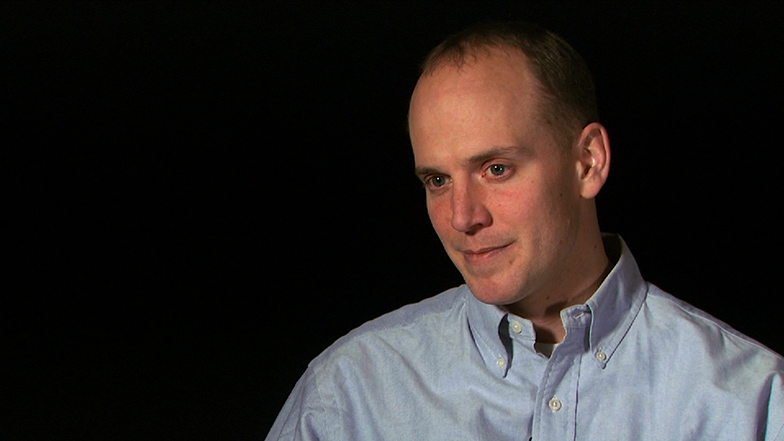

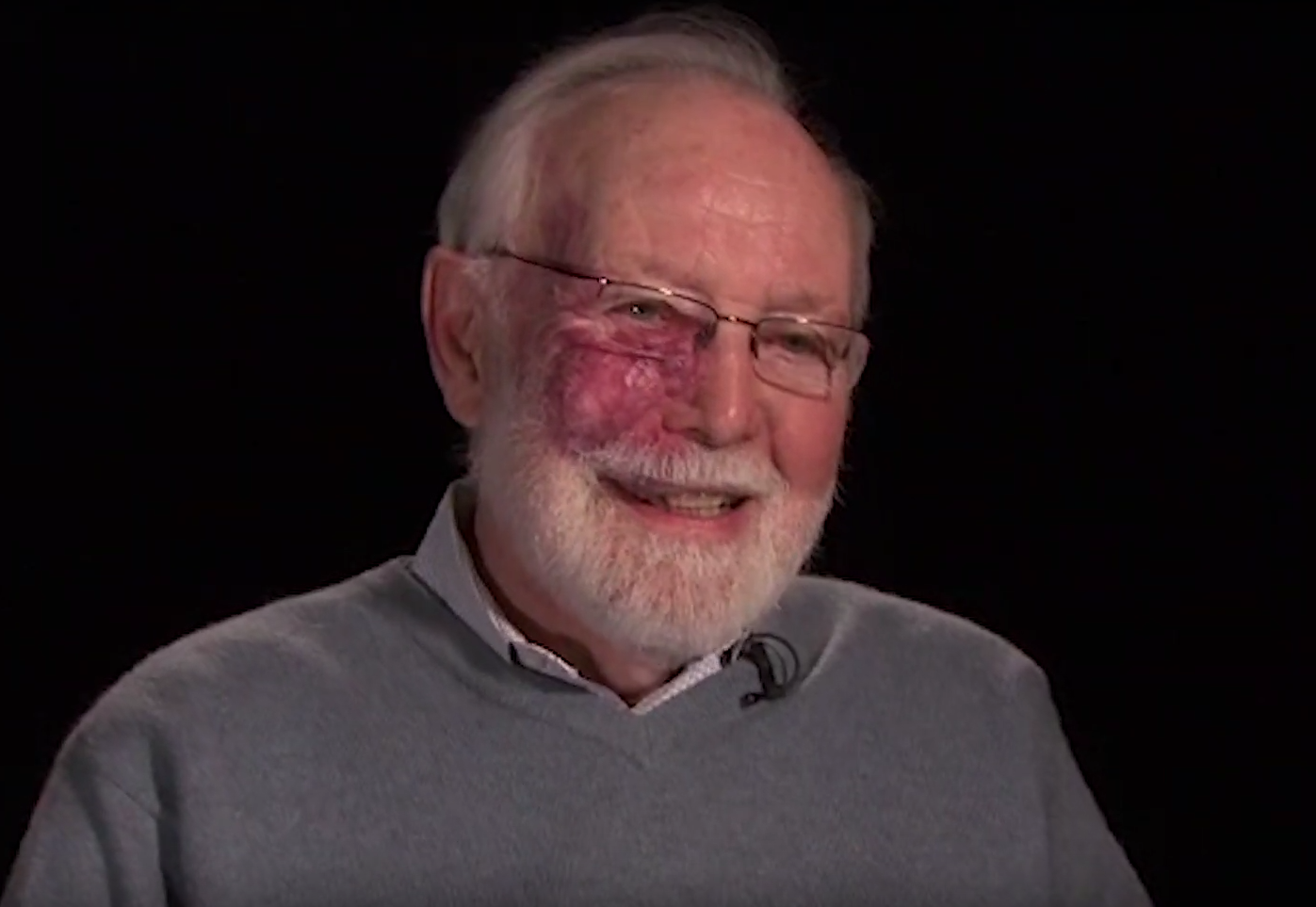

Robert M. Fano ’41, ScD ’47

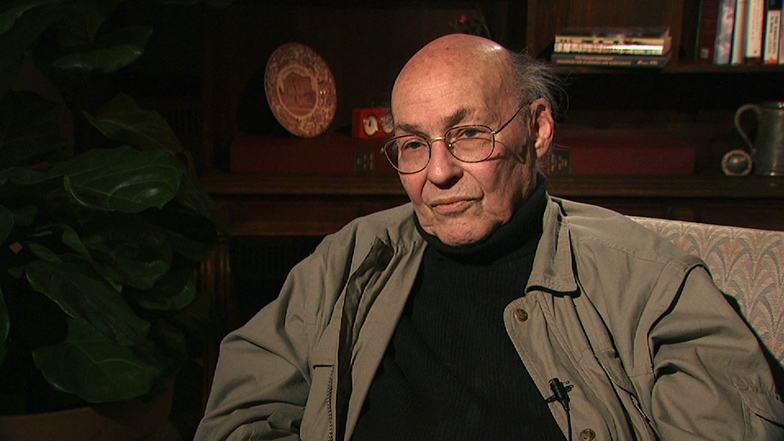

INTERVIEWER: So this is the Infinite History interview with professor Robert Fano. I guess I'd like to start by asking you where you were born and where you grew up?

FANO: I was born in Torino, Italy on November 11, 1917, exactly one year before the end of World War I. And I was raised there. I left Torino in 1939 when I was still 21. And I landed in New York in November-- no, October '39. I'm sorry, I said I left in '39, but not till the end.

INTERVIEWER: Tell me a little bit about your family.

FANO: Yeah. Well, my father was a professor of mathematics at University of Torino. And my mother, she was a paintress mainly, although she stopped painting when I was perhaps five. I remember, barely, going in the country for her to paint with her and carrying the seat. You know, the folding seat. But then she stopped. I have a lot of paintings here and my family has quite a few oil paintings.

INTERVIEWER: Is there anything about your time in Italy that you think has been influential in terms of your career path?

FANO: I would not say that. I always wanted to be an electrical engineer, for reasons that I don't remember. And I also knew that I didn't want to be a professor, because spending the day behind the desk, as my father was doing, was not anything that appealed to me at that age. I was right in one and wrong in the other. It will come out why.

INTERVIEWER: Where did you do your undergraduate studies?

FANO: Well, I worked for four years in the school of engineering called Politecnico in Torino. But there it was a five year program, so I did not finish the degree. It was a broader scope program than common in the United States. But however, the last year was a specialization year, which I didn't do and so I had to do it here.

INTERVIEWER: So what made you decide to come to the United States in 1939?

FANO: My family's Jewish and the racist law of Mussolini came out. The first statement, there was a committee that decided there was something called an Italian race and Jews were not part of it, which was the beginning. That, I think, was something like June 1938. But in November the laws came out and we had to put a lot of restriction. And at that point my family, with the exception of my father, was time to decide to go.

INTERVIEWER: And your father?

FANO: Well, we persuaded my father to move too.

INTERVIEWER: So you all got out?

FANO: We all got out. Yes.

INTERVIEWER: You were lucky.

FANO: Well, my older brother and I came here. My father and mother spent the wartime in Switzerland. And then of course we got together again after the war. So that's why. Basically there was a family emergency reunion, on my birthday as a matter of fact-- November 17 in our country home near Verona. And basically we decided that we had to scramble, because that war was coming and God only knows what's going to happen.

INTERVIEWER: What brought you to MIT?

FANO: Well, when I arrived in United States I had to decide to finish my education, so I applied to various schools. I did not apply to MIT at first, because I didn't think I had a chance of being admitted. And my sister-in-law-- which besides being my sister-in-law came from a family that was very close to my mother-- she said a sure way of not being admitted is not to apply. So I applied. And as a matter of fact, MIT was the first school that replied and admitted me. And it made the best use of what I had learned in Italy.

So in January 1940 I came to Boston to visit to discuss the details. And I don't know what is the policy now, but at that time the policy was very easy about giving credit for courses taken elsewhere, unless you showed later that you really didn't know the material and then you had to go back. So I came. So in February 1940 I arrived in Boston. And I started my schooling here.

INTERVIEWER: Do you remember any of your first impressions of MIT? Of the students or the campus?

FANO: Yeah. Well, it's a very different educational system. And I appreciated it very much because the contact with faculty was easy, while in Italy it wasn't at all. Among other things, you didn't have a chance to see the faculty unless they had a laboratory, because the professor didn't have an office. My father had an office because he was the director of the mathematical library. So there was an office, but otherwise they don't. A very different educational system, and I very much appreciated what I got here.

INTERVIEWER: What made you decide to stay at MIT for your DS degree?

FANO: Well, I did decide then. I finished the degree requirement in February 1941. And of course I went through many interviews and I had a lot of offers. But then when they asked, then they had to withdraw it. And the reason was, something that I did not realize, is that the entire electrical industry was already on a war footing. And they all required military clearance, which I could not get as an Italian citizen. And there was only one offer that didn't require it, and that was from General Motors official body plant in Michigan-- Grand Rapids, Michigan. So I took that offer.

Actually, what had happened-- which is important for what follows-- is that Professor Carlton Tucker, who was the executive officer of the department, asked me in February whether I was interested in a teaching assistantship. And I said no, because my interest was to go out in industry. Not only, but at that point the financial future was kind of cloudy and I wanted a job. But that was a horrible job. I went there, I stayed six months, and I came for graduation in June to MIT, and I went to see Professor Tucker. And I told him that I had changed my mind. And what happened then is that the day after registration day at MIT I got a wire from him offering me the job of teaching assistant. So the next day I jumped in the car that I had bought, a Chevrolet. You know, in those days Chevrolet was one car. You had a choice of colors, but that's all. And I drove to Boston. And I've not moved since.

INTERVIEWER: So you don't remember what it was about electrical engineering--

FANO: No, I don't. I just don't remember. I had an uncle who was a mechanical engineer and I had a grandfather, maternal grandfather who was also an engineer who was working on railroads at that time. But why electrical engineer? I don't remember.

INTERVIEWER: When you were small did you build things a lot?

FANO: That was very unusual in Italy to do anything like that. Tinker Toys, it was called Meccano, which was available here too, that you build things. But nothing electrical. I know a great thing is when I got an electrical board to do [INAUDIBLE] stuff. I mean engineering interest was there. But why actually electrical, I don't know.

INTERVIEWER: When you took the job as the teaching assistant, is that when you also began your study for your DS degree?

FANO: Well, no. Let me explain. It's similar today still. A teaching assistant is given half time for graduate studies. And the idea then is that if you stayed as a teaching assistant for two years, you would complete the requirement for a master's degree. That was the idea. Actually, things work out very differently because in November-- December 11 everything changed. The first term I was grading quizzes all the time, which is kind of boring, but was so much better than working in that plant. You have no idea what-- the ignorance, technical interest in that plant was just unbelievable.

INTERVIEWER: What was your job? What were you doing there?

FANO: I was supposed to be a student engineer. I was a maintenance man on the welding presses. There were two huge welding presses. And I had rewired the machine among other things, but there were only two graduate engineers, senior except the people my age. One was the personnel director and the other one was the chief electrical engineer. And you should have seen his knowledge. He was a-- I won't go into detail because you wouldn't understand. If I tell you that the whole plant was ungrounded. Not grounded. Do you know what that means?

INTERVIEWER: I know what that means.

FANO: OK. And I found out by accident because one day things were not working and I started making measurements all over to find out what it was. And strange figures of voltage appear everywhere. It's because the whole electrical system was floating. I can't go on. I won't bother you with that. So basically I got back because of that.

And the first term was sort of boring. The second term I was given an assignment to be the laboratory instructor in the measurement laboratory. And that was very interesting. And one more thing, I was very lucky to have some very bright students. One of them was Dick Adler, who became a professor here as well as a personal friend. And unfortunately died rather young, because he was hit by a car in Concord jogging in the morning. At that time he was associate department head in the department. And then there were the [Libbell?] twins that went to Stanford. We kind of filled the faculty at Stanford with our students.

INTERVIEWER: I don't think they'd probably want to admit that.

FANO: Yeah. Why?

INTERVIEWER: Well, they probably would prefer to think that they're training their own.

FANO: No. I mean they got their doctorate here. That's what I mean, eventually. And so did Dick. Well I mean the head of the electrical engineering department at Stanford got his doctorate at MIT also, way back.

That was my second term here. But by then we were at war. And what happened, which was very interesting and useful to me in a sense, a lot of the faculty left for war work in there. So I and all the teaching assistants were given teaching duties that were unheard of. The first teaching duty was for-- what was it? Electronics for Communication Engineers. For communication. Well, I was given a chance the preceding term to listen to the class, so I knew what it was. But after that I was given assignments to things that I had never taught before. Oh yeah, it was really an exceptional situation that did a lot of good to me. And by '44-- no, by '43 I was promoted to instructor, which at that time was a faculty appointment. In other words, I was a member of the faculty. As a matter of fact, one of the members, a member of the faculty when Jim Killian became president.

And then that year I was called in by my mentor, Ernie Guillemin, and said, how about teaching a course on microwaves and antennae next year? And I said, well, I'm interested in that subject, but I know nothing. So he gave me the story of how he became involved in circuit theory, and after that I had to say OK. So I did it. I taught all sorts of courses. But that result was that I didn't have any time to do studying, to take classes. So I never got a Master's degree as a result.

INTERVIEWER: But you got a DS?

FANO: Later on.

INTERVIEWER: Later on?

FANO: Yeah. Well, it came in 1944. Italy was out of the war. And I could get the military clearance. And that's when I went to the Radiation Laboratory.

INTERVIEWER: So can you tell me a little bit about the work at the Radiation Laboratory?

FANO: Well, I was what they called a microwave plumber. I was designing microwave components. And I designed various of those. Well, that was also a great opportunity. The Radiation Laboratory was full of physicists. Now, whether the fact that my older brother, five years older than me, was a physicist, it probably helped when I got to know a lot of them. It was a good experience there.

INTERVIEWER: How did you come to get interested in information theory?

FANO: That's another story. That comes later. Well, you see, the Radiation Laboratory essentially started demobilizing right at the end of the war. But I was writing a chapter-- actually, two chapters together with somebody else-- of one of the Radiation Laboratory books. So I worked on that until spring '46. And then I was appointed research associate in the department and became again a graduate student. And at the same time I started teaching my old graduate course. And that was in April of '46.

So you see, the Radiation Laboratory, most of the work that I was doing was trying to design component and broadband. I don't know whether you know what I mean by it. You do? Yeah. OK. And the question came to my mind all the time, is there a limit to doing that? And so I picked that as part of my doctorate thesis. Well, it was not in microwave, but in generally lumped element circuits.

Well, that was in April '46 and I got nowhere until close to Christmas. And then, when I was walking from my apartment on Beacon Street to Back Bay to go for Christmas at my brother's, I saw the light. And then it was a matter of doing some work, and there was my thesis done.

INTERVIEWER: What was the idea that came to you?

FANO: That's really tricky. I won't go into that. It was, in a particular situation in which the problem was solved by-- oh, what is the name? Doctor? Bell Laboratory. We'll come back. You see that's what happens to me. And I saw that result in a different light that he did. And then I could generalize it completely. And as a matter of fact, I worked on that in the spring and I went to the Institute of Radio Engineers annual meeting in New York and I looked for him. And the name will come. And asked him whether he had done any more-- I had lunch with him-- whether he had done more work on that. And he said no, and he offered me a job.

So that's when really, the big decision of my life took place. I had an offer from Bell Laboratory in what was called the mathematics group, where intellectually it was the top group in the Bell Telephone Laboratory. And an offer from the department at MIT. And by then I had kind of come to realize that teaching and research went very well together. So I stayed here.

INTERVIEWER: Can you talk to me about how you wound up making that transition, after the Radiation Laboratory to Lincoln Laboratory?

FANO: Why I was involved in Lincoln Laboratory? Well, to start with there was a very great concern about defense, air defense. And I was in a committee that met in the evening in the conference room with my department trying to find something. And that committee-- I was no longer involved-- but made a study that was presented to the government, and that was the beginning of Lincoln Laboratory.

I was a member of RLE at that time. You know what I mean? Yeah. And as a matter of fact, what happened is Building 22 of the Radiation Laboratory was renovated to house the beginning of Lincoln Laboratory. And I was head of one group. I mean I was interested in radar. And actually, I did a piece of work that was unknown for quite a while. I made a total analysis of the behavior of radar if the direction was synchronous. And there was a report of Lincoln Laboratory, which was classified secret so I couldn't publish it.

And I was head of that group. But then Lincoln Laboratory moved out and it was impossible to teach at the same time as working there. So I quit. But their group continued and a colleague of mine, Bill Siebert, became the head of that group. And then they developed a radar system based on my work, which went to Turkey. And they could keep track of missiles coming out of Russia without them being able to tell that they were being watched.

INTERVIEWER: So you separated from Lincoln when they moved to Bedford?

FANO: Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: When you were still with Lincoln Lab, and it was here, and it was still based at MIT, was there a difference between the climate in the laboratory and the climate of MIT in general?

FANO: No. INTERVIEWER: No. They had the same sort of culture?

FANO: Well you see, essentially what it was at that point was kind of a militarily classified part of the Research Laboratory of Electronics. And that part became part of Lincoln Laboratory. So it was no big transition. And I had two offices, one in Building 22 and another in Building 10.

INTERVIEWER: So I guess that sort of brings us to Project MAC.

FANO: Oh, there is a lot before that.

INTERVIEWER: Fill me in.

FANO: A lot before that. The whole information theory.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, right.

FANO: You see once you get your doctorate, you have to start thinking of what you're going to do after that. Because I wanted to get out from the-- what you call the shadow of my mentor-- and be on my own. So I was looking for ideas. And at that time, the big story was cybernetics. And-- oh, what's his name now? Block.

INTERVIEWER: May come to you later.

FANO: Norbert Wiener. And Norbert Wiener had a habit of walking around MIT and butting into people's laboratory, offices, and say something. So at one point he came to my office and said, you know-- with a big cigar, you know. You know, information is entropy. Then he walked out. That's what just happened.

So why did he say that? He didn't explain it. So I started to think of what it could possibly mean. And again, I wasn't getting anywhere. And then, at Christmas I was walking from my apartment to Back Bay Station and the light came. And so it turns out that Claude Shannon at Bell Telephone Laboratory had done a tremendous amount of work in the area. I knew from Jerry Wiesner that he was involved because Jerry Wiesner, Claude Shannon, and Louis Smullin knew each other at University of Michigan as undergraduates.

No, it was not at Christmas. That was when I was going to the meeting of the Institute of Radio Engineers. And on the train I worked out all the detail, and then I went to see Claude Shannon. He was giving a paper at that meeting. He was really not interested, but he allowed me to go and visit him at Bell Laboratory. So I went the next day, I told him what I was doing, and in the train and then his face lit up. I described a different way of doing what he had done.

So that got me started. And then Claude Shannon came out with his work, and actually I wrote an RLE paper on the work that I had done. And I wrote it because Claude Shannon wanted to quote me. So I had to give him something. I had to get the report. But I wrote something more, and then I got interested in the whole thing. And in 1950 I started a course on that. And I taught that graduate course until '61. And I got switched.

INTERVIEWER: So how did you wind up getting from information theory to Project MAC?

FANO: Well, it's a complicated story. First of all, 1961 was a critical year for me because almost everything that I was doing came to an end. Let me say something else. Because during the second half of the '50s, I was heavily involved in the development of the new set of courses for the Department of Electrical Engineering. Professor Brown was the head of the department and appointed me to develop one particular course. So one term, I was teaching that undergraduate course. The other term I was teaching information theory. And I was writing a book in both. And by 1961, almost at the same time, the two books came out. So I'd finished.

So I was thinking about what else to do. And it was pretty clear to me that computer were an important field that was coming that would change the way you implemented a lot of things. And so I was thinking of going in the computer field. But at that point I took a sabbatical at Lincoln Laboratory. Actually, I didn't do much of that. I did something else when I was there. I did some more work on information theory. But when I came back, I was involved with computing a different way.

MIT had a problem to solve. Namely, the computation facilities that were available courtesy of IBM were insufficient. Something had to be done. So a committee had been appointed to try to do something about it. And I was a member. There were three of us, including Professor Morris, who was the head of the Computation Center. And so I was getting involved with computing in a sense.

But then something happened and this is a long, complicated story. You know the name Licklider?

INTERVIEWER: From my research, yes.

FANO: Yes, OK. Lick, as he was well known, had come up with a vision, really, and wrote a paper on online use of computers in science. At the same time ARPA was looking for somebody to head a piece of ARPA which involved, among other things, computers. And they interviewed him and he kind of really impressed people at ARPA. They wanted very much to get him. And among other things at that time, Eugene Fubini was assistant Secretary of Defense-- an old friend of mine from Italy. His son wrote a book about him recently. And Licklider went to Washington. So he started beating the drums about computers, and among other places, came to MIT.

Now Professor Corbató, who is now my office mate and friend, had developed a timesharing system capable of providing simultaneously opportunity for various people to work online on a computer. And by then I was familiar with their work. Now, it was very clear that Licklider wants very much to start a big project at MIT. And there was no computer person old enough to be given the responsibilities to do it. And I felt very strongly that it should be done. So I said if nobody wants to do it, I'll do it. So that's how I got involved.

So this in the fall of '62. There was a big meeting in Virginia. I went to the [INAUDIBLE] computer that I attended, and Licklider was there. I attended for what reason, I was chairing a session on communication. And on the way back we talked a lot and he sold me on it. And it went very fast. That was the day before Thanksgiving. And on Thanksgiving day I kept pacing the house and eventually I decided, I'm going to do it. And the next day I had an appointment with the provost to do with something else, and I told him that I was thinking of doing that. And I said, what do you think? And he said, go ahead.

So that was a Friday, because the Friday after Thanksgiving was a working day at that time. And the next Thursday Licklider was coming to town. So we all met in the president's office, who was Stratton at that time. And we shook hands, and that was it.

INTERVIEWER: And that's the beginning of Project MAC?

FANO: Well, it's not that easy. It was a gentleman's agreement. We're going to do it. Then of course, I had to write a proposal, which I did. And in general, that proposal went to Washington. And all sorts of things had to be done. And Licklider wanted to start the whole thing with a summer study, which had to be organized. So that was on July 1-- oh, yes. Stratton asked me, where are you going to do it? And by then I already found out that in the building called Technology Square-- there was only one building going up-- the top floor had been leased by a computer company in Washington, who I was told-- the two top floors-- wanted to get rid of it. So I said, probably I can get it. So in fact, I got it. And the top floor was supposed to be for a very big computer, and we were going to have a very big computer, so it was fine. And the floor below was for offices. So everything worked right.

There was no room on campus. And Professor Morris, who was the head of the Computation Center, had a-- his statement was, MIT was caught with its buildings down. Which was the case. Just there was no space. So how we ended in Technology Square. And that was big ado,

We had our own computer system, operating system, that Corbató-- Corby for short-- had developed in the Computation Center and that became famous. And I had I don't know how many visitors and reporters, and all sorts of things. As a matter of fact I was informed, it was about two weeks ago, that there was a movie of me on YouTube. I don't remember doing it. It was probably done in late 1964 after the news outlets had learned about Project MAC. But you see at that time it was something completely unthought of.

INTERVIEWER: No one at that time sort of understood where computers were going.

FANO: Yeah. The idea of people using a computer online was completely new and what you could do with it. For instance, the contracting officer in the government for Project MAC was not ARPA. ARPA pushed the money around. It was the Office of Naval Research. And he had contracted men, came to visit Project MAC. And we sat in front of a computer on a typewriter. And he was so stunned by it that he gave some additional money to develop a system for him to use. This was the situation. I went all over with United States and abroad demonstrating that capability.

And then there was the real big system that was designed called Multics. It was designed in collaboration with Bell Telephone Laboratory and General Electric. It took a lot longer than expected.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. I have a note that there was an expression called "build things the Multics way." Can you explain that?

FANO: I don't know. That's not an expression that I know.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, OK. So what is the story about Multics?

FANO: Well, I mean it was a big enterprise to do it. A huge system and very difficult to design and to implement. And it worked well.

INTERVIEWER: What was its purpose?

FANO: It was a timesharing system. Much more powerful than the original one. The original one was an IBM 7094, which was not a very powerful computer. It was old. Well, the whole question of what computer to use was a big one that we had to decide. And we had a big fight with IBM. They expected to use their computers, but their new system, 360, was totally inappropriate for what we were trying to do. So it turned out that General Electric had something that we could use effectively. So we went there, and that was a big fight.

INTERVIEWER: Tell me more about the fight between--

FANO: Well, I mean I informed high up at IBM right away what we were doing and what our intentions. They didn't take us seriously. When they were not really helping much and I went to see the person that was very high there, it was a vice president. Then well, he didn't take me seriously. When I mentioned, I said, you know, IBM is not the only company to make a computer, he thought that what I had in mind was Digital. And IBM was not worried about Digital. Instead it turns out to be General Electric. And IBM was very worried about-- it was the only company that could compete with them.

So they hit the ceiling. They ran to Jay Stratton.

INTERVIEWER: But you didn't wind up getting what you needed from them?

FANO: I mean, they couldn't provide what I wanted. They couldn't provide it. Just the whole design was wrong. And they tried, afterwards, to have a [particle?] assisted by modifying the 360 that could be used for Lincoln Laboratory. It's a complicated story. It did work, but it was as slow as molasses.

INTERVIEWER: Now, Project MAC was created as a project instead of a laboratory. Why was that?

FANO: Why was that? At MIT faculty was in department and most of them in a laboratory. And you couldn't be in two laboratories, that was not the right thing. So in order to get lots of people involved, I had to use a word other than laboratory. Project, that's what it's called. And that made it possible, the participation for a heck of a lot of people. Actually, what I did, I supported the laboratory in which they were working, so they could work with us.

However, at a certain point-- from the very beginning-- let me go back a bit. What I wanted to do was not just what ARPA wanted me to do. I felt that computer science was going to be a very important thing. And I wanted to take that opportunity to start building computer science at MIT. That was my goal. Including the educational part, not just the research part. But at a certain point I think it was the time to switch to the term laboratory. But the higher up won't let me. Because I could not persuade them that computer science was here to stay. Only later on, Dertouzos years later was able to persuade them. That's not to do with my department head. It's higher up, dean and--

INTERVIEWER: Was it the two years later where Project MAC sort of became CSAIL?

FANO: No. This is much later. Oh, no. Project MAC, as a matter of fact, I resigned as director in '68. I'm not interested in management. I did it because it had to be done. Because if I didn't do it, nobody would. So I passed, and I thought that that was all right, but that instead created a lot of problems. And I don't know what happened, but he got into a fight with-- oh, what was-- yeah, name?

INTERVIEWER: Names are hard.

FANO: Head of Artificial Intelligence. A friend of mine. And that's what happened. We'll get it.

And they got into an argument. I don't know about what. Because Artificial Intelligence was part of Project MAC. And the whole thing went to-- they wanted to split. And they went up to the provost to approve this split, and Licklider resigned. It was a very unpleasant thing. So Artificial Intelligence becomes a separate laboratory. It was a group in Project MAC. And then, finally, in 1940-- what am I saying? In 2003, the decision was made to put together again the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and the Laboratory for Computer Science was the new name for Project MAC. So they merged into CSAIL.

INTERVIEWER: So they started together, separated, and then came back together.

FANO: And it really was kind of a nice thing because this was July 1 '03, which was the 40th anniversary of the founding of Project MAC. And there was also the birth of the new laboratory put in together. And there was a big cake with its name. And the director of Project MAC, the former director, me, and the new director of CSAIL, we cut the cake together.

INTERVIEWER: So during these years, this was a very good time for federal funding for research, wasn't it?

FANO: Well, at the time that Project MAC was formed it was a very good time. Licklider had plenty of money, basically our budget, which was quite large was $3 million a year, with two years ahead. So it was a very, very good funding. But then, remember, this was during Vietnam. Things got tight and ARPA started being less favorable. I mean, this was after I was no longer director. But while the contract with Project MAC was really open in terms of research-- in other words, I was presenting a proposal, but it was a general thing with not much detail. And later they wanted to work on specific things that they wanted, so it became tougher. And I don't know what it is today. It's not very easy now.

INTERVIEWER: So when you initially were getting federal funds your research, am I correct that you had a lot of control over what you did, but as the years went by--?

FANO: They started being picky about working only on certain things. Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Right.

FANO: You see when I founded Project MAC I had very much in mind the organization and funding of the Research Laboratory of Electronics in which I grew up, basically. Coming out of the Radiation Lab, the Research Laboratory of Electronics was founded as a successor to the wartime laboratory. And the funding was a general funding. The three services were funding the laboratory. Now, later on, they also had other sources of funding. But the beginning was that. And the director of the laboratory had full control over how to use the funds. Of course he made a proposal, but he had full control. Now I never had to make a research proposal until I started Project MAC. And I never had to do that since.

INTERVIEWER: In terms of Project MAC, I wonder if we could talk a little bit about, I guess, what the three main areas of research that were going on. Maybe you could just explain a little bit about the thinking. The first one being operating systems.

FANO: Well, the big project was a timesharing system. But there were faculty interested in other derivatives of that. Not only, but just the development of the system involved a lot of problems, a lot of doctoral theses were done in that. But there were other things which developed more later on. But one important thing is that in starting Project MAC, I didn't go around hiring people-- well, faculty-- except for the programmer under Corbató, who's a member of the faculty you see. So it was really a faculty-run operation completely.

INTERVIEWER: Is it true that a lot of the early computer research was done by undergraduates, which I think was pretty unusual back there, rather than graduate students?

FANO: What do you mean?

INTERVIEWER: A lot of the help and support that you got at Project MAC you got from undergraduate students at MIT?

FANO: Not much.

INTERVIEWER: No?

FANO: There were some, but mostly were graduate students.

There was an older center-- well, you see there was a group at MIT, a society. It was called the Railroad Model Society. What are those called? You know what I mean. Model Railroad Society. And there was a lot of undergraduates having fun with that. That group got interested in the TX-0 computer that was given by Lincoln Laboratory to my department, you see, to fiddle with it. That, yes. And some of them became graduate students, but I would not say that most of the work was done by undergraduates. Quite a few of them then were involved in artificial intelligence, but artificial intelligence was another separate thing.

INTERVIEWER: While people were working on the timesharing, they were also developing the sort of groundbreaking stuff for operating systems and artificial intelligence and computation--

FANO: Well, that's right. They were doing a lot of work on computer systems-- programs and languages and new ideas. You know, I always intended, and I stated in the beginning, that Project MAC was going to be a general laboratory in computer science. That was my idea from the beginning, there was no question about it.

INTERVIEWER: Just had to convince other people.

FANO: That's right. I had problems.

INTERVIEWER: So can you walk me through how the Department of Computer Science was created?

FANO: There is no Department of Computer Science. There is a Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

INTERVIEWER: OK. The story of how you were able to convince people at MIT that computer science deserved its own area of study?

FANO: Well, within the department I had to deal with two department heads, friends of mine. And I had full support. Peter Elias and Louis Smullin. Peter Elias was department head when started Project MAC. I had, of course, the support of Morris, who was head of the Computation Center. I mean, really he should of done Project MAC, but he had a finger in so many things that he couldn't possibly do it. He told me so. And he helped me in any way he could. I created an advisory committee, which was serious, of key people at MIT-- starting with the provost, and department heads, and the head of the Sloan School-- to help me. Because it was really an MIT project. So I needed help, and they gave me a lot of help.

INTERVIEWER: Go ahead, tell me about that.

FANO: Well, I mean, I said a few things. It started when I was a teaching assistant and instructor. All my time went into the teaching. And I had to learn things-- I was, call it, two weeks ahead of the students and they knew it. For instance when I said I was teaching the course, the first course was Electronics for Communication. Well, I handed my first roll, my class, a bunch of radio hams. I'd never been a radio ham. And they came out, last night I was doing this or that and this happened. Why? I had to contend with that. I managed. I taught all sorts of things at that time. I always was involved with both undergraduate and the graduate courses until late.

INTERVIEWER: So early on you thought teaching was not going to be particularly interesting?

FANO: No, no. I never think that.

INTERVIEWER: Well, you didn't think you wanted to be a teacher?

FANO: I didn't want to be a professor. Not because I had anything against teaching, but there's a kind of life-- you know, I was young and I wanted to do things.

INTERVIEWER: So from that position to where you feel now that teaching is sort of the most important thing, how did that change--

FANO: Oh, immediately.

INTERVIEWER: Tell me why.

FANO: When I was a teaching assistant I enjoyed doing it.

INTERVIEWER: What is it you like about the teaching?

FANO: From a personal standpoint, was the effort to clarify things so they could be presented clearly. It's a challenging piece of work, you know. Well, let me tell you something first. I did a lot of writing-- books and other things. And there are times-- for instance when I wrote a book, I may spend the whole day on the first page of a chapter. And the reason is because unless you start talking about something from the right point, you can't write well. Your writing becomes all interlocked with, "but," "that." There's not a clear line. That's very interesting.

As a matter of fact there is a cartoon that my older daughter gave me because I was telling things when she was at school, which is about somebody trying to write something. And there is a lot of [INAUDIBLE] And then the final thing is the statement. Writing is nature's way of telling you how sloppy your thinking is. So basically what I'm trying to say, what is interesting about writing is that it forces you to think through things. And thinking through all the results. This textbook that I wrote-- well actually, there are two textbooks on electromagnetic theory. The one that I wrote--

INTERVIEWER: Is that the theory of microwave filters?

FANO: No. No. The book.

INTERVIEWER: Electromagnetic Fields?

FANO: Energy and Forces. That one I wrote. And it's quoted officially with Chu and Adler. But my name also is in the book that Adler wrote-- you probably have listed too. He's just the author. Chu is still in the middle, because Chu gave me some very important ideas. That book was in use for a long time.

INTERVIEWER: And translated into a lot of languages.

FANO: Not that one. No. But it was published in Taiwan. You know what I mean? A lot of copies that went out. The publisher here, Wiley, was pretty amazed of that. Now the information theory was translated in Japan, in Russia, and in Germany.

INTERVIEWER: Why do you think that one had such international interest?

FANO: It was the first. The first textbook. You know, it took a while. I wrote class notes every year pretty much, but only in 1960 I just put it all together. One term I just wrote all the chapters, and the MIT Press published it with Wiley. And it was a nice experiment, because I was in a hurry to get it out because we needed a textbook. So it was not set in print. It was-- I don't know what you call it-- mimeographed? I don't know. But there's a book. It's a very interesting thing happened that it was typed by my secretary on big sheets and then shrunk in size to the book. Very dense. And it turned out that I had trouble reading the big and no trouble reading the small, contrary to what I would expect. Now the other thing is that the publisher, MIT Press, didn't receive my last two chapters until everything else had already been published-- I mean ready. So the book came out immediately after I handed in those two chapters.

INTERVIEWER: Then how did they get this last two in?

FANO: The same process they had for the others. It was just very quick. It was not setting in type.

INTERVIEWER: When you think about the research you've done and the books that you've written, what would you say are your most important or interesting--

FANO: Well, I was asked that in 2002, on the occasion of the centennial of the department. I was asked, all the faculty were asked to say what was the-- in our judgment, our most important piece of work. You know what it came out to be?

INTERVIEWER: What?

FANO: My doctorate thesis. It was.

INTERVIEWER: And why?

FANO: Well, I mean to tell you-- once I was at Stanford and I had time in my hand. I wandered into the bookstore, and there I found a book, a whole book based on my thesis. It was widely used. Surprisingly, and I never understood why, my mentor, Professor Guillemin, was never excited about it. I don't know why.

INTERVIEWER: So you make that judgment based on the fact that that work was used by a lot of other people?

FANO: No. Intellectually, it was quite a piece of work.

INTERVIEWER: Was that the one that was the most engaging for you?

FANO: Those are things it's hard to say why. That was a concentrated piece of work while the other was kind of spread. I mean I have patents, but that's a different story.

INTERVIEWER: So I want to ask some-- I have a bunch of--

FANO: You want the title of it?

INTERVIEWER: The title of the dissertation?

FANO: Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Go ahead.

FANO: You have it?

INTERVIEWER: I think I do, but not in front of me right this second.

FANO: Theoretical Limitation on the Broadband Matching of Arbitrary Impedances. Is this long enough for you?

INTERVIEWER: Yes.

FANO: OK.

INTERVIEWER: Yes. Let me ask some questions about MIT specifically. What's kept you here for your career?

FANO: I was happy here.

INTERVIEWER: Well, what was it about this particular environment that made you happy?

FANO: Oh, it's hard to say. I always worked with nice people. You know, it was a nice environment. It was a chance of doing pretty much what I wanted. And what I wanted and did was appreciated, so why not? Lots of very nice people.

INTERVIEWER: Was the collaboration here of particular importance to you?

FANO: I wouldn't say that it was. You know, of course we collaborated, but I don't know. It's a nice place to be. I know lots of people that I got along very well, and friends, and I had good relations all the way up to the presidents at all times. You know, MIT was a homely thing. You felt at home. And all through my life the faculty had the full trust in the administration. Well, things are changed.

INTERVIEWER: How have things changed?

FANO: Well, I mean first of all, MIT grew tremendously. I arrived here and MIT was the whole building. And everything else around was parking space. So there was a lot of construction, a lot of new things. When I look at my department, what it covered years ago and what it covers now, is just unbelievable. But there was always the spirit that things were going to be handled right.

INTERVIEWER: Have you noticed changes in the students over the time that you've been here?

FANO: Well, first of all, you must remember that I retired 25 years ago. I don't know what the-- I gave you my birthday. November I'll be 92. So you know, there's a lot of period in which I hang around, I don't do anything. I just come in on Monday because there is a faculty lunch and sometimes on Friday because there is a seminar created by my colleague and friend, Moses. Actually, I gave him his job first. I hired him way, way back. It's changed a lot. Much, much bigger now.

INTERVIEWER: Are there any other ways in which you saw changes?

FANO: Well, I mean there are all sorts of changes that goes with it. I am an old guy now. I don't know whether I'd like to have much change, but you know, that's what it is. I live at MIT in the era of electrical engineering. And in some extent, I created the computer science here. You know, I hired people, but basically I was associate department head. Did I tell you that?

INTERVIEWER: No, we haven't talked about that.

FANO: OK. All right. Then let me add this. As I mentioned before, my interest was to build up computer science at MIT through Project MAC. And I did. At a certain point in 1971, there was a fairly sizeable number of computer science faculty. And the educational program was on its way, too. And there was a visit of the visiting committee of MIT of the department. And the practice of the visiting committee is that have a session with faculty, particularly young faculty with nobody else there. And apparently faculty in computer sciences were not happy because they felt that there was nobody caring for them. And then Professor Smullin was head of the department, and he called me in and says, would you want to be associate professor-- associate head of the Department for Computer Science? And I said, sure. But what you have to do is also appoint a corresponding associate department head for the rest of electrical engineering, which I did. So I was from 1971 to 1974 associate department head for computer science. So I mean at that time, I wasn't doing much teaching as a result. Well, that's the other thing. I was not particularly interested in being-- of managing anything. But somebody had to do it. And I was obviously the right person. By that time I was no longer director of Project MAC, but I knew what was going there and I knew the whole faculty because most of the faculty I had requested their appointment.

INTERVIEWER: At other schools, at other universities, electrical engineering is not always paired with computer science.

FANO: All right, let me talk about that. It's always been my feeling that computer science fits with electrical engineering. And so did the department heads that I dealt with-- Peter Elias and Louis Smullin, so I had no problem there. At one point we had a guest from Berkeley, who had caused trouble in my view at Berkeley as it turned out, had split, insisted that computer science go in the School of Science, not engineering, at that time. And that was a bad mistake. But before it showed up as a bad mistake he was visiting here and he was basically trying to create a revolution.

INTERVIEWER: For the same thing to happen here?

FANO: Yeah. And well, he didn't go far. That would never happen over the dead body of Louis Smullin and mine. Never got close.

INTERVIEWER: What do you think is the--

FANO: Now the reason is not only that they belong together, if they are split, computer science will not be in a place where it's appreciated. That's what happened at Berkeley. At Berkeley they went back because the School of Science didn't care for computer science.

INTERVIEWER: I guess I'm not clear. What's the advantage of keeping the two disciplines together?

FANO: Let me put it bluntly. If you have separate computer science, electrical engineering, we'll have to build up competence in computer science separately. You need it. As a matter of fact, now there are two associate department heads, but they don't call themselves for computer science and electrical engineering. They're just associate department.

Actually, I have my own pet way of talking about computer science. It's the science of complexity. I can't sell it, but that's what it is.

INTERVIEWER: Explain that to me.

FANO: Let me give you an example. A lot of work is going on in computer biology. Biological systems are very, very complex and you need tools to deal with them. That's computers. But you know, it's not just a computer, it's the whole idea behind it. They are the tools, the science of complexity. That's what it is. It's in that sense that the rest of electrical engineering needs it because there are complex things to do. So if it were separate you have to create your own competency in the house anyway, so might as well start it that way. But I say, I repeat it. There was a time that selling the administration-- you know, higher ups-- that computer science was here to stay was not easy.

INTERVIEWER: When you think about not just electrical engineering and computer science at MIT, but when you think about MIT generally, what do you think makes it unique or special?

FANO: I say, first of all, we need specialized schools like MIT. I think it was Jim Killian that coined the phrase, it is a university polarizing science. That's what it is. So it is this, like Caltech. It's the same thing. And we need schools of that type that really the whole effort is in that because they're a very, very important area. Now, MIT for whatever right or reason has been top flight for a long time. I knew about MIT when I was in Italy. And I thought it was too good for it to admit me. Remember, I told you. There was no question when I got my doctorate that MIT was the superior school and electrical engineering department. It has always been, I hope it will keep by.

INTERVIEWER: Do you think by being at MIT that that has opened doors for you that maybe wouldn't have been opened if you had been somewhere else?

FANO: I don't know that. That's hard to say. Of course, it helped my career because it is MIT. There are opportunities at MIT. I mean, how many schools of engineering were revised totally during the graduate curriculum? MIT did it. It was a total revision. Total emphasis. A set of seven different courses were developed. Mine was one of them. You know, it can do things. I don't say that the others cannot, but certainly, traditionally MIT has been able to do, to be at the front.

INTERVIEWER: When you think about where electrical engineering and computer science might be going in the future, what do you see?

FANO: Oh, there are all sorts of things. What is getting very big is robotics. The big thing there. And then while my life was in the center of electrical engineering, when it blossomed and became very important. We are getting into the center of biology. There's no question about it. But the department is involved there too. We have faculty in there. So electrical engineering is a great intellectual center, which blossoms in different directions at different times. So now both the theoretical aspect and experimental effort keeps growing into new things.

INTERVIEWER: You mentioned that electrical engineering, what used to be taught and then what's taught now is very different.

FANO: Oh, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Do you see that changing more as you go forward?

FANO: Yes. The real problem is that all of engineering is too much now. I had an idea that I'd been trying to sell, but unable to do. Is that engineer has to become a professional school, not an undergraduate school. And what you need is just too much. What you need is a foundation in science at the undergraduate level-- broad foundation in science and then a professional school of engineering. I tried to sell that for my former president, Chuck Vest, when he became head of the National Academy of Engineering. But I couldn't. Because that's not something that can happen locally. It has to be a movement over the whole country. And only the academy can manage that. But no go.

INTERVIEWER: Not yet.

FANO: Not yet. Has to be, there's too much. And just adding a fifth course in Master's degree is not enough. A doctorate is a different thing. A doctorate is specialized research. We need that too. But what you need is too much breadth that really should be presented to students in too little a time. So something has to happen. My oldest granddaughter is in the last year of medical school. Well, she has an undergraduate degree and then in the medical school. And that's not the end. And then there are other things. Now she's getting into being interviewed for-- what do they call it? Residency. It's a long period. Well, I mean the idea that you can be an engineer in four years doesn't make sense now.

INTERVIEWER: So it used to work, but it doesn't work.

FANO: Not only, but there are other things. 1982 we had the celebration of the 100th Anniversary of electrical engineer. You know, it started in physics and now there's a separate department. It became a separate department in 1902, I think it was. I was asked to chair that enterprise and I thought it would be nice to have a study to go with that. And it turned out we had a study of what we call, lifelong cooperative education. And we wrote a report-- actually, I wrote a report on it. Well, I did some research and talking. I went around the country talking with engineering executives that I had access to. And we wrote this report and basically, the situation is that the effective life of most electrical engineers is 10 years after graduation.

INTERVIEWER: And then their information is outdated?

FANO: That's right. But it's more than outdated because new things come in and many of them are based on scientific knowledge they didn't have. So it's not just a question of taking some specialized course. It's just keep modernizing the background. And we really tried to launch that, but partly it happened to be a period in which the industry wasn't doing too well. But basically my calculation was that to keep engineers updated, the employers had to allow something like 10 percent of their time to be devoted--

INTERVIEWER: That's why it didn't work.

FANO: Huh?

INTERVIEWER: That's why it didn't work.

FANO: I know. This is not only the engineer, the managers too. And that was not only listening to class, but teaching them. In other words, I had to be what I called a broad intellectual community that involved industry and university because we couldn't do it. We could provide the stimulus. As a matter of fact, after that, there was a course in computers. The first beginning course in computers, which was used in industry. And the first time it was taught to our own faculty. Paul Gray was very interested in this and he arranged for Louis Smullin and me to meet with top people. We met at the airport in Chicago. Well, they told me, why don't you start it locally. So I tried to do locally. And Ray Stata helped me, but it didn't fly.

INTERVIEWER: Do you think they'll come a time where that will actually happen? Where the concept--

FANO: Well, it's happening, but not completely. There are a lot of courses being taught, new material being taught by professional society and by schools, but this is more because it involves also the foundation. And the foundation that you need, the science foundation and mathematics foundation that you need keep changing.

INTERVIEWER: So what do you think will-- how will we fix that problem?

FANO: I don't know. I try. Try my best with some good help, but it didn't fly. Part of the problem is people as they get older-- let me start at the beginning. When I was an undergraduate anything that you put in front of me I would learn it. When you get a little older in the late 20s, you kind of want to have a reason for learning something new. You don't learn it just because it's there. And that's a problem. You're not used to new things, so it is very important to have the education be somewhat of a continuous operation. And the idea is that somebody finishes degree, goes to work in industry, and industry is organized to continue the learning. The people there will teach you because university faculty can't do that-- too many. Should there have been local teachers. And by teaching, also they learn. It's a good idea, but it hasn't been working.

INTERVIEWER: I've asked a lot of questions. I'd like to leave a few minutes for us to talk about anything that you think is important that we haven't talked about yet.

FANO: Oh, now I have to think of one.

INTERVIEWER: Particularly if you have any perspectives or impressions about MIT.

FANO: Well, let me say something, but without getting into it. There are trends at MIT today that I don't like, but I don't want to get into it.

INTERVIEWER: Do you want to name them?

FANO: No. Well, I can name what-- very broadly. One is that MIT in some respect acts like a university, general university, which it's not. And that is causing trouble I think. And there are many things in there.

INTERVIEWER: Are talking about the inclusion of more humanities in the education?

FANO: No, not the inclusion. It's other matters. But I don't want to get into it.

INTERVIEWER: OK.

FANO: The other is-- all right, let me start with this. The size of the MIT faculty has not changed for decades. The number of undergraduate per year has not changed for decades. However, there have been lots of things happening at MIT. Well, I'm sorry. The graduate student has grown tremendously. Now, already how can the faculty handle a lot more graduate students? But then MIT's getting involved in all sorts of things. How can a faculty [INAUDIBLE]? The net result, and there are a lot of research staff, administrative people to handle all these activities that MIT's getting involved for money.

INTERVIEWER: Are you concerned that the focus on teaching is being lost?

FANO: The focus is that the focus on teaching and research on the part of the faculty may be lost.

INTERVIEWER: Too many demands on their time for other things?

FANO: Yeah. I saw that there are all sorts of contracts, Cambridge and Singapore, and now they're talking France. And there are all sorts of industries that don't want to spend money in their own research laboratory and trying to get MIT to do research for them. That's a problem.

INTERVIEWER: Is there anything else we haven't talked about?

FANO: There are lots of things and nothing. Did you get a good perspective?

INTERVIEWER: I think so. But this is also your opportunity if there are comments you want to make.

FANO: No. You can talk of the time when I was active. Now I'm inactive and I don't want to go into that.

INTERVIEWER: OK.

FANO: I'm a peripheral observer. Well, I mean I devoted my life here and I'm happy about it. Now I actually taught for 43 years. Well, including the period that was Radiation Laboratory, which was short. I think I was properly recognized. I think my brother and I were one of the few brothers that were both members of the National Academy of Science, which is nice. I got into the National Academy of Engineering, but I think I got into the National Academy of Science because there were a lot of physicists that knew me from the Radiation Laboratory. So I had a good life I think, professionally speaking.

INTERVIEWER: I would agree.