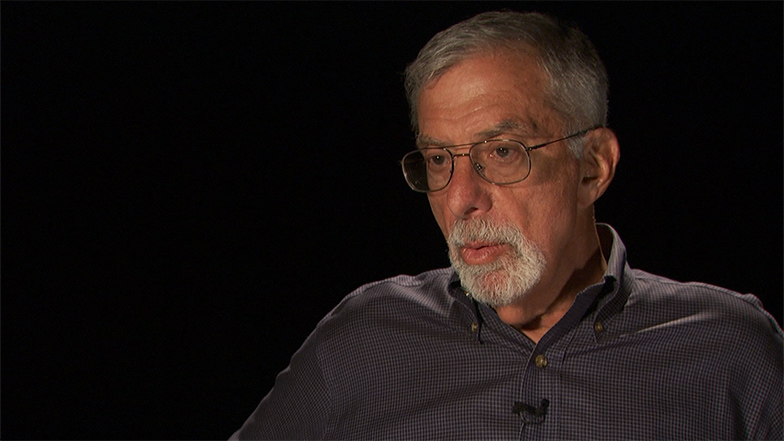

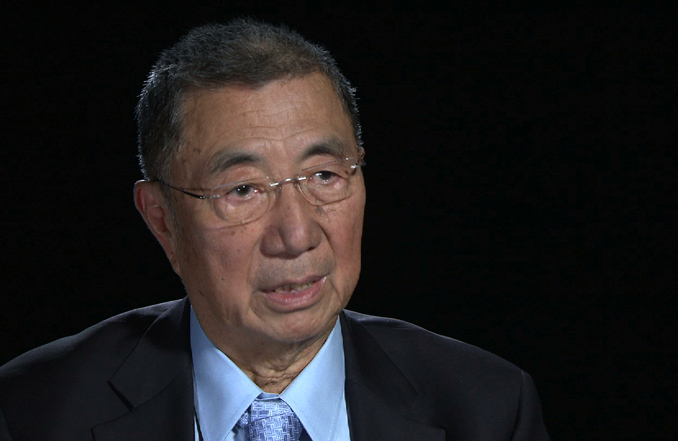

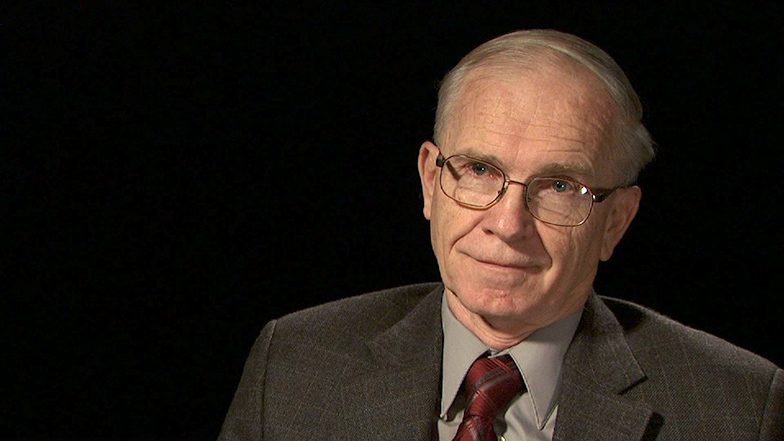

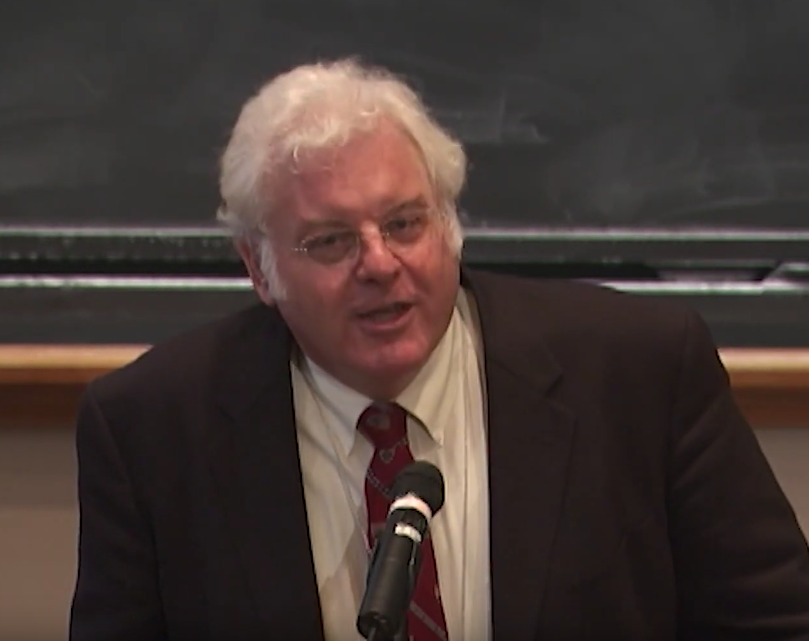

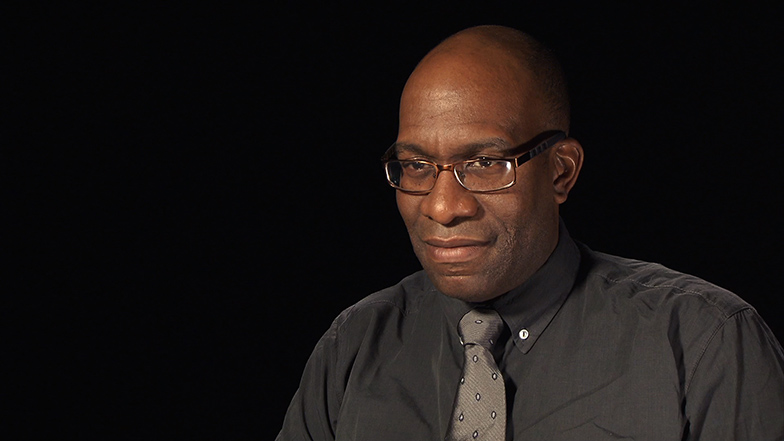

Richard R. Schrock

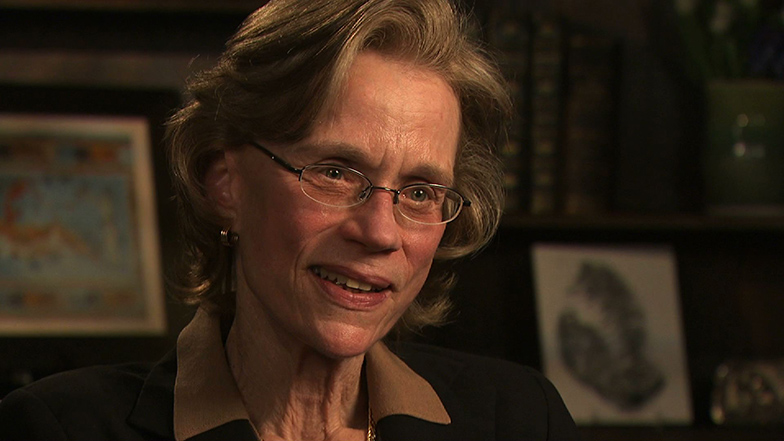

INTERVIEWER: Today is June 30, 2011. I'm Barbara Moran, and today we are speaking with Richard Schrock as part of the MIT 150 Infinite History project. Dr. Schrock was born in Indiana but spent his high school years in San Diego, and obtained his BA in 1967 from the University of California at Riverside. He attended graduate school at Harvard, receiving his PhD in organic chemistry. He spent one year as an NSF postdoctoral fellow at Cambridge University, and then three years at Dupont before coming to MIT in 1975.

At MIT, he became full professor in 1980, and in 1989, the Frederick G. Keyes professor of chemistry. In 2005, Dr. Schrock won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of the metathesis method in organic synthesis. This work has opened up new opportunities for synthesizing molecules that streamline the development and production of pharmaceuticals, plastics, and other materials. Welcome, Dr. Schrock.

SCHROCK: Thank you.

INTERVIEWER: Thanks for being here. So to begin, I have to ask you the first question I would ask any chemist, and tell me about your first chemistry set.

SCHROCK: Well, it actually was a chemistry set, first of all. And that was when I was eight years old. So it was a great little chemistry set. Had a lot of good stuff in it.

INTERVIEWER: And it was a birthday present from your brother?

SCHROCK: From my brother. Yeah. I have two brothers. The one five years older was then in high school. And he was very good in chemistry himself. So he thought I might like it.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. And you did?

SCHROCK: I did.

INTERVIEWER: And I understand you set up a little corner in the garage, the woodworking shop? How did you--

SCHROCK: It was, I don't know what you'd call it, a cannery where you kept canned goods in the back.

INTERVIEWER: Pantry.

SCHROCK: Yeah, a pantry. And I took it over.

INTERVIEWER: Now most kids get a chemistry set. And they play with it for a couple weeks. And then they never play with it again. But you seemed to really take to it and expand on it and keep the interest alive. What was it that you liked about it, even at that young age?

SCHROCK: I could make things, transform matter. I could do stuff.

INTERVIEWER: Did you ever do anything dangerous?

SCHROCK: Yes.

[LAUGHTER]

You want me to tell you about that? Oh, let's see. I can't really tell you in detail. But let's say, it's easy to make things like gunpowder, right?

You have an oxidizing agent. You have something you can reduce. And then you have fire. And those two make gunpowder. So it's sodium nitrate and charcoal and sulfur, basically.

INTERVIEWER: I understand there was at least one incident where the fire department was called to the house?

SCHROCK: That's true. There's one incident.

INTERVIEWER: So did your parents encourage this? Were they happy about your--

SCHROCK: My parents always supported what I did. I think they didn't like the fire department coming to the house. But yeah, both my mother and father were very supportive.

INTERVIEWER: Can you tell me a little bit about your upbringing? I understand you grew up in Indiana. You seem to have this very idyllic boyhood, with lots of woods and mud puddles and that sort of thing.

SCHROCK: That's right.

INTERVIEWER: Please tell me a little bit about that?

SCHROCK: So I was born in Berne, which is a little bitty city in Indiana. And my parents were actually of, well, they call themselves Plain People. But they were really Amish, an Amish sect. And so there was a break in the church. And my parents left that little town and moved to Decatur when I was nine months old. And in Decatur, of course, they became more modern. So my parents did not go back, as did my father's brother and his mother, to the old ways, you might say.

INTERVIEWER: Your parents came more modern.

SCHROCK: Yes. His brother and mother then became, I don't want to call it more primitive, but back to the old ways, no electricity, no running water. They even moved out of that area. Anyway, Decatur was much more an environment where my father felt more comfortable, and my mother.

INTERVIEWER: And they came of age in the Depression and had two sons during the Depression.

SCHROCK: They did, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: How did that affect them?

SCHROCK: Well, I can't really speak to that. Because I read things, but, of course, I wasn't around at the time. But it was very, very difficult for everybody. And they were, however, generally on a farm. They were just being brought up, so my mother's Depression age is 20-something. And they were married at about that age.

And then they worked on a farm. So they had enough to eat. They didn't have any money, but they were okay.

But it was still difficult, and very demanding physically, and working day and night, and so on. But my father became a carpenter in Decatur, or was a carpenter, and furthered his business interests in Decatur. And that's what he was known as, or a cabinet maker actually.

INTERVIEWER: And he taught you and your brothers woodworking.

SCHROCK: He taught me, sort of. I went into his shop and taught myself, avoiding the power tools and so on. But yeah, tools were available, and wood was available, and techniques were available. And I from my earliest memories, five or so on, or something like that, yeah, was interested in woodworking.

INTERVIEWER: It's interesting. You have a brother who's an engineer, and one who's a surgeon, correct?

SCHROCK: Right. Both retired now, but yeah.

INTERVIEWER: And you ended up in chemistry. Were there certain things about your upbringing, or values that you got from your parents, you think that shaped you or sort of encouraged you and your brothers to go into these scientific or technical careers?

SCHROCK: Well, they didn't finish high school. They were not allowed to finish high school. So when they turned 16, they were taken out of high school, and went to work on the farm. By their elders, pulled out of high school. So we didn't see much of a future. I'm guessing now, my oldest brother, 10 years older than I am, or the one five years older, didn't see much of a future in that way of life.

So they valued education, I should point out. My parents valued education, and they always resented greatly the fact that they were taken out of high school. So they both got high school degrees when I got my high school degree, in 1963. And then my mother went on to get an accounting degree, and worked as an accountant for a couple of decades after that. And my father never went on, but remained interested in learning.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. That's amazing. They really sound like extraordinary people.

SCHROCK: Yeah, they were. They were. And so, I guess the question was, what did we get from that. Well, the values of education, they always told us that we should get an education. And we valued an education. We didn't see anything else in the future for us, and so that's what we did. And they, of course, taught us to work hard, and don't be discouraged, and a lot of the things that are needed to continue, for them, during the Depression of course, and then after that, for us. Although it was a lot easier for us.

INTERVIEWER: Sure. And it also sounds like at your childhood, you had a free run of the area, what seemed like a giant yard to you. Do you think that gave you an interest in the natural world, and in figuring out nature's secrets at all?

SCHROCK: Yeah, that's right. So we lived at the edge of town. My father bought an old house for maybe, I don't know, $10,000. And he fixed it up. And it was quite a nice house. It's gone now. There's a big Walmart or something there.

But it was at the edge of town, so there wasn't much else. There was the woods. And I could go out and hang out and look at what makes the world work. And so that's what I did. And I spent a lot of time just in an unorganized way, going around, looking at things.

There was what we call a tile mill. So they took clay out of the ground, and put it in cars, and hauled it over and made tiles. They went under the road near our house. And so there was a big, not a ditch, but an underpass, unfinished. And I would go over there. And I'd find fossils. And I'd wonder what these fossils are.

And of course, in Indiana, that was a great sea at one time, so a lot of fossils. Nothing very significant, at least, I didn't find anything very significant. But it exposed me to the world of nature and how things work, and certainly kept me interested. And then I had the chemistry set to fall back, right, when I went home.

INTERVIEWER: It's funny. That's one of those things that would have a fence around it now, right? You know, the ditch--

SCHROCK: The ditch, yeah, the ditch is gone. They filled it in. It's gone.

INTERVIEWER: So at what point did you start getting serious about chemistry, or more serious?

SCHROCK: Yeah, that's a good question. I would say, well, probably as I approached high school. I started to think, I like doing this. And I guess I never made a conscious decision. But I felt that I would like to continue to do chemistry. I don't think I ever thought much about anything else. I tried other things, of course. I had my instrument and so on.

INTERVIEWER: You mean a musical instrument?

SCHROCK: A musical instrument, but that didn't stick. Chemistry stuck, so, for whatever reason, all those experiments that we do, chemistry stuck. And so I figured out in high school that's probably what I want to do.

INTERVIEWER: Interesting. And then you-- because it seems like early on, you said, well, I'm obviously going to go to college and study chemistry. Did you ever, musical instruments aside, were there any other thoughts of medicine or physics or engineering? Or what was it? Was there something about chemistry in particular? Was it the, I don't know, the basic-ness of it, or the building things of it?

SCHROCK: Yeah, I think that's right. It's really the beginning of all things, in terms of transforming matter and understanding how to transform matter and so on. So medicine's a perfectly respectable field. My brother went on to become a surgeon, as you know. And he was very good in chemistry. He won the state championship, I think, in some chemistry contest when he was in high school.

And my older brother was an engineer. So those are certainly respectable ways to spend your time. But I felt that I really wanted to get to the basics, to really move those molecules and atoms around and reconnect them on a molecular level.

INTERVIEWER: Very interesting. So how did you end up at UC Riverside?

SCHROCK: So--

INTERVIEWER: Oh, sorry, let me back up and ask you one thing. Was there anybody in high school? Did you have any particular teachers or mentors or anybody who encouraged you to stick with chemistry, or to go on and study chemistry?

SCHROCK: There was one person. So he was my brother's teacher, when my brother was in high school. His name is Harry Dailey. He passed away a few years ago.

But he was very helpful. He would give me books. And I would use those books to do experiments. It's amazing what you find in old chemistry books. They tell you how to do everything. It's really amazing. I didn't do everything, but I did a lot.

And then he gave me equipment. And I also started to purchase equipment. And I loved the flasks, and the stoppers, and distillations, and all that. I just liked the physical-ness of it.

INTERVIEWER: Yes. Where does a teenager buy flasks and things like that?

SCHROCK: At a flask house. No, there was a scientific supply house, I think it was called, down in San Diego, near Balboa Park. And they had a lot of nice stuff in there, beautiful stuff, really nice. I don't know where you would-- no such place exists now.

INTERVIEWER: There's the internet, I suppose.

SCHROCK: Internet now, and of course, they're all gigantic companies, and so on. But this was just a little place. It had really nice, nice things. So I saved up my money from my paper route, and went and bought flasks and beakers and--

INTERVIEWER: And did experiments from the old chemistry book.

SCHROCK: Did experiments from the old chemistry books, probably things I shouldn't have done, but--

INTERVIEWER: But it must have all helped in there somewhere. So then you decided to go to UC Riverside. Can you tell me about that process?

SCHROCK: Yeah, so at first, when we moved to California, when I was 14, I was just going into high school. So I spent a half a year in junior high, and then three years in high school at Pacific Beach. Well, it was Mission Bay High School in Pacific Beach.

And then, when it came time to go to college, I was really not very well-prepared in terms of my possibilities. I think I was prepared academically. And I really didn't know where I should go. We didn't have money. I mean, we weren't poor, but we couldn't afford to go to Harvard, or places where it would be expensive.

And so I thought state school. And the University of California, at that time, had a very good state school system. And so I applied at Berkeley and Riverside, among other places. I think I applied to places like Harvey Mudd, too, which is a private school. But I didn't get into Harvey Mudd, because I wasn't smart enough, and we couldn't afford it, either.

INTERVIEWER: Oops.

SCHROCK: But it was just, I did it on a lark. And then I was accepted at several places. And Riverside was not too far away, 90 miles straight north of San Diego. And so I thought I could come home.

And it was a small place. It was just starting. It had been established for only a few years. And so I went there thinking, maybe I could get in on the ground floor in terms of doing research as an undergraduate, which I did my first summer, started.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, tell me about that. A chemistry professor sought you out? How did that--

SCHROCK: Well, it was after the first exam in, I've forgotten the number of it, but it's Chem 50, or whatever it was. And it was taught by a guy named James Pitts, who was an atmospheric chemist at Riverside. Back then, smog and pollution was a very big deal, because it would roll in from Los Angeles to Riverside, which was 60 miles away, every day around 3 pm And it would be awful.

And they really didn't know the basic problems associated with smog and how it formed. And so that was a big deal back then. And he taught this course. And so three of us that got the highest scores in the exam were called to his office.

And he said, you want a job? And I said, sure. So all three of us worked for him during the summer, that summer. And then during the year, I worked for him, and the next summer. And I may have taken one summer off to do something else. But I worked for him that whole time.

INTERVIEWER: That's great to get that research experience as an undergrad.

SCHROCK: Yeah, and I was on my own. I learned how to blow glass, and I made vacuum lines. And I worked with an infrared spectrophotometer. I thought I was going to be a physical chemist. So that's what I anticipated as I went through college, that I would be a physical chemist, not really knowing what a physical chemist did.

And most physical chemists don't make things like I wanted to make. So when I found out that that was true, I decided that I probably was not going to be a physical chemist. And that happened toward the end of my period in college.

I took an inorganic chemistry course from somebody named Fred Hawthorne. And he really opened my eyes as far as inorganic chemistry is, which is all of chemistry. Organic chemistry is a subset of inorganic chemistry, and so on. Everything is inorganic chemistry, all the elements. And so that's really the basic science, the basic chemistry.

INTERVIEWER: Let me ask you this. At the time when you were an undergraduate, were there certain big questions in chemistry? Or what were the things that people were-- you mentioned the atmospheric chemistry, and smog was a big question there. Were there other big issues in chemistry at the time?

SCHROCK: Oh, many, sure. Certainly a lot of biological questions. The structure of DNA had been predicted about 10 years before that. and also confirmed. And so everybody was wondering, how does DNA work? How do we make cells? How do they get differentiated? There's all that biological stuff.

And then physical chemistry, of course, was, as always in the 20th century, pretty important. And people were always asking physical questions, deeper and deeper physical questions. And organic chemistry, I remember one day in my physical chemistry course, actually-- I think it was when I was a senior. That would have been about '67. Maybe it was when I was a junior. The teacher came in, and he said, I've got a great thing to tell you. We've just found out how certain organic reactions work. And it's all explained by something called the Woodward-Hoffman rules. Now, Woodward and Hoffman were at Harvard at the time. And it has to do with why don't certain reactions work and other reactions work, either photo-chemically or thermally.

And so we spent the day going through the simplest of those problems. And it was a revelation. So yeah, a lot of things were happening. And they're still happening, just at a different level. Always more of them and at a higher level, maybe.

INTERVIEWER: So how did you-- you went directly from there to Harvard for graduate school, is that right?

SCHROCK: Yeah, so there was a teacher there named Jerry Bell--

INTERVIEWER: A teacher at Riverside?

SCHROCK: At Riverside, who was a physical chemist. And so we, my friends and I, thought, as I said, we were going to be physical chemists, because of the chemistry course that he taught. Which, he was a very energetic guy. And he really was a great teacher. And so that certainly affects people who are taking a course. And it affected us and made us think, well, we want to be like him.

And we got good grades. Jerry was from Harvard. So he decided that I maybe should go to Harvard. I was good enough to go to Harvard to graduate school. And so there had never been anybody sent to Harvard. It was a young college. That's not really hard to understand. But he decided that maybe I should apply to Harvard.

And so I did. And I was accepted. And it was pretty amazing, because Harvard was like the other side of the world, and I knew nothing about Harvard.

Now, these days, of course, people who go to graduate school, they go and they visit 10 or 12 schools. And they spend weeks doing this. And they grill everybody in the department, and so on. But I went to Harvard just totally blind, more or less. And it was a revelation. So it was exciting.

INTERVIEWER: I can imagine. So you were how old, 20?

SCHROCK: Well, I was 21.

INTERVIEWER: 21. So you're 21, and you're like, I'm going to grad school at Harvard, and you just show up in Cambridge.

SCHROCK: Right. Actually, I just turned 22. My birthday's in January, so I'd turned 22.

INTERVIEWER: Wow. Yes, that must have been pretty heady.

SCHROCK: Yeah. So that was '67. And so I drove across country and got stopped by the police, who noticed that I was driving somewhat erratically. And I told them I was just happy.

[LAUGHTER]

They said, yeah, sure. But then they believed me and let me go. They thought I was on something, I think.

INTERVIEWER: Right. High on chemistry.

SCHROCK: High on chemistry. And yeah, drove cross-country in my Volkswagen, I think it was, and arrived at Harvard. No, it wasn't a Volkswagen. It was a Dodge Dart.

INTERVIEWER: A Dodge Dart. Even better, even better. So when you got to Harvard, not having researched the department or anything like that, did you have a little trouble finding what you were going to study here?

SCHROCK: Oh yeah. Yeah. So I checked out all the people who were doing physical chemistry. And they were doing very good physical chemistry, molecular beams and things that were at the forefront physical chemistry. And Dudley Herschbach got a Nobel Prize, for example, for that work. And that's all excellent physical chemistry. But I knew something was missing.

And I just didn't feel like I was a physical chemist. Because very often you spend most of your career building an instrument. And then you tried your experiment, and it might or might not work. And then you wrote your thesis. And then you got your PhD.

I wanted to make things. So I was actually a little dejected. But I walked by an office where there was somebody who had just arrived at Harvard that I didn't know. I didn't know about this person. Well, I didn't know about anybody else, either.

But his name was John Osborn. And he was a student of Geoffrey Wilkinson, who won the Nobel Prize in '73, later, when I was at Dupont, and has written many books. And he passed away in '96.

But John was one of his favorite students, and a very successful one. And he was sent to Harvard by Wilkinson. And he had just arrived. And I was his first student. I turned out to be his first student. So I talked to him.

And he told me about all the sorts of things I used to do in my laboratory. I used to make things and crystallize things, and pretty colors of compounds. And I thought that was pretty neat. Catalysis, that's very big in my subsequent career.

INTERVIEWER: So that's where you first got--

SCHROCK: That's where I first learned about transition metals, catalysts, making metal compounds, which are catalysts for reactions, and then actually doing organic reactions with those catalysts. And in my case, then, it was hydrogenation of alkenes or olefins.

INTERVIEWER: Okay. That's interesting. So he's sort of responsible for bringing that into your life.

SCHROCK: Yeah, he was somebody in the right place at the right time for my needs. I don't know what I would have done without him being there.

INTERVIEWER: Interesting. So tell me about 1968.

SCHROCK: Hmm. Oh, yes. What about 1968? So that was-- are you talking about the summer of '68?

INTERVIEWER: Well, tell me what Cambridge was like then, and what you did.

SCHROCK: Well, that time was a very rebellious time, I'd say. So I don't know what time these various events occurred. I think in '68, the students occupied the buildings at Columbia. Later, they occupied the administration buildings at Harvard. There were demonstrations. There were a lot of things going on during '68, '69, and even '70. '69 was probably the worst.

In '68, I was feeling like I should see another part of the world. So after the spring of '68, after my first year, I had taken some classes, and I'd got started in research. And that was all fine. But I went to John Osborn. And I can just imagine a student of mine doing this in my group now. And told him that I was leaving for 15 weeks, and I was going on my world tour, which I did.

INTERVIEWER: And what did he say?

SCHROCK: He said fine. Well, he may not have said fine, but he let me go.

INTERVIEWER: Huh. I mean do you, with all this tumult going on--

SCHROCK: He didn't pay me.

[LAUGHTER]

INTERVIEWER: --all this turmoil going on in Cambridge, did it affect what was going on in the lab, or with your work, or the way people were thinking about work and how it fit in to the world?

SCHROCK: I don't think so. I don't think so.

INTERVIEWER: Why did you feel the need to go--

SCHROCK: To Europe?

INTERVIEWER: Yeah.

SCHROCK: I was born in Indiana. And I lived in California. So that was a taste of another world. And then I decided that, well, Harvard, that was Cambridge and Boston, pretty interesting, and that I really had to see some place else. Like Europe, I'd never been to Europe. I think I'd never flown in a plane. Is that right? I think that's right.

INTERVIEWER: Wow. So where did you go? All by yourself?

SCHROCK: All by myself, yeah. Well, I met up with people. But that was back when you could hitchhike. And there were books written about hitchhiking your way through Europe, and Europe on 5 Dollars a Day. Now it should be $50 a day or more. And there was a lot of hitchhiking. And that was it, back then. That's how you got around. Or you could take a train, get a Eurail pass, which is wimping out. It's the comfortable way to do it. Real people hitchhiked. So I hitchhiked my way around Europe. And I had a lot of interesting experiences.

INTERVIEWER: Wow. Was it a transformative time in your life?

SCHROCK: I think so. It certainly taught me about Europe. And I still have a lot of close connections and good memories. And I'm not European, but I certainly do love to go to Europe.

INTERVIEWER: When you came back, did you feel changed, older, different? Or did you just--

SCHROCK: I gained about 10 pounds. And I was quite tired. But yeah, I certainly felt like I'd been around. I went to France and Spain and Italy and Switzerland. And my mother's side is from Switzerland. So I visited the place where my great-grandmother was born, and things like that.

And I went to Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary. I even went to Hungary and Czechoslovakia, before the Russians invaded, by two weeks, fortunately. And then into Germany and Denmark, went north into Scandinavia, part of Sweden. I didn't go to Stockholm. Went up to Oslo and back down over through England, up through Scotland. So yeah, I went all over the place.

INTERVIEWER: Well, it's just interesting, because a lot of people seem, in that time, to go through that experience. But then they don't actually come back. They just sort of whatever, drop out or get into politics, go into some sort of alternate thing. But you came back to Harvard and picked up with your work.

SCHROCK: Oh yeah. I didn't intend not to come back. I just wanted to go out and see the world. And that's what I did.

INTERVIEWER: Good. And then something else happened the following year, 1969. I believe the date was November 16, is what--

SCHROCK: Yes, November 16. I think that's correct. I met my wife, Nancy, at a party in Somerville, and we hit it off. And so we were married in '71. But for a year and a half or so-- is that right? So there's November-- okay, a little more than a year and a half, yeah, we dated and went out. She would come over and throw stones at my window to get me out of the lab, because I tended to stay in the lab too long. And whenever I was really hungry and hadn't seen her for a while, I'd phone her up and we'd go out to dinner. And we had a time. Had a good time.

INTERVIEWER: She's not a scientist?

SCHROCK: She's not a scientist, no. Her undergraduate degree was in art history. And she later learned how to bind books. She's a bookbinder. And she has a lot of experience in that area, now works here at MIT. And she used to be at Harvard. She worked at Harvard for nine years.

INTERVIEWER: So you got married, got your PhD all around the same time.

SCHROCK: '71, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Okay. And then went on to a--

SCHROCK: And traveled to England. So got my PhD, got married, moved, traveled to England, all in the latter part of the summer of '71.

INTERVIEWER: Wow.

SCHROCK: And that was exciting, too.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. So tell me about your year at Cambridge.

SCHROCK: So that was a wonderful year. I was an NSF postdoctoral fellow. And so my salary was paid in dollars. But the value of the pound versus the dollar, the pound was $2.60, I believe, in dollars. It was extremely valuable. And I got paid in the lower currency, the dollar. So it was a struggle, I would say.

But we were young. It didn't matter. So we didn't have any money, but I could buy a car. I think I bought a car for 300 or 400 pounds. And we traveled around, and we did a lot of wonderful things all over in England. And the weather was sometimes agreeable, sometimes not.

I went to the lab. I could walk to the lab. And so I spent my time working pretty hard, but nothing really significant ever came of it. I think I published one paper.

And she worked in an architectural firm. And she became interested in architecture. Probably she was interested before that, but that certainly accelerated her interest. And she maintains that interest now, in architecture. So she's my guide whenever we go abroad, in art and architecture. It's really very nice.

INTERVIEWER: So after that was Dupont. Is that right?

SCHROCK: After that was Dupont. Well, the reason I had to go to-- I shouldn't say "had to go" to England. Sort of, that's true. So in 1971, when I got my PhD degree, there were no jobs.

INTERVIEWER: What do you mean, no jobs?

SCHROCK: I mean no jobs in chemistry.

INTERVIEWER: How can there be no jobs in chemistry?

SCHROCK: Well, if there's zero, that's no jobs.

INTERVIEWER: It just seems impossible to comprehend.

SCHROCK: It was a very tough time. I think there was one academic job for which there were 600 applicants, in Alberta.

INTERVIEWER: Wow.

SCHROCK: It's cold up there.

INTERVIEWER: Wow. It's just hard for me to imagine no jobs for a PhD in chemistry from Harvard.

SCHROCK: And industrial jobs didn't exist. So I had the very bad timing. So fortunately, I didn't go to Vietnam and managed to get through graduate school. That's another issue. But I didn't have any place to go. And so I managed, thank God, to get an NSF fellowship, and went to England, which was wonderful.

But then, there were not many more jobs in the spring of 1972. And so there was a guy who was on sabbatical there named Earl Muetterties, who was an associate director at Dupont, one of six associate directors. And he was there. He knew Jack Lewis, whom I worked for for a long time. And he managed to convince Dupont that he could take a sabbatical, even though that wasn't done at that time. And so he was there for six months. And so I met him there, and we talked, and so on. And he basically made me an offer to come and work at Dupont. And so that, I decided, was what I was going to do.

I looked around at other places. There were some academic jobs available at that time, and a few other industrial jobs. But Dupont was a place where it was really an academic environment. And they had terrific people. And I'd read many of their papers. And Muetterties was a real mover and shaker in that area.

And Dupont was really the premier basic research laboratory in the world. There were others, maybe six or eight others. There aren't any now of that type, where you could go and do whatever you wanted, up to a point, and for a certain period, be creative, be innovative, do something new. Which I think I did.

INTERVIEWER: Now, I want to talk to you a little bit about your work at Dupont. But before we go there, when you were going through this time of getting your PhD, and there was no jobs, did you ever think that you had chosen the wrong field? Or you're like, oh--

SCHROCK: Ah, but I didn't know there were no jobs.

[LAUGHTER]

And if you don't know you're going to fall off a cliff, then you don't know, right? So I never thought about it. I just did my work, thought about getting my PhD. And I know today, people think a lot about after that, and is this going to be the profession I want, and so on and so on. But I guess I just didn't do that.

INTERVIEWER: Well, it's good it worked out.

SCHROCK: So I just winged it, more or less.

INTERVIEWER: So you went to Dupont. And I might be mistaken, but that's where you started doing the work that would eventually lead to the Nobel. Is that--

SCHROCK: That's correct, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: --correct? Okay. So can you tell me a little bit about how that ball started rolling, there at Dupont?

SCHROCK: Yeah. So when I was in Cambridge, I worked on some ruthenium chemistry. And one of the ideas I had was to use a kind of molecule that's called cyclooctatetraene. Don't try to say that 10 times. Cyclooctatetraene dianion was a ligand that would stick onto a metal. People were interested in that particular ligand, it's an organic molecule, and what it could do. And I became interested in it. And I made some complexes of ruthenium when I was at Cambridge.

Then I came to Dupont, and I decided that I would continue that work. But Dupont wasn't interested in ruthenium. They were interested in what we call early metals, things in Group 4 and 5, things that were used as catalysts to make polymers.

So polyethylene and polypropylene were discovered in the early '50s. And still, in the early '70s, people were very interested, since it was obviously going to be a huge market, and they were right, in other ways of making polymers from olefins. Olefins, ethylene , propylene in particular, come out of petroleum crackers in large quantities. So they're really cheap.

INTERVIEWER: And the issue was to make the process simpler. Is that why they were interested?

SCHROCK: Well, maybe to make a catalyst that was better than anybody else had, and therefore, you could patent it. And therefore, you had an edge. And you made a better product, and it was cheaper. And I convinced them that I looked around at some of the metals in Group 4 and 5, so you have titanium, zirconium, and hafnium, and vanadium, niobium, and tantalum. And I thought about tantalum chemistry, because another person in the lab named Ulrich Klabunde had done a little tantalum chemistry, made tantalocene bis(cyclopentadienyl) complexes, trihydrides. Sorry, too much chemistry here.

INTERVIEWER: Nope, bring it on.

SCHROCK: And so he was talking to me about tantalum chemistry. And I said, hmm, tantalum. That's an interesting metal. I wonder if anybody had done organometallic chemistry-- metal-carbon bonds of some sort, alkyls-- on tantalum. And then I said, well, maybe I'll check that out.

And I checked it out. And it turns out that somebody named Juvinall, who I've never seen publish anything else, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, G. L. Juvinall, had made trimethyl, three methyl groups, tantalum dichloride, so a very simple compound. Beautiful synthesis, 100 percent yield, and it had metal-carbon bonds in it. And that was the only thing I could find.

And so I took that and added the cyclooctatetraene dianion into it and made a tantalum trimethyl cyclooctatetraene complex. And it was blue, beautiful color. I don't think it's been used for anything. But I soon got diverted. Because what happened was that we had, I guess they were, what were they called? Well, advisers or consultants, that's what they were called, so full-time consultants at that time. And one of them was Geoffrey Wilkinson. And so--

INTERVIEWER: Comes back around.

SCHROCK: Yeah, there he was. So he came in 1973 and told us, he would usually give a lecture and then talk to us about what we were doing and give us advice. So in 1973, he came and gave a lecture at Dupont. He lectured at MIT, I know, probably at Harvard, probably other places. He didn't travel much, but sometimes he would do that. Didn't travel and lecture very much.

And he told us that he had just made tungsten, which is right next door to tantalum in Group 6, with six methyl groups on it. That's the maximum number you can have around tungsten. And it was a compound. You could isolate it. People thought that metal-carbon bonds were weak, and that you couldn't actually make compounds having metal-carbon bonds, that they would fall off, and you'd get radicals. Well, that turned out not to be true.

And I thought that was really interesting. And so I looked at tungsten, six methyl groups, tantalum, five methyl groups. I thought I would make tantalum with five methyl groups around it, which I did. And I noticed in Wilkinson's-- you have to write an autobiography as well as your description of your research. And at the bottom, he put in a footnote. And he said, he told the world in his address at Stockholm about hexamethyltungsten and other things. And then in a footnote, he said, pentamethyltantalum has recently been made by R. Schock at Dupont.

So I made that. It wasn't very stable. But it was a lot of fun to work with it. And then I decided, how do I make it more stable?

And so the way to make it more stable is, a methyl group is just C, H, H, H, with three protons on it. So it's very small. So to make it bigger, make each of those five groups bigger, so that they would not decompose in what we call a bimolecular fashion. It would be stable as mono-atomic species. They wouldn't decompose in that way. And fortunately, I could do that.

And then one experiment I tried failed completely. I could not make the pentaalkyl. Because that pentaalkyl, almost certainly an intermediate, didn't decompose bimolecularly. It decomposed intramolecularly. So within the molecule, it would decompose and spit out neopentane. Turned out it made a metal-carbon double bond. And then that compound was incredibly thermally stable, and a totally new type of compound. And so that was pretty interesting.

INTERVIEWER: And that was a mistake that led to that.

SCHROCK: It wasn't a mistake. It was a split in the road.

[LAUGHTER]

INTERVIEWER: Sorry.

SCHROCK: It wasn't a mistake. No, it was a fortunate result.

INTERVIEWER: Fortunate result, okay.

SCHROCK: But, well, it was pretty obvious that it was a really interesting new species.

INTERVIEWER: Well, that's what I was going to ask you. At that moment, did you say, huh, this is big. Or--

SCHROCK: I did, in my own way. I went home, and I told my wife that I think I'd done something interesting.

INTERVIEWER: And she said, that's nice, dear. What are we having for dinner?

SCHROCK: Yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

Well, no. No, she asked me, and I told her.

INTERVIEWER: Huh, wow. Wow, so that's interesting. So right at that moment, you said, aha. And that almost has become a key component of your life's work.

SCHROCK: Yeah, I still do that.

INTERVIEWER: And did you think--

SCHROCK: Forty years later.

INTERVIEWER: --at that time that that-- or did you just think, huh, interesting. Or did you think, wow, this is--

SCHROCK: Well, two things. So there was a guy named Fisher. So I made a metal-carbon double bond of a different type. And a guy named Fischer had made molecules in about '66 that he called Fischer carbenes, having metal-carbon double bonds in them. But they were of a different oxidation state. I won't go into details. They weren't of the type that I made. And that's number one. So they were interesting new metal-carbon double bonds, not single bounds.

And then, met-uh-thee-sis, or metathesis, was in the air. So it was discovered at Dupont, actually, in 1956. So about 15 years went by before I, at Dupont, came in one day when Earl Muetterties, an associate director, was in the laboratory taking something out of an oven that was a tube. And it had some black compound in it, black something. I don't know what it was.

And I said, oh, good morning, Earl, and how are you, and what are you doing, because he's not supposed to be in the lab. He's an associate director. And he said, I'm making a metathesis catalyst. I said, what's that? And he said, it's a very interesting reaction.

I don't know if he told me that I should go off and do metathesis. But it caught my eye. And if you're this guy who's at the top was in the lab making something that he thought was interesting, the wave of the future.

So I started to read up on it and find out how it works. And a lot of other people were interested in finding out, I found out, how it works, people like Bob Grubbs, with whom I shared the prize, and Yves Chauvin, a Frenchman in a polymer institute, and Chuck Casey and Tom Katz. And a lot of both organic and inorganic people were interested in the mechanism of this strange reaction, really a fascinating reaction, where you take carbon-carbon double bonds and just take them apart and rearrange them.

They're very strong. Single bonds are very strong. Double bonds are even stronger.

So how does that happen? That was the question. It involves a catalyst.

INTERVIEWER: So it seems to me like Dupont was a very fertile place for you. And it has all this, gave you this lab. You could do the work that you wanted. You have these big questions

SCHROCK: I could buy anything I want, more or less.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, you're satisfied.

SCHROCK: That's important.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, right. All the equipment you want, space. But then you left.

[LAUGHTER]

SCHROCK: Yes, I left. So I left because I wasn't sure that I wanted to be there forever. And I went there because it was a good place, but I really think I wanted to be in academics. But it was a very fertile place, as you point out. And I had the freedom to buy what I want, really, within reason.

And I was going to say, this is important, because of these big things that you put on metals, big alkyls-- everybody else who was interested in this, which included Geoffrey Wilkinson, by the way, had used something called trimethylsilylmethyl. It has a silicon, in place of a carbon. And that was a big group, but it wasn't the right size, just the right size. There's another thing called neopentyl, which has a carbon there instead of a silicon, that is similar, but very expensive.

So most people buy the cheap one. But I was at Dupont. I said, I'm going to buy 100 grams of neopentyl chloride and make a zinc reagent. I'm going to do neopentyl. I made that choice, number one, because the trimethylsilylmethyl work didn't seem to be panning out. Other people were working on it. And I could work in an area that nobody was working in, neopentyl. More expensive, but I was at Dupont.

INTERVIEWER: Well, why--

SCHROCK: So why did I leave?

INTERVIEWER: Yeah.

SCHROCK: Well, they changed two things. So my immediate supervisor, George Parshall, at some point, I can't recall when it was, probably during one of our reviews at work every few months, six months, let's say, he said, what are you going to do next? I said, gee, I don't know. Well, have you ever thought about academia? Maybe you should think about getting an academic job. and I said, that's what I always wanted to do. And I found out later, he also told my other supervisor, PhD supervisor, John Osborn, that maybe Dupont wasn't for me in the long run, or something like that. So--

INTERVIEWER: I just wonder. Because it seems like the actual lab work and the synthesis of the molecules gets you really excited, and you really enjoy it. So I was wondering--

SCHROCK: And I did it all myself, more or less.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, that's what it sounds like. So what would be the pull of academia? When you say you were always interested in academia, what about it interested you?

SCHROCK: Well, I could have lots of students doing all the work for me. Or with me, I should say. And I could teach, and I would have more vacation, maybe. And I could travel to Europe and give lectures, and do all the stuff that I wouldn't be able to do at Dupont.

So I was advised, maybe the time was right for me to do get an academic job. I said, well, I've got to find one, first of all. So that was late in '74. And two other things happened.

Before that time, soon after I got to Dupont, in late 1971, no, '72, Earl Muetterties announced that he was leaving. And he went to Cornell. And he spent about seven years at Cornell. He wanted an academic job, too.

He thought, he can do this. He ran a fantastic group at Dupont. He had all the wonderful people like me, Ulrich Klabunde, Fred Tebbe, and so forth working for him. And he said, well, that'll be a piece of cake. He found out that students weren't the same as the people I just mentioned. You have good students and maybe not-so-good students. So he wanted to go to academia, also. So that was one thing.

And then the other thing is that they changed in 1974, I think, of the department, from Central Research to Central Research & Development Department. And so it was always in the wind at that time that basic research was very expensive. You guys cost too much money. You discover useless things like metathesis. And we just can't afford you. And that ultimately was the decision made in virtually every company around the world, that they could not afford running basic research labs containing a couple of hundred people, who just are having fun and making discoveries, but it's very costly.

INTERVIEWER: It's amazing now that when you look at the advances that have come out of all the basic research and all those labs, to think that it's--

SCHROCK: Well, look at metathesis. Okay, then I became interested in finding a job. And then my first interview was in the fall of 1974. And I was not made an offer. And so I was a little dejected about that.

And two other things, oh, consultants. One of the consultants at Dupont was Barry Sharpless. So Barry Sharpless was at MIT. He was interested in osmium chemistry. He ultimately received a Nobel Prize in 1971. At that time, he was a consultant. He was a consultant in the '70s, the period I was there. And I had just made this discovery in 1974. And I think he came through in the fall of '74.

And I invited him. We could invite people to come and give a talk, if they weren't scheduled to be a consultant. And I told him what I was doing. I'd just made this fantastic new compound.

There's another person named Grant Urry who was at Tufts, who was a consultant. And I told him about it, and he got very excited. And he said something like, you just made a metallic Wittig reagent. And he started jumping up and down in his chair. And so I did some of the experiments he suggested, and they worked out.

And I told Barry Sharpless about them. He was interested in metal-oxygen double bonds. I was interested in metal-carbon double bonds, these new types of carbon double bonds. And I don't know if I had been rejected or not made an offer at that time or not. Maybe I had not been made an offer and told him about it.

So he went back to MIT and said to people like Alan Davison and Dietmar Seyferth. And he said, there's a great guy at Dupont who maybe we could attract. And so they asked me to come up and give a talk, which I did. And I don't remember much about it.

But they could see that this was something that maybe was going to turn into something big. Who knows? But clearly it was something new. That's what you want when you hire somebody, that they have something new that they've just discovered or you think they're going to discover.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. And it seems like this guy can come here and build a lab and have a lot going on.

SCHROCK: Well, study what you just discovered. Make it something. Make it into something.

INTERVIEWER: Just one more question before the break. Do you remember any impressions of MIT at the time, in 1974 or '75?

SCHROCK: That would have been probably the spring of '75. Yeah. Beautiful setting, very imposing, buildings all connected, can't find my way around. Right next to Boston, in Cambridge, not too far from where I was a graduate student at Harvard. And I had memories of that time, of course, and so it was like coming home.

And a great department, a great chemistry department. And of course the students. There was a reputation. MIT had a reputation. I didn't know that at the time, maybe, in the way I do now, but it certainly had a reputation, as did and does Harvard and certain schools. And so I felt like it was really a good place and had a good inorganic and organic, and good chemistry department all around.

INTERVIEWER: So you arrive at MIT in 1975. And how is MIT different than other places you had worked?

SCHROCK: So I was a graduate student at Harvard, I got undergrad done at Riverside. I would say, well, it was known as an engineering school, still is. And so I knew that. And so chemistry was a small department, a relatively small department. I knew it was full of a bunch of incredibly talented students, probably most of them male at the time. Or that was just the beginning of admitting, I'm not sure about this, but admitting women in larger numbers. It was a monolithic place, obviously, the way it was built, all the buildings connected. It looks kind of like the Pentagon. So there were some obvious things that I realized just on the surface. But I knew it was a great place. I knew there were some great people here, and that I was going to be part of it. So that was really exciting.

INTERVIEWER: Now you've been here for 36 years.

SCHROCK: I guess this summer would be my 36th year, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Is there anything you've observed over that time, any-- or what are the biggest changes that you've seen? And the corollary is, is there anything that hasn't changed at all in that time?

SCHROCK: Yeah. Well, the most changes, that's certainly buildings. That's always true, expansion. Most of the buildings I see around me now, of course, weren't here when I was there, when I came to MIT.

And then changes in admission, and of course, admitting more women, more foreign students, underrepresented minorities, and so on. And attracting not just the best students, but a certain fraction of the best students, and then others with broader interests, and so on. So it became a real university, I would think, very much less oriented towards just, you know what I mean, the focus on the hardcore sciences and math. They did have good departments at the time. And I found out later, of course, it still does. It had the first school of architecture, in fact, in the US. Architecture, other departments, music, good music department, not just the hardcore sciences.

INTERVIEWER: Is there something you particularly like about MIT? And is there anything you dislike?

SCHROCK: I see it as a very humanitarian, friendly place. My wife worked for Harvard for nine years. She has a different-- she has a view of Harvard. She's worked here now at MIT. She actually worked at MIT in '78, in the architectural library. So she worked there, and then we had children, and so on. And then she came back through Harvard, and now here again. So she also agrees that it's a very humanitarian, egalitarian place, and full of very talented and interesting people.

INTERVIEWER: So, when you say humanitarian, you mean it treats its people well. Or do you mean a humanitarian as its role in the world? What do you mean?

SCHROCK: No, I mean it treats its people well. And they treat each other well. It's not like you have a privileged class, and you're not one of us, and so forth. And that's very much appreciated, I think by everyone.

INTERVIEWER: Is there anything that's ever rubbed you the wrong way about MIT?

SCHROCK: Oh, does it rub me the wrong way? I don't think so. We're very highly regarded in the world. Especially abroad, in many ways, MIT is a bigger name than Harvard.

INTERVIEWER: And if you think about your time here, is there an MIT moment? Or is there images in your mind of particular things that have happened, and you think, wow, only at MIT, or anything like that?

SCHROCK: Yeah. I guess the pranks, the, what are they called?

INTERVIEWER: Hacks.

SCHROCK: Hacks, yeah, very famous. I saw a few of those.

INTERVIEWER: Is there one that stands out in your mind?

SCHROCK: Not in particular. The one that, I think it was the Harvard-Yale game that MIT set up. It's a balloon that came out of the grounds. That was a pretty good one. But there are lots of other good ones.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. Yeah, I'm quite fond of those.

SCHROCK: I was here for the pumpkin on top of the dome, and all that.

INTERVIEWER: I remember that one, too. That was great. So one more MIT question, MIT seems to have a view of its role in the world, of engineering useful solutions that will help the world. And do you feel that that's a role that MIT takes seriously? And do you think about that in your work?

SCHROCK: Well, I think about the role of my work and what being at MIT can do for me and what my work can do for them, and so on. I don't connect it to engineering, because I do fundamental type stuff. But I do things that have utility. And I guess I learned that from starting in my graduate days and my days at Dupont.

And of course, you can only get money these days if you work on something that's actually going to prove useful. And that's perfectly understandable. So useful in some way, so that's why I continue to do what I do. And so yeah, I think about the influence of what I do and what I've done at MIT on the world at large quite a bit. And I'm still thinking about that, working towards that end.

INTERVIEWER: So let's talk about the work for which you won the Nobel Prize. So we talked a little bit about what you did, how it started at Dupont. So how did the work continue here? And there was a breakthrough in 1990, I believe, something like that.

SCHROCK: Yeah, mid-'80s, something like that.

INTERVIEWER: Okay. In other words, talk to me a little bit about that?

SCHROCK: So I worked on tantalum at Dupont. And the catalyst that did this fantastic new reaction contained molybdenum or tungsten. Tungsten's right next door to tantalum, molybdenum above, and then next to tungsten is rhenium. Those three, molybdenum, tungsten, rhenium, were the metals that were in these black boxes. You throw a bunch of things together, and you get a solution. You throw in the olefins, and you get this fantastic reaction. But nobody really knew what was in there.

And so in the beginning, I took my tantalum chemistry that I had started and tried to find out if this has any relationship to the real thing. Because tantalum is not in that list of metals that I just said. So you can't throw tantalum in and have it do what these other metals would do. So there's something magic about molybdenum, tungsten, and rhenium. But nobody knew what it was.

And so I took tantalum to the point where I could show, make it through synthesis and variations, make it do the reaction. It didn't do it very well. It did it like 30 times. But it did it.

So I said, well, now I just have to find out what kind of tungsten compound. That's the next step to the right. It's like a dance. Go one step to the right, one step up. What type of tungsten compound should I make?

And so I tried to make one that I thought would be the one. And of course, I didn't get that. Something else happened that showed me what was the type of tungsten compound I should make, because we could make that one work pretty well. And then, we did a lot of variations and changed things, and also moved up to molybdenum, and also moved over to rhenium, and made all of those work, all three of them. And that's continuing today.

Most of that happened, I would say, between about '80 and '85. It was a very heady time. Or maybe a little bit later, '86, the first what I call well-defined catalysts that you can put in a bottle, you can be assured that they're going to react when they're supposed to react, were discovered and published here at MIT.

INTERVIEWER: And were these catalysts immediately snatched up by industry? Or were they--

SCHROCK: Oh, no. No, they didn't care.

[LAUGHTER]

Well, I don't think that the reaction had reached a point where they thought it could be useful. These things sometimes take a long time. A lot of things take a long time.

And it wasn't the answer to all their prayers. In terms of organic chemistry, they had hundreds of reactions, catalytic or not, to use. And okay, somebody discovers another cute reaction. Does that have any relation to organic chemistry or not?

And so this is where Grubbs comes in. So he's an organic chemist, and I'm an inorganic chemist. So I am interested in the metal, making the compounds, getting them characterized, and so on. And he's interested in organic chemistry.

So he did some work on these new compounds I discovered in the mid-'80s. And then he always wanted to make compounds that were not so sensitive to water and oxygen, like these new compounds that I made. And so then they could be applied by the average organic chemist. He or she could open it up in the air, do the work, and make organic molecules. And he succeeded in doing that in the early '90s. And so he made them ruthenium carbenes, as they're called.

And so now ruthenium, molybdenum, and tungsten are the big three. Molybdenum and tungsten are mine. Ruthenium is his. And that's the way it is.

So the point is that he took these compounds, then, that everybody could use, made them commercially available, actually started a company in the mid-'90s. And he's always been very entrepreneurial. And give these compounds away to the average chemist to do this, that, or the other reaction and move organic chemistry forward using these compounds.

INTERVIEWER: Interesting. And so was there a point along the way where you started to think that this work was Nobel Prize-worthy?

SCHROCK: That was probably in the early '90s. I received a few awards, more than a few awards. But in 1990, I received what's called a Harrison Howe Award, which is an award of the ACS, American Chemical Society's, Rochester section. And I didn't know much about it.

But I remember being at dinner with Professor Eisenberg and others at Rochester, University of Rochester. And he said, we're very proud of our record in awarding the Harrison Howe Award. And I said, what record? And he said, the number of people who go on and win a Nobel Prize. And I felt like saying, well, why did you give to me, then? But he said, we think you are going to win a Nobel Prize. So that was the first time I had heard anybody say that.

INTERVIEWER: And what did you think when he said that? Did you think--

SCHROCK: I figured, wow, that's interesting. And then as the years wore on, you know, more and more people-- Bob Grubbs, of course, was doing all this work. And everybody started using these catalysts. And so olefin metathesis became pretty well known.

And then by about 2000, 10 years later, it had really become well known. And lots of people were saying, this is really of a Nobel Prize. This is changing organic chemistry. I wasn't changing it very much at the time, because I'm still working away at my molecular level and not applying it to organic chemistry. But that, too, has changed in a very big way in the last couple years.

So Bob started this company in the mid-'90s and popularized the catalysts. Of course, they want to make money, so they approached a lot of industries. And there are some industrial processes now based on metathesis, both ruthenium and molybdenum or tungsten, some of them very, very big, many of them involving these old catalysts that aren't very fancy, not these new ones that we made, just basic, run-of-the-mill catalysts. But they work, and continue to work for a long time. And then it started to have an effect in a very basic way, sort of commodity chemicals.

Right now, they take ethylene, which is dirt cheap, and butenes, which are four-carbon olefins that come out of crackers. And they metathesize. They chop each one, put it together, and they get propylene. And because propylene's much more expensive than ethylene, and it's cheaper to make propylene from ethylene and butenes than it is to buy propylene. So now they're putting up these huge plants all over the world now based on generic, old-fashioned tungsten catalysts, not anything I did, because they're too expensive and too fancy for this reaction. And they're still building these plants.

Meanwhile, organic molecules, pharmaceuticals and so on, people started to tell how can we use this reaction, because it does wonderful things. And there's no alternative, really, in terms of the numbers of steps. You can do one step instead of 10. So syntheses that were previously 15 or 20 steps became seven or eight. So if you're going to make and sell something, that's a huge savings. And so a lot of people began to be interested in making their product using metathesis, and still are.

INTERVIEWER: Interesting. So tell me about actually winning the prize. How did you hear about it? Did you get a phone call at six in the morning? Is that how--

SCHROCK: 5:30.

INTERVIEWER: Could you just tell me about the day?

SCHROCK: Yeah, so that was October 5, a Wednesday. And in Sweden they have a final meeting where they more or less rubber stamp what they had already decided. I guess it starts at nine in the morning. And by 11:30 or so, it's official. And of the 10 or 12 buttons that they could push, they push number 3. And everything starts rolling. And that includes calling the recipients. So if it's 11:30 in Sweden, it's 5:30 in Boston. And so the phone rings at 5:30 in the morning.

Now, I don't think I've ever had a phone call at 5:30 in the morning. So you knew it was either possibly good news, because I knew that the Nobel Prize was going to be announced that day, or bad news. And I didn't think my mother was ill or anything.

But my wife picked up the phone. Upstairs, she picked it up upstairs. And I picked up the phone downstairs and didn't push the button. So I couldn't hear what was going on.

So she actually talked to an operator first. And then she said, I think you better come up here. So I did. And she said, are you so-and-so? And I said, yeah. And she said, there's a member of the Nobel chemistry committee who wants to talk to you. I had no idea what he wanted to talk about. Yeah, it was all very quick. And I said thank you a lot. And it's a haze, a fog. And then he said, get ready for a very busy day. And of course, all the other buttons are pushed, and pretty soon it's international.

INTERVIEWER: Wow. So what did you do? You hung up the phone. And what did you do?

SCHROCK: Picked it up again, because it rang.

[LAUGHTER]

And it was somebody in South America who wanted to chat to me about what I had discovered. And I think they even hooked me up with Bob Grubbs, who was in New Zealand, where it was 1:30 in the morning. And we said hello. And I think they recorded that, and so on. And then that took maybe 10 minutes or so. And then I hung up the phone again. It rang again, so I picked it up again. This time, it was Russia. I can't recall.

So finally, my wife said, don't pick up the phone. Or leave it off the hook. Because I was in my bathrobe, and about an hour and a half had gone by. And I had to be at MIT for a 10 am press conference. Okay.

INTERVIEWER: How did you know that? Did they tell you that?

SCHROCK: How did I know that? I think somebody must have called me and told me. I think, yeah. I don't recall. I don't know how I knew that.

INTERVIEWER: So did you manage to call anybody and tell them?

SCHROCK: Yes, on the way to MIT, I called my mother, who was still alive at the time. And I told her that I had just won a Nobel Prize.

INTERVIEWER: And what did she say?

SCHROCK: She said, a Nobel what? A what, she didn't say a Nobel what. She said, a what?

[LAUGHTER] And I said, a Nobel Prize. And then she really got excited. She was 92. Actually, she was, I think, at that time, since her birthday's late October, she was 91. But she went to Stockholm.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, she did. That's nice. That must have been huge.

SCHROCK: It was tough. She was 92 and not that well. But she insisted, so.

INTERVIEWER: That's wonderful. So the rest of the day, what happens? Did you--

SCHROCK: Okay, I got to MIT. And my colleagues were already drinking champagne. It was like 8:30 in the morning. And I had to give this press conference at 10 am. And there was a lot to do, a lot of people coming and going, and celebrations, and so on.

And then we had a press conference in the Moore room, which is right up from my office on the third floor of Building 6. Yeah, they had to set up the cameras there. And so that took some time. And then, yeah, at 10 AM, Nancy and I walked in. And everybody was there. And they were sending in questions from all over the world. And I don't recall. There weren't that many. But there wasn't much time. But I just had to answer questions and thank people and so on.

And of course, Susan Hockfield had just started in 2004 her tenure as president. And Frank Wilczek won the Nobel Prize in 2004. And then I won the Nobel Prize in 2005. So she was okay with that.

[LAUGHTER]

Okay, then we didn't have a Nobel Prize for a few years. But she was very happy. And I was very happy. Oh, and then I had to give a talk.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, they sort of throw that right at you, don't they?

SCHROCK: Well, it's tradition. Four in the afternoon, I found this out. You have to give a talk, a chalk talk in 10-250, which holds about 400 people. And I wasn't prepared, of course. You can't be prepared, because you're not allowed to use slides or anything.

So at lunch, since I couldn't drink wine and celebrate, I spent my time jotting down a few notes, an outline, basically, on a napkin of what I would talk about. And it was more or less historical, somewhat like I've talked about here. So it wasn't difficult. But all chalkboard, and some of that you see around MIT, either still pictures or movies of my talk.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. That's really neat.

SCHROCK: Yeah, 10 am. And then we went out to dinner, and I did celebrate with wine.

INTERVIEWER: Good, finally.

SCHROCK: Finally.

INTERVIEWER: Winning the prize, how did it change your life? Or did it change your research in any way? Did it change the type of research you did? Or does it open doors for you? How did it do anything?

SCHROCK: Well, it certainly opened doors, all kinds of doors just because I have a Nobel prize. So naturally, around the world in most civilized countries, people know what a Nobel Prize is. It's the most famous prize there is.

And they might not get the subject right. I keep being congratulated for winning the Nobel Peace Prize. I have to tell them it's not what I won. It was in chemistry, and they seem a little disappointed by that. But I'm used to that.

So around the world, I think everybody recognizes it. And in certain parts of the world, really, it's like you're royalty. And so it really changes the way you are received in much of the world. It opens new doors, new possibilities, whether it's consulting or this, that, and the other thing. It certifies you in a very big way. So that's a big change.

INTERVIEWER: Were there any downsides?

SCHROCK: I wouldn't say there were any major downsides, no, except, well, not everybody is happy for you. But I think most people were happy. It's like being president. As long as most people are happy, that's-- because there are a lot of contenders out there, and people who maybe disagree. And maybe I shouldn't have gotten the Nobel Prize. So that's the way it goes.

INTERVIEWER: Have there been any surprises for you since winning the Nobel Prize? Anything, I don't know--

SCHROCK: Well, there's always what do you do after the Nobel Prize, scientifically, but--

INTERVIEWER: Yes.

SCHROCK: Do you just wind down your group, and you're already looking forward to retirement, and so on? Or do you choose another problem, you go off and cure cancer or something? That's just, you can't do that. You can't choose today, I don't think anybody can just choose a whole new field and expect to compete with hundreds of other extremely talented people.

So fortunately, I had teamed up with a guy named Amir Hoveyda at Boston College. And he's an organic chemist. And in 1997, we met at a conference, and I told him about some recent results that could really influence organic chemistry a lot, new results in metathesis. And he's a very energetic guy, and I think he said, well, you want to do something? Or you want to collaborate on this? And I said sure, let's do it.

So we applied for some money and continued to work together. And then that first grant didn't get funded. But the next one, in 1998, was funded by the NIH. And we have just been told that we got our, I hope, five-year NIH grant renewed. That is going to be, I think it was the 13th year. So after five more years, it'll be 18 years that we collaborated.

So he and I have, one plus one equals five, I think, as far as I'm concerned. Because neither one of us could have done separately what we did. We've really done some tremendous work in the last decade since we met, and then, in particular, in the last couple years.

So about two years ago, we started publishing some really major breakthrough papers. We just submitted another one to Nature, which is the premier journal in science. And we've got several in Nature now. And that gets a lot of press. So people are starting to realize what's going on. And we're really changing the way organic chemistry is done at a very sophisticated level, pharmaceuticals, making drugs, and things like that, with the discovery of a way to make double bonds that have one of two possible structures.

See, we won the Nobel Prize before it was possible to control the way, let's say you have two groups on a double bond, they can be on the same side of the double bond or on opposite sides. And those are two very different double bonds, different structures. And usually you get a mix of the one that's trans being about 3/4 or so, or 80 percent, and the one that's cis being 20 percent. And the one that's cis is the one that you find in nature, and the one that's really more valuable in many ways in organic chemistry. And we, just a couple years ago, figured out how to make olefins selectively with that structure. And that was the first time. And it can't be duplicated by ruthenium, at least not at the same level. There's been a very recent paper, but-- and we actually started a company based on that.

INTERVIEWER: I was going to ask you about that in a second. It's interesting. Do you think in the long run that your biggest contribution will end up being the work for which you won the Nobel, or this current work?

SCHROCK: Well, this is very closely related, okay?

INTERVIEWER: Okay. So it's all building on--

SCHROCK: Yeah. It's still building on the same theme. I've done one other thing that I would consider pretty important work. And that's to reduce dinitrogen all around us to ammonia at room temperature and pressure with protons and electrons. I was the first one to do it, after 40 years of attempts to do it. It'll probably never be practical.

There's a process out there called the Haber-Bosch process, which is the most successful industrial process, probably, in the 20th century, where you make ammonia 10 to the eighth times per year, I think. So we're never going to compete with that. But in terms of scientific achievement, I would say that's my other significant achievement. But this work is based on still the Nobel Prize, and, well, the subject matter is the same.

INTERVIEWER: So tell me what the company-- I wrote down, XiMo?

SCHROCK: XiMo, yes.

INTERVIEWER: Tell me, tell me--

SCHROCK: XiMo, X-I-M-O, XiMo.

INTERVIEWER: Is this your first--

SCHROCK: M-o is the symbol for molybdenum, you see.

INTERVIEWER: Okay, right. And what's the X-I?

SCHROCK: Well, E-X-I-M-O in Greek, I think, has a meaning of catalysis. So we dropped the E.

INTERVIEWER: I see. All right. That's cool.

SCHROCK: And you've got to have an X in there. So we got the X there.

INTERVIEWER: Is this your first entrepreneurial venture?

SCHROCK: It's my first, yeah. I think Bob Grubbs, as I said, was a very entrepreneurial guy. So he's started, I don't know, four, five, six companies.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. So you've seen that happening at a distance, and--

SCHROCK: Well, that's what he wants to do, not based on metathesis, all of them, on other things. But this is my first.

INTERVIEWER: And how--

SCHROCK: How's it going?

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. How do you like it. Is it--

SCHROCK: Well, it was founded in October. And we've got very good people. It's a Swiss-based company. And we've got people involved, both scientific people and businesslike people that are very experienced, very well known, very well connected. And we're just putting out our web page now, finishing that.

And so it's been less than a year in terms of since we founded it, in October. Although we'd been thinking and preparing about a year before that. So it's going on two years since we started putting this together.

And it's been an enormous job. I had no idea. I thought if you founded a company, you just went out. People threw money at you, and done. Right? No, not really. It's really hard work, legally and just in every way. It's really hard work.

INTERVIEWER: MIT has quite a tradition of this happening. Have they assisted you in this in any way? Or do you feel like, I don't know, it's in the air here or something?

SCHROCK: It's in the air, but they make it very clear, as they should, that MIT is separate from whatever you might do with what you discover and patent at MIT. You discover something. You patent it. And then if you want to start a company, okay, your people can come to our people and license the patent. And that's the way it's done. And of course, you can't have anybody in your labs associated with the company. And all that is strictly forbidden, which is the way it should be.

INTERVIEWER: So that just leads me to a question about your work style or your daily life now. What's an average day like for you? Is it mostly in the lab, teaching, email, working on the company?

SCHROCK: I guess it depends on the time of the year. Now, it's pretty easy-going, because I'm not teaching. And I commute with my wife. I commuted in today. So she comes in at the same time. We go back together. and it's very nice.

And usually, I'm working on papers in the summer. So a lot of things build up over the year that I can't complete. And people leave, they get their PhD and they leave about this time, or maybe later in the summer, in either one, will leave. And so projects will change, and what seemed important a year and a half ago maybe isn't so important.

And so I have, then, the new students coming along. And I've stopped accepting new students now. So i won't take any more students. But I still have six, and about six postdocs. So six students, six postdocs. And I have to move those chess pieces around to make sure that the students get a good start, and that the postdocs are making progress. And I do that sort of stuff in the summer, too.

I clean up my office. I throw out all the stuff. I give an interview. I had to plan my travel.

I don't do a lot of traveling in the summer, but usually there are three or four conferences. Sometimes I extend that, as we're doing to Brazil for our 40th wedding anniversary. So got to plan all that. And it's only three months during the summer.

And then the academic year is much different, I would say, especially if you're teaching. And there are faculty meetings and other kinds of meetings, and visitors, and people who come here to talk, and going out to dinner, and just a lot of things going on. On top of that, there are external things, like now, this company wants me to go over and try to entice companies to become our partners, so we can develop methods that they are going to be able to use to patent and to sell a product.

And then I was involved in a legal case that took up a lot of time. That happened in March and April and May of this year. And fortunately, I wasn't teaching this spring, otherwise it would have been really impossible. So that's it. And I try to have a normal life, otherwise, in between. Which I do.

INTERVIEWER: What are your main activities outside of work? Do you still do woodworking?

SCHROCK: You know, I haven't done woodworking in a while. Last time was last Christmas. I made a bunch of Christmas gifts, earring holders. Nice to give to my two daughters-in-law and my wife. But I still have other projects sitting down there that I haven't finished. And I've just been very busy.

Again, I haven't been able to enjoy music as much as I used to. I used to play and think about music a lot, not play myself, but listen to. And now I just turn it on, but I don't focus on. I try to stay fit, so I spend some time doing that. Try to garden, I like to garden.

I've been helping out my younger son with his house. He bought a house in Medford. So we redid the kitchen and the dining room, basically gutted it. And he put it back together. He was a contractor, and I was one of the workers. And we're still working on it now, the back porch. So it's been a busy time. So there's always something.

INTERVIEWER: Very full life

SCHROCK: There's always something.

INTERVIEWER: Tell me, you've had a very successful career in science. And you've guided a lot of graduate students and postdocs. Are there any things that you see-- or what do you think makes a successful career in science? Or how do you guide people toward having a successful career in science? Or are there any things that don't?

SCHROCK: I guess people would define what constitutes success differently. Most people think in terms of success, well, you make a real difference in the world. You win a Nobel Prize. You change the way chemistry is done. And that's obviously one way to describe success.

Or even financially, very, very successful, you've started many companies, and you're very wealthy. And you can become a philanthropist, you have so much money. And so that's another way, or a combination of those.

But there are lots of people who wouldn't probably define success as either one of those. Just educating students, watching them go on to successful careers, and you've guided them into successful careers, either in academics or in industry. They don't have to win Nobel Prizes to be successful, because those are rather rare occurrences.

So it depends how you define success. But I think in my terms, I would say guiding people into successful careers and doing the best I can with my career, however way it twists and turns. It twists and turns pretty well recently. So I've been very happy, and nothing to complain about. Absolutely nothing.

INTERVIEWER: Talk to me a little bit about teaching. Have you taught your entire time here at MIT, and do you like teaching?