School of Humanities, Arts and Social Science (SHASS) 50th Anniversary Colloquium, “Asking the Right Questions” (Session 1) 10/6/2000

[MUSIC PLAYING]

COHEN: Hello. Hello. I'm Josh Cohen. I teach in the linguistics and philosophy department here. And I'm the head of the Political Science Department. And I'm up here now because I'm the chair of the Colloquium Committee that organized this two day event.

I'd like to welcome all of you to this first session of a two day colloquium entitled, Asking the Right Questions, in which we celebrate the 50th anniversary of MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. Since 1950, the school has been home to an extraordinary collection of scholarly activities, of composers and economists, linguists and literary critics, historians, anthropologists, philosophers, and many others, who pursue topics ranging from the analytical study of human language, market exchange and group conflict, to the interpretive examination of texts, histories, and cultures, to the imaginative exploration of human passions and relationships.

It's an unusual school and an unusual institution. And our hope is that you'll come away from these two days with a deeper sense of the contribution to knowledge that comes from the school. Not so much preoccupied with CP Snow about whether there are two cultures, or three cultures, or six, or nine, in the scholarly world, but instead engaged by the questions that we're going to be discussing here. Before proceeding, I want to express thanks to the other members of the committee that organized the event, Colleagues at MIT-- Pete Donaldson, Ross Williams, Alan Brody, and Olivier Blanchard.

But I particularly want to take the opportunity to thank Phil Khoury, who bears substantial responsibility for making this colloquium come off, bear substantial responsibility for everything that moves around this side of campus, and I think more fundamentally is really a person, as everyone who knows him knows, of extraordinary decency, a great pleasure to work with. And I'd like to thank him on behalf of everyone at MIT for all that he does for the institute.

[APPLAUSE]

All that he does at the institute, including, if I may say, until about 11 o'clock this morning sending me instructions about what I should be saying now. But I needed the instructions. I welcome it. So this two day colloquium is one of four parts of the 50th anniversary celebration.

A second part is an exhibition, which opened last month in MIT's Compton Gallery in building 10 called, A 50 Year Reflection on the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT. As I say, it opened last month. It's going to continue until the end of January. But it will be open this weekend, special hours. And the Nobel Prize medals will be on display.

But don't get any bright ideas. There's an MIT officer who's going to be guarding the medals. Another part of the four part event are some concerts tonight at Kresge, beginning at the Kresge oval at 7:15 with a performance directed by Evan Ziporyn. And then in Kresge auditorium at 8:00, a concert with performances by the MIT Wind Ensemble, the Chamber Music Society, Festival Jazz Ensemble, symphony orchestra, and concert choir.

And that concert will celebrate, among other things, the arts at MIT and the addition of the arts to our masthead, as in School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. And then the final event is the dinner tomorrow night at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Now, as to the colloquium itself, beginning about a year and a half ago, Phil Khoury organized a series of discussions about how we might celebrate our 50th anniversary.

And a consensus emerged through those discussions, that the right way to do this was not so much to applaud past efforts, or celebrate past achievements, but instead to have an event in which we do what we do when we do it well, that is to think, talk, and argue about large themes of real human importance. Time and world permitting, everyone in the school would have a chance to discuss his or her work. But Andrew Marvell was right, both time and world are in unhappily scarce supply.

So we decided to focus on four large themes that have been persistent foci of attention of humanists, artists, and social scientists over the 50 year life of the school. So we have four topics, each defined by a broad question. And I'll just state the questions, say who's going to be speaking to them, and leave to the panels themselves and the chairs of the panels the introduction of the themes in more detail and the introduction of the speaker.

So this session, what do we know about human nature? Will go from, well, 1:15 to 3:00, or so, with Noam Chomsky, Steve Pinker, and Hilary Putnam. Then, after a short break, at 3:30, we start again with a topic, how do artists tell their stories? With three artists who tell stories in different media, composer John Harbison, novelist Anita Desai, and poet Louise Gluck. Then tomorrow at 9:30, how do history and memory shape each other? With John Dower, Pauline Mair, and Dame Gillian Beer.

And we finish tomorrow at 1 o'clock with the question, is capitalism good for democracy? With Suzanne Berger, Bob Solow, and Ken Arrow. And I want to take this opportunity to thank all the participants on all the sessions, but particularly Hillary-- was my teacher in graduate school-- Gillian Beer, Ken Arrow, and Louise Gluck for joining us on this special occasion. All the sessions, as you probably know, will be in this room.

And as you may not know, for those who come tomorrow, lunch will be served in the faculty club between sessions. And on that mundane but essential detail, I'll hand things over to my friend Jay Keyser who is the Peter de Florez Professor of Linguistics, Emeritus. And Jay will introduce our first question. Jay. Thank you.

KEYSER: Welcome to the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences version of The Three Tenors. I will be your moderator for this session. You can tell who I am. I'm the one with the longest name on the name tags there. My name is Samuel Jay Keyser.

So I'll say a word about how the event will be structured and then we'll begin. So what I'll do is introduce each speaker. And they'll speak in the order of Steve Pinker and then Hilary Putnam and then Noam Chomsky. Each speaker will speak for about 20 minutes, and then we'll take questions from all of you.

And as Josh says, we should go up to about 3 o'clock. So I thought I might try to lay out a kind of a context for the discussion. In 1958, as a graduate student in linguistics at Yale, I was taught that the study of language was the study of finite corpora.

The job of the linguist was to choose a language, collect a finite, if large, corpus of that language and describe it. I remember that one of my old mentors, Bernard Bloch, used to refer to that exercise as collecting your 40 notebooks of Choctaw and then describing it. Three years later, I came to MIT. Here I learned something radically different.

"Language is a process of free creation, and I'm quoting, its laws and principles are fixed, but the manner in which the principles of generation are used is free and infinitely varied," end of quote. The quotation is from Noam Chomsky and the import is that language, an important, perhaps the most important aspect of human nature, is quintessentially infinite creativity within a finite set of boundaries. Now, this point of view often glimpsed in the 19th century by critics such as Wilhelm von Humboldt, or Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Friedrich von Schlegel, was elevated to the level of a science at MIT in the middle of this century.

Creativity, within fixed boundaries, goes beyond Homo sapiens. It is a reflection of a fundamental property of life. Unity, IE, fixed boundaries within diversity, IE, creativity, are two sides of the same coin. The 450 different species of birds that live on the shores of Lake Baringo in Kenya are, nonetheless, cut from the same cloth. The thousands of varieties of flowers are, in a sense, a single flower.

The faces of humankind, as varied as they seem to be, are, nonetheless, variations on a single face. The thousands of natural languages in the world are, at some level, the same language. From the perspective of unity and diversity, then nothing could be more natural than language. From the perspective of human nature, what is special is the element of freedom that accompanies our mental life as it is mirrored in language.

Well, that'll be sort of the context. And I'd like to go immediately to our first speaker, and that is Steve Pinker. By the way, I'm the emeritus Peter de Florez professor. Steve is the current holder of it. So in a way, I'm a surrogate father. Don't stay out late, Steve. It's a bit frightening to think that I've known Noam and Hilary longer than our first panelist has been alive.

I guess, that's the kind of thing you have to expect when you celebrate 50 years of anything. If careers where music compositions, Steve's would be the 1812 Overture with the fireworks reserved for his spectacular series of books aimed at the interested but uninformed general public. In 1994, The Language Instinct, his first book, was named 1 of the 11 best books of the year by The New York Times Book Review and it won the William James Book Prize of the American Psychological Association. In fact, he's the recipient of 2 William James Book Prizes, as well as the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Science and Technology.

He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction in the National Book Critics Award Circle-- Circle Award he should have won. Many have rested on the laurels of the likes of the language instinct, not Steve. He followed that book up with How The Mind Works in 1997, and Words and Rules in 1999, each a tour de force in its own right. And he's currently working on yet another to be called The Blank Slate. Steve is on a roll, one which I strongly suspect will go on for the next 50 years. Steve Pinker.

[APPLAUSE]

PINKER: Thanks, Jay. Thank you very much, Jay. Thank you, Josh. And thank you, Phil, and all of you for coming. The topic of this afternoon's symposium is, of course, of perennial importance, because everyone has a theory of human nature. Everyone has to predict how other people will react to their surroundings. And that means that we all depend on theories, explicit or implicit, on what makes people tick.

Much depends on our theory of human nature. It affects everything from how we manage our relationships and how we bring up our children, to our theories of education, politics, and law. For thousands of years, the dominant theory of human nature was the Judeo-Christian tradition, which had claims on the subject matter now covered by psychology and biology. For example, it proposed a modular theory of mind in which the mind contains a moral sense which can recognize standards of good and evil and uncaused decision making process and a capacity for love. The Judeo-Christian theory was based on specific events narrated in the Bible.

For example, the, we know that people have the capacity for choice because Adam and Eve were punished for eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge implying that they could have chosen otherwise. With the decline of literal interpretations of the truth of biblical events, the Judeo-Christian theory of human nature has been dissolving among intellectuals. But since a theory of human nature is necessary, a new one had to take its place. I'm going to suggest that the standard secular theory of human nature that's been with us until recently is composed of three doctrines, each associated with a modern philosopher. I should hasten to add that I'm going to be using these philosophers really as hooks for the ideas.

And it should go without saying that their actual bodies of thought are far more sophisticated than the sound bites that I'll present you today. The first is The Blank Slate, or tabula rasa, literally scraped tablet, often incorrectly attributed to John Locke. What he really said was as follows, let us suppose then the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas. How comes it to be furnished? When comes it by that vast store, which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety?

Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To that, I answer in one word, from experience. It's easy to see why The Blank Slate should have been an appealing doctrine in Locke's time, as it is today. Dogmas, such as the divine right of kings, are not self-evident truths, but have to be justified by experiences that minds can share. If ideas come from experience, then differences of opinion come from different experiences, not from defective minds. And therefore, at least in the conventional interpretation of Locke, it gives us grounds for tolerating differences of opinion.

If all of us are blank slates, this undermines the notion that the royalty and aristocracy have some innate advantage and suitability to rule, and conversely, it undermines slavery by saying that slaves are not innately inferior, or subservient. The Blank Slate has had an enormous impact on contemporary intellectual life. Psychology for much of this century has devoted itself to the study of the simple mechanisms of association that Locke first described. The social sciences have invoked culture and socialization as the primary explanatory constructs.

I'm going to give you an example of how the idea has penetrated into another famous 20th century philosopher. I think of a child's mind as a blank book. During the first years of its life, much will be written on the pages. The quality of that writing will affect his life profoundly. Who said that? Walt Disney. Now, the second doctrine was first introduced in the following verse by John Dryden in The Conquest of Granada.

I am as free as nature first made man, ere the base laws of servitude began, when wild in woods the noble savage ran. The expression the noble savages incorrectly attributed to Rousseau, although he did write something quite similar. So many authors have hastily concluded that man is naturally cruel and requires a regular system of police to be reclaimed, whereas nothing can be more gentle than him in his primitive state when placed by nature at an equal distance from the stupidity of brutes and the pernicious good sense of civilized man. The more we reflect on this state, the more convinced we shall be that it was the least subject of any two revolutions, the best for man, and that nothing could have drawn him out of it, but some fatal accident, which for the public good, should never have happened.

The example of the savages, most of whom have been found in this condition, seems to confirm that mankind was formed ever to remain in it, that this condition is the real youth of the world, and that all ulterior improvements have been so many steps in appearance towards the perfection of individuals, but, in fact, towards the decrepitness of the species. It's easy to see the appeal of the doctrine of The Noble Savage, that we are innately good and that our social institutions cause us to do wrong. There is no need for the domineering Leviathan, that Hobbes, Rousseau's foil in that passage, proposed. If we're nasty, our best hope is an uneasy truce, whereas if we're essentially noble, a happy society is our birthright, a cheerier thought.

Children, in a sense, are born savages. So if the savage in us is nasty, then child rearing is an arena of discipline and conflict, whereas if the savage is noble, child rearing consists of providing children with opportunities to develop their potential. Finally, it'd be nice to think that evil is the product of a corrupt society rather than a dark side that's insufficiently tamed. The Noble Savage, like The Blank Slate, has a remarkable degree of penetration in our unspoken theory of human nature. I think it can be seen in the respect for the natural and distrust of the man made that manifests itself in many arenas, such as the opposition to genetically modified food, the unfashioned ability of authoritarian styles of child rearing, and the understanding of social problems as repairable defects in our institutions, something that virtually all of us share, as opposed to an older view that they are part of the inherent tragedy of the human condition.

The third doctrine is commonly linked with Descartes, the notion of mind, body dualism. And again, I will give you a sound bite that doesn't do real justice to his body of thought. When I consider the mind, that is to say, myself in as much as I am only a thinking being, I cannot distinguish in myself any parts, but apprehend myself to be clearly one and entire. The faculties of willing, feeling, conceiving, et cetera, cannot be properly speaking said to be its parts, for it is one in the same mind, which employs itself in willing and in feeling and in understanding.

But it is quite otherwise with corporeal, or extended objects, for as there is not one of them imaginable by me, which my mind cannot easily divide into parts. This would be sufficient to teach me that the mind or soul of man is entirely different from the body. The Ghost in the Machine is the abusive term for this doctrine introduced by Gilbert Ryle 50 years ago. And it's easy to see why the notion that we are suffused with some non-mechanical spirit should be appealing.

Machines, such as the body is composed of, are insensate, built to be used and disposable. Humans are sentient, possessing of dignity and rights, and infinitely precious. Machines have some workaday purpose, like grinding corn, or sharpening pencils. Humans have a higher purpose, love, worship, good works, knowledge, beauty, and so on. Machines follow the laws of physics, behavior is freely chosen.

With choice comes optimism about our possibilities for the future and the ability to hold others accountable for their actions. Finally, given the doctrine of The Ghost in the Machine, the mind can survive the death of the body, an idea whose appeal should be all too obvious. Again, I think this is a doctrine that pervades our common sense theories of human nature. We see it in the fact that freedom, choice, dignity, responsibility, and rights are commonly seen as incompatible with a biological view of the mind. We see it in the common use of determinism and reductionism as boo words, as words that no one ever really explains what they mean by them, but everyone knows that they're bad.

And in everyday thinking and speech you often can see speculation about brain transplants. In reality, they would be body transplants, because as Dan Dennett pointed out, the brain transplant is the one transplant operation where it's better to be the donor than the recipient. And we see it in everyday language as when we refer to John's body, or even John's brain, which presupposes some entity that owns the brain, and yet is somehow distinct from it. I think over the last 50 years there have been a number of threats to each of these doctrines.

And in the rest of my remarks I'd like to indicate what they are and how we might deal with them. The foremost, I think, is the Chomskyan Revolution in linguistics and cognitive science, where Noam in the 1950s first proposed that, quite contrary to the doctrine of the blank slate, every normal child is fitted with a language faculty, a language acquisition device, which is necessary for the learning of languages to take place, no learning without innate learning algorithms. And in the rest of cognitive science, there have been parallel proposals for learning circuitry, which must be there in order for learning to happen. In developmental psychology, my colleague Elizabeth Spelke and others have shown that infants in the crib have a remarkable degree of cognitive and psychological faculties operating just about as soon as their brain has developed.

In behavioral genetics, the study of adoptees and twins, there is evidence that about half the variation in intellectual skills and in personality traits can be tied to differences in the genes. And evolutionary psychology has documented an astonishing list of traits that are universal across the world, 6,000 cultures, just as Noam has proposed a universal grammar, the anthropologist Donald Brown influenced by Chomsky has proposed a universal people, a set of traits that includes everything from logical operators in language to arranging of hair for aesthetic reasons to sexual and child rearing practices. And primatology has shown that our hairy cousins have a number of psychological abilities, such as a concept of number and many emotions and facial expressions, despite their lacking culture and socialization processes, as we see in people.

The Noble Savage, I think, has also been threatened. Behavioral genetics has shown that many of the nasty traits that we find in people, such as antagonism, a lack of conscience, a tendency towards violent crime, and psychopathy, are partly heritable. Neuroscience has identified brain mechanisms associated with aggression, as well as brain mechanisms that inhibit it. And evolutionary psychology and anthropology have documented that conflict is as universal in the human species as it is in the rest of the natural world.

This is my one graph of data. It shows the percentage of male deaths due to warfare in a variety of hunter gatherer and hunter horticultural societies indicated in red, mostly in the Amazon and in the New Guinea highlands. For comparison, the blue bar at the bottom shows the same statistic percentage of male deaths due to warfare in the US and Europe in the 20th century, including the statistics of the two world wars. So much for Rousseau. And I think The Ghost in the Machine has also come under threat.

Cognitive science is based on the computational theory of mind, a theory, I think, first most clearly articulated by Hilary Putnam in a famous 1960 paper. Although Hilary is now one of the severest critics of that original approach. Nonetheless, I think it's still the dominant approach in cognitive science and it tries to explain the airy immaterial processes of thinking and feeling in terms of the mechanical notion of computation, that beliefs are a kind of information, thinking is a kind of computation, and the emotions are a kind of feedback and control mechanism.

In neuroscience, also the ghost has been under assault, Francis Crick wrote a book called The Astonishing Hypothesis, alluding to the discovery that all aspects of thinking, feeling, and perception, as far as we can tell, can be linked to the physiological activity of tissue of the tissues of the brain. Now, these threats to the three secular doctrines have not been met with equanimity, and there have been hostile reactions to these developments of the last 50 years from both the left and the right. From the academic left, there have been accusations of racism, sexism, and Nazism of people, who are clearly none of those, for espousing refutations of the three doctrines.

Just as one nostalgic example, here's a poster from the mid 1980s coming here Edward L. Wilson, sociobiologist, and the prophet of right wing patriarchy. And if you see, the bottom of the slide says, bring noisemakers. Nice touch. The religious and cultural right have been just as outraged with accusations of immorality and spiritual bankruptcy. Here's a quote from the Weekly Standard, which I think is typical of the right wing press' reaction to the new sciences of human nature.

But evolution, cognitive science, and neuroscience are sure to give you the creeps, because whether a behavior is moral, whether it signifies virtue, is a judgment that the new science and materialism in general cannot make. In contrast, the Judeo-Christian view says that human beings are persons from the start endowed with a soul created by God and infinitely precious. This is the common understanding the new science means to undo. Why the fear and loathing? Why these intemperate reactions?

And how might they be addressed by people who are legitimately concerned with the human values they are taking to threaten? I think the fears can be reduced to three main ones. The first is the fear that if the mind has innate structure, then different races, sexes, or individuals could be biologically different. Blank is blank. If we're all blank slates, we are by definition identical. If something is written on the slate, different things could be written on different slates, and that would condone discrimination and oppression.

The responses to this are, first of all, that as the political scientist James Flynn wrote, the truth cannot be racist, or sexist, that regardless of what the facts turn out to be on average differences among subsets of people, for those who are interested in studying that sort of thing, that does not impact on the ethical and moral decision of how we ought to treat people. And in particular, discrimination against individuals on the basis of certain group averages, such as an entire race or sex is simply indefensible on moral and political grounds. A position, by the way, that I think was eloquently articulated by Noam Chomsky in a 1970 article called Psychology and Ideology.

Second fear is that if unpleasant traits are innate, aggression, xenophobia, sexism, race, rape, harassment, and so on, that would make them, first of all, natural, and therefore, good, or else be unchangeable. Their responses to this, that, first of all, the first part is a non-sequitur. Is does not imply ought, as the philosopher G. E. Moore pointed out 100 years ago, and conversely ought does not imply is. Even if it would be nice to think that people are basically noble savages, the niceness and pleasantness of that thought is not enough to make it true.

Also, the human mind is complex with many parts. And even if there were ignoble motives, it doesn't mean that we're condemned to ignoble behavior, because those motives are not the only contents of the mind. With a complex multi-part mind, ignoble motives can be counteracted by other motives and thoughts, such as an innate moral sense, or a cognitive recognition of the mutual benefits that come about through cooperation.

And indeed, only by understanding our darker side can we hope to control it by trying to pit the more noble motives against the ignoble ones. Finally, there's the fear that if behavior is caused by a person's biology, he can't be held responsible for it. As in, the excuse, I can't help it, honey. I'm just following an imperative to spread my genes. I think the response for that is, first of all, an ancient one, that explanation is not the same as exculpation, or as the saying goes, to understand is not to forgive.

It can't be true that when we understand what makes people tick, that we can no longer set up contingencies of moral evaluation, of reward, and praise, and condemnation that would, in the future, affect that kind of behavior. Also, bogus defenses for bad behavior are, in the 20th century, ironically, more likely to be cultural than biological. We've had the abuse expuse that was used to exonerate the Menendez brothers in their first trial, the pornography made me do it defense used by clever lawyers of rapists and harassers, and the black rage syndrome that William Kunstler was prepared to use to defend Colin Ferguson, the Long Island Railroad gunman.

But my favorite example is the song by the Jets in West Side Story that I'm sure you all remember. According to the Sondheim lyrics, the Jets sang, dear, kindly, Sergeant Krupke, you gotta understand, it's just our bringing up-ke that gets us out of hand. Our mothers all are junkies, our fathers all are drunks. Golly Moses, natcherly we're punks. So in conclusion, I think the religious theory of human nature was replaced within 100 years ago and more by the doctrines of The Blank Slate, The Noble Savage, and The Ghost in the Machine.

This theory is being challenged by the cognitive revolution and the revolutions in neuroscience, genetics, and evolution. It's seen as a threat to deeply held values. But I would argue that that threat is more apparent than real. On the contrary, I think the taking human nature into account can help us clarify these values. Specifically, it's a bad idea to say that discrimination is wrong just because the traits of all humans are identical.

It's a bad idea to say that war, violence, rape, and greed are wrong because humans are not naturally inclined to them. And it's a bad idea to say that people are responsible for their actions just because the causes of those actions are mysterious. They're bad ideas because they imply, either that scholars must be prepared to fudge their data for a higher moral purpose, or we must all be prepared to relinquish our values. And I would argue that that is one choice that I hope we don't have to make. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

Thanks.

KEYSER: That was great, Steve.

PINKER: Thanks, Jay.

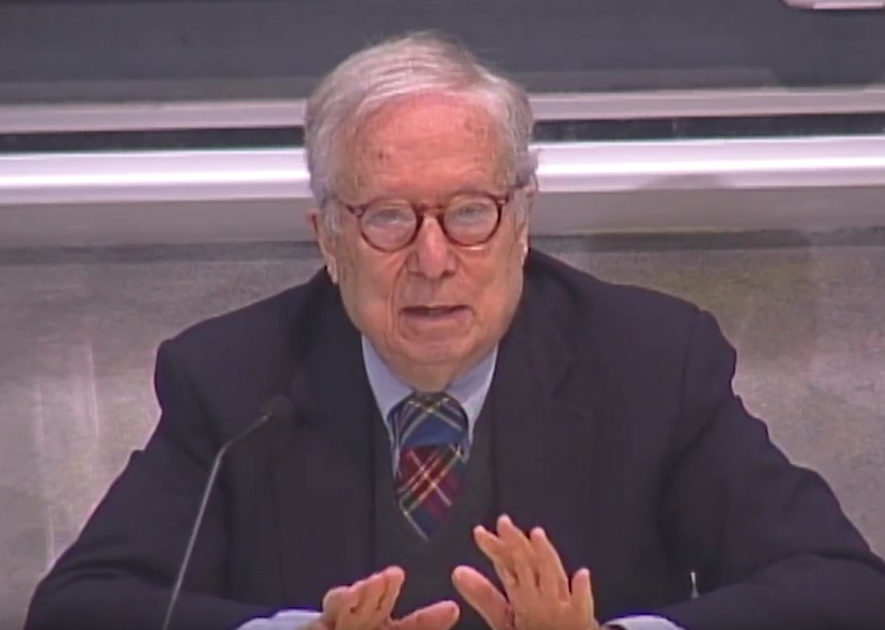

KEYSER: Our next speaker is Hilary Putnam. I first met Hilary when I came to MIT in 1961. It was his first of five years on the MIT faculty before moving on to Harvard, where he's been ever since. In a review of Hilary's recent book, The Threefold Cord, Mind, Body, and World, his fellow philosopher Simon Blackburn says, quote, "Hilary Putnam is one of the most distinguished living philosophers whose brilliant and fertile writings now span half a century. His range is enormous. It is difficult to think of an aspect of philosophy that he has not touched, from formal logic to the philosophy of religion, from quantum theory to ethics.

He has been constantly at the center of debates in the philosophy of mind and language, where positions that he was the first to articulate have become landmarks in the field." End quote. A colleague of mine recently told me that when the list of great philosophers of the last 50 years is compiled, Hilary Putnam will be among them. We are fortunate to have him here to help us celebrate 50 years of humanities at MIT. Hilary Putnam.

[APPLAUSE]

PUTNAM: I'm going to put these here. Compared to Steve Pinker, my range tonight will not be enormous. In the Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the article titled Godel's Theorem begins with a terse statement. Why is it doing that? This is a disaster. Any idea?

Something about the slide. I don't know. Well, this unreadable-- this opaque transparency. I think the lady who made it didn't know how to make them. Begins with a following terse statement. Those of you who knew him may-- in the interest know it was written by Jonathan [? Huyenard. ?] By Godel's Theorem, the following statement is generally meant, in any formal system adequate for number theory-- no-- we just had it.

Well, it's a dark subject. In any formal system-- and this is the first time I haven't made my own transparencies. From now on I go back to making my own. There exists an undesirable formula. There is a formula that is not provable, and whose negation is not provable. This statement is occasionally referred to as Godel's first theorem.

A corollary to the theorem is that the consistency of a formal system adequate for number theory cannot be proved within the system. Sometime it is this corollary that is referred to as Godel's theorem. It is also referred to as Godel's second theorem. These statements are somewhat vaguely formulated generalizations of results published in 1931 by Kurt Godel then in Vienna.

In spite of the forbidding technicality of Godel's original paper, the Godel theorem has never stopped generating enormous interest. Much of that interest is aroused by the fact that with the proof of the Godel theorem, the human mind succeeded in proving that there was something it could not prove, or at least not in any fixed consistent system with any fixed finite set of axioms and with the usual logic as the instrument with which deductions are to be made from those axioms. In fact, the theorem is much stronger than this. Even if we allow the system in question to contain an infinite list of axioms and to have an infinite list of additional rules of inference, the theorem still applies.

Provided, the two lists can be generated by a computer, which is allowed to go on running forever. Moreover, instead of speaking a formal systems adequate for number theory, or adequate for at least number theory, one can speak of computers. Such version was first stated by Alan Turing. The theorem says that if a computer is allowed to write down formulas of number theory forever, subject to the constraints that, one, any deductive consequence of finite be many of the formulas in the list that it writes down will also get written down in the list sooner or later, and, two, the list is not inconsistent, that is it doesn't contain some formula and the negation of that same formula, then there is a formula, in fact, the formula that says that the list is consistent is an example, that is not included in the list of formulas generated by the computer.

If we speak of the formulas listed by the computer as proved by the computer, and of a computer of the kind just mentioned as a consistent computer, we can say this succinctly as follows. Yeah, this will be another one. No, no. This is the wrong-- oh, I guess I did-- did I? Oh, yes, it was at the bottom of the page. Yes, the bottom of the same page. That's right.

There is a procedure by which, given any consistent computer, a human mathematician can write down a formula of number theory that the computer cannot prove. Of course, those who draw remarkable conclusions from this don't mention you could also say there's a procedure by which, given any consistent computer, a computer can write down a formula of number theory that the computer cannot prove. In 1961, the Oxford philosopher John Lucas claimed that the Godel's theorem shows that non-computational processes, processes that cannot in principle be carried out by a digital computer, even if its memory space is unlimited, go on in our minds.

He concluded that our minds cannot be identical with our brains, or with any material system, since assuming standard physics, the latter cannot carry out non-computational processes. Actually, that's not actually known, by the way, but I won't jump up and down on that. And hence, that our minds are immaterial. More recently, Roger Penrose used a similar but more elaborate argument to claim that we need to make fundamental changes in the way we view both the mind and the physical world.

Penrose, too, claims that the Godel's theorem shows that non-computational processes must go on in the human mind. But instead of positing an immaterial soul for them to go on in, he concludes that these non-computational processes must be physical processes. Physical processes in the brain, and our physics must change to account for them. I was early called upon to review Penrose's argument.

And my review was later republished in the American Math Society. And like the others who studied it, I found many unfillable gaps. But relax, I'm not going to ask you to listen to the details of Penrose's argument, nor to a listing of the places at which it goes wrong. That's something you can find in the literature, if you are interested. The fact is that Penrose himself seems to recognize that there are gaps in his argument, even though at the beginning he promises, I quote, "clear and simple proof," unquotes.

And in the end, he offers a series of arguments, which are not mathematical at all but philosophical. The philosophical arguments that Penrose throws in to plug the gap in his mathematical reasoning are numerous. And they're not sharply set out, but the heart of his reasoning seems to go as follows. Let us suppose that the brain of an ideally competent mathematician can be represented by a consistent computer, or a consistent computer program, a program which generates all and only correct and convincing proofs. The statement that the program is consistent is not one that the program generates by Godel's theorem.

So if an ideal human mathematician could prove that statement, we would have a contradiction. This part of Penrose's reasoning is uncontroversial correct. It is possible, however, that the program-- remember, this program is supposed to reproduce the competence of an ideal human mathematician. It's possible, however, that this supposed program is too long to be consciously apprehended at all, as long as the Boston telephone book, or even orders of magnitude longer. In that case, Penrose asks, how could evolution have produced such a program?

It would have to have evolved in parts and there would be no evolutionary advantage to the parts. But the objection that it's hard to see how such a thing could evolve in parts is a standard objection to all, or just about all evolutionary explanations. One, that it has proved possible to overcome in case after case, so though the details cannot, of course, be predicted in advance. First of all, evolution had better not endow intelligent beings who are to have any chance of survival with reasoning patterns that lead to contradictions in daily practice.

If we were always falling into contradiction in our everyday reasoning, we would be so confused we would not be around long enough to pass on our genes. Of course, there are parts of mathematics in which contradictions have arisen. For example, in Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers. It was at first possible to prove both that there was and that there was not a greatest transfinite ordinal.

What mathematicians did was to add to Cantor's theory certain, more or less, ad hoc restrictions, such as Russell's theory of types to get rid of the paradox, or to get rid of it as far as we know. In short, everyday mathematical reasoning is consistent. It wouldn't have arisen if it wasn't. And when [? Rishashay ?] mathematics turns out to contain contradictions, we simply troubleshoot it. In fact, even before Cantor, we had to troubleshoot the definitions of continuity, limits, et cetera, in the calculus.

The consistency of mathematics to the extent that it is consistent is not such a miracle. I think I know Penrose's response to this argument. In fact, he has a website in which he gives responses to my criticisms and those of others. He will say I believe that evolution might explain why we evolved a program which is consistent, at least in its elementary parts, such as the theory of whole numbers, but that we evolved a style of reasoning, which is correct, that is which corresponds to the platonic truth about the numbers, would be a miracle.

The alternative, he suggests, is that instead of a huge program, which miraculously corresponds to the platonic truth about the numbers, we have something quite different, a purely physical capacity to perform non-recursive operations in our brains. Of course, this argument of Penrose is one to appeal only to those who are willing to accept his odd combination of views, a Platonist view of mathematics, and a purely materialist view of the brain. What his argument ignores is the fact that the correct interpretation of our mathematical concepts depends on the use we make of them.

Evolution might indeed have programmed us with a different formal system, but to imagine that we had been endowed by evolution with a radically different system is the same as imagining that we had been endowed with a disposition to develop different concepts. It's not as if the meanings of our words were fixed prior to what we do with them, and evolution had the task of endowing us with a program for using words with those antecedently-fixed meanings. Evolution just has to enable us, it just has to give us a program which will enable us to succeed in our lives.

If we do, then our mathematical concepts will admit of some interpretation, under which what we say is right. In fact, that follows from another theorem of Godel, the so-called Godel's completeness theorem. To see what we can learn about the human mind, or at least about how we should or rather shouldn't think about the human mind from the Godel theorem, I need to point out two objections that must be raised against the very question that Penrose asks, the question whether the set of theorems that an ideal mathematician can prove could be generated by a computer.

I don't have a slide to go with this. The first objection, and this is a point I want to emphasize, is that the notion of simulating the performance of a mathematician is highly unclear, or perhaps, I should say, highly ambiguous. Perhaps, the question whether it's possible to build a machine that behaves as a typical human mathematician behaves is a meaningful empirical question. Say, can you build a machine which passes a Turing test for being a mathematician?

But a typical human mathematician makes mistakes. The output of an actual mathematician contains inconsistencies, especially if we are to imagine that she goes on proving theorems forever, as the application of the Godel theorem requires. So the question of proving the whole of this output is consistent does not even arise. To this, Penrose replies in the Shadows of the Mind, his book Shadows of the Mind, that the mathematician may make errors, but she corrects them upon reflection.

This is true, but to simulate mathematicians who sometimes change their minds about what they've proved, we would need a program, which is also allowed to change its mind. There are such programs, but Godel's theorem does not apply to them. Trial and error machines, they are called. The second objection is that to confuse these questions, the question of what an actual mathematician can do, and the question of what an ideal mathematician who lives forever can do, is to miss the normativity, the value laden character of the notion of ideal mathematics. The description of normatively ideal practice in mathematics, or any other area, is not a problem for physics.

It's not my aim to criticize those who make the mistake of thinking that the Godel theorem, or merely to criticize those who make the mistake of thinking that the Godel theorem proves that the human mind or brain can carry out non-computational processes, that Lucas and Penrose have made a serious blunder in their claims about what the Godel theorem, quote, "shows about the human mind," unquote, is after all widely recognized, at least in the logical community. At the same time, however, a view which may seem just at the opposite end of the philosophical spectrum from the Lucas, Penrose view seems to me to be vulnerable to the objections I just made. I refer to the widespread use of the argument in philosophy as well as in cognitive science that whenever human beings are able to recognize-- here I've put this slide--

I think she printed this out on a notebook insert, or something, instead of transparency paper. I refer to the-- why can't we see it at all. Well, maybe when I read it. I refer to the widespread use of the following principle in philosophy as well as in cognitive science, whenever human beings are able to recognize that a property applies to a sentence in a, quote, "potentially infinite," unquote, IE, a fantastically large set of cases, then there must be an algorithm in their brains that accounts for this, and the task of cognitive science must be to describe that algorithm.

The case of mathematics shows that that cannot be a universal truth. And my criticism of Penrose can enable us to see why we shouldn't draw any mystical conclusions about either the mind or the brain from the fact that it isn't a universal truth. But first, a terribly important qualification, especially given who my fellow symposiists are. And Noam and I were undergraduates in the program in linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania together as far back as 1944.

I have no doubt that human beings have the ability to employ recursions, another name for algorithms, both consciously and unconsciously, and that there are recognition out abilities that cognitive science should explain, and in many cases, does explain by appealing to the notion of an algorithm. The magnificent contribution of Noam Chomsky, in particular, shows our ability to recognize the property of grammaticality is explainable in this way. Why then do I say that the case of mathematics shows that it cannot be a universal truth, that whenever human beings are able to recognize that a property applies to a sentence in a potentially infinite, that is a fantastically large set of cases, there must be an algorithm in their brains that accounts for it?

Not quite ready for this. Well, just as it is true that we can recognize grammaticality in a fantastically large set of cases, it is true that we can recognize being proved in a fantastically large set of cases. And the Godel theorem does show, although, by the way, this requires a different argument from Penrose, that if there is an algorithm that accounts for this ability, we're not going to be able to verify that there is. That is the Godel theorem does not show that our cognitive competence cannot be totally represented by a program, but it does show, at least if you extend the argument, and include not just on deductive competence, but our inductive competence, that if there is a program that simulates our ideal rationality, then it would be beyond even our ideal rationality to recognize the program that does it is having that property.

But I think it would be wrong-- and this is a conclusion I point out in a paper called Reflexive Reflection some years ago. But I think it's wrong to just stop with that conclusion. It's wrong because talk about a potentially infinite set of cases only makes sense when there's an algorithm that we can verify. Why do I say this? Well, think for a minute about the mathematician that Penrose imagines he is talking about. If the mathematician could really recognize the potential infinity of theorems, then she would be able to recognize theorems of arbitrary finite lengths.

That's what it means to be able to recognize a potential infinity of theorems. For example, theorems to be too long to be written down before all the stars are cooled down, or sucked into black holes, or whatever. But any adequate physics of the human brain, even the one proposed by Penrose, if it turns out to be right, will certainly entail that the brain will disintegrate long before it gets through trying to prove any such theorem. In real actual fact, the set of theorems, a physically possible human mathematician can prove is finite.

Moreover, it's not really a set. This is why I think my little theorem about the unrecognized ability of any algorithm that totally reproduced ideal human competence, so it doesn't engage the real issues, because it grants that there is such a thing as the set. I don't think there's-- it's not a set, because sets, by definition, are too valued, an item's either in or out. But the predicate prove is vague.

We can, of course, make it precise by specifying a fixed list of axioms and rules to be used. And that was why, in fact, axiomatic mathematics was developed in the 19th century, to make the notion of a proof more precise, but at a cost. The Godel theorem shows that when you make the notion of approved precise in that way by fixing the axioms and rules to be used, then there's a perfectly natural sense in which we can prove a statement which is not drivable from those axioms by those rules. In other words, you didn't capture the whole of the notion of informal mathematical proof.

Now, you might be driven to say, OK, by proof, I mean, or by prove, we mean prove by any means we can see to be correct. But this uses the essentially vague notion, see to be correct. In short, there isn't a potentially infinite set of theorems a mathematician can prove concerning which we can ask, is it recursive, or non-recursive? What there is a vague finite collection of theorems that a real flesh and blood mathematician can prove. And vague finite collections are neither recursive nor non-recursive. Those concepts only apply to well-defined sets.

Awful. But it may be objected. Didn't Chomsky teach us that we can and should idealize language users by imagining that, like ideal computers, they can go on generating grammatical sentences forever, sentences of arbitrary length? Yes, he did. But the idealization he showed us how to make is only precise because it corresponds to a well-defined algorithm. If we take the question, what can an ideal mathematician prove to be a precise one? We must specify just how the mathematicians all too finite brain is to be idealized, just as Chomsky did.

And if we do it by specifying an algorithm, then, of course, the result will be computational. If this is right, then we should not allow ourselves to say, the set of statements that a mathematician can prove is a potentially infinite set. We should only say that there are fantastically many statements a mathematician, an actual mathematician can prove, at least in this informal sense, and let it go with that. It does not follow from that fact that there's an algorithm such that everything an ideally competent mathematician would, or should one say, should? Count as proving a mathematical statement, is an instance of that algorithm.

Let's see. Do I have one more? Maybe so. Yeah, I guess that's it. Yeah, I don't have. It doesn't follow. As I say, that there is an algorithm such that everything an ideally competent mathematician would count, or should, count as proving a mathematical statement is an instance of that algorithm, any more than it follows from the fact that there are fantastically many jokes that a person with a good sense of humor can see to be funny. That there's an algorithm, such that everything a person with an ideal sense of humor would see to be funny is an instance of that algorithm.

There is a moral here for all who are interested in cognitive science. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

KEYSER: When I came to MIT 39 years ago, I had been invited to join a project under the auspices of Morris Halle and Noam Chomsky. Morris was at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Palo Alto when I came. So Noam was the first person I met at MIT. I took him to be typical of the place, and so I thought I'd come.

At the time, there was what Tom Kuhn would have called a paradigm shift in linguistics. The scholars under whom I had studied did things one way and Noam did it another. The discussions were unusually heated and not without cause. If Noam was right, then much of the work being done in the field was not just wrong, which in science is no crime, but worse, it was useless.

I remember walking along Vassar Street with Noam to a coffee shop on Mass Avenue where the student center now sits. I regret that many people in this audience can't have that memory in their heads. It was a wonderful shopfront there and there was a coffee house, like the Balt in Princeton, and we used to go there and it was a great place. I think WBUR had radio station there. And it all changed when there was a fire.

Anyway, I was walking with Noam to that coffee shop, and I asked him what his opinion of the linguistic wars was. He said, graduate students have no vested interest. They will follow the most interesting questions. He was right, they did, and I was one of them. Later, Noam told me that, in his opinion, success in linguistics was not a question of talent, but rather of character, something which undoubtedly explains the differences in our two careers.

In 1974, I had the pleasure of introducing Noam at the Summer Institute of Linguistics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Since everyone knew who he was, I thought rather than read bits and pieces from his biography, I would read his horoscope. 25 years later, for the same reason, I have the pleasure of reading his horoscope again. Shake off lethargy, put aside preconceived notions, emphasize the new, be bold, in your presentation. Noam Chomsky.

[APPLAUSE]

CHOMSKY: Well, I won't try to react to that. I do, however, have one advantage over Hilary. I'm not going to have any problems with my transparencies, because I've managed to get through 50 years without having had any. And I have one advantage over Steve, and namely I'm not even going to try to answer the question that was posed, which makes life easier. Conclusions about human nature are likely to have large scale human consequences, and therefore, they have to be advanced with scrupulous care and with a recognition of how little is understood when we pass beyond fairly simple systems.

That's true elsewhere in the organic world as well. I don't feel that the question that's raised for discussion can be answered with much confidence in the areas that are of greatest concern and significance for humans, at least not by me. So I'm going to keep to a few words about the questions rather than the answers, and how they've been conceived, and the kinds of problems they raise when we do try to address them. Well, at a very general level, the question falls within a familiar pattern of inquiry in general biology.

We're interested in determining what's sometimes called the norms of reaction, that is the mapping of an environment into a phenotype, which corresponds to a genetic constitution, particular genetic constitution. I happen to be paraphrasing a well-known evolutionary biologist, but the point is familiar. And we can understand human nature to be the norms of reaction of the species abstracting away from variation, which is probably fair enough in the general study of humans since variability seems to be fairly small, certainly relative to our understanding, but even relative to closely related species.

The particularly informative in this quest is a phenomenon that's been called canalization by biologist C. H. Waddington some years ago. That's a process whereby the end state of development is relatively independent of environmental perturbations, so therefore, heavily constrained by the genetic endowment and particularly informative about it. These ideas are actually reminiscent, closely reminiscent, I think, of traditional rationalist conceptions of the origin and nature of mental faculties. These efforts, 17th, 18th century, also concentrated on what appeared to be fixed and highly structured outcomes that were thought to vary little with experience, probably incorrectly, called common notions since the early 17th century.

This whole perspective became influential in general human psychology in the 1950s, in part that was under the influence of ethology, comparative zoology. At first, there was a good deal of debate over the way the proposals were formulated. Konrad Lorenz, who was particularly influential, insisted that specific behaviors were innate, by which he meant that the actual behavioral outcome is genetically determined. And as was quickly pointed out, that no one expects-- no biological trade is expected to be a product of the genetic endowment alone, or trivially a product of the environment alone.

The outcome is expected to be some complicated interaction, interplay of genetic constitution, and the environment, of course, of the environment with developmental interactions and processes that remain rather poorly understood. To discover the genetic constitution, these various factors have to be disentangled somehow. And it's valuable to apply the approach, the traditional rationalist approach, the canalization approach, and to take a close look at possible ranges of outcomes.

The more highly structured and restricted they are, the more richly articulated and canalized, the more we're likely be able to find something out about the organism. Well, the logic of the situation dictates that the endowment that determines what the organism can become, the scope of possibilities also determines the limitations of development. So, for example, the same endowment that makes it possible for a certain embryo to become a mouse is going to prevent it from becoming a bird.

And we should expect the same to be true when we approach higher mental faculties across the board, in fact. So for example, it ought to be true when we consider the largely unknown capacities that enable humans to acquire deep understanding in certain domains of inquiry. And by the same token, prevent this in some other, least possible domains of inquiry, which might be actual, and which might even be important, and which might, for example, include the study of human nature.

The human nature raises questions that we may not have intelligence enough to answer. Descartes speculated, maybe rightly, and maybe it's not a matter of enough intelligence. Now we look at it differently, but the wrong kind of intelligence. Not an option for Descartes. Such an intrinsic structure of intelligence, which has to be there, should not occasion regret the-- throughout the biological world, the limitations that follow from the very same endowment that makes possible rich-- and states rich outcomes.

So it should be an occasion for celebration. But there are things we can't do, even if some of them turn out to be things we might like to do. Well, that's been the framework for the study of language for about the last half century. The norms of reaction, or sometimes called a language acquisition device, what Steve called the language instinct, the human genetic endowment, that determines a specific language given particular course of experience, and by the same token, prevents other language like systems from developing in the mind.

About these aspects of human nature, a fair amount is known, at least, more or less, understood, but I'm not going to talk about that. In principle, it ought to be possible to approach other higher mental faculties in the same way. In practice, the difficulties mount very quickly. Language appears to be relatively isolated from other cognitive capacities. I'm referring here to its structure, not its use, and not to components of the structure, which may be shared all over the place. When you turn to other aspects of mind, for example, or moral nature, it's much harder to isolate components for separate study, abstracting them from reflective thought and many other factors.

Now, nonetheless, the topics have been investigated in various ways. There have been illuminating thought experiments. There's been some experimental work with children. There's comparative studies of cross-cultural and even extending to other species. Not uncommonly, the real world offers occasions, instances, illustrations of how the faculties function. Often, these are painful choices. And probably, saw a couple of weeks ago that in England British judges and along with moral philosophers and the church and many others were agonizing over the question of whether it's legitimate to murder a child, one of two Siamese twins, in order that the other might have a chance to survive.

Questions like these test our moral faculties, a hard test in this case, maybe impossible one. And pursuing them may enable us to discover something about their nature. That's the kind of thought experiment that has been quite interestingly pursued. Sometimes this perspective, this generally ecological perspective, if you like, is counter-opposed to another one, it's called a relativistic one, which in an extreme form holds that, apart from the basic physical structure of a person, humans have no nature. They only have history.

Their thought and their behavior can be modified at will and without limit. Actually, nothing like that can be literally true, but such views are rather widely articulated in some form. In a version that's due to Richard Rorty, he whom I'm quoting now, "humans have extraordinary malleability. We are coming to think of ourselves as the flexible protean self-shaping animal, rather than as having specific instincts. Therefore, there can be no moral progress in human affairs. Just different ways of looking at things.

We should put aside the vain effort at exploration of our moral nature, or reasoned argument about it. We should keep, to what he calls, manipulating sentiment, if we happen to be for or against torture, or massacre, or whatever." I'm probably misinterpreting. I can't imagine that the words mean what they seem to say, but at least that's what they seem to me to say. These proposals have, maybe not surprisingly, evoked a good deal of criticism.

One recent paper in the philosophical foundations of human rights, discussing Rorty and others, suggest, and quoting again, "that nobody would have taken a Nazi seriously who had claimed in 1945 that the sole basis for moral condemnation of the Holocaust is just culturally relative emotional manipulation based on shrewdly devised sentimental stories." Well, if that's so, and I assume it is so, we want to know why. Why is that so? And if nobody, the word nobody includes all normal human beings, well, we're back to the question, the hard question of intrinsic human nature, back to the question, but not an answer.

This notion of unique human malleability, contrary to what Rorty suggests, is not at all novel. It's quite conventional. It goes at least back to the man, beasts, machine controversies that were inspired by Descartes. Here's one typical example, argument, in 1740 by James Harris, English philosopher, saying that, unlike animals and machines, the leading principle of man is multi-form, originally uninstructed, pliant, and docile. Weakness of instinct leads to vast variety, but also to extreme malleability.

That's an idea that has a long and quite inglorious history since that time. Well, with no metric, no way of measuring what how variable humans are as compared with others and with very little understanding, it's pretty hard to make any sense of such judgments. But whatever merit they have, they don't seem to seriously offer an alternative to the approach that I outlined before this roughly ethological approach. We can take for granted, it's undoubtedly true, that a person's understanding and judgment, and values, and goals reflect the acquired culture, norms, and conventions.

But how are these acquired? They are not acquired by taking a pill. They are constructed by the mind somehow on the basis of scattered experience, which they are constantly applied in circumstances that are novel and complicated. These are important facts. They were discussed about the same time as James Harris more than 250 years ago and by David Hume. He pointed out that the number of our duties is in a manner infinite, and therefore, just as in other parts of the study of nature, we should try to-- we should seek-- I'm quoting now-- "general principles upon which all of our notions of morals are founded, principles that are original instincts of the human mind, enhanced by reflection, but steadfast and immutable as components of fixed human nature."

If we don't do that, it's hard to see how we can make sense out of the fact that our duties are commonly new, we understand them, we respond to them in complicated and novel circumstances. Well, like Adam Smith, Hume took sympathy to be, as he called it, a very powerful principle in human nature and the grounding of much else. That idea was reconstructed in a Darwinian framework about 100 years ago by the anarchist, natural historian, and zoologist Peter Kropotkin, what you might call the founding volume of the sociobiology, or evolutionary psychology.

There is recent work which suggests some possible evolutionary scenarios that might have led to this development. There's a review of current work on the topic in a recent book edited by Leonard Katz of the philosophy department here. To this picture, we should add some other conceptions that have been very fruitfully studied experimentally in the past several decades. And I think can reasonably also be traced back to 17th century origins of modern science, including the brain and cognitive sciences.

One strand of this is the recognition that innate capacities are only latent. They have to be triggered by experience to be manifested. To borrow Descartes analogy, innate ideas, he said, are like a susceptibility to a disease. The susceptibility's innate, but you don't get the disease unless something happens. That's what he meant by innate ideas.

Another fruitful idea that was well examined extensively in the 17th century is that the phenomena of the world don't actually constitute experience, rather they become experience, as our modes of cognition construct them in specific ways, and therefore, they must conform to those modes of cognition. These modes of cognition are a distinctive property of our nature. They differ for different organisms. They're what Lawrence, back in the 1930s, called a kind of biological a priori differing for different organisms.

And that's also true of the experience that's the basis for the rich mental constructions that we call cultures, or norms, or conventions. The process of mental construction of experience and interpretation of it based on a fairly common genetic constitution, well, it must be rich to the extent that the structures, the outcomes are highly structured and constrained and relatively invariant, canalized, if you like. And that appears to be invariably the case when, at least, anything we understand. And if that's so, then the relativist approach is going to turn out to be profoundly innatist, at least if it is to address the kinds of questions that are studied elsewhere, the issues of acquisition and nature and use of attained systems, as, say, in the study of the visual system, or linguistic systems, or other products of organisms.

Actually, I doubt that there really are conflicts of principle separating these apparently contrasting views, rather emphasis on one or another aspect of what an individual person is, and, of course, empirical questions, a vast number and few answers about irrelevant aspects of human nature. Well, last word, final word on the import of any tentative conclusions one might entertain about human nature, one way to assess their importance is to observe how deeply they enter into conceptions of right and justice and actual struggles that these conceptions engendered. So examples of the kind I mentioned in the British case, well, may be unusual, such cases do arise quite commonly in our lives.

That's essentially what Hume was talking about. More generally, every approach to how human relations should be arranged, whether it's revolutionary, or reformist, or committed to stability, it is based on some conception of human nature, maybe tacit conception. If it has any claim to moral standing, it's put forth with at least tacit claim that it's beneficial to humans, meaning because of their nature. So for example, take Adam Smith's harsh condemnation of division of labor and his insistence that in any civilized society, government must, in his words, take pains to restrict it and mitigate its harmful effects. That conviction was based on an empirical assumption, his words that the man whose life is spent performing a few simple operations will become as stupid and ignorant as it's possible for a human creature to be, which is morally impermissible, he argued, because it violates fundamental human rights grounded in human nature.

Like other capacities, human understanding will not flourish along its own course without external triggering. It's like in Smith's words, without the occasion to exercise the understanding, and therefore, people must have the occasion, or it's an infringement on their fundamental right. That's a pretty standard enlightenment doctrine. Another one of the founders of classical liberalism, Wilhelm von Humboldt, argued that humans are born to inquire and create an infringement on the natural, this natural right, is unacceptable.

An infringement on that right would prevent them from exercising those intrinsic capacities to the fullest extent possible. Hence, illegitimate. Accordingly, as he put it, if an artisan produces beautiful work on command, we may admire what he does, but we will despise what he is, a tool in the hands of others and not a free human being acting in voluntary association with other free people. The strong popular resistance to the modern industrial system was inspired by similar conceptions.

When the system was taking shape right around here in eastern Massachusetts 150 years ago, there was a lively independent press run by artisans and shop workers, many of them young women from nearby farms. And it makes interesting reading today. They weren't borrowing from any intellectual tradition. They were expressing themselves. These are mostly quotes.

The contributors denounced what they called the new spirit of the age, gain wealth forgetting all but self. They condemn the loss of dignity and independence of Rights and Freedoms, the degradation and loss of self-respect, the decline of culture, skill, and attainment, as they were subjected to what they called wage slavery, forced to sell themselves, not what they produced, becoming menials and humble subjects of despots, reduced to a state of servitude that was not very different from chattel slavery of the southern plantations. So they felt-- these are quotes, actually. And those ideas were not at all uncommon at the time.

They were upheld in large part by the Republican Party, for example. And they were of profound concern to the masters, huge capital and intellectual resources have gone into the effort to drive them out of people's minds, very consciously. This goes back to the early days of the Industrial Revolution. And dramatically, so in the past century, when one of the major industries, modern industries, public relations industry, was created, essentially for that purpose. In the words of some of its leading figures back in the 1920s, it was created to regiment the public mind every bit as much as an army regiments the body of its soldiers to impose a philosophy of futility and a focus on the superficial things of life, like fashionable consumption, and to prevent people from harming themselves by taking charge of their own affairs, just as a responsible parent would prevent a child from running into a busy street.

All of this was justified explicitly as good for people, reflecting human nature, and reflecting the fundamental inadequacies of the less intelligent, including their unique malleability. And that's a crucial assumption that removes any moral barriers rooted in human nature that might be conceived in different ways as, indeed, it was conceived by the subjects of these benign manipulations. Conflicts over human nature, what are in our tradition called inalienable rights, they lie at the heart of the slow evolution of the human rights culture over the past few centuries. An optimist could hold, maybe realistically, that history reveals a deepening appreciation for human rights as well as considerable broadening of their range, including in very recent years.

This is not without reversals, sometimes sharp reversals, but I think the general tendency is detectable and real. Inquiry into these slow changes-- so, for example, the debates over slavery, for example, which were rational debates. Inquiry into these slow changes suggest that what may have happened could have been attainment of a clearer insight into our own basic values rooted in our nature. These are issues that are very much alive today. For example, conflicts over ratification of human rights conventions, or to take a current case very sharp and divide in the world today over unilateral military intervention for allegedly humanitarian reasons.

I think a case can be made that these are the appropriate terms for framing the issues, to some extent, comprehending the history. And it's at least imaginable, although hardly imminent, that scientific inquiry might offer some guidelines for approaching the extremely significant issues that arise, perhaps, offering some answers to questions that, as far as I can see, we can only speculate about today. Thanks.

[APPLAUSE]

KEYSER: All right. So now we're open for questions. And if you have a question, please, maybe the best thing to do would be to stand up and speak loudly, so that the entire audience can hear. And you can address it to the panel or to individuals on the panel. So we have about 20 minutes. Claude.

AUDIENCE: I have a question of Dr. Pinker, but also the panel at large. Your principles derived from the Judeo-Christian theories around me. The entire model seems to be relative to-- derived from western culture. On the parallels in eastern culture, can we substitute Buddhism, for example, Zoroastrianism, Shintoism, and come up with a similar set of conclusions? Oh, I'm done.

PINKER: The question is, are there parallel theories of human nature implicit in the other major religious traditions? There certainly are. I'm very far from an expert on them. But there is a wonderful book called 10 Theories of Human Nature by Leslie Stevenson, and I forget the co-authors name, of which, I think, 6 of them might belong to different religious traditions, Judeo-Christian, Buddhist, Confucianist, and so on, and then Marxism, psychoanalytic approach, ethological approach, and so on.

But certainly, I think every, indeed, every religion does have a theory of human nature embedded in it.

AUDIENCE: Are they similar?

PINKER: Oh, there are some-- the best I can say is that there are certainly some similarities. And the major proselytizing religions, I think, all have some notion of choice and a moral sense as part of human nature. They're not deterministic in the literal sense because that would obviate the need for a religion to tell you what to do, tell you how to exercise that choice. But that's the main one. But, again, I'm not enough of an expert to really answer that question intelligently.

CHOMSKY: If I can add a-- a good way to test the question you're raising, one way to test it is to have a look at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Human rights are founded in some conception of human nature. And the history of the Universal Declaration, the 1948 Declaration reveals that there was very active contribution from a wide variety of-- in fact, any very broad variety of religious and cultural traditions. It was not a reflection of Western values, as sometimes said.

And they managed to reach a considerable consensus on a fairly detailed accounting of human rights. Not that anyone lives up to the principles but at least formulating them as desiderata.

PINKER: One other thing. Certainly, whenever there is an articulation of what morality consists of, you get some version of a kind of golden rule ethics that is the interchangeability of the interests and rights of different individuals. I can't expect you to submit to something that I would refuse to submit to. And that, indeed, seems to have been rediscovered in a great many moral traditions.

The philosopher Peter Singer in his book The Expanding Circle argues that, in fact, moral systems, the world over, tend to be quite alike, except for one parameter of variation, almost like the linguistic parameters that Noam introduced. And that is, what is the size of the circle of entities that you count as persons and whose interests you regard as interchangeable with one's own? And, in fact, a very simple, but not oversimplified theory of the kind of moral progress that Noam alluded to is that the circle has gotten bigger and bigger, that it used to include basically your own village and then it expanded to include the tribe and both sexes and all races and eventually all of humankind.

And many current moral debates consist of whether we should expand the circle further to include, say, warm blooded animals, or animals in general, or species, should species be treated like individuals with a right to exist and respect for their interests? But the psychology of how we evaluate the moral claim seems to be remarkably parallel modulo this parameter of how big the circle is.

PUTNAM: I guess, as a professional philosopher, I want to be annoying to Steve, and say, I think the talk of a Judeo-Christian theory of human nature, I mean, nothing comes to mind. For example, he meant, well, there is a theory that humans have a moral sense. I'm trying to think whether the whole Talmud, which certainly was the lead Jewish, body of Jewish thought until the beginning of the 19th century, contains a single expression I would translate as moral sense. I don't think it does.

There is nothing in Aristotle-- moral sense theory is an 18th century theory, a 17th, 18th century theory. It plays no role in Aquinas. If you move to the Greeks, the big change, I think-- you can't translate moral sense into Aristotle's Greek, because moral didn't have the same mean-- moral is from Latin, and it's from mores, and that's a translation of the Greek ethics. But ethics did not-- but the ethical sense is not a term that would make the slightest sense to Aristotle. Where I think there is an interesting shift in the west-- well, this is to the east as well-- for Aristotle, this ethics had to do both with how we should behave to others.

And I agree with Steve-- with the last thing he said, is right. The universality of something, like a golden rule principle, does seem to be very strong. But for Aristotle, the tremendously important question was, what human flourishing consists in, a question which is of great importance to you and Chomsky. Eudaimonia is sometimes translates as happiness. And Aristotle is really human flourishing.

And one effect of the religions coming-- I think one bad effect-- and I say this as a practicing Jew-- but one bad effect of the rise of the victory of Christianity and Judaism and so on is to suppress that question somewhat, because it was supposed to be obvious, what human flourishing consists in. And so make ethics almost entirely synonymous with the question of what are your duties to others to the point where it's often said the notion of-- Bentham said the notion of a duty to yourself is incoherent.

And I think we need to keep in mind that-- well, anyway, I don't think any simple stereotype will summarize the ethical thinking of either the West or the East.

PINKER: The criticism is completely valid. To put it mildly, talking about the Judeo-Christian tradition, embraces a great many figures, ideas, and so on, so it's bound to be a simplification. I meant it really in just the minimal sense that there's a presumption that we have an ability to measure courses of action against some ethical standard, some coloring. And that's probably the most that you could get away with.

PUTNAM: Yeah, but the most common term for that was simply reason, or even common sense. [? Savara ?] in the Talmud is just the general term for common sense.