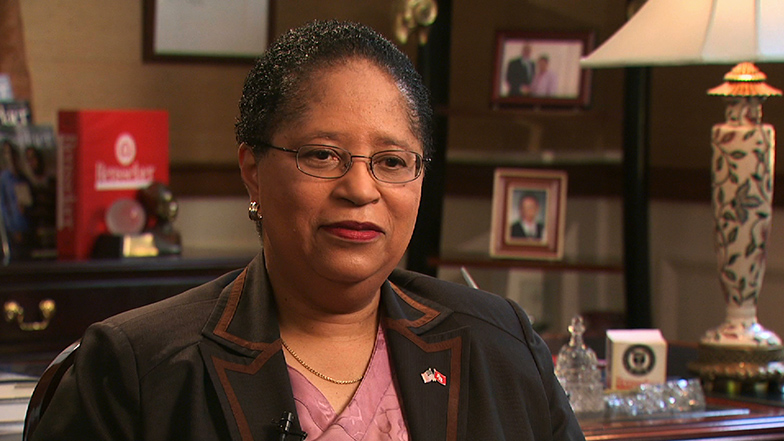

Catherine N. Stratton

iNTERVIEWER: This is the MIT 150 Oral History interview with Kay Stratton. The date is July 31, 2007. The interviewer is Brian Keegan. The interview is starting at approximately 10 AM in Mrs. Stratton's apartment.

Maybe you could tell us, where did you grow up, who your parents were, and what did they do? If you had any brothers and sisters? What were you like growing up?

STRATTON: I was born in Los Angeles, California. I lived there until I was five, and then we moved to Oakland. Then my mother died, and my father thought it was best to send me to Virginia to be brought up by his mother and sister. So I spent ages six to 21 on a farm in Virginia outside of Charlottesville. I had a very rural life, shall we say.

INTERVIEWER: This was Ivy Depot?

STRATTON: This was Ivy Depot. My education was very spotty. I went to a private school, and then when my father died when I was 10, our finances fell apart. So I was sent to a public school, a public county school, and that was a rather strange and interesting experience.

When I was 18, my aunt thought it would be wise if I learned some way of supporting myself, so I went to a Fredericksburg State Teachers College, and took what I called an enriched secretarial course. I became a dreadful secretary, but it was wonderful to get away from a farm and really experience college. So that was that.

Then after I was married, I went to Wellesley for two years. I went only for two years, and then I started my family. My education, the rest of my education was really as the chairman of the board and trustee of Lesley University, which was a delight and wonderful experience. So that really takes care of my education. I did various courses at the Radcliffe Institute, studying art and architecture, which was enormously fun for me. Alas, that really is all.

INTERVIEWER: Did you have a lot of any sort of training in art when you were growing up, or affinity to art when you were growing up?

STRATTON: No, I didn't really. I learned about art the hard way, going to galleries, talking to artists, and studying art in a very informal way. But it turned out to be, I think, one of the ways one can learn about art.

INTERVIEWER: Tell me how you met Julius.

STRATTON: Well, he was a friend of my sister. They both went over to Europe. She went to Beaux Arts in Paris, and he went on to France and later on to Switzerland to ETH, where he got his doctorate in physics. When he had finished, my sister came back first. They had become very good friends. She came down to Virginia to spend the summer there, and invited him down. So I first met him when I was 14. Then I didn't meet him again until I was 21.

INTERVIEWER: Now, he was 13 years senior. How did you meet him again when you were 21?

STRATTON: Well, he knew that I had left the farm and then gone to live with my best friend and her family in upstate New York, up the Hudson, really. He was giving a lecture to Columbia, and he invited me to dinner. It was pretty exciting dinner. Then we saw each other I guess almost every weekend, and got engaged and were married in June. We met in February and were married in June.

INTERVIEWER: What was he like back then? What struck you about him immediately?

STRATTON: I thought he was absolutely wonderful. He was very good looking. He was very interesting. It was a field that I knew absolutely nothing about. He presented an entirely different personality. I was used to dating University of Virginia boys. He was very mature, and we talked about things that I had never dreamed of before. So that was the beginning.

INTERVIEWER: Did he regale you at all with stories of his trips to the Amazon?

STRATTON: Indeed. Oh gosh, yes. When we were engaged I came up and stayed at Mrs. Jack's. Professor James was head of the naval architecture. Jay was very fond of them, and they had kind of adopted him when his mother died. So they invited me to come up, and that's when I met some of his friends and saw MIT for the first time.

INTERVIEWER: Now, why was he still single? Why was he still unattached if you was 34, then?

STRATTON: He was 13 years older than I. I was 21, and he was 34.

INTERVIEWER: Is there a reason he was still unattached?

STRATTON: He was totally unattached and was an assistant professor.

INTERVIEWER: Maybe you could tell me something about, did he have a strong relationship with his mother? I know he sent a lot of cards back from Europe when you studying there to his mother. Could you comment at all on the kind of relationship he had with his mother?

STRATTON: No, I didn't. His mother had died before I met him. All of the letters and all of the cards are in the box that I have. I haven't ever gone over them. So I never met her. She apparently was a very interesting woman who was a musician, a recognized musician in Seattle. I wish I had. His father had died before his mother. So I knew nothing of the family.

He had some relatives in Montreal, and I did go out later with him to meet the ones in Vancouver. It was a wonderful family. One of his cousins that he was very fond of was an admiral in the Canadian Navy. When his ship came into the Boston Harbor, our little girls were all invited to tea on the ship, and that was very exciting.

INTERVIEWER: What stories of Europe or Switzerland was he fond of telling or recounting? Is there any one that stood out particularly?

STRATTON: He spent a very worthwhile, interesting time in Switzerland going to ETH. He lived in a boarding house that had French, Swiss, Germans and Italians. He found it very hard not to speak-- they wanted him to speak English. He was the one American there, and he refused to. So that he had a great time with his fellow boarders. They would go off for weekends skiing in northern Italy, and they would go as far afield as the Baltics. They'd go-- I have some very lovely things from-- heavens, what's the name of the-- Bulgaria. From Bulgaria.

Later on, and I had marvelous tales of his Amazon trips with Will Ellis and his Alaska trip, on which they took sleeping bags and camped out, and found that the sleeping bags did nothing for the tundra underneath. They'd wake up with ice-cold backs every morning. So they decided after Alaska they would go to South America, which was more interesting.

INTERVIEWER: When you were married in 1935, what kind of outlook did both of you have? It was the middle of the Great Depression. What kind of career prospects did you have or did he have?

STRATTON: Fortunately, his father was a judge and had made some rather good investments. So that we really didn't suffer with the Depression as we might have. Though Jay had an aunt in Los Angeles who had purchased a great deal of property. Anyway, about the time that we moved out to Belmont from Cambridge, about that time he was made an associate professor, he went out to sell most of that property. That helped quite a lot.

INTERVIEWER: What was he working on at the time?

STRATTON: He was always working. It seems to me at that time he was working with Ed Bowles and working with Colonel Green.

INTERVIEWER: Before you came to MIT, what did you know of it, or what had you heard about MIT?

STRATTON: I hadn't heard anything about MIT until I really came here.

INTERVIEWER: What were your initial impressions?

STRATTON: When I became as a bride, I remember the one occasion. I was frightened to death. I was 21, everybody was older, everybody had children, everyone knew what to do. I was absolutely a green horn.

I remember a lovely dinner that Dr. Compton and Mrs. Compton gave me. I was so afraid that I'd be asked some questions that I didn't know the answer to. But it was a lovely dinner party.

The rest of my life for the next couple of years was getting ready to go to Wellesley. Going to Wellesley for two years. The MIT part was a tea every month at the president's house in which we wore hats, white gloves, spoke softly, quietly, and at five o'clock went home.

INTERVIEWER: What did you do at Wellesley? Was it more as a preparatory? Or for a degree?

STRATTON: I was getting ready to graduate as an historian. I was going to do the 12th century, of all of the stupid things I can think of.

INTERVIEWER: What spurred that interest in the 12th century?

STRATTON: I don't know. I must have been reading some very interesting books. I thought nobody else that I knew of was doing the 12th century. So why not?

INTERVIEWER: What was the MIT campus like back then? What struck you about the architecture? Or the general atmosphere, the people walking about?

STRATTON: Everyone was much more formally dressed, naturally.

STRATTON: It was much, much smaller. The buildings, I thought, were very stark. As Jay's career progressed, and when he became president, it was very obvious that the thing that I wanted to do was to bring art to the campus.

INTERVIEWER: You already mentioned that you had a dinner with President Compton at the time. What struck you about him when you met him? What was his personality like?

STRATTON: I thought he was lovely and kind. He had wonderfully sharp eyes, so that you knew what was going on behind those eyes all the time. Mrs. Compton was a beautiful example of a president's wife. Gracious and kind and loving and very bright.

INTERVIEWER: Did you meet Vannevar Bush or any other members of the higher administration?

STRATTON: I certainly did. When Jay would come home at night, we would always sit and have a quiet drink together. He would go over what he had done during the day, which was enormously interesting to me. We did quite a lot of entertaining, even as he went up. The thing that's always struck me and made me a little cross was that the gentlemen would always gather together and talk about the fascinating things that they were doing, and the ladies would gather around here and talk about their children and schools and maids and whatnot, which didn't seem to be quite as interesting.

INTERVIEWER: What was the student body like at the time? It was obviously very male.

STRATTON: The student body was very male. The undergraduates were, as I said, always dressed in ties and jackets. Professors exactly the same. It was the beginning of the graduate school that was increasing.

It was Karl Compton who really changed the Institute, I think, from being a technical school to broadening it in the sciences. Jay was very much a part of a small committee-- and I can't remember what the small committee was called-- but it had the huge influence on broadening the Institute. There were five people in this committee. He was one.

I think it's very important to put this in, because it began to show that Jay was bringing back some of the science and some of the work that was being done in Europe at that time. In atomic energy and all of the basic things that we now have to learn in order to do anything in electromagnetic theory.

It was a period from 1918, maybe earlier, that there was a real rebirth of science in Europe. But if you would find out what that committee of five was, it's very important.

INTERVIEWER: Among the students or the faculty, was there a reaction that you would get if you had mentioned the idea that women might become members of the faculty or the student body? Or was that wholly dismissed out of hand?

STRATTON: That came a little later. There were proponents and people who thought that the Institute should be for men. Jay was one of the people who promoted the idea of feminism. By the time he got to be president, the number of women had increased an enormous number.

INTERVIEWER: What were the expectations of the spouse, of the wife of a faculty member? What expectations did you have serving on committees or organizing things with other wives?

STRATTON: Well, one of the things that I'm very proud of, really, is when I came as a bride, the Women's League was called The Matrons. And The Matrons did I guess, good things. When we graduate, when I-- I'm trying to think whether it was when Jay became provost or not-- there appeared in the Matrons a number of very, very able women. There were women who could have had careers of their own, but stayed with their husbands to support them.

That was when The Matrons were regenerated into the Women's League and expanded into all of the interest groups. They would, for instance, the-- trying to think what it was called-- the Draper Lab was incorporated, and so that broadened the Women's League. What we were trying to do was to make it warm and friendly and inclusive and give women the chance to start a furniture exchange, a school for the kids, flower groups, all kinds of interest groups developed. We also developed a structure for the Women's League and produced an ongoing organization with infrastructure. So I was very pleased to be part of that. Among the leaders of that time were Kay Bolt and Dolly Bryant, both of whom I worked with particularly.

INTERVIEWER: Well, I hope to come back to that in a little bit.

STRATTON: I know I'm shifting around terribly.

INTERVIEWER: It's OK.

So when you came in 1935, where did you live?

STRATTON: We lived at 994 Memorial Drive in a lovely apartment on the seventh floor. I couldn't bear to look way down and see all the things growing down there. I said to Jay, "I've just got to get my hands in the dirt."

So we moved out to Belmont. Up on the hill, they were just starting to develop. There were a lot of holes in the ground that would become beautiful homes. We found one that was just being finished at 108 Rutledge Road, and we decided to buy it. That is the site. That's when we decided that it was a beautiful home. It had enough rooms for the children that we were planning, after I finished Wellesley.

I never finished Wellesley. I started the children first.

Belmont was a perfectly beautiful community to raise children safely. So that they could have bicycles and tricycles and knew all their friends within blocks, and that kind of thing.

INTERVIEWER: When you came into Cambridge with Julius and you would go out into the city or into central or Harvard Square, what were the neighborhoods like? How were they different than as they are now?

STRATTON: When we came in, it seemed to me that the faculty was becoming very dispersed. One of the things we wanted to do was to have dinner parties and bring in the heads of departments and the new people. ( one of the trustees-- and this was while Jay was president-- gave us really, quite a lovely lump sum that I could give to the heads of the departments so that they could entertain their new people.)

It seemed to me that we were getting very disparate and that we needed to bring MIT closer together. That worked, that worked quite well. I got to know a lot of department heads in there, and the new people, through supper parties that we had. I always had large tags on, and I would say, I'm glad to meet you. Do come in. I'm Kay Stratton. They would say, "I know." Without giving me their names. So it was a little-- I'm very bad on names and dates, anyway. So you'll have to check all of this.

INTERVIEWER: Now, when the hostilities started in Europe in September of 1939, was there a sense among your friends or you and Dr. Stratton that we would become involved eventually? Especially after the attack on Pearl Harbor, was there a sense of the role that MIT would take on the world stage?

STRATTON: There certainly was. Because he was head of RLE. Stark Draper was very important, as you know. We have one of his original-- what do you call it that-- essentially guidance systems. We saw a lot of the shakers and dealers, and had a lot them to dinner.

INTERVIEWER: Did you know then, did Julius receive any calls from Washington or anything saying, here's what we need?

STRATTON: Yes, he spent quite a lot of time in Washington. He was the Science Adviser to the Secretary of War. It seemed to me he was always gone whenever I had any problem with the children.

I think he enjoyed-- I think he learned a huge amount of dealing with administration in his Washington time. It certainly paid off when we left MIT and he was at the Ford Foundation, because he gave one day a week to Washington.

INTERVIEWER: By this time you'd had children already. How many children?

STRATTON: I had three children. Two of them are there, they are both in London. One of them is in Newburyport. The elder one has just received an award, a commander of the British Empire. So that was rather fun. I'm skipping so badly, I don't know how you'll ever put any of this together.

INTERVIEWER: What changes or what sacrifices did you have to make with regard to rationing? Was this unduly difficult during the war?

STRATTON: Yes, it was difficult during the war. I worked in a tomato factory, putting up tomatoes. I also put up meats, which didn't last. That was a disappointment. I had a sister who was captain in the Army, and she would save up all of her coupons so that we had a royal feast when she came home.

The war effort was very serious. I dug up my front yard in Belmont and grew vegetables. We were all very conscious of the war.

INTERVIEWER: Did you ever have the chance to visit the radiation laboratory? Or was but all shut-off to outsiders?

STRATTON: It was shut-off to outsiders. I never really got to look around at all of the exciting things. I went to all their parties. The radiation lab had the most creative people. We used to put on shows, and I think all of the music still exists. So I took part in all of that. That was fun.

INTERVIEWER: Who did you meet at the parties, or through Julius, from the radiation laboratory?

STRATTON: Yes. We went to parties. Stark Draper and his wife Ivy had marvelous parties. I'm afraid that we all wobbled out. They were super parties.

INTERVIEWER: After the war, the Lewis Committee, a committee on academic survey, was convened. Julius participated in that. It had fairly wide ranging, even still today, impact on the curriculum, the undergraduate curriculum at MIT.

STRATTON: I wonder if that's the committee I'm talking about.

INTERVIEWER: Well, this was in 1947, 1948.

STRATTON: That's too early. So there must have been another commission. That must have been the time when they decided about the women.

INTERVIEWER: OK. Did you have any thoughts then on reform in the undergraduate curriculum? Because it was notable in that it emphasized the development of arts and humanities by the creating its own school. Were you whispering sweet nothings into Julius' ear? Or did he come home and talk about the changes that were afoot.

STRATTON: Well, yes. We did talk about it. But it was in 1960, when we moved into the president's house, that I formed a committee, the Art Committee, which would come about under Wiesner. I'm very proud of that, because I'm still a member of the Council for the Arts. It has become, I think, a counter balance.

If I had to make a comment on the curriculum, I would say that we needed more emphasis on the arts. It's the only thing that counter balances the rest of the Institute. It has always seemed to me that you could be an excellent engineer and put something across, but if you wanted to be beautiful, if you wanted to be a beautiful bridge, you had to have a background in the arts and humanities.

INTERVIEWER: Did you have any memories of the mid-century convocation when Churchill came to speak? Maybe you could tell us what that was like.

STRATTON: Yes. That was one of the highlights, I would think, of our career. It was the first time that I had to arrange an enormous dinner for 500 people. I adore cooking. I cooked from the time I was six years old. I was very proud of the menu too. Because we had-- well, you've got the menu, so there's no point in going into it.

I remember dressing to the hilt and wearing a strapless gown. As I went up the stairs, someone stepped on my train and I grabbed-- it came out all right, but it is a moment that I remember.

The convocation was very exciting. I remember taking the speakers to the airport with all of the police going ahead and behind, and the sirens blowing and so forth. Seeing them off.

INTERVIEWER: What was Churchill like as a speaker?

STRATTON: Well, I saw very little of Churchill, because he stayed at the Ritz with his cigars and brandy and his speech-making. So I met Mrs. Churchill, and I thought, how exciting. I'm terribly interested in foreign policy, so I thought, this is the time I can ask her a question. She sat down on the sofa next to me, and before I could open my mouth, she said, my dear, how many children do you have? So that really cut off the rest of the conversation. Or directed the rest of the conversation.

INTERVIEWER: Killian gave a speech, as well. Do you have any memory of what he spoke about? Or the general tone of the event was like? The speeches centered on?

STRATTON: No, I don't think I do. At 93, it's very hard to remember things.

INTERVIEWER: Julius became provost in 1949 and vice president in 1951 and chancellor in 1956. He rose through the ranks quite rapidly. How did your responsibilities change with all of his promotions? What kind of traditional roles or new roles did you have to take on?

STRATTON: Well, a lot more entertaining. I remember-- I know you maybe didn't remember Margaret MacVicar, but she was one of the graduate students who lived across the river. Mrs. McCormick had given the women over there a nice sum so that every time it rained they could come by taxi, which I though was nice. Anyway, when we were in the president's house, they would come occasionally and sit around the fire-- and I remember Margaret MacVicar was one of them-- and talk about the problems that the women students had, which made me a kind of part of it.

I also had to do with student housing, which was interesting. So in the evening, as I said, we would discuss all of the things that were going on that I could help with. I had a wonderful secretary, and we would work all day until I had an appointment. I would take notes and she would transcribe them and file.

So it was a busy, busy life. It's the only time in my life that I have not kept a diary. Every single trip we took is written down. Most of them are typed.

INTERVIEWER: Did you meet other wives who had professional careers? Or who were in academia?

STRATTON: I didn't know the women professors very well. I don't know them very well now. I know the head of architecture, and work with her. I worked with Alan Brody, who is assistant provost for the Arts; and I worked with Jerry Wiesner on the arts.

After Jay retired, we went to New York for seven years, six years. That was the first time I was really free and I just didn't have to go to any committee meetings. I joined the National YWCA, and became a trustee at Bank Street College. It was a new life.

INTERVIEWER: You mentioned that you would often meet with the students, or the women graduate students like Margaret MacVicar What concerns did they have that they expressed to you? What were the problems they were facing?

STRATTON: What were their problems? I think being minority students in an atmosphere that wasn't attuned to women, that was that of them. There were a lot of clubs and so forth that were all men. I think now they're equally invited to take part in all of the things.

INTERVIEWER: I'm going to feign ignorance, and maybe you can tell me who is Katherine Dexter McCormick? Did you ever meet her?

STRATTON: Oh, indeed I did. Jay had a lot to do with her. I remember we were invited to tea at Mrs. McCormick's over on Beacon Street, and-- I don't know whether it was then or whether it was with Jim Killian-- that she promised to build the women's dormitories. Betsy Beckwith, who was an architect and part of the team of Beckwith, Haible and somebody else, she was, I think, the inventive part of it. She designed the two women's dorms.

INTERVIEWER: Maybe could tell me, since I'm feigning ignorance, like who Mrs. McCormick was.

STRATTON: Well, I really didn't know her very well. She went to symphony every Friday afternoon and she would walk home. She always wore black stockings, and they had a tendency to slip down. She always wore black, and you could always identify her. I never really got to know her. Jay did, but I didn't.

INTERVIEWER: Jay was also offered several positions at that other universities and outside companies. Why did he stay at MIT? What kept him here before he was president?

STRATTON: I think that every day was a new excitement. He couldn't contemplate-- I remember the first time he was offered the presidency of one of the academy that teaches people to be sailors.

INTERVIEWER: The Maritime?

STRATTON: Maritime. I thought, oh, how exciting. Why not? He said, leave MIT?

Everything was burgeoning. Everything was exciting. He was deep his book on electrical magnetic theory. He loved teaching. So that what with one thing and another, it was ridiculous to even think of another job.

INTERVIEWER: What hand did you have in any decisions of-- did you want him to go somewhere else? Spread his wings somewhere? Or was he so set on staying here?

STRATTON: I remember one time he was invited to go to Pittsburgh. They sent up a plane and the head of their trustees. It was the first time I was comfortable in a plane. When we got there, of course we were entertained. Enormously. It seemed like a terribly nice place. But when we came back, Jay said, "It can't compare to MIT." So that was that.

INTERVIEWER: In all of your entertaining and various activities and committees that you've participated in, did the disparity in your ages-- between you and Jay's age-- ever come up? Or was that ever an issue, the fact that you were so much younger? Or so much younger than even his other peers' wives?

STRATTON: I don't think it was after the first two years, in which all of his friends had little children. I had so little in common with them that it was a little difficult.

INTERVIEWER: Maybe could tell me about in the early 1950's with the McCarthy Hearings. Did the tendrils of that ever kind of reach into your lives?

STRATTON: It did. It reached into our lives because-- and I don't want to name names-- but one of the professors was given a very hard time by McCarthy. Jay stood up for him absolutely. It all passed over. As a result, I think that the professor was grateful to Jay all of his life.

When we left, he said he wanted to give Jay a gift. So Jay said, "Well, you choose it. You know more about art." So I chose a lovely, modest little painting. And the painter said, "No, that isn't what I mean at all." So he gave that painting to us.

I think you can see a symbol of his past in the Nazi difficulty. He was a very free-wheeling, lovely, lovely person. It was very hard for him; but it all worked out.

INTERVIEWER: I noticed in reviewing the notebooks you kept, the social notebooks-- you kept such meticulous notes of all the menus and the drinks that were ordered. It certainly seems that the times have since changed in that there was such a presence of alcohol, I guess. Did guests often become well-lubricated? Were these raucous events?

STRATTON: No, never. I have people in at least once a week now for wine and cheese. People from, hopefully, all over the Institute, so I can know what's going on. With a walker, it's very, very difficult to go to the lectures that I have always gone to.

I have a series, as you know, of two a year: one on health, and one on foreign policy. I've just been finishing up the one on foreign policy, domestic policy, which is going to be, How Green is MIT? Which I think will be fun. I've got marvelous, marvelous panelists. The one on health has gone on for 20 years now. So that's fun, too. It keeps me fairly busy.

INTERVIEWER: Maybe you could tell me what the Technology Matrons' Board was. You mentioned this earlier, that there's this committee of women that predated the Dames' Board. Were the Dames' Board and the Matrons' Board the same thing?

STRATTON: The Matrons' Board became the Women's League. The Matrons' Board was the one that shifted the mission from being a social thing to being one of work and inclusiveness. And really, production. We give $50,000 a year for a scholarship. Is that what you meant?

INTERVIEWER: Well, I was hoping you could tell me-- you mentioned you worked with Mrs. Bolt -- I guess you could tell me how you got involved with the Matrons' Board.

STRATTON: Well, we would have meetings constantly and I would go over as a member. I also worked during the war doing bandages. I don't remember very much, except that we were very diligent for three hours in the Emma Rogers room rolling bandages.

INTERVIEWER: What was the Faculty Environment Committee?

STRATTON: I don't remember one.

INTERVIEWER: It was to welcome new faculty, I remember. It's probably between 1959 and 1962 to welcome new faculty to the campus.

STRATTON: Oh. Well, there is always a tea. We always had a tea ceremony to welcome the new members, and to explain what was available to them. That was fun. Now I think they set up tables so that a new person can wander around and sign up for anything that they're interested in, from dinner at foreign places to anything they want to do-- bird watching, walking, flower arrangement, et cetera.

Do you have a catalog of the Women's League?

INTERVIEWER: I've seen one.

STRATTON: That gives you-- there's something like 15 or 16 things that you can do if you have time.

I'm also working with the graduate student department. The third in command is Barrie Gleason. Barrie Gleason has really developed a program for the graduate wives and family, and an art project for them and so forth.

INTERVIEWER: Jay was named an interim president of MIT when Killian left for Washington. He was the vice president at the time, or the chancellor. It was sort of an obvious promotion, but what was your reaction, or his reaction?

STRATTON: I don't think there wasn't any. Because when we came in, we went up to the penthouse up on 100 Memorial Drive. We had help, and the girls had an apartment downstairs and their own entrance and their own telephone, which we corrected later. Mrs. Stratton got a great many telephone calls. So when we were at the president's house, they all had chose their bedrooms on the back of the house so that they were opposite Senior House. It was some communication.

[LAUGHING]

INTERVIEWER: Jay then became the president of MIT in 1959, right? That was obviously a permanent basis until he retired in 1966. What was your reaction to his kind of new responsibility, new burden he had to bear, and you had to bear, as well?

STRATTON: My concern was that nothing had been done to the president's house since the first Stratton, who was a bachelor. Everyone wanted to know whether Dr. Stratton was my husband's father. No, he wasn't. No relation, whatever.

It took us-- Betsy and I-- it took us a whole year to reconstruct the president's house. We added two rooms to the basement. We re-did the living room completely. Those were the principal things that we did. It took an entire year.

The last thing that came in was a carpet that we had made in Puerto Rico. Every day, we called up because it was late in coming. We had the freshman reception due, and it came two days before. So we all had a sigh of relief as it got rolled down. As always, someone comes an hour early to any reception. I don't know whether they get the time wrong or not--

[BREAK IN AUDIO]

--to know that you dressed and were down and ready an hour early for the first guest.

INTERVIEWER: So you had just renovated the president's house. You mentioned that you put in some new rooms. Did you bring in any art work? What was the existing state of the aesthetics, or the art in general?

STRATTON: There was nothing down there. There were, I think, two objects. So I went to Bill. He has a whole gallery in the MFA. He said, "Come out and choose anything you want." So I went out with the two girls, and we chose absolutely the most wonderful art.

The period that I'm most interested in and know most about is from 1850 French until 1925 American. We really had an exhibition. It was wonderful.

We also got a loan from the MFA. Jay was made a trustee. I don't know how that worked, but we had one in the dining room, which was lovely, from the MFA.

INTERVIEWER: So you lived in the president's house. What was it like to live there?

STRATTON: It was wonderful. It was absolutely wonderful. We changed the living room so that the fireplace, which was at that end, was in the middle of this. We had a lovely sofa. Every day at 6:30 he came in, and the butler brought us hors d'oeuvres and our drinks, and we sat and just worked over the world for an hour before dinner.

INTERVIEWER: What was it like to raise a family in the president's house? What age were your daughters by that time?

STRATTON: They went to a private school. I had a graduate student who took them up to Buckingham every morning and got them home every night. They brought their friends home. They also brought them home when we were away, and had probably a freer time. But they always came down and met people at parties and passed hors d'oeuvre and enjoyed all of the really famous people who came. All the astronauts and Kitty Carlisle Hart, and all of the great music people who came to the house for a reception. It was fun.

Laurie had a pet raccoon, which he used to come down on her shoulder. I'm not sure that people didn't back away, but Stark Draper and his team had made her a house, which was kept up on the top floor in the rec room. Rec room is the right word. So the rec room was there for quite a while. Then he escaped into the pipes at MIT. When the police finally found him, he was very emaciated and half dead, so they took him out into the woods and let him go.

INTERVIEWER: At the time that you were in the president's house, the MIT students had a fondness for pranks, for hacking. Was the house ever a target for these pranks?

STRATTON: We were lucky, lucky, lucky. The only hack-- and it wasn't a hack-- was when they came outside and stood in a chorus and said, "$1,700 is too damn much!" This is when they had raised the tuition. Can you imagine? What is it now? $48,000? $47,000?

INTERVIEWER: Tuition alone is probably near $40,000.

Did you ever have a chance to meet or talk with John Burchard and his wife? What kind of conversations did you have with him?

STRATTON: Oh, yes. We were very close friends. They lived out in the country; and they were both marvelous cooks. We would go out there for a wonderful dinner with very interesting friends. John Burchard was the person who gave us the first money that the Art Committee had to spend on sculpture. He was a good friend; and my goodness, he was able.

Did he write a book?

INTERVIEWER: He may have. I don't recall.

STRATTON: The early book of our period at MIT was written by, trying to think of his name, and he put all of his notes in a big box on his desk. The person who was sweeping his office thought the box was to be thrown away, and threw it away. But the book still exists. So it's a good resource.

INTERVIEWER: What of Elting Morison?

STRATTON: Elting Morison was a wonderful friend, too. We were very disappointed when he went to Yale. His wife, whom he divorced, was a great friend, also, for a long time.

INTERVIEWER: So you were involved, in a very large sense, in the planning for MIT's 100th anniversary in 1961. What kind of events were planned for that week?

STRATTON: Oh, gosh. Simply remember what I told you about the dinner and the guests. I had to plan the dinner for MacMillan. So that must have been mid-century. Was that mid-century when MacMillan was here?

INTERVIEWER: Maybe.

STRATTON: I remember the person who was my great helper and planner was Miles Cowan. He and I worked over that dinner and those place cards. Every few hours they would change. They would say, "This person can't come, but this person can come." So we were just doing that all day.

The house always had to be filled with flowers, and that was one of my jobs. One of the people that I called on to help me was Carol Brooks. Carol Brooks. She was the wife of Penn Brooks, who was the first dean of the Sloan School. She was not only a lovely person, but she had won national prizes, all over. So we met at least once a week to do flowers for the president's house. We called on Endicott House to help us send in bouquets.

INTERVIEWER: In the archives there's a letter from Sophia of Greece. She sent a tersely worded letter. Do you remember that at all?

STRATTON: I do. I have her photograph in a silver frame. In the book, Stratton Years, you will find a description of that day.

INTERVIEWER: Now the centennial happened in April of 1961. That was also the same month the Soviets launched their man into space. Was MIT's celebration at all overshadowed by that?

STRATTON: Well, I happened to be down in Jamaica. Every year one of our trustees, Alfred Loomis, and his wife invited us to Jamaica for a week. We were having a picnic. Anyway, that was where we were, and we were listening to the radio. That's where we were when that happened. It was pretty exciting.

INTERVIEWER: Did you and Jay still travel a lot?

STRATTON: We have traveled a lot.

INTERVIEWER: Where were some of the places you traveled after the war? STRATTON: After the war we went, I remember, we went to Mexico to the fiesta every year. That was lots of fun. A different place in Mexico. That was very broadening. We went to visit alumni all over the country, and really, quite all over the world. We went to China and Japan. A lot of this, we went after we left MIT and Jay became chair of the Ford Foundation. All of my diaries, which are now being sorted out and will become put in a book, will give you an account of a lot of that.