Sect. Bruce Babbitt, "Preventive Measures Against the Threat of Marine Bioinvasions” - First National Congress on Marine Bioinvasions

[ELECTRONIC CHIME MUSIC]

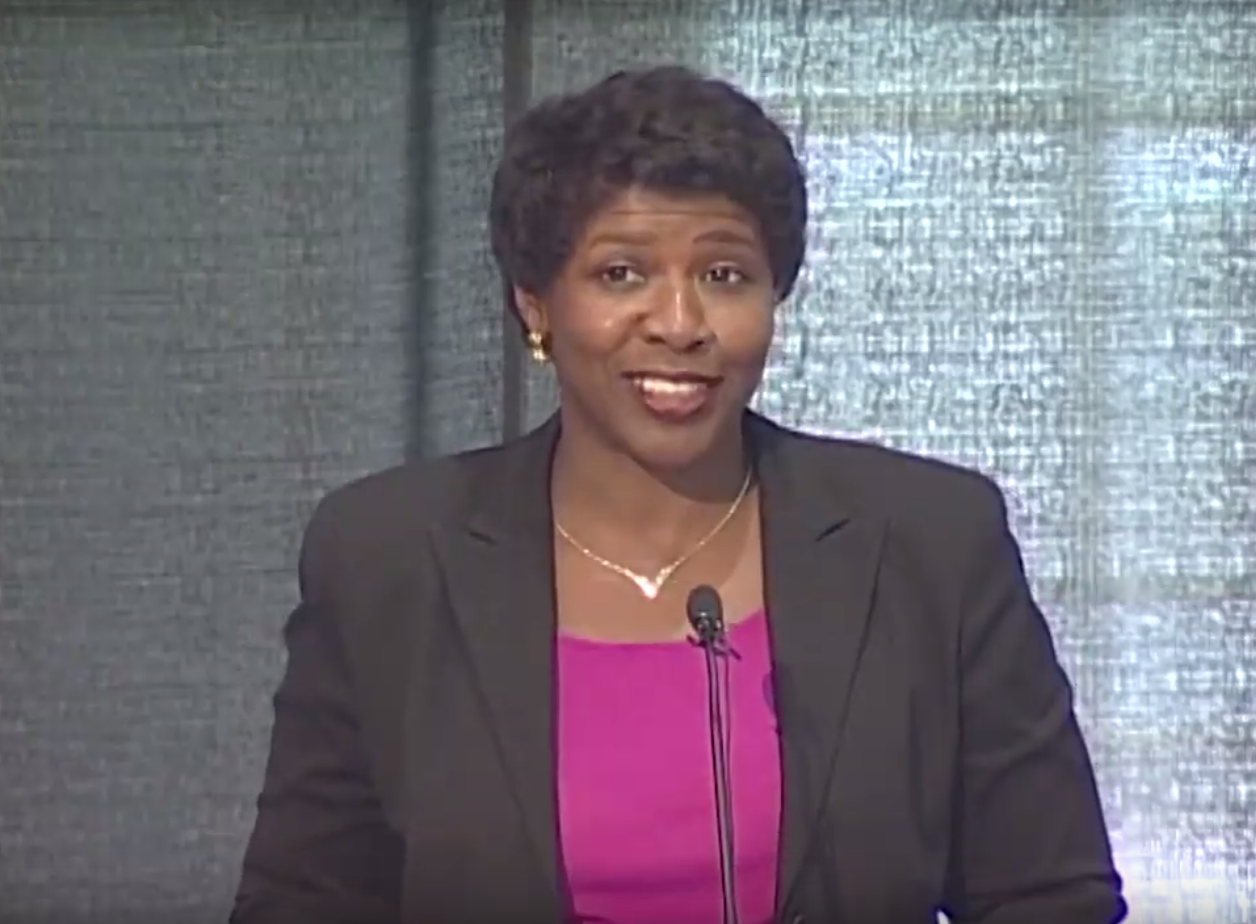

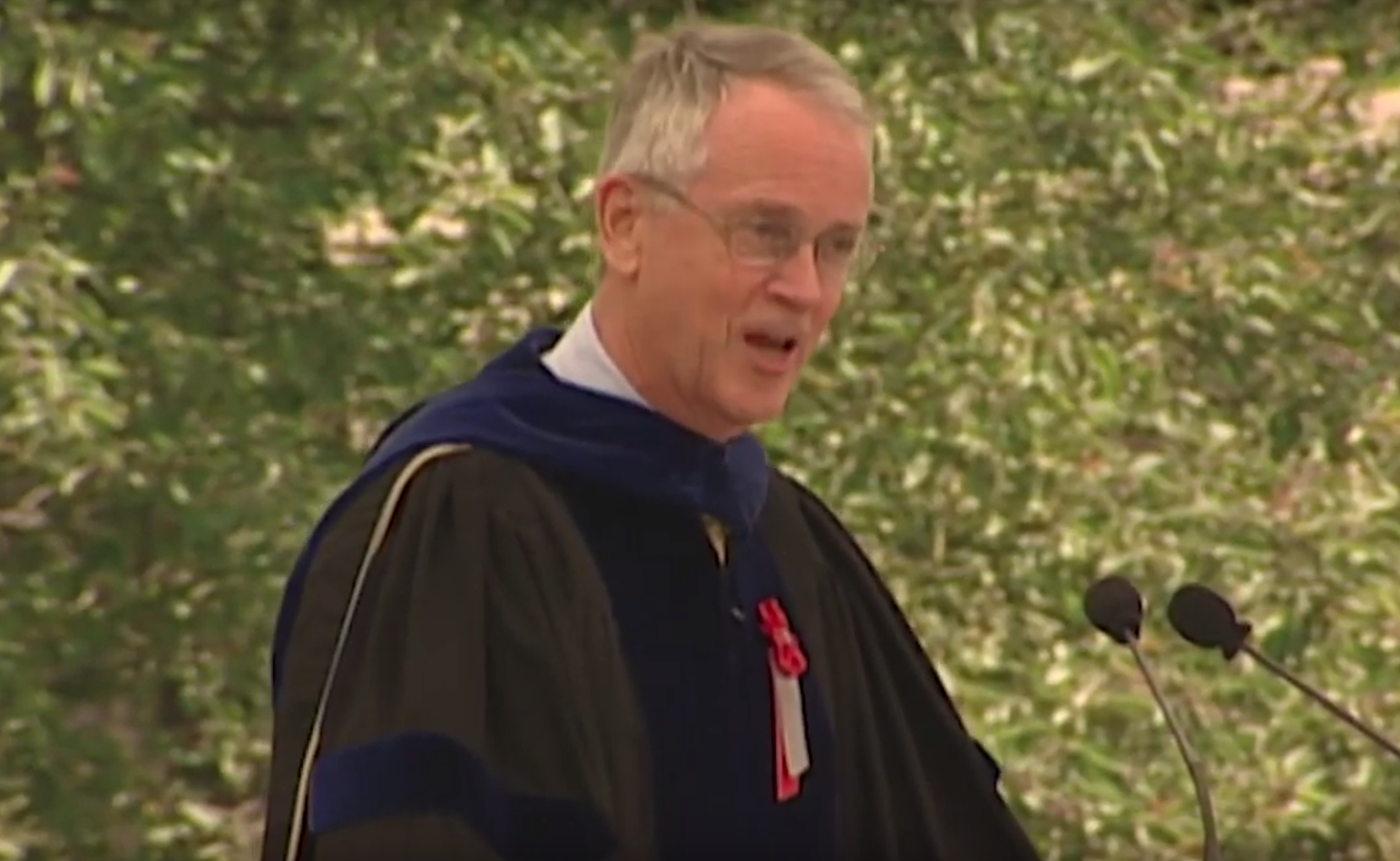

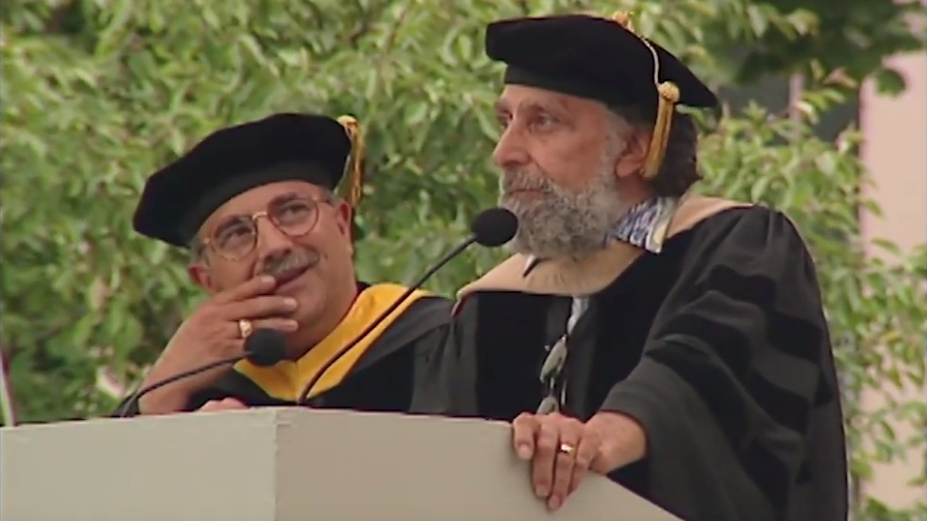

CHRYSSOSTOMIDIS: I'd like to very briefly tell you a little bit about Secretary Babbitt's academic background. He holds a degree, a Bachelor of Arts, in geology from Notre Dame. And he also holds a master's degree from Newcastle upon Tyne in England, which is quite fascinating, since I'm also a holder of the same-- I mean, not quite the same degree. I have a degree in naval architecture from the same university. And we must have crossed each other's paths in Newcastle, since we were even in the same building. So we even suffered together spotted dick and whatever else the British cuisine has to offer.

[LAUGHTER]

So. After that, he went to the other university. I forget. I think it's upstream. I think it's Harvard-- yeah, I'm sorry-- where he has received the LLB from the Harvard Law School. Secretary Babbitt is in charge of a department that is responsible for safeguarding our environment, a very, very important job for all of us. He has a unique style of management. He promotes consensus-based environmental restoration projects, which he gets a buy-in from a large number of constituents.

And then, as a result of this unique style of management, he has been highly successful in a number of areas. These include Florida Project, Pacific Northwest in California, and a number of others which I don't think I really need to spend a lot of time today. So I'll give Secretary Babbitt plenty of time to speak. But today what I like, he has graciously agreed to speak to us on the subject of our conference on marine bioinvasions and to share with us his plans for his department for ushering us into the next millennium for a safe and sound environment for all of us to live in. So Secretary.

[APPLAUSE]

BABBITT: Thank you, Chrys. Chrys, thank you very much. I'm really, frankly, surprised that you don't remember me from our student days at King's College at the University of Newcastle. Actually, there's an interesting story there. Because as Chrys suggested, I did study science as an undergraduate. And I received a Marshall Scholarship, which took me to Great Britain and the University of Newcastle.

And I had the great good fortune to arrive there at the very beginning of the plate tectonic revolution in a really extraordinary research group that was elaborating the geomagnetic aspect of all of this revolution that was taking place. Well, it was really quite exciting.

But after a year and a half with my classmate here and other truly talented physicists and chemists and engineers, I was walking home one night after an especially frustrating 12 hours in the lab. Everything-- well, you all know what that's about. Nothing seems to work, and nothing comes together. And on my way home, I was reflecting. And I said, I think I've discovered what the problem is. I'm not smart enough to be a scientist.

[LAUGHTER]

And I continued to reflect. And I asked myself, do I still have time to get into a softer line of work?

[LAUGHTER]

Well, there's still an opportunity. I thought, I've got to downscale my ambitions. And that took me to Harvard Law School.

[LAUGHTER]

From whence I degenerated into law and then politics. What am I doing here today? Yeah, that's a good question. My scheduling staff saw this invitation from Chrys, which said "bioinvasive exotic marine invaders." And so we can go right past that one. Nobody's interested. Besides, it's a topic for NOAA And it's in Boston. I mean, why could you possibly be interested?

I snapped it up, because I believe you are on to something of extraordinary importance here, and the effort that the sponsors of this conference have made and that you have demonstrated by coming together mark this event as an important beginning. And I think that many of you, in your respective fields, are going to look back upon this as saying you were present at the creation-- at the creation of a genuine response to what is now being recognized as a large and pervasive phenomenon that, of necessity, must bring scientists, policymakers, and the public together.

It's interesting that we come here on the 10th anniversary of the Exxon Valdez. And you, of course, remember the attention that that captured when this stone-sober captain crashed his tanker on a reef in Prince William Sound, whereupon some 10 or 11 million gallons of oil spilled, gradually slicked across the shoreline and the sound, and alerted-- awakened-- the American people to the problem of oil spills, as they saw birds, wildlife, coated with all this gunk, struggling for survival.

And in fact, that incident galvanized some very important response. Congress legislated a double hull tanker standard. There was a massive commitment to research, to remediation, mitigation, and a really worldwide attention to dealing with the regulatory aspects of oil tankers.

The one thing that didn't come out of that was attention to something else that was happening in Prince William Sound. A couple of years ago, the Fish and Wildlife Service showed up and said, "We've discovered four new species of zooplankton loose and spreading in Prince William Sound." And of course, it was very tempting to say that sober captain of the Exxon Valdez is responsible. But it's clearly oil tankers are responsible, if not that specific one, because it's a classic ballast water problem.

And I relate that to point up the difference in response, because those species of zooplankton out there in Prince William Sound may, in the long run, prove to be infinitely more devastating than the oil spill itself, because there is some suggestion that those species may now insert themselves in the food web, from phytoplankton on up, that leads to the Dungeness crab and an important fishery.

And of course, these are facts that have gone largely unremarked and unnoticed, because we are dealing with a phenomenon that, unfortunately, is out of sight and out of mind. And it is going to be a major task to try to bring these issues to public understanding. They're certainly there. You can go from Prince William Sound down to the Pacific Northwest, where, I don't know, 30%, 40% of the species in some of those sounds are now exotic invaders.

Go to San Francisco Bay. Well, on the way, you'll go past Willapa Bay in Oregon, where they've got a really fascinating little, very specialized invader problem, not from somebody else's country, but from our own. From where? The Atlantic coast-- a Spartina outbreak in Willapa Bay, which is having enormous impacts on the shellfish industry. They're reminding us that these pathways are many and varied.

But let's go to San Francisco Bay. This place surely stands as a warning to what can happen. We're looking at some, I don't know, 200, 300 species there, fish species of every kind, mollusks. The trophic levels of that bay have been totally scrambled.

Now the reason that's important from my perspective is that we're embarked in California upon a multi-billion-dollar attempt to restore the ecosystem of the Sacramento, the San Joaquin, the Bay Delta in San Francisco Bay. We have spent several years and vast efforts at trying to reassemble the ecosystem, only to turn and look at San Francisco Bay and say, what about the migratory salmon, all of the chub species, the smelt, and all the others?

If we restore the whole system from the Sierra Nevada to the Oregon border to Mexico, is it all going to be undone by this bottleneck in San Francisco Bay? Well, we don't know. But people are awakening to it. It's no different in the Gulf of Mexico. There's a mussel there that is impacting all sorts of fisheries and shoreline ecosystems.

And then we head to Boston. We head up the Atlantic coast. Got to tell you, I didn't even know what a whelk was. But I'm learning fast. It's a snail. Wow. But this critter is now lurking in Chesapeake Bay. It's coming out of the old Confederacy straight into the heartland of the American Revolution. It's on its way up Chesapeake Bay. It'll surely, quite probably, be in your neighborhood to join all of the other species that have already altered the visual coastline of New England and begun to impact the fisheries here.

Obviously-- and I don't need to tell you this-- these issues have been around for a long time. The great Columbian exchange is only one of many examples. And ships have been toting this stuff around a lot more slowly in much lesser volume for a long time. And it has clearly, for a long time, been a worldwide phenomenon-- alien invaders and the decline of endangered species.

For those of you who are from New England, I would refer you for an anecdotal look at this to none other than Herman Melville. You all read Melville in your spare time? Well, not being a scientist any longer, I thought I'd turn to Moby Dick for some enlightenment on this and. And lo and behold, Melville has a chapter devoted to the whale.

And this was, of course, when the wooden whaling ships were crisscrossing the globe in bloody pursuit of the leviathan in a world in which it was assumed that the ocean commons was A, infinite and B, stable across time and space. And Melville actually pondered. He devoted a chapter to asking "whether leviathan can long endure so wide a chase and so remorseless a havoc, whether he must not at last be exterminated from the waters."

And interestingly, he looked at the Great Plains of the American West. And he saw the impending near-extinction of the buffalo. And he then turned back to the seas and the diminishing whale stocks. And he said no. It's impossible on the high seas, because, he said, "If worse comes to worse, whales will escape to the icy fortress of the polar regions, and thus become immortal in their species."

Now obviously, that's about an endangered species. But it's a parable that I think has a lot of power about the ocean commons and the concept of limits and temporal change and the cultural problem that we face in trying to persuade the American people and members of Congress that there can really be any significant problem with a commons so vast. Well, you know the answer to that.

Well, so what do we do? Well, we haven't done enough. We've done hardly anything. We have one rather limited model that I think is worth your attention, both in terms of the policies, the science, the economics, the international cooperation. And that is, of course, the Great Lakes.

Because this problem began in the Great Lakes with the construction of two canals-- the Wellington Canal around Niagara Falls and the Erie Canal, which sort of brought us around in another direction. The Great Lakes system had been effectively isolated, in an evolutionary sense, by Niagara Falls. And all of a sudden, that barrier was removed.

The first signal of trouble was, of course, the lamprey, which simply decimated the Great Lakes fisheries. And because of the economics of that fishery destruction, we took action. And we now have some 20, 30 years of accumulated science with respect to attempts to contain the lamprey. And we've, of course, learned a lesson that you all know. And that is that, in most places in this world and in most ecosystems, the idea of eradication is simply not within reach.

We are spending millions and millions of dollars each and every year on lamprey control involving lampricides, electrical barriers, attempts at sterilization, all sorts of very expensive, very complex issues. And what we've managed to do is knock the lamprey population back to the point where the fisheries have come up. But it is a continuing struggle.

And of course, the Great Lakes brings up the international component. This is a joint Canadian-American effort. Canada begins to slack, we go up there and raise hell with them. We begin to slack off our efforts, the Canadians are there to urge us on. Well, that went on for years. And then all of a sudden, the zebra mussel arrives with a vengeance. Really, much more devastating than the lamprey, in the sense that it's just sort of scrambling, again, the trophic levels of the lake, filtering everything in sight through that system.

The interesting thing about the zebra mussel is it actually provoked a Congressional response. And the reason, of course, was because it was real-- clogging up power plants, screwing up boat hulls, sort of impacting the fishing industry. And Congress responded. Was an adequate response, perhaps, as a beginning. But we, I think, have learned a lot of lessons about how inadequate that response is. The major initiative that came out of that, of course, was ballast water exchange.

We started off, as we always seem to do in this business, by saying, well, let's have a voluntary program. And I'm thinking, do any of you know a tanker captain anywhere on the seven seas who is going to say, well, I'd just like to voluntarily do this? There are a few sort of pointy-headed scientists and visionary bureaucrats who would like us to do it voluntarily.

The answer is, of course not. Of course not. This is about raw, competitive economics. It is real simple. Either everyone does it, or no one does it. And we have now crossed that divide in the Great Lakes system from voluntary to mandatory. And of course, along the way, we've learned lots of things.

You've got hull pollution problems. You've got the whole issue of ballast sediments that need to be addressed. We've learned that ballast water exchange is not a silver bullet, but that there's a long ways to go, and that, ultimately, we're going to have to find some kind of approach that is more comprehensive, whether it's ultraviolet filtration, you name it. And we have not devoted the effort. But in the meantime, ballast water exchange is an important and necessary initiative which must now be extended to the entire American coastline.

Now We'll hear a lot of squawking, a lot of squawking. And we'll hear the usual things. It's not a complete solution. It won't prevent 100%. It will be expensive. How can we retrofit? How long can we get naval architects like Chrys into the action for a new generation in ships?

Well, we've heard all of this before. We heard it in the wake of Exxon Valdez, all of the same arguments. And we have now, quite successfully, moved toward a new set of oil tanker standards that are being implemented. And the lesson is loud and clear for ballast water exchange. We must travel the same path.

Now what specifically should we do? Well, I think, building on the 1990 Aquatic Invasive Nuisance Species Act, we need to step this effort up. Some of you, about a year ago, wrote a letter to the vice president highlighting this. And knowing your talent and clairvoyance, we were moved immediately to a response, which I believe is now going to result in the issuance of an executive order from the president very shortly, some time, I would say, within the next several weeks.

Obviously, the details of that remain for the president. But I think I can safely suggest to you some of the outlines of the directions that are likely to emerge from that executive order. And there are two of them that I would highlight. The first one will be that federal agencies take steps to use their existing authorities to prevent any further damage and to get control of these introduction problems, ballast water being one, but by no means the only one.

Executive orders have an interesting impact in the United States government. When I came here, I assumed that executive orders were just paper, because I'd go over to other agencies, and I'd talk about all these things, and the other response other agencies give me is, who are you to be over here poaching on our territory and preaching to us? We're doing just fine.

State Department always says to me, look, you're the Secretary of the Interior. You might be a little more modest about your responsibilities. Go back to buffalo and wolves. An executive order from the president saying get going will have, I think, a major impact.

Now the second thing we have to do that I believe will be prompted and moved by an executive order is put together a truly comprehensive plan at the governmental level. We've started this with the task force and the working group that came out of the 1990 legislation. But we've got to do a lot more. Obviously, I've talked about ballast water and the need for a nationwide regime which moves toward mandatory regulations for ballast water exchange.

Now some of you creative folks out here have said, well, what about using the Clean Water Act and the large regulatory clout of the Environmental Protection Agency to move in a straight line to that kind of response? Now see, once again, I'm over on somebody else's turf here. So I'm going to say this with deference to Ms. Browner and her very able regulators.

It's an idea that ought to be discussed. It has some obvious benefits and some obvious problems in terms of, it's one thing to prescribe regulations. It's something else to enforce them. And all of a sudden, you're into some very complex issues of the role of the Coast Guard, international treaties and regulations, a whole variety of issues. And it may be that the Congress will need to deal with this ballast water issue in a thoughtful and comprehensive way.

Your question may be, well, is the Congress capable of doing that?

[LAUGHTER]

Now or forever? Well, it's the only system we've got. So the answer is, we must.

Now there's another interesting set of issues here where I believe the agencies can, with your help and guidance, really make tremendous strides. And that is the use of customs, APHIS, fish and wildlife inspectors to deal with the stuff that is coming, not by tanker, but is coming through customs, the residue of a very intense global trading system, stuff that comes through and evades inspection in terms of aquarium species, the pathogens associated with raw fish products, all kinds of stuff.

Just by way of illustration, somebody did a study of-- this is not particularly a marine issue, but it's illustrative-- of a ship bringing Japanese timber into Oregon and found 363 species riding along on those raw logs from Siberia or wherever. And I suspect if we get into this, we're going to find that we've got a lot of hitchhikers, probably the same magnitude, slipping through in all kinds of different ways. And we simply have to step up our efforts.

Now Dan Simberloff has a very intriguing idea. He says our attitude toward, if you will, sort of customs screening from abroad has always been blacklisting species that have been proven harmful after the fact. Once the damage is done, then you put it on a blacklist. What I understand Simberloff to be saying is we should whitelist species and say nothing comes in until it has been demonstrated as much as reasonably possible to be, if not benign, at least not malevolent, OK?

We need to think and act on the research and development of control mechanisms, whether they are a chemical, fire, or bio controls, whatever it may be. And the problem with our research effort now is that, like so much of government, it's fragmented, and it tends to be directed at specific issues.

We need a crash project on melaleuca trees in the Florida Everglades. We go to Agriculture and say, search the world for the biocontrol. We get a leafy spurge problem out west. And all of a sudden, we're scouring the universe, looking for biocontrols. We tend to deal with it in a very fragmented kind of fashion. And somehow, we've got to look across our scientific establishment-- and that's in the Department of Agriculture, NOAA, the Department of Interior, universities, grant and aid programs, NSF, sea grant programs-- and see if we can't find an organizing principle.

Now the genius of scientific research in this country, and indeed, in many other countries, is that nobody's in charge of setting the agenda except individual centers, institutions, and scientists. Your freedom is the source of the creative genius of our system. But it also leads to anarchy. And there must be some way of imposing just the slightest amount of non-invasive, non-demanding sort of couldn't we all consider that the following things need systematic attention? And I believe that the president's budget request for the year 2000 is going to head in that direction with respect to the federal agencies.

Lastly, just a word about the international issues. You're aware that this is not a one-way problem. Anybody who has seen the damage that has been done to the Black Sea fisheries by our export of-- is it goby species?

AUDIENCE: Comb jelly.

BABBITT: Oh, it's the comb jelly. OK. The decimation of those fisheries is ample evidence that this is a modern Columbian exchange that goes in all directions and that, in fact, to have effective prevention controls, we've got to be working at both ends of the transportation pathway, where it starts and where it ends. And that's going to be a difficult, difficult endeavor. But we must get started.

There are a number of international biological treaties. And we have a World Trade Organization which will undoubtedly play a regulatory role. My own belief is that the Biodiversity Treaty is the correct way to handle this, that we need to acknowledge it head on as a pervasive biological issue and walk straight back to that treaty in section 8 and see if we can begin the process of acknowledging and negotiating the outlines of a protocol that will deal with this.

Now some of you out there, skeptical, may ask, well, that's absolutely fascinating, considering that the United States has never even ratified the Biological Diversity Treaty? Interesting problem. The treaty is enforced. There are regular conventions of the parties. And where are we?

Well, just as a mild suggestion, not meant to be disrespectful, perhaps we could prevail upon the United States Senate-- currently absent from all of these issues-- behind closed doors, dealing with those matters, to take on these issues and to get with the urgent necessity of ratifying that treaty and starting a vigorous and fruitful debate about how we find the tools to deal with these problems in a global context.

Well, I didn't mean to go on so long. But see, I get started, and I seldom have a captive audience for these kinds of things. And I very much appreciate the invitation. And in all seriousness, I would end where I started. And that is that your efforts together to raise the profile and deepen our understanding of these issues can and hopefully will be the beginning of a brand-new chapter in our recognition and attention to this problem. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

MODERATOR: I assume you will answer [INAUDIBLE]?

BABBITT: Sure, sure.

MODERATOR: Do we have some questions?

BABBITT: Yeah.

AUDIENCE: Secretary Babbitt, I'm Armand Kuris from the University of California at Santa Barbara. The news that the administration's executive order to prevent the entry of exotic marine species is extremely good news, as this will certainly greatly reduce the future problems. But what about the established pests, the introduced marine pests that are already here and are doing damage or have the potential to do considerable damage? Does the administration plan the development of a coherent policy, perhaps using tools such as subsidized fisheries, biological control, genetic manipulation in an integrated pest management approach to these problems?

BABBITT: The answer to the question is yes. Now a few thoughts. Obviously, there's an enormous amount of interest in biological controls. And we have a melancholy history that you all know about, with well-intentioned attempts to find the mongoose and bring it into Hawaii to take care of whatever it was-- the rats, I guess-- and rabbits in Australia for whatever purpose. And what we have learned over the last couple hundred years is that this is a very difficult issue, and it requires a lot of discipline and caution.

We are currently, as you well know, experimenting on land in the terrestrial systems with some pretty encouraging preliminary results. The Department of Agriculture is doing really systematic screening. And we have turned some critters loose on the melaleuca in Florida. We've got some now moving on the purple loosestrife front, some with leafy spurge out west.

And we've also been experimenting in the terrestrial systems with a variety of other issues of fire. It's interesting. Fire-like biocontrols can make matters worse. We've had a sort of unhappy experience with cheatgrass, which accelerates the natural fire cycle. It burns every year, and it destroys everything else. And it's an annual which co-evolved with domestic livestock in Europe and Asia. And those ecosystems historically had fire, but they didn't have cheatgrass. And now when they have fire and cheatgrass, we've got kind of an insoluble problem there.

I think the reason I'm going terrestrial is it's an implicit acknowledgment that we're not yet really onto these issues in coastal waters. But the answer is absolutely yes. We're not going to get rid of most of these things. We're going to have to find strategies of containment that minimize the damage and focus our research, do the best we can, admit we don't know everything, take an occasional risk, and hope for the best. Yeah, right here. If you just holler the question, if I like it, I'll repeat it. If not--

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE: Good morning, Mr. Secretary. I'm a project manager with the Regional Citizens' Advisory Council in Valdez. So your opening comments were of particular interest. One of the big gaps in the National Invasive Species Act was the elimination or the setting aside of coastwise trade as not participating in the voluntary ballast water exchange program.

And as you probably know, in Valdez, we get a lot of ballast from the US from ports that are themselves heavily invaded. And that is, obviously, of concern to us, because we want to protect the biointegrity of Prince William Sound. So the question, I guess, is simply a political one. Can we count on you for the support of changing that requirement when the National Invasive Species Act is up for Renewal

BABBITT: Well, I think the logic of dealing with this internationally applies equally to national transfers. I mean, the Spartina problem in Willapa Bay is from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Now I don't know whether that Spartina got there on a boat or whether it just sort of was in somebody's pocket or whether somebody did it deliberately. But that, to me, stands for the proposition that we must include this kind of analysis and controls.

I just read yesterday, the Atlantic salmon is now apparently loose in Puget Sound as a result of some aquaculture issues in British Columbia. And there's just absolutely no question that we have to see it in that and have the authority to do it. So the answer is yes. Way in the back.

AUDIENCE: I'm John Chapman from Oregon State University. And I think it's wonderful to ask you lots of things that you would do. And we appreciate that. But I wonder if you could give us some hints on how we could do a better job.

BABBITT: How can you do a better job? Well, look. You're the ones with the credibility on this problem. I got to tell you, there are a lot of places-- well, maybe a surprise to you-- but there are a considerable number of places in this country where if I say something, the tendency will want to-- the public response will be disbelief and a desire to do exactly the opposite.

[LAUGHTER]

In light of my credibility in the modern political system. You've got the credibility. And I think that imposes upon you, particularly in a complex, modern society, the imperative of advocacy. Now I don't think you need to cross the line into the political arena. What I mean by advocacy is finding appropriate and imaginative ways to highlight these issues and the economic consequences.

One thing that lies buried out there is the economic consequences of the problems that we already have. We are spending billions of dollars on containment issues and with a corresponding amount of lost revenues. I think there's a Cornell study out. I would encourage you all to look at that Cornell paper and ask, how can I translate this in my community? Because ultimately, the willingness of Congressmen and women to act is not a function of my speeches. It's a function of what they're hearing from their constituents. And you are their constituents. Right here.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. I'm Andy Cohen from the San Francisco Estuary Institute. You mentioned during your talks the issue of the whitelist versus the blacklist approach to regulating intentional introductions. In 1973, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, in fact, recommended a change to a whitelist approach. It was, in 1973, a politically untenable idea.

But there's a lot more concern about the issue this year. And there is, as you said, an impending presidential executive order. Can we expect that the Department of the Interior will show the boldness that the Fish and Wildlife Service did back in 1973 and recommend a change to a whitelist approach?

BABBITT: That question translated is, beneath all the rhetoric are you--

[LAUGHTER]

--Too wimpy to do what was promised 25 years ago? Well, I believe that some variant of that has to be done in some form, and that this interagency task force-- it will be given an 18-month mandate to prepare a comprehensive plan, legislation, regulation, budget, forgotten past promises. I'll still be there. And I haven't forgotten your question. OK. Let me take a couple more. This must be-- yeah. Claire, Claire, over here. Yeah, in the green vest.

MODERATOR: There's two over there.

BABBITT: Where? Yeah. Yeah, we're at 11:00. OK. This is the last one. It's 11 o'clock. And I think I've stayed out of trouble so far. So let's see what happens. It's usually the last one that bites you and provides the headline, which provokes a call from the president saying, "Bruce, what is it you were advocating up there?"

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE: With that lead in, Mr. Secretary, I might have to change my question.

[LAUGHTER]

Actually, I'm Rachel Jacobs from the Naval Surface Warfare Center out in Carderock.

BABBITT: Wow.

AUDIENCE: With the problem with ballast water, and in terms of what research we need to do, we've been told that we need to look into the problem. And yet, we've been given no guidelines on what exactly we need to do to compensate for ballast on Navy ships, which is as much of a problem on commercial ships as well.

And basically, I was wondering when the federal government-- your department and others-- would start giving us guidelines that we can actually go and create the technology to handle. There's always been a question whether or not the policy pushes the technology or whether the technology pushes the policy. And I'm wondering when Congress is going to say, what are the standards that we need to uphold?

BABBITT: Well, I would respectfully submit, now in my seventh year of dealing with the messy business of making policy in Washington, that you would be well advised to say to the admirals and whoever you work with, we can't possibly rely on having these folks up there hand some policy down from on high. We've got drive the policy-- we. Well, what is it? Naval Attack and Warfare?

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE: NSWC. Basically, Naval Surface Warfare Center.

BABBITT: OK.

AUDIENCE: We're right to the right to the west of you.

BABBITT: Fabulous. What you got to have--

[LAUGHTER]

What you got to do is design a battle plan.

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE: Well, then let me ask you another prong of the same question--

BABBITT: Wheel in the artillery and win.

AUDIENCE: We know that this--

BABBITT: Artillery is wrong. What do you call them? OK, no. Go on.

AUDIENCE: We know that the scientific community is working on the problem of invasive species of ballast water and other issues all pertaining to the same. However, there always seems to be a bit of a gap between what the scientific community does and then what we can convince Congress what they need to do and the extent of the problem. Is there any way to expedite the transfer of knowledge back and forth?

BABBITT: Well, I hope you will join our little task force that is going to be forthcoming as a result of the president's order. And we can get this thing stirred up. Now seriously, and then I'll quit. There's always a gap between the emerging science consensus around a problem and the natural reluctance of society to make large changes in the way we go about our economic life.

If you want a really large example of that, look at climate change. How frustrated do you think those scientists are? We have an absolutely rock-solid consensus on the reality of climate change. The factors which are driving that are simple enough to be understood by a high school student. And yet policymakers step back. That's a particularly egregious example. But it's part of the process.

And what it leads me to is saying, you've really got two alternatives. One is to send the elected representatives to school. Bring them to MIT. The other one is to say to the scientists, you've got to sort of step up across the gap into non-political advocacy, advocacy which is grounded upon your special expertise and the gifts which this society has allowed you to develop and repay us by stepping into the very risky public arena, cautiously but very firmly using your scientific weapons to accelerate the debate. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

Great. That was fun. That was a lot of fun. Thank you.