walk and I'll crawl, but this time, I'm going to give my all. Please don't hinder me. I'm trying to make a change. I'm going all the way, and I'm going in Jesus' name.

My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track. My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track.

My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track. My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track.

My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track. My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track.

My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning, turning, turning back.

My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning, turning back.

My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning, turning, turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning, turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back.

My mind's made up, no turning back. My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track. My mind's made up, no turning back. Yes, I'm happy because I'm on the right track.

Please don't hinder me. I'm trying to make a change. I'm going all the way, and I'm going in Jesus' name. My mind's made up.

[APPLAUSE]

NICHOLS: The MIT community is full of rich talent. Now Linda [? Lipsey ?] Hughes from the graduate school office will perform for us. She will be accompanied by a pianist.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[MUSIC PLAYING, "AMAZING GRACE"]

[APPLAUSE]

Now I will ask Reverend Paradise to give the benediction. And afterwards, I will return to state a few announcements and close the ceremony.

PARADISE: Let us pray. Oh, God, let the words that have been spoken, let the music we have heard, let the lives that have been witnessed to here today sink into our hearts, seize our imaginations, galvanize our wills, and change us. Amen.

NICHOLS: Once again, I would like to thank our keynote speaker, Reverend William Gray, for coming to MIT today and giving us a new perspective.

[APPLAUSE]

There will be a reception immediately following this program in [INAUDIBLE]. That's in the third floor of the Stratton Student Center. We encourage you to attend.

Dr. King's book Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? will be on sale outside in the lobby across the auditorium. Finally, if you view your program, you'll see that there are many events taking place this weekend.

The first is the conference Revolution: The Untold Story, sponsored by the MIT Community Fellows. Then on Saturday night, Journey Into a Dream: A Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, will be performed by Semenya McCord and associates. This concludes the 19th Annual Martin Luther King Memorial celebration. Thank you for celebrating with us.

[APPLAUSE]