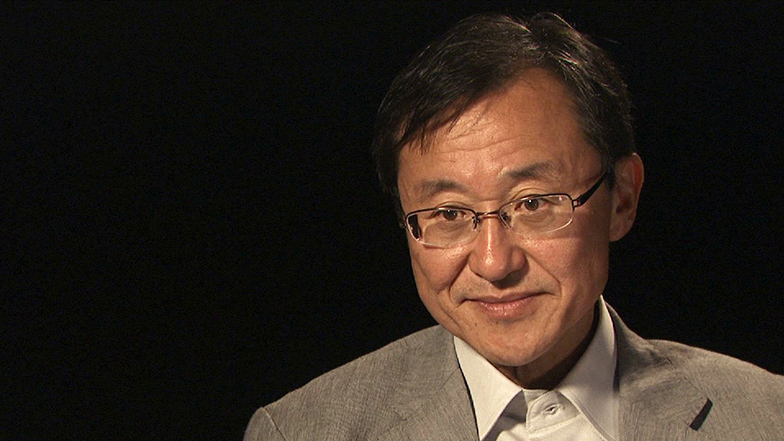

Gerald L. Wilson '61, SM '63, ScD '65

INTERVIEWER: As part of the MIT 150 Infinite History project, we're talking with professor Gerald L. Wilson. Professor Wilson is currently professor emeritus in MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. But his connection to MIT is long and varied. He earned a BS in electrical engineering from MIT in 1961, an MS degree in 1963, and an ScD in mechanical engineering in 1965.

Soon thereafter, he joined the MIT faculty as an assistant professor. He later became the Philip Sporn professor of energy processing. In 1974, Professor Wilson created the Electric Power Systems Engineering Laboratory and became its director. In 1983, Professor Wilson initiated Project Athena, a program that would fundamentally change computing at MIT. And in 1987, he helped create the Leaders for Manufacturing Program, or LFM.

Professor Wilson served as department head of electrical engineering and computer science from 1978 to 1981. He then went on to serve as dean of the MIT School of Engineering from 1981 to 1991. Professor Wilson, thanks very much for coming in today.

WILSON: You're welcome.

INTERVIEWER: So, let's begin with the years before you came to MIT as a freshman. Tell me a bit about where you grew up, how you grew up, your early years.

WILSON: I grew up in a town in western Massachusetts called Holyoke. It was a mill town. I went to, mainly, the Holyoke school system. But from the time I was probably six or seven, my parents tell me, I was always interested in things and how they worked, and what made things work. So I had an interest in engineering very early on. And I pursued those kinds of things while I was in high school. And so MIT was one of several logical places for me to come to, giving those interests. And so I did that.

INTERVIEWER: What did your parents do?

WILSON: My father was basically in real estate. My mother was just a housewife and mother. I had five siblings and I was the oldest. And so when I came from Holyoke High School, I was the first one to go to MIT in probably 25 years. So it was big news in the newspaper. I thought I was really a big shot when I came here. And I learned later on I wasn't, basically, with respect to the environment at MIT.

INTERVIEWER: You mentioned that from a very early age, you really displayed an interest in how things worked. What are some of your early memories about developing interest engineering? Was there kind of an a-ha moment where you said, oh, this is what I should be doing?

WILSON: No, I think it was just that I always had an interest in taking things apart, clocks probably, early on. I remember taking apart tape recorders. I did a lot of-- learned about electronics, read a lot about ham radio. I wasn't able to afford that, but I knew a lot about the electronic side. And I won the science fair in high school. And that's the first time I came to MIT, actually, was to the science fair that was held here in April every year. So I think throughout my career-- I mean, as well as having an interest in academic things, and I also played some sports-- I had a very strong interest in how things worked, making things work, building things, go karts, all the same things loads of kids did back then.

INTERVIEWER: Was coming to MIT a dream that you had early on? Or did you first become aware of it when you came here with the science fair?

WILSON: I hardly knew a thing about it. I applied to a bunch of universities and MIT was one. It was a bunch of letters to me. The first time I really knew anything about it was when I came to the science fair and I was over in what's now called Rockwell Cage. That's about all I saw of it. But it wasn't-- I didn't know-- it wasn't high on my list one way or the other. I almost went to RPI.

INTERVIEWER: So what were your impressions of MIT upon arrival? Tell me a little bit about those early years.

WILSON: Well, I went through-- as I think I referenced earlier-- you come here, a member of the honors society. I had my honors society pin proudly on my lapel. And about the first day we came, we all were assembled over in what's now the armory, it was the armory then. So there's a thousand young men and women. And what I noticed was there were lots of honors society pins. When I went back to my dorm room, I remember taking it out and putting it in the top drawer. And about four or five days later when we reassembled, I noticed most people had taken it off. That was the first learning about MIT. You are amongst some of the brightest people around. And you were just lucky to be here.

INTERVIEWER: So I'm very interested in hearing a bit about your undergraduate experience in terms of developing interests, what sort of caught your attention as someone just starting out in the sort of serious study of engineering.

WILSON: Well, first of all, I got married at the end of my freshman year to my high school sweetheart. We'd been going from probably age 15. She was from Wales, went back home to Wales. And we couldn't stand being away from each other. So at the end of my freshman year, she came here. So I worked about 20 hours a week at the instrumentation lab as well as a student. And I, basically-- there was no UROP program here. So it was basically taking subjects, going to laboratories, and I was, by the junior year, I had begun to question what I was going to do when I graduated. I figured-- another year I'm going to graduate. I was in electrical engineering, generically. Most of the jobs that you were aware of then where in the defense-related businesses. And I thought about that and looked into that. And I'm not a pacifist, but I decided I didn't want to work for Raytheon or whatever making electronics for bombs, for missiles, and so on.

And so I started looking around and I found this undergraduate project program that I went to work, and went to meet the faculty member-- his name was Herb Woodson-- and he was working on energy. And that was a transformative experience for me. I did a project for him as a junior and I moved and decided I was going to work on energy and energy-related activities. And that's what I did.

INTERVIEWER: And so is that what led you to make the decision to continue your education at MIT?

WILSON: Yes, yes. So I did my Bachelor's degree for Herb. And that was on making a shock tube to make plasmas. And the big area of interest then at the time was an area called magnetohydrodynamics, which was using magnetic fields to interact with conducting material, in this case a very hot conducting gas. And they were having trouble taking pictures of the shock tube and trying to measure the velocity. And so I made a-- they would have a camera that was spinning and they'd push the trigger and once out of 10 times they'd-- it was a spinning mirror-- it would be at the right position to record this. So I made some electronics that synchronized the camera mirror and had the camera fire the shock tube so it would always take a picture. And that was a very satisfying, successful, junior project.

So as a result I did my Bachelors' thesis for Herb, I did my Master's and my PhD, all in areas related to magnetohydrodynamics and plasma physics.

INTERVIEWER: So today, of course, energy is one of the key issues facing all of us. Not just engineers but politically, socially, it sort of seems to pervade everything we do. At that time, was it-- you mentioned the defense industry being kind of preeminent-- was there a different sort of feeling about energy? What were the key issues and what really led to your interest on it?

WILSON: Well, the whole area of magnetohydrodynamics was to try to make more efficient energy conversion. And there was interest in that, but it was certainly in the background. And it's interesting you ask that. When I finished my doctorate, Woodson and I decided to work in the area of electric power. The reason was, after the first Northeast blackout had occurred and he took a leave of absence and went to work for American Electric Power, just on a year's leave, to learn more about the electric power industry, and asked me to stay to teach his courses and work with his research students. I had no intentions of being a faculty member or staying at MIT. So I did this-- he'd been my adviser-- so I did this as a favor. And good ol' Herb, he suckered me in. He said, well, when he finished up, why don't you go down to AEP? So I did.

And we came back, and in fact, that's where the-- it was first called the Power Systems Engineering Group. When I came back, we formed that group and I got what was the Ford Foundation faculty professorship, which allowed me to stay for several years. And I stayed to try to help him build that up. What's interesting was it was unpopular at MIT, in particular in our department.

And as an aside, the existing department head and Herb lived on the same street and they would commute in together from Watertown. And there would be times people would see them get out of the car screaming at each other because the department head felt that going back and working in the electric power area-- MIT always was at the forefront of new things, and you guys are working on this old stuff that we finally got rid of a long time ago. And in fact, one of the key contributions of the EE department, in the earlier days, was in making a device to analyze power systems. And there were probably 15 faculty-- rotating machine, transmission-- all working in that area.

And when Gordon Brown became dean of engineering, after being department head, he drove all of that out. He pushed faculty out. There were some faculty that stayed, but their whole area was kind of-- the equipment was given away to the University of Puerto Rico. He just cleaned the decks. So now here's his successor as department head saying, you guys are going back to the old days. And so he and Woodson would have terrible arguments about that. But the problem was that Woodson had gone to the dean, which was Gordon Brown, and Gordon was helping at least finance some of this, in spite of the fact he'd driven it out. But it was a very contentious period.

And so I found myself in a bit of a pickle. Because Herb, after all of the troubles here, was asked to be dean at the University of Texas at Austin. So after I was on the faculty about two years, and supposedly going to be finishing up pretty soon, he leaves. And I'm here with this lab with a bunch of graduate students working on electric power. And now I would meet with the department head. And the meetings were not fun always. One time he referred to us as a bunch of garage mechanics. Now, to his credit, years later he put me up for a promotion twice. So it's not like he carried a grudge. But intellectually, at that time, work in the energy area was not the most popular thing to do. But we believed it was the right thing to do and we did it.

INTERVIEWER: Well, it's fascinating how things turn, with the intense focus on power grids, on the power grid now, it's--

WILSON: Total flip.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. Very interesting. You've spoken a lot about Professor Woodson. Were there other colleagues, classmates, mentors, memorable people from your early years as a student and young faculty member that are worth talking about?

WILSON: Oh sure. Well, there's certainly-- I didn't have anyone else I interacted with as strongly. But there were people in the department-- Sam Mason and Zimmerman-- who were very influential in terms of their approach to life. Sam Mason was a very smart, older, experienced faculty member. And he was really one who looked out for students. And I remember one time we were having a doctoral oral exam. And this poor fellow was up at the blackboard. And there would be three faculty members in the front row. This one would ask him a question, then the one to the middle, then the one to the left, then the right. And the poor guy is going back and forth. And Sam finally stopped and said, why don't we-- you keep coordinating and maybe we can get him to totally spin around while he's up there. He really was very good at caring for students.

Another person that had a lot of influence on me was a man named Charles Kingsley who was a rotating machinery expert. And he and I became very fast friends. And until he died, we were good, good friends and colleagues. And one of my former students took over-- Kingsley and Fitzgerald, who was here, wrote a text on rotating machinery. That text was and has now, internationally, probably the largest distribution of rotating machinery textbook. And in the United States it's printed in many languages. And my former student started work with Charles. Charles has long passed away but the book is in its fifth edition. Steve Umans is the author of it. And we've carried Charles' legacy on for a long time. But he had a lot of influence on me and other students.

INTERVIEWER: So I'm also interested in the environment of MIT in the early to mid-1960s. I would imagine that there were things that were very different about MIT if you compare it to now and things that might have some continuity. What--

WILSON: Well, the first thing that happened when I was-- I came here in 1957. And within a year or year and a half, I believe, after I was here, the Russians launched Sputnik. And all of us commented, within the next year and a half, we noticed a sudden, significant increase in the intensity with which the faculty and the whole place was focused on science and engineering, and our position, and the position of this country. And it made for a very intense environment anyway.

And it is very-- and was very-- different than it is today. We had classes on Saturday mornings. I could not spend a weekend goofing off if I was going to survive. You studied on the weekend. And I wasn't alone. Most of my colleagues-- there was very little time for fun and games.

That's very different today. I have students today that tell me, oh I don't do homework on weekends. So the intensity of the place has changed. Now, a lot of people say for the good. Paul Gray used to-- probably still does-- refer to drinking from a fire hose. But that was what it was like. There were more subjects. And I think the demands on your time were much more stressful than they are today. I'm not saying it's all to the good, but that's certainly the way it was.

There was a lot less opportunity to experience what being an engineer really was like here. You went to classes and trotted through all. You did some labs. But you never had the opportunity to find out how it related to the real world. And engineering really is bringing science for the benefit of mankind. So you really need to understand the other side of where it's going. And there was very little opportunity to do that. I did that with that junior subject. But that was an accident. And it shouldn't be an accident. Well, the UROP program that exists today, that Margaret MacVicar started, is a major influence on the change in students lives. Students have an opportunity, from the freshman year on, as you know, to-- you don't have to wait four years before you can try to do something. You start working with faculty and students and people in research. And you get an opportunity to see what it has to do with. And you can make a lot of decisions about your career. And it certainly made a serious decision for me. It helped me make a very serious decision about what I was going to do. The business of staying here on the faculty was an accident. But certainly, being in energy was a result of that experience.

INTERVIEWER: So, turning back to energy, tell me a bit more about the formation of EPSEL and its development over the next few years-- its goals, difficulties.

WILSON: So we started what was called the Power Systems Engineering Group. It was focused on the electric power system. Well, both of us went and spent a year at American Electric Power. We came back and brought back problems that that utility was having. At the time, it was one of the largest utilities in the United States. It still is. So we had practical experience in that entity and came back with projects related to it.

When I was at American Electric Power, I was up on catwalks 300 feet, out checking out control systems, installing, designing control systems. So I came back with some fundamental research projects to work on. And that was the genesis of the early laboratory. But the other thing that Herb and I did was we began to find other people, either who were on the faculty or recruited to MIT, who would go and spend a year at American Electric Power. And by the time we finished, there were like nine faculty members who had gone there, both in mechanical, electrical, one in chemical.

There was a fellow, Fred Schweppe, who was at Lincoln Lab studying state estimation theory for defense systems. And we convinced Fred to come here. Fred Schweppe unfortunately passed away probably 15 years ago. He had a heart attack while driving. But Fred brought those tools to the electric power industry. And one example is something called state estimation. It is now used throughout the world as the way of estimating and controlling a power system. It started with Fred here.

There's, right now, a thing you hear about co-generation and co-energy. Fred had ways of thinking about that and thinking about the pricing in a power a system like pricing on a stock market. This was 20 years ago. Well, those ideas now are part of-- when you hear a lot of the hype, but there's also some useful things about smart grid. That's Fred Schweppe.

Now, that happened because we brought him from Lincoln Lab. He spent a year at American Electric Power. He changed that industry. So the lab had a lot of influence. I worked on 765 kilovolt transmission. American Electric Power's building lines, they had trouble with something called audible noise, where fog would drift in, condense on the wires, and because it was in a very high electric field, it would make a hissing sound. So people living near the transmission lines not only objected to their looks but now would hear frying eggs in the morning if it was foggy. We worked on a way of solving that.

We built with Herb-- Herb still started it. I finished it after he left. We used superconductivity to build the first superconducting generator in the world. That all happened here. Superconducting generators are not yet used on the large scale in power systems. But there's a lot of work on superconducting motors and an application to superconductors to transmission. So the lab evolved and grew. When Herb left, there were seven or eight graduate students and two or three faculty. Before I became department head, we had grown to probably six or seven faculty. There were about 30 graduate students. There were probably seven subjects, graduate and undergraduate. Before we started there were none. And so, it had a major influence on MIT in terms of that electric power side of the energy area.

INTERVIEWER: And then later it became LEEs, right?

WILSON: Right. Later on, after I became department head, we brought a fellow named Tom Lee who-- I brought him here. He was a General Electric engineer, researcher in the circuit breaker area in Philadelphia. And we brought him here. And they changed the name to LEEs, for Laboratory for Electronic and Electromechanical systems. So they broadened it to include electronics. So it all came from that.

INTERVIEWER: So, earlier you mentioned the very significant involvement in the defense industry that MIT had in the 1960s and some of the contention that created.

WILSON: Right.

INTERVIEWER: I wanted to ask about the environment on campus at that time, I guess, at that point when you were a young faculty member just making that transition of being in the faculty-- what that was like and how you were affected by it or had to deal with it.

WILSON: You mean in terms of the contentiousness? Oh yeah. Well, it was-- I'm not going to be very good with dates here, but-- probably the early 70s. The student feelings about the instrumentation lab had students working on making multiple reentry vehicles, which were missiles with multiple targets. There were students doing their theses on this. And there was a great objection to the Vietnam War. And those on this campus came together. There was a Students for a Democratic Society started collecting and organizing to object to a lot of this. And it grew. We had, as I said earlier, an AWOL soldier. It grew to finally students trying to prevent workers from going to work. So there was this police activity that was necessary, from the administration's point of view, to push them out.

There were days you couldn't walk up the front steps of Mass Avenue. There were students trying to block you from coming in. There were a lot of bad feelings generated on both sides. The faculty got somewhat polarized. And I never saw it break out in terms of arguments or very strong arguments between faculty that got at all physical. But there was a quiet disparity between those that supported the war in Vietnam and those that did not.

Its affect on the place was twofold. First, Howard Johnson came in here as president. And there was an opportunity, and I think he had an agenda, for making some positive changes at MIT. And he was totally deflected by this. So his whole administration really was focused on this business. And it culminated, finally, where there were discussions about what MIT does with its relationship with what was called the Instrumentation Lab at the time.

Now, it was started by a man named Doc Draper out of the aero department. And it became the focus of faculty meetings where lots of heated arguments went on month after month. And it was finally the point where the students were pushing for us to divest. And it finally culminated in a faculty meeting that was held in Kresge normally we go to faculty meetings, we have 1,000 faculty. I don't know, maybe it's more now. But you might find 80 people there. These faculty meetings were packed. And it was held in Kresge because there wasn't room in 10-250 where they normally were held. And then were contentious issues about, should the people from Draper have a right to speak? Because they're not faculty members. And the rules are, only those who are members of the faculty could speak. And yet this was affecting their lives. And so there were all these kinds of-- so there'd be committees to try to deal with that. And it was-- it was bad. And it certainly de-focused MIT from its main mission of education and research. And finally, the decision was made to divest. And Draper eventually moved-- I'm sorry, Instrumentation Lab eventually move to where it was. And to show us how they felt about us, they renamed it, Draper, a man they really respected. And it moved off and separated. And finally the war went away. And things eventually got back to normal. But for five to seven years, it was a harmful process for MIT. And yet, at the end we went through it. We worked out answers through it. And so people were probably more prepared to deal with problems in the future having gone through that without the place blowing up. And it never came close to blowing up.

INTERVIEWER: So I'm just curious, you mentioned that you actually early on as a student worked at the Instrumentation Lab?

WILSON: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: Did you ever have any interactions with Doc Draper or-- it sounded like you decided early on that that wasn't the path you wanted to take.

WILSON: Right. Well, actually the things I worked on were fun. It was to do with the moon shots and missile shots and space. So I got to work on a lot. No, I met Doc a couple times. I didn't know him well. I have a lot of colleagues that knew him well. And he was around here a long time. There were a lot of well-known people here. One was Draper. Norbert Wiener used to walk along the halls, you'd see him. But I didn't know Doc on a personal basis.

INTERVIEWER: So, moving sort of back to the 1970s, eventually you became the chair of EECS. Tell me a bit about how that came about and what some of your vision and goals were for EECS at that time.

WILSON: Well, the department at the time had about 100 people, faculty members. I was located in the basement of Building 10. The department had built the new building that it now is in, either 36 or 38-- RLE and the department together. I was fairly isolated. And I didn't know much about-- I would go to department meetings. But my head was focused on-- first of all, Herb Woodson had left. I had inherited a bundle. I mean, I was now carrying a huge load in terms of fundraising and number of students. I think I had 15 students at the time. And I was director of the lab, and faculty, and space.

And so I was dealing with all that. And what happened to me was that one day the institute came and asked me, would I chair the commencement committee? It looked like a pretty innocuous thing, so I looked at it and talked to the guy who had been-- aw, you just chair meetings and they get ready, they run commencement. Don't worry about it. So I agreed. And within months I learned-- I used to always go to commencement-- I learned that the students get, on average, two tickets. There's room for two tickets per student. They can go around begging to faculty members. Each faculty member got a ticket. And students would go round trying to get another ticket so maybe their grandmother could come or their brother or sister as well as-- I thought that was terrible. And so, I went and sat through and we ran the first commencement. But I said, we've got to find another place to have commencement.

So we started-- and when I say I, I chaired a committee. The ideas were not Wilson's. The ideas came from all over the place. For everything I've done, the ideas came from all over the place. But we began to say, we ought to move this thing to Killian, which was called the Great Court at the time. It's now Killian Court. And we started talking about that. We had someone from Physical Plant. We had someone that ran and gave out commencement tickets. And we started working.

And I'll make this shorter so it isn't too long. I was given pictures of tents that had been put up in Killian, Great Court, in the '20s-- pouring rain, tents laying on the ground, all folded over in mud. This is what's going to happen if you try and move commencement. Don't move commencement. There was a lot of opposition.

Jerry Wiesner was president at the time. I never asked him. I just kept working on this. But Jerry Wiesner used to say about MIT, don't go around and ask. You see something you really think you want to do and should be doing? Go ahead and do it. As long as it's legal. But don't go around asking to do it. So we started working and to make a long story short, pretty soon we were going to move commencement to Killian Court. We made plans for that.

One of the questions was a stage. And the stage that you see out there now we had designed and was built in Physical Plant. And one of the major arguments is you'll see a sail that's over there to cover the faculty so, god forbid, they should get sunburned while the parents do. And the sail was designed by Jerry Milgram who was a faculty member in ocean engineering. And I got Jerry to design the sail. And now, we were going to tie it to the parapets of the Killian Court. And the Physical Plant said, you can't do that. The building can't withstand that. So Milgram and I, but mainly Milgram, did a lot of analysis and calculating loads-- if there's a wind on the sail, how much will it lift? And where are you going to tie it? We decided we're going to do it. And we went ahead and had a sail made and put it up.

And so we're all-- everything's wonderful and we're going to have our first commencement there. And most of the community is supportive. People are saying, you wait until it rains. And so the night before, Mary Morrisey, who used to be the one who ran the area that distributed tickets and ran a lot of the flowers inside, et cetera, and the organization of commencement. And Hank Leonard from Physical Plant and I came the night before. And Leonard and I stayed at the Hyatt Hotel and heavy rain was predicted for the next day. We had 6,000 chairs out in the court. And what was a side issue was we were in a bar at the Hyatt down the street and Howard Cosell-- you probably don't know who Howard Cosell is.

INTERVIEWER: I do actually.

WILSON: Right? Howard Cosell was there for I don't know what. But there was a football game or something. Maybe Muhammad Ali was punching somebody. But anyway, he was there. We ended up drinking with Howard Cosell until around 1:00 in the morning instead of going to bed.

We got up real early and rain was predicted. Disaster. A person in the MIT meteorology department-- he was doing the weather for us-- he said, this rain will stop at 9:30. Then the sun's going to come out. And he was-- we thought, this is pretty precise stuff. So he said, it'll end. So we got, I don't know, 40, 50 people with towels. And they went out. And at 9:30 it stopped raining. They went out in the court and wiped all the 6,000 seats. And commencement started at 10:00, and the sun came out. It was fine. Thank goodness. Luck.

And so, the reason I tell you that story-- no one knew who I was. And I think within a year or two, out of the blue, I was asked to be department head. But I think that's what got me into trouble. So I don't know. I mean, there was a search committee. I never played with the politics. I didn't know who they were thinking about. I believe they asked someone else first who turned it down. And then they asked me.

INTERVIEWER: Because the sun came out?

WILSON: I suppose.

INTERVIEWER: So was there a back-up plan? Were you going to move to Rockwell Cage, or?

WILSON: No.

INTERVIEWER: There was no back-up plan.

WILSON: Now there's back-ups and all that, we load up chairs all over. But for the first six or seven years-- but a lot of things we did there that had some influence. For example, there was a proposal that the parents should be there, the students should march in and sit down, and then the faculty should come in and go up on the stage. And I said, this is upside down. The students are the ones who are to be honored here. The faculty come in and wait for the students. And that's still what's done. But there was some push.

INTERVIEWER: So, when you were offered the EECS, when they offered to make you department head, did you feel then that you were-- I don't know if outsider is too strong a word-- but that you were kind of coming in, in a way, having been preoccupied with other things and not really expecting it?

WILSON: Well, I certainly-- the outsider is not strong. I certainly felt-- I probably knew 20 faculty members. There was a whole computer science side and there was a lot of argument and discussion about whether electrical engineering and computer science should be separated or kept together. The genesis of computer science came from the department and so on. But they were over in Tech Square. They felt isolated. I knew none-- I didn't know any of them. And I did not know most faculty. I was surprised that they asked me.

But I'd always been probably vocally critical about a lot of things. And so when I was asked-- it wasn't something I was looking to do, but-- I thought, if you don't take it then you're in no position to criticize in the future. You're going to have to shut up. I didn't think I could do that. I couldn't teach myself to do that. So I took it and decided I'd do it.

And I chose Richard Adler who I did know, from the EE side. And I asked around and Joel Moses, I asked each of them to be associate department heads. And I just jumped into the bath and started.

INTERVIEWER: So what were your goals? What did you feel were the burning issues of the moment?

WILSON: When they asked me, I had no goals, of course. Right? People always-- after they asked me to be dean someone came and said, well what's your goals? I had no idea. I wasn't going to be dean, what the hell do I know about goals? But I spent a couple of months. I talked to every faculty member. And I learned a variety of things. I learned that it was the EECS, but there was a need, and there was already some motion, to try to develop subjects that integrated the two disciplines in the sophomore year. And so we had people working on that. There was the whole area of integrated circuits. We, MIT and some of our earlier faculty were certainly some of the contributors to the ideas of taking instead of discrete components, and now making them on an integrated plane and using that technology.

The department had made a decision about five or eight years before that they were not going to have a facility to make integrated circuits because it was too expensive. We'd never be able to afford to run it. And the strongest opponent-- proponent for not building that-- was Richard Adler, who now is the associate department head.

So I started talking around. And meanwhile, students at Stanford and Berkeley could have integrated circuits made. And I thought, MIT is always criticized for doing all the theoretical stuff and not enough practical. And I thought this was a case where students-- there's a big difference between laying out something and how you hope it's going to work and building it and seeing if it works. So I became convinced that it was a real hole and probably part of the reason that the East Coast, which was initially the electronic mecca, was being displaced by the West Coast. Because Berkeley, Stanford were pouring out students that had these skills. And we were pouring out students that had the skills, but they didn't have the practical side.

So I started going around talking. And I was convinced we should do this. Not by my own ideas, but loads of people told me that we should do it. But there were some who felt that the earlier decision was right, one of whom was Richard Adler. We would have arguments, good arguments, in my office about doing, not doing. And I finally said, I'm not going to do this if Dick doesn't agree. And over a couple of months I convinced him.

And it was a huge undertaking. Because now we were going to go raise the money. We had to find a building. So we found Building 37. We had to move people out. And we had to get MIT to sign on. And Paul Gray was president. Paul Gray never turned me down on any proposal. He was always very supportive. And we gave him-- I had people in the department give a price. We gave him what we thought the cost would be based on their analysis. And we went out and started raising the money. Paul discovered, or we all discovered, it was going to be three times what we thought. Paul never let me forget that. But he forged ahead and we all-- and Richard Adler worked to raise money. He worked very hard. We finally found a director, Paul Penfield, who was a faculty member who now believed this changed his field and became very knowledgeable about that. And we started hiring young faculty.

So in the three years I was department head, we started that-- the Microelectronics Center. And it's still out there cooking. You can go out and see the liquid nitrogen freezing all the pipes. So it's a facility that students use and a lot of faculty use. And so it was one of the things that I did.

INTERVIEWER: So, I'm always very interested in hearing people's takes on balancing research interests, and how those are evolving, with the kinds of demands on time that having a position like that, let alone dean, make on you for fundraising and organizational management. How do you, or how did you, manage to balance that?

WILSON: One of the things I stopped doing I really missed is I stopped teaching. I mean I couldn't be out running around trying to raise money for that and some other things and trying to meet a schedule of students. I really think it's disruptive if you're teaching a subject but half the time it's someone substituting for you. So I stopped teaching. I continued to run the laboratory while I was department head. And I just spent a lot of time here. But I had a lot of help. I mean, one of things-- if you, at this place, if you do something that there's a subset at least of people that believe you're responding to a need they really believe in, they put their money where their mouth is. And so a lot of people helped. And in that integrated circuit facility, a lot of faculty came together. We started hiring people. They went and identified faculty. They started developing subjects. And I didn't micromanage this. I just sort of said, we build that facility and around that the faculty just responded.

So I didn't do all that myself. I had a lot of help. And so it was not a killer. The other thing was that there were two buildings there, 36 and 38. There was supposed to have been a building between them. And so we had built this facility. There were no labs. There were offices. If you go look at those two places, there were offices, there was no lecture hall. There were no new classrooms. So EE was still-- the classrooms were all over the place.

So I got it in my head that I wanted to try to build a building there. And so I decided-- I think I talked some with Paul Gray about this. But I decided that we ought to build a building. And we'd say, there's lecture halls, there's labs, there are classrooms. There's no offices. We're not even building bathrooms. We'll use the bathrooms in Building 38. But it should go in that spot.

And so I went to Physical Plant and to Bill Dickson, who was a friend of mine. And Dickson said, you can't, you can't get a building in there. It's really going to be hard. I don't give up easily, so I found a classmate of mine who was building a lot of construction in the Boston area. And from Holyoke, my father's good friend was a guy named Daniel McConnell who ran a big construction company. And so I asked them to come and look at the site and tell me, could we build a building there? Oh yeah. And they looked at it and came back. Yes, this is how you could do it. And there were issues of fire trucks getting through and all of that. Then we finally got that. And then it was a matter of money. And so you've probably heard a lot-- you must have heard a lot about Harold Edgerton. So I won't--

INTERVIEWER: Oh, no. No. You should--

WILSON: You could go on and on.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, you could. Please.

WILSON: I knew Doc really well. And Doc and I had a long history because me with my plasmas and capacitor banks, and so on. And he would lend me equipment and high speed cameras, so I knew Doc. So I went to Doc and I said, I want to build a building here. And I told him what it was. And I remember, we took him-- there was a walkway between the two, 36 and 38. And I brought him up to the third floor and I said, I'd like to put it about here. I said, I want a lecture hall. Oh, he said, well that's easy. You want a lecture hall, you get a blackboard and you get a bunch of chairs. I'll help you. We'll get a bunch of chairs and there'll be a place, right down outside. He was giving me a-- but he finally agreed that he would help pay for part of it.

And then Paul Gray said, why don't we go to Germeshausen and Grier, the other two partners that started EG&G? And Paul went out-- I don't think I went with them. I think he did this entire thing. He was president. He grabbed it. And he got the money-- I got it from Edgerton and he got it from Germeshausen and Grier. And we built this impossible building. And the faculty was totally benign. I kept saying-- what do you want in this? Oh, whatever you want, because they didn't think it was-- it had been tried so many times. It's not going to happen. So it was going to be a three-story building.

And then when it started to look like it was going to happen, a bunch of faculty came to me and said, we really need a lab on the fourth floor. And I said, well why didn't you-- but I went back and we put a lab on the fourth floor. I think it's the fourth floor. I think it's the fourth floor. Maybe it's the fifth floor. But anyway, when we went to build that, Doc came over. And Doc liked doing time capsules. So down there, he and I went into a hole and digging with a shovel-- there was a group of people taking pictures-- and we put this time capsule with all the remnants of the time and built the thing.

INTERVIEWER: So, in this space of one story, you've mentioned a couple of MIT legends, and certainly Doc Edgerton is someone who looms large. And in a different way, Bill Dickson also.

WILSON: Oh yeah.

INTERVIEWER: And I want to ask you about each of them. What were your earliest memories of Doc Edgerton? Do you remember how you first met him and what was going on?

WILSON: Yes. There used to be a Course 6 steak fry. And I don't remember what the reason was or whatever. But they would barbecue steaks and would use the laboratory in the basement of Building 10. And they'd unroll brown wrapping paper on top of all the lab benches and they'd be cooking steaks. And the students would all get together with faculty. And Doc-- there was this guy playing the banjo going around-- I think it was a banjo. No, maybe just a guitar. But anyway, it was Doc singing. That's when I first met Doc. And he also could play the spoons. So he would go around bench to bench, doing as he always did, making small talk and jokes with students. I mean, he was already very well known. And students loved to be around Doc and that's where I first met him.

And then later on I interacted with him in a variety of ways, mostly with equipment and banter. If you met Doc in the hall and he didn't know you, he'd come up-- hi, I'm Harold Edgerton. He'd give you a postcard with a bullet going through an apple, or a drop of the milk in a red bath. And he was a legend.

INTERVIEWER: And Bill Dickson as well. Now, Bill-- I don't know if you would have overlapped with him or not as an undergrad. He might have been right before you.

WILSON: No, he was-- I think he was '52 or something. He was about five years before.

INTERVIEWER: So tell me a little bit about that friendship or that relationship, how that developed.

WILSON: Bill-- I knew of him. And our lab moved to the base of the Building 10. We started in Building 3, but now we had expanded. We moved to the base of Building 10. And several times there were instances where the floor would be flooded with an inch or two of water. And it turned out to come from a work room next door that provided cooling for the president's office. And once in a while, a pump seal would fail. And the pump is sitting there. No one's watching it. And we'd come in in the morning and we'd be sloshing in water. It happened once, they cleaned it up. About eight months later it happened again.

And by the third time, I was getting really fed up. So I had tried to talk to people in Physical Plant, the normal rigmarole. But it would keep happening. And we had a lot of equipment there and students. And it was getting annoying. So I went and had the technician-- we collected a little bottle of this green water and put a stopper in it like a test tube. And we called it, I think, the Power Systems Engineering Group Spring Water, or Well Water, or something. And I had him deliver it with a letter to William Dickson saying basically-- this is my arrogance, when I was young I was probably more arrogant than I should have been-- that I'd really like him to fix it. But fix it, or else I'd go up to Central Square and pick the first plumber that drives by and bring them on. And I'll get him to fix it, and it won't happen again, implying that Physical Plant didn't know what they were doing.

Well, we got to meet each other as a result of that. And we talked about putting a containing wall around it, and they did that. And it fixed it. But then the banter between Bill and I continued. And I don't remember all the fine structure, but we got to the point where we would just get together, especially when I became department head and certainly when I became dean, we would meet and get together. Bill was a very, very straight shooter. He was very good politically, not just at MIT. He lived in Framingham. There's a bridge with a bronze plaque with Bill's name on it after he died. So he was involved with town politics and so on. But Bill and I and Hank Leonard, the guy who was a Physical Plant guy with commencement, and Gene Bramer, who later became-- I think he became head of the Facilities of Physical Plant-- anyway, we'd start playing golf once or twice a year. And there was lots, lots of jokes.

And one time Dickson, when he teed off, he hit some pole and a bunch of birds flew off. So I went and got a pigeon stuffed and presented it to him at Academic Council-- because by then I was dean and he was on Academic Council-- with a bullet in it, I mean, with a golf ball stuck in the side. But Dickson became a very capable guy. And he did a lot of good things for MIT. And he was a good adviser and worked both ways.

INTERVIEWER: So after being head of EECS for several years, you went on then to become dean of the school of engineering. Tell me a little bit about how that came about.

WILSON: There was a search committee. I had been fairly active on what was called Engineering Council. Robert Seamans was the dean and the dean, under the Wiesner administration, the dean had pretty much lost a lot of his authority. And Seamans was asked to do it on an interim basis really. He did it for two or three years. And there was a search. And I had no idea-- it was just like the department head. I knew all the players now. But I didn't know who they were-- and they came and asked me to be dean.

And I agreed. I'd only been department head three years. There were people in the department that were not happy about my leaving the department. Herman Haus, in particular, came to me and tried to convince me that I should stick to the department for a little longer. But there was a lot that needed to happen, I think, in the school. So I agreed to do it. I didn't have a strategic plan or an agenda. I just felt it was an opportunity to do something. And so I decided to do it after much discussion with my wife, who was by now getting tired of my going to chicken dinners as department head. But we agreed we'd do it. So that's about how it happened.

INTERVIEWER: What were some of the big issues and big challenges for the school at that period?

WILSON: There were several. The major one was the whole issue of computational facilities for students. And I'll come back to that. And secondly-- and I didn't come in with all this. I knew that was an issue. I didn't know how widespread it was. I certainly knew it was an issue in the EE department. I had gone into Building 36 because I was told students would be there at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning waiting in line to get on a PDP 1140, a small DEC computer.

I came in one morning, because you hear stories about it. I came in twice, just came in at 2:00. There was a line. I thought that was terrible. But I thought, well maybe it's just endemic to the department. And I was starting to do things in the department to try to address that. But after I'd been dean a couple of months, it became clear that that was an issue not just for the department but for the school and maybe for the institute.

Secondly, America was losing its position with respect to manufacturing. And manufacturing wasn't given a lot of attention. And I'd heard some of this in the EE department. But talking to faculty after I became dean, and some of the department heads, I knew it was somewhat on their minds. But it wasn't a major issue. But when I talked to people in industry, it was a major issue. And what to do?

And there were also issues about undergraduate education and the whole accreditation process, which I had never really been much involved with. But I became somewhat knowledgeable of that. There were a lot of lab directors that reported all over the place. But they were labs in the School of Engineering. And I thought that reporting structure needed to change. So there was a variety of things. Though, I remember a man, a fellow named Dan Roos, who was on the faculty, came to me about two weeks after I was dean. He said, Gerry, okay, so what's your agenda? I said, I don't have an agenda. What? How can you-- you're dean. How can you? I said, Dan, I'm working on my agenda. He was sort of stunned that I didn't know what I was going to do.

But it became clear what had to be done, the first of which was the issue of computing and computing resources. And Joel Moses-- Joel was now department head at EECS-- and Mike Dertouzos described to me that they had been trying to get the administration, the previous administration, Walter Rosenblith and Jerry Wiesner, to address-- and they wrote suggestions. But there needed to be many more computing facilities here. And nothing happened. They just lied dormant on desks. And so, that started a discussion in Academic Council, I mean in Engineering Council. And I heard from other departments that there really was a serious lacking. I went out to Stanford and Berkeley and saw they had better facilities for students. So the question was, what to do?

And we would start-- we'd talk about it in Engineering Council-- but I formed a subset committee and we just started talking. And the drivers really were Dertouzos and Moses, Dertouzos in particular. And with all of that, a concept began that we would go to DEC and IBM and see if we could get them to help out. But for me it was, they're not going to just help out by mailing equipment. What is this all about? And I learned that operating systems for controlling lots of individual computers were really not designed to do that well. And I learned that there were many-- people saw many opportunities to develop educational tools.

So I said, okay, now if we go and propose that we will work with this computer company to develop educational software that would be used on computers and would open up new markets-- and I didn't realize how big an issue it was-- but develop all of the tools to manage all of this. I don't mean manage it environmentally, I mean manage it computationally. You've got all these-- who gets on, who logs in, all of those issues were all over the place. I don't think I appreciated how complex and what a challenge that was. I'm sure Moses and Dertouzos did. They knew it better than I did. But I was surprised later on.

So anyway, we went to go and do this and we decided to go to DEC and IBM and ask them to each bid and we'd pick a winner. Talk about arrogance, but that's what we proposed. Would they be interested and support it? So we wrote a whole proposal and submitted it to them. And when I started doing this, I really began to worry about the rest of the place. So I went to, I think Howard Johnson and probably Paul, but I think Howard Johnson. He was chairman of the corporation. And I asked the other deans, do you want to do something together? And the School of Humanities-- I mean, well computers and humanities-- what has that got to do with us? School of Science, they weren't that interested. The Sloan School, Abe Siegel was dean, was a bit of a problem because he said, we're working with IBM. We're going to get our own. We're going to do our own thing with IBM and we don't want to play with that, so okay.

So we went off on our merry way. We wrote the two proposals. IBM and DEC both responded. I mean, this is with hundreds of millions-- not street value, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of computers-- and people. This was going to require people from DEC or IBM to come and work with us and finding some faculty members to stop doing what they normally do to try and create this whole system. And we finally decided to give it to DEC.

And all of a sudden Johnson wants me to come and meet with him and members of the corporation. And so, I think-- I don't know if it was an official meeting. But there were like six people. And Howard was there. And they said, if you can do this with the School of Engineering, what about the rest of the place? I said, well, I'm worried about that. We can't do that. It's just-- we can't do that. So I went back. And talk about chutzpa-- we'd now told IBM, no. You lose compared to DEC-- I mean these two. And we went back and created a proposal for IBM to do the rest of the institute, so the Sloan School, Science and Humanities.

And they did. They agreed. But we had a problem. They couldn't even be on the same floors of the building. There are people that are here because-- they're not supposed to be colluding or working together in any way. And there were lots of issues. And so we separated them. And then, there were a lot of tough problems with all of it. There were people-- the haves and the have-nots-- we picked the best one for the School of Engineering. And the other schools get stuck with this. People in Humanities wanted to know, what the hell are we going to do with all this equipment? And what kind of equipment? And people in computer science-- at the time there was a whole language call Lisp that was invented here. Lisp is a very-- I gotta be careful what I say here-- it's not a straightforward language. It was taught to our undergraduates. But the world isn't Lisp-ing.

But there were faculty who had shirts made about Moses and Dertouzos and Wilson that said, they'll take one guano -- or bat manure. We'll take anything as long as it's free. And here we're taking all this DEC stuff when we should be getting Lisp machines for everybody, whereas people in-- I remember there was one-- Jim Kinsey one day was trying to argue with Dertouzos about that they ought to have a say on what kinds of equipment and so on, and the software that'll be available. And Dertouzos said, you've got to leave this to the experts. We're the experts. We'll decide probably what you should have. And Jim Kinsey says, if you're going to hand out surgical kits, you'd better start teaching us how to saw, how to operate. You can't just hand us this stuff.

So there were lots of back and forth. And then there was a group of people led by Jerry Saltzer, who was a faculty member in the computer science, and he agreed to peel off everything he was doing and lead the whole design and organization of this system. He did a phenomenal job for a year. I mean, his own career he blew away and did this and started pulling together people to work with DEC and IBM. I think-- I may be fuzzy in this-- Jim Bruce was the first director of what-- and we'll talk about-- and Athena, which we called Athena. Chryssostomos Chryssostomidis' wife suggested that's Athena with many heads. It was a good name. So that's where the name came from.

And there was a lot of effort now to organize this. So Jim Bruce did it. He was now running IS for IT for MIT. So he did it for a while. But then I got Steve Lerman and then, years later, others ran the thing. And all of sudden now, we assembled hundreds of people to start Athena and we started getting equipment and dispersing it. And I don't remember the numbers now, but I believe it's 8,000 to 12,000 sites around the campus. And there was a very focused activity-- $20 million-- to take proposals and fund faculty who had ideas about using computers for education.

It transformed the place in a lot of-- I mean, there were people who were going to make programs that would parse languages, you could speak-- it would be a generic program, you could speak Italian, Spanish. There were all kinds of-- there was synthetic simulation of chemistry experiments. You could try this and that without having things blow up in your face. Lots of very talented, innovative, creative activity. And that went on for five, six, seven years. And eventually, Athena-- I don't know how many, I think there must be 15,000, 20,000 sites here went into all over the place.

And there was some 25 years celebration about-- I think two years ago. And I'd learned-- there are key parts of Microsoft Windows and other operating systems, and in Apple, that came out of Athena. The Kerberos, the user identification there, they're buried in that. So that was a side effect. But a lot of the software and a lot of the protocols, et cetera, that were designed went well beyond MIT. It really made a difference in the place. And I could come in and find students all over. And we had a lot of sites on campus. There was a whole thing of dealing with the fraternities, how we're going to get networks over there. Did students have to buy these things? All of those issues. And it all worked. And all I did was listen and take orders from all my boys and girls. They did it I just watched.

INTERVIEWER: So, just a couple of questions I'm curious about, to follow up. Looking back, at sort of the pre-Athena situation, can you describe a little bit more about what computing was available at MIT, how things were organized and what was inadequate about it? And I'm actually asking because my very earliest memories of computing, when I was probably 10, 11 years old, was not at MIT but at Stanford, at their sort of main computer center. So I actually have kind of a memory of what it was like there. And I'm just curious to know what it was like here and what wasn't working.

WILSON: I think mainly we were a mainframe place. So you had terminals that tied into mainframe computers. And computing was mainly focused on analytical modeling, on software that would be used to execute mathematical models of situations. There were things in the computer science department-- they had very modern toys, if you like, and a lot of interactive stuff. And they were doing a lot of exploration. So they had very modern tools. And I think people in the media lab here, Negroponte's area-- they had a lot of tools for using computers for interacting and media interactions. So there were hotspots. But an average student who had a homework problem and just needed something to-- like today you'd run on Mathematica or on some symbol-- on Matlab or so on. There was nothing.

So they would go beg, borrow and steal. And they would get so much time and that was it. It was very restrictive. I'm no expert on what happened in a lot of the other departments. All I heard was it was bad and so I started working on it. But I think there were spots in civil engineering that if they did research related to computers and so on, then they had tools. But the rest of the place didn't have the tools and probably didn't even have any pressures to say, well, we ought to be using the tools. They weren't there. So a lot that should've been happening wasn't happening.

But I think it was-- when I went to Stanford, I had the impression that students could get access to computers fairly easily when I went there. And Berkeley. It was not like that here. It was just not-- for the average student it was a crap shoot whether they had access.

INTERVIEWER: I was 11-year-old kid. I was getting access. You could just walk in.

WILSON: You and Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. That's what they would do.

INTERVIEWER: Well, I figure they were probably sitting next to me. Little did I know I should have struck up a conversation with them.

WILSON: Absolutely.

INTERVIEWER: I was the twerp next to them.

WILSON: Right.

INTERVIEWER: So, if you could-- and I don't know if there's a way to do this-- but what were the sort of two or three fundamentally transformative ideas behind Athena? What was, at its core, so important about it?

WILSON: First, the operating system. The whole management system. There was not something we could import. People had other, certainly at Stanford and Berkeley they had systems to manage this, but the feeling was they were nowhere near as robust enough or flexible enough. I'm not an expert in this area. So I can't give you any great detail. But we probably put 60 person years at least into developing Kerberos and all of those tools. So that was one.

And the second major thing was using it for education. There was very little experimentation. Even in the hotspots here they were research-oriented-- how can I use computers to do X, or Y, or Z? But in terms of, how would I use a computer to give a student an experience with an electronic circuit, and so on, and putting circuits together? There was no, what if, try this kinds of tools. The tools were pretty slim. And they were certainly bought from outside.

There was no trading of information or data between students. The communication parts, which I don't think many people dreamed of, except the people in computer science certainly did. They were-- I was getting email way before we did Athena. But that's because Dertouzos and them put me on this list so I could do email. And my kids did email. Most students couldn't do email. So that whole social side of computers was just not here. So I think education, I think social communication, and the technology, software operating systems-- those were the key things that Athena did and that IBM and DEC wanted.

And I just have to say on the side, we had a relationship with both DEC and IBM. But Ken Olsen, who is a graduate of MIT, and who was really interested in this. I would go out and meet with him every three to six months for a couple of hours. And he just wanted to know-- we had people from DEC here full-time, six or seven of them. But he wanted to know what we were doing. And his interest-- I don't know if he saw it as a marketing think. He just saw it as something for MIT that was really important, that was going to change the way this world was here. And he had a great interest in that.

INTERVIEWER: I'm also curious to know how you got DEC and IBM to play nicely together and if that was a challenge when you talked about sort of keeping things separate.

WILSON: At first, they didn't play together. I mean it was like DEC's going to do engineering and IBM's going to do this. And any integration was going to be done by the MIT software people. But they would talk to the DEC people, of course, and the IBM people. And there was pushing. IBM or DEC, one or the other, would get unhappy that we were distributing the other guy's machines faster than their machines. And there was a lot of that. I would say, four years into it I didn't hear any more about that. And I think some of them even got on the same floor. I mean, I think they became wrapped around making Athena work, as opposed to-- there was Ed Balkovich from DEC and all them. And he was here from DEC to help, to make it work for DEC's perspective. And there was another fellow, whose name I can't remember, who wrote a book about Athena.

But when it finished, they were interested in Athena. I mean, they considered Athena a major part of their career. And they didn't think of it as DEC, Athena, or IBM anymore. And I think both sides, both IBM and DEC. the people that were here-- maybe some who got unhappy and didn't like it left-- but we ended up with a core of people who were intimately interested in it as an educational experiment and as an experiment where you're now integrating 10,000, 15,000, or 20,000 sites. And it worked out.

INTERVIEWER: So, maybe just turning to one of the other major initiatives which you've already touched on, LFM, tell me a little bit about the origins of LFM and the goals.

WILSON: Well, it was very clear that, if not actually spiritually, the country was losing it in terms of manufacturing. And we have visiting committees in every department. And I was hearing from visiting committees, some individuals very vocal that you should be doing something about manufacturing. And there was a push that we start a Department of Manufacturing, a separate department.

And so I went out and talked to a lot of people in industry, and in particular though, a guy here named Kent Bowen, who was a faculty member in materials. He was in ceramics. But he started getting interested in manufacturing. I think at the time he was starting to do things with Toyota. So he knew some of the differences. And he had an interest in that. And IBM came with a request for proposals that they would fund major manufacturing efforts at several institutions. And I, after talking to a lot of people, came to the conclusion that having a Department of Manufacturing was just the wrong thing. I mean, manufacturing-- for most of our departments, something has to be produced. If we go make it a separate department then everyone will go, oh, that's their business. It had to be integrated into design to really do it right. And that's what the Japanese do and others that were very good at it. So separating it as a department-- I got a lot of pushback on that, unhappy people from outside about that. And they would go to the administration and say we had it wrong and so on.

But, what happened was that Bowen and a group of faculty wrote a proposal in response to the IBM request for a proposal. And we had ideas about integrating management and manufacturing and technology. And our proposal was rejected flat. Rejected. Kent came back with his tail between his legs to tell me that we didn't get it. What are we going to do? And why did we lose? And we looked at some of the schools that won. And it close to forming manufacturing departments. And so we just didn't think that was the right thing for us to do. So we started talking with other faculty members. And we decided that we were going to stick to our guns and try to put together a proposal that brought the School of Engineering and the Sloan School together.

We started working on that. I've got to be careful here. And so I started talking with the dean of the Sloan School. And I was going to-- whenever you're going to do something new, people say, well I want money for more faculty. In the meantime, I decided we're not adding more faculty to this school. We couldn't afford it. There was one department where the faculty were paying for their entire phone bill for their office out of their research funds. They had used the money that was supposed to be for other things, they were using to hire faculty. So on a separate issue which we probably shouldn't get into, I said we're going to have a five percent cut in faculty. I almost went to war with one of my department heads over this.

So we were not going to do it separately. So I go to Abe Siegel and I say, we're going to do this. And he says fine, but I want six more faculty. And I say, Abe, I'm cutting the faculty in my school. I can't go make a deal where you're going to get six more. Well, that's the way it is. So I made plans to go up to Harvard. And I let it be known that I was going up to have a little talk with the dean of the school at Harvard. And Abe came and agreed. So we designed it together. And we got Kent and a faculty member in the Sloan School, Tom Magnanti. And Kent and Tom went and worked. And I would interact with them. But they basically put together a proposal. And we had an idea. What do we know about manufacturing? Who are we to write a proposal saying we're going to now teach manufacturing.

We need people that know about manufacturing. So we're going to go and find eight or ten companies to join with us. And we're going to open our kimono. They're going to have people working with us who are going to help design subjects, are going to change what we teach in subjects. So it's not going to be a matter of give us the money and we'll do it, you help us do it. And we eventually had, I think 10. But I don't know them all-- United Technologies, Chrysler, Boeing aircraft-- big companies.

And Kent and them, they wrote the proposal. I did lots of traveling with Kent raising money. And I was trying to remember the other night how much it was. I can't remember. I think it's $80 million. But it was a five-year program. We were going to develop new subjects by both the management and engineering schools, departments, that we would take students, and this shifted some, but we would take students who had a very strong interest in manufacturing. And what we had to be careful was, they were going to get a Master's degree in technology and a Master's degree from the Sloan School. There were a lot of students who said, great, I'll do this and then I'll go work for a business consulting firm. No, we want them to go to work on a manufacturing floor. Bowen and Magnanti really worked this very well. And we had all of these companies. We had a steering committee. We had people working here. And they a lot of influence. And we started producing students. And some of them went the wrong way. But a lot of them-- and over the years those students have now built a reputation for the place. And it really worked.

So it was ready for us to start the fundraising when Abe Siegel stepped down and Lester Thurow became dean. And I read in the paper that this was an idea that Lester had. Lester was good with the press. But it had happened long before that. And we learned a lot from people in industry. I'm not sure how much they learned from us. But A, we learned a lot. And B, they had a lot of influence on what was done here. It was not the MIT telling the world how to do it.

In the course of this, I began to have, during these meetings, what's the country going to do? What should the country-- what's wrong? And we had had people. Dan Roos had run a thing studying the automobile industry and so on. So we had people around that knew some of the issues. But I really thought that we ought to get all of the MIT heads together.

So I came with a proposal to John Deutch, who was the provost, that we have a study done. And I gave him a list of potential names. He argued with me about the names and insisted that I be part of the study, that I can't just pass the buck. And I agreed. But while that was all happening, later on I was told that this idea came from a member of the corporation that we do this study. And that's the way some people remember it. And I had a few people who came up to me and said, what? What? Didn't you go to them with this? Yes. Yes, I went to them. A good idea has lots of fathers, a bad idea's an orphan. And we had this thing. And Mike Dertouzos agreed. And we did a long study, we came out with a book called, Made in America, where we analyzed what was wrong.

And I just read recently that MIT, they're looking at this whole thing again under President Hockfield. And they're using that as a starting point. So Leaders is still going. I think it changed its name or something recently. But that's how it happened.

INTERVIEWER: I wanted to ask you about further developments. Clearly, the crisis in American manufacturing hasn't gone away. And what kind of evolution you saw in the program in terms of-- you've touched on this already-- but the uptake of the idea and expansion?

WILSON: I think there are several, certainly there are many universities that now have a manufacturing element. Most of them have kept it in the departments. I'm no-- I haven't looked recently and so I'm no expert on this. A lot of our problem is the difference in labor costs. I mean, I'm on several boards, one of which is building a huge facility in China. If you're going to go in China and make products for China, if you make them in the United States, you're at a terrible disadvantage in terms of cost. You've got to make them in China, in spite of a lot of the dangers of China, in terms of intellectual property, in terms of getting money back out of the country, and so on. I think, back at that time, our problem in manufacturing was not the cost of labor. It was really applying the very best technology to the process and processes in manufacturing. And I think we've learned that lesson.

So the difference today is much more labor. And I don't know how to beat that one. I mean, I have a lot of questions about this, this whole open trade that this country has. Because there are people who used to come out of high school-- and they had a high school education. And they could get a lot of jobs and those jobs are gone. And they're gone mainly because we need to pay them six, seven times what you pay them elsewhere because of our standard of living. I don't know the answer to that. If I did, believe me. I'd be famous.

But I don't know the answer to that But I think, in terms of the processes and so on, we've come a long, long way. I think the pinnacle was Toyota. It may still be the pinnacle. There are processes and they're very process-oriented. For example, Toyota-- when they put a seat into an automobile, there are specifications for the order in which you tighten the bolts to the floor and what torque. Well, what torque, fine. But the order? And you'll say, why do you pay attention to that? It seems silly.

There was a case where a lot of automobile seats were failing in terms of the way they were bolted to the floor, in terms of the way they were mounted. And Toyota could go back and know-- this is the order that it's done. And they found out that part of that failure was they should've been tightening this one first at a higher torque than that one. If there wasn't an order, if it was just whoever did it did it in a random way-- so that's called standard work. They document every little step of the way. We learned a lot about that in the interim. Not just monitoring details, but being very precise about-- as precise as you were about designing the specs on the piston and the engine, you're precise about the way you're going to manufacture and assemble it, and integrate manufacturing and design.

I don't think we're at the best, but as a country I think we've come a long, long way. MIT had some effect on that. But it was the threat, I think, of particularly Toyota, but other places. And Bowen, interesting, Bowen got so wrapped up with manufacturing and with the issue, he left MIT and went to the Harvard Business School, finished his career there teaching a lot of this stuff. And Magnanti-- the nicest story about this-- Magnanti was a faculty member from the Sloan School and we made him dean of engineering later on. So that's the strength of MIT. You got smart people-- they'll learn how to do whatever and do it very well.

INTERVIEWER: Were there other particular issues, accomplishments, or programs that you'd like to talk about from your time as dean? We've talked about LFM and Project Athena, of course.

WILSON: There were a lot of administrative things. I changed the way-- it used to be departments could just hire faculty. And then you'd find out you had a load of faculty and they weren't paying for telephones. So I was much tighter on-- they had to come to the school first and get permission to hire and make a case. They would consider that micromanaging, probably some did. But I just felt, it shouldn't be, couldn't be a free-for-all. And there were choices to be made in terms of what directions we were going in.

It is very difficult for a senior faculty member, some of them at least, to be leaving and having no one there to continue their legacy and continue doing what they're doing. If we did that for everybody, and we're going to grow into new fields, the place is going to get infinitely large. So you've got to stop doing things. And I would push hard on understanding why we needed to hire someone in this area and not always made friends. But, for example, we used to be in the microwave area in EE department. I refused to make any more appointments in microwave, not because it's bad, but just that that field has matured. We've got lots of other things we need to focus on.

So I think I brought more discipline to that. I got much more involved in understanding every promotion case. I never lost a promotion case at Academic Council. I mean, if we brought it there-- we developed a reputation. If it gets here from the School of Engineering, it's clean. There's a lot of people behind it. Did I make mistakes in promotions? I made about two or three. I could name them. I won't. But there were two or three. But overall, I think we did a good job. So we brought that.

The only other thing I would add is probably a negative thing in some ways. There's a thing called a ABET. I can't even remember what it stands for. But it's an accreditation bureau. It's part of-- whatever, I can't remember anymore. And they would come around every three or four years and you'd spend two or three days going over your educational program for them to accredit you.

And they got a hang-up on design, that the world wasn't teaching design. Now who are the people in ABET? A lot of them are people who are working in industry and do this because they're interested. Most of them are doing it for very good reasons. Some of them are people who had a professor they hated and they're going to get the academic environment, academic community back. But it's mostly people who are good-intentioned.

But they were getting to the point where the way they were judging it-- for example, we were going to have them here and I learned that the way they were going to look at design, they were going to count how many units we had of design. They were starting to be what I considered bean-counters. They weren't looking at the real educational content. They were just finding a way to come in for a couple of days and collect numbers and add up numbers. And they would get material from subjects and so on. But I thought it was a relatively superficial exercise. And there were people on the faculty-- department heads were starting to jump through hoops.

And MIT should do what MIT thinks is right. We've been a leading institution. We've been right more often than we've been wrong. And I didn't think we should be jumping through hoops. So I knew that we were respected. And so I basically told them, we're not going to bother being accredited anymore. And I talked to Paul Gray about it. He didn't stop me. If he'd told me not to do it I wouldn't have. But he knew I was doing it. And we started pushing back on that. And it started to make a lot of scraping. But ABET backed off.

And we weren't going to-- I wasn't going to have them accredit us. And that's when Paul finished being president. And Charles Vest became president. And I stayed on another term to help with the transition. But I didn't want to be dean anymore. 10 years was a good, nice run. And it was time to let someone else have fun. But they eventually went back and were accredited. But the bean-counting was changed. So I used MIT's position to push back. That's pretty much it.