Muhammad Yunus, “Ending Global Poverty” - MIT Poverty Action Lab (9/14/2005)

[MUSIC PLAYING]

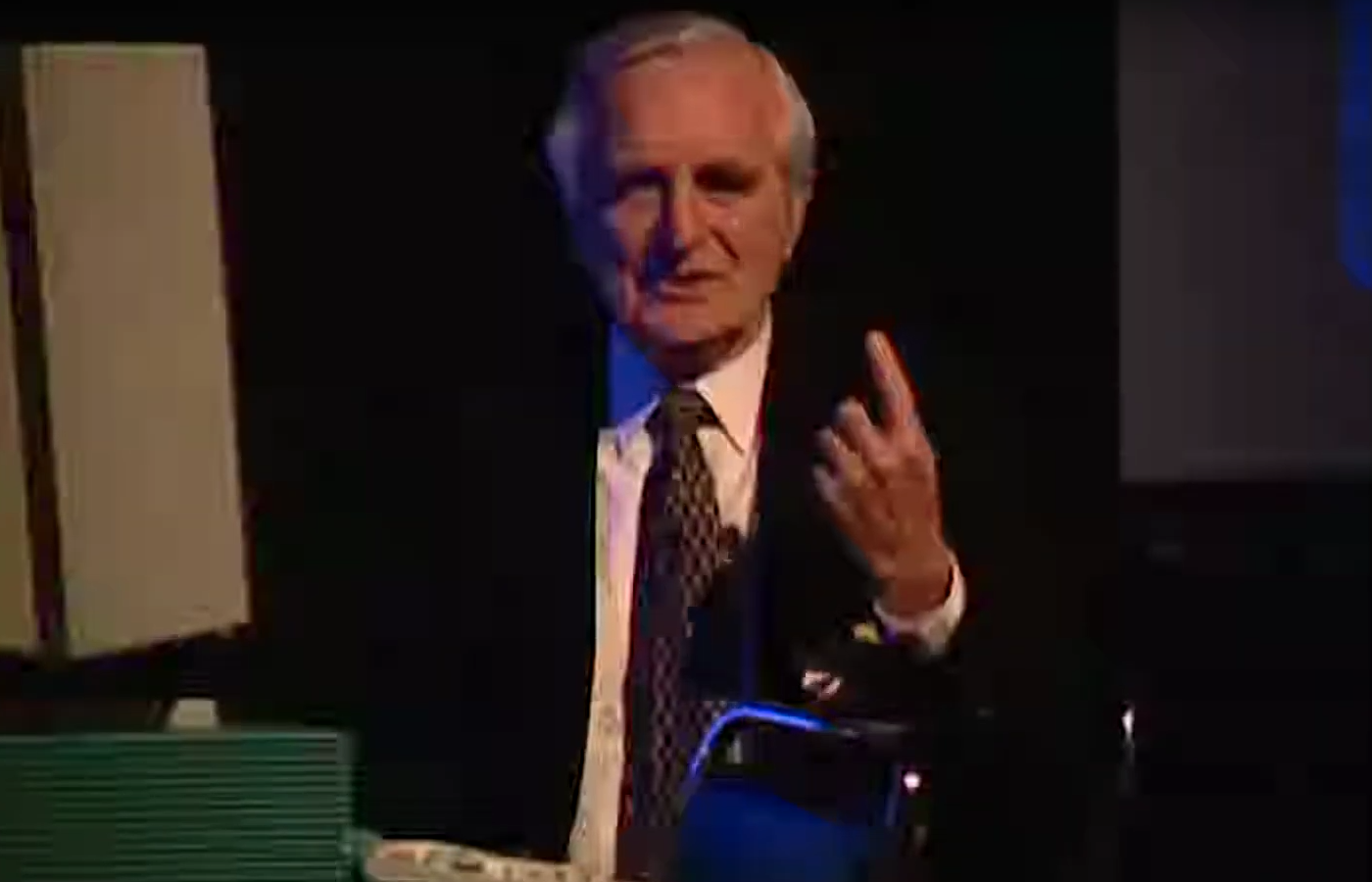

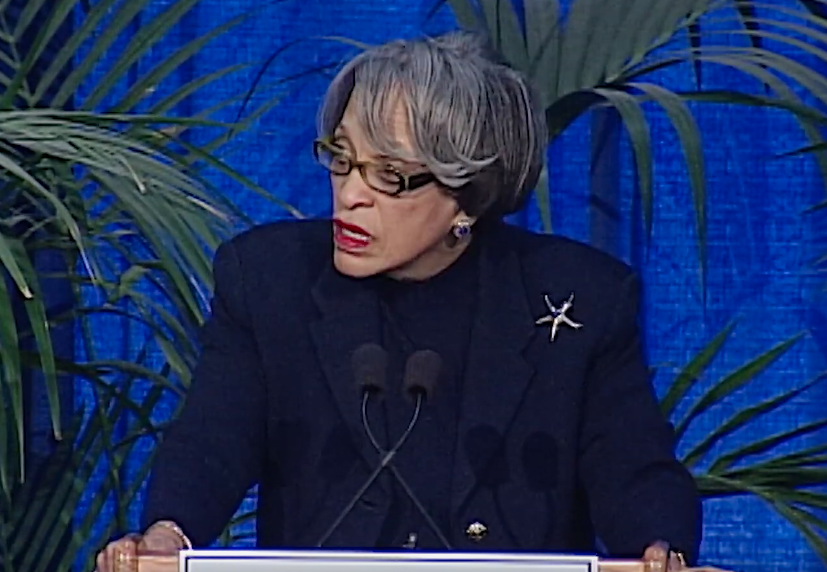

HOCKFIELD: It's great to see you all here this afternoon. For those of you who don't know, I'm Susan Hockfield, the president of MIT. And I'd like to welcome you all to this incredibly special event.

We are enormously grateful to our alumnus Mr. Mohammed Jameel for making it possible for Dr. Muhammad Yunus to visit MIT today.

He's been visiting with the Poverty Action Lab and the Department of Economics. And he's giving us this wonderful presentation on ending global poverty. It's a great honor to have Dr. Yunus on our campus.

Dr. Yunus is internationally recognized for his work in alleviating power poverty and empowering poor women. He's the founder of the Grameen Bank, a microcredit institution, created to provide the poor with tiny amounts of working capital for self-employment.

Since its launch three decades ago as an action research project, the bank has made more than $5 billion in collateral-free loans to 5 million borrowers in Bangladesh. 96% of the borrowers are women. And the bank now lends half a billion a year to the poorest of the poor, while maintaining a repayment rate of 99%.

This innovative approach to alleviating poverty has inspired a global microcredit movement that reaches out to millions of poor women on all five continents. Through this work, Dr. Yunus may well be the most influential economist in the world.

Dr. Yunus has kindly indicated that he will take questions after his remarks. And Dean Philip Khoury from the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences will moderate that portion of this afternoon's presentation. But for now, I would ask you please to join me in welcoming Dr. Muhammad Yunus to MIT. [INAUDIBLE].

[APPLAUSE]

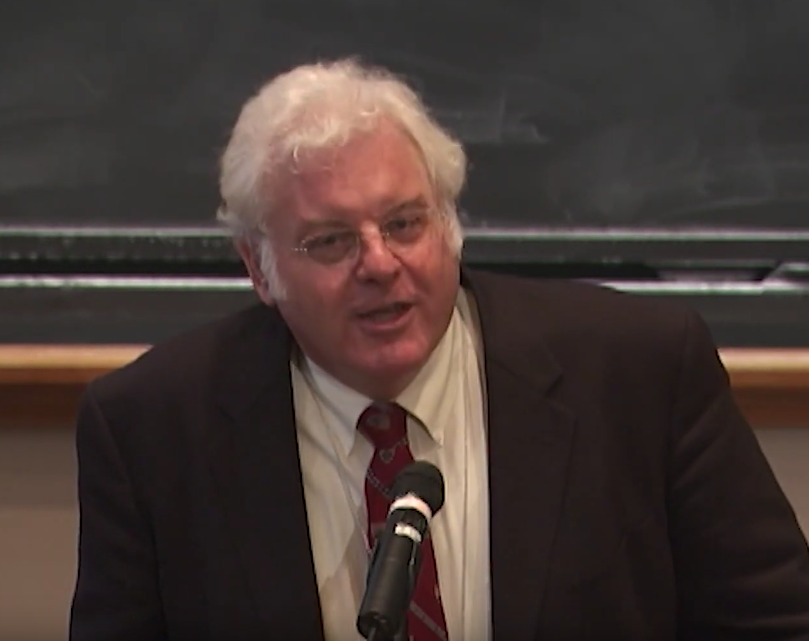

YUNUS: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you very much.

Thank you very much. It's a great honor to be here. And thank you, Susan, for introducing me. And I'm so happy to talk about the kind of work I do. It will be very brief. I hope I had more time to elaborate.

People tell me, what's so great about giving such a tiny loan to poor people? So I don't know how to answer that question-- what's so great about giving so tiny loans to poor people? So one idea that came to my mind, maybe, I thought people understand it better if I put it this way that imagine a situation where suddenly, all the banks in the world got closed, shut down, non-functional. What will happen to people around the world?

And then thinking about it, I thought this would be a good Hollywood story. You can build a good film out of it. It would be a horror movie, like Godzilla or something.

About 2/3 of the world population situation is like that. For them, financial institutions do not exist. But the horror that it should have created in their life, neither they see it nor we, the people who have banks around us, see it. Because we took it as a part of our life.

But that's what it is for 2/3 of the world population. Doors of the financial institutions have closed to them.

So their life has to be designed another way. And when you say other way, it's not a very pleasant way. Because we created a world which goes around with money. You need money at every step of the way.

If you don't have the first dollar, you can't catch the next dollars. You need $1 to catch $1. And nobody gives them the first dollar to catch the next dollar. And that's the situation, what you describe as poverty.

It's not their fault that they are poor. We simply refuse them the privilege of getting out of poverty. So when we talk about eliminating poverty in the world, we are not thinking about some people who don't know what to do in their life, illiterate, ignorant, and that's why they are poor. That's not the way it is.

They're as good human being as anybody else. As enterprising as anybody else. As smart as anybody else. But simply, they are denied of certain basic amenities to use their talent, use their creativity, use their ingenuity to move out of poverty.

So back in the '70s when I was teaching in one of the universities in Bangladesh, Bangladesh was going through a terrible famine. Famine is a horrible situation where people die of hunger, just not being able to eat. There's not food.

So it's not a very pleasant thing in a situation like that, teaching elegant theories of economics. Writing down all your equations and so on. And telling students how to overcome all the economic difficulties, empowered by the theories that we have in our textbooks. That empowerment doesn't get translated into real world just outside the classroom, where people are going through this experience of famine.

So that trip took me out of the classroom and trying to see, is there something that can be done? And out of those tiny little things, one thing that I confronted [? or ?] I noticed in everyday way in that how people suffered for tiny little money. And then, I took a student of mine, went around in the village to list people who had to borrow from the moneylender.

And when our list was completed, there were 42 names on that list who took money from the moneylenders. And the total amount for the whole 42 of them was $27. So again, imagine professor teaching in the classroom about the five-year development plan for the country. All the millions of dollars and billions of dollars you need to invest to overcome the poverty in the country.

Has no idea that few meters from that classroom, people are not waiting for those millions and billions. Their life is going through a miserable condition because of few pennies, less than $1.

So my first response was to give $27 from my own pocket, and tell them, please return the money to the moneylenders. And work whatever you want to work with this money, and be free. And that sense of liberation that came to them hooked me on.

I asked myself that if you can make so many people so happy, such a small amount of money, shouldn't you do more of it? So I was thinking how to do more of it.

I could give more money from my pocket, but I thought that only a solution, ultimately. I was thinking more something which will be generating a system. So I thought I should link them up with the bank which is located in the campus. Which I tried.

When I proposed to the bank manager, he literally fell from the sky. He couldn't believe that I'm saying that he has to lend to these people, this tiny amount. He argued, very forcibly, that the bank cannot lend money to the poor people.

Poor people are not bankable. Poor people are not creditworthy. He made all kinds of arguments, which didn't make sense to me. So I made out my arguments. It's a no-go situation, either side.

So anyway, the long story continued for several months, meeting all the bank officials, trying to persuade to take loans for the people. Nobody would agree. Ultimately, it was solved by offering myself as a guarantor. I said I'll sign all your papers, since your rules require it. And you cannot accept them because they don't have the collateral. And the banking system is built around the collateral.

So the only way I can do it is to offer myself as a guarantor. That still took another couple of months of correspondence, and discussions, and persuasions. And finally, it was resolved. And I started giving loans to the people in the village.

The bank manager said you can say goodbye to your money. This is not going to come back. I said, I'll take a chance. I took my chance. And along with it, I tried to make some simple rules to encourage them to pay back. And it worked. I got very excited that it worked because the bank manager said it won't work.

When I came to the bank manager to give the good news that everything is complete, all the money came back, he remained totally unimpressed. He said maybe you did it a few people in one village. A professor can do all kinds of miracles in one village. We don't take it seriously.

So I said, what should I do? He said you should do it in two villages. I said, OK, I'll do it in two villages. I did it in two villages. It worked beautifully. But he remains as unimpressed as he was.

So this is the story. I go on doing it, and he raises the number of villages. And after I have done it several times, then it dawned on me-- if I do it for the whole world, he will not change his mind. Because his mind is made. Banking cannot be done with poor people. And I cannot undo that mind.

I said if now he says poor people are not creditworthy, they are not bankable, I will scream. I'll scream at the top of my voice. Said that's a lie, that's not true. Because I have done it, I've seen it.

I said the real question is not whether people are creditworthy or not. The real question is what the banks are peopleworthy. And they are not. So I thought maybe I should now create a bank, which is different from the banks that I know.

And I made a proposal to the central bank, that please allow me to set up this bank which will work for the poor people. Central bank says we never heard of that kind of bank. It doesn't exist. You better go to the government.

So I went to the government, again, a long story. Finally, we persuaded the [INAUDIBLE] ultimately, and we became a bank in 1983. We were so delighted that finally we got ourselves a bank for the poor people.

So what is the difference between the bank for the poor people and banks that we know, the conventional banks? The basic difference is the conventional banks are built around the principle that the more you have, the more you can get. Which meant if you have little or nothing, you get nothing. And that's why 2/3 of the world population don't get anything.

So we reversed that principle in designing our bank. Our principle is the less you have, the higher priority you get. If you have nothing, you get the highest priority. And we think that's what the banking should be. After all, people who don't have anything, they should be the ones who should be getting something to get it started.

And then people say it may work in Bangladesh, but it will never work anywhere else. Bangladesh is a funny country. All kinds of funny things happen there. So maybe this is another funny thing.

Well, luckily, many became interested in our experience. They want to do it in their countries. And gradually, it came out in Malaysia, in Philippines, in Indonesia. We are very happy that it's working in other countries.

Today, after all these years, Grameen Bank works all over Bangladesh. We have over 5 million borrowers right now, 96% women. We lend out over a half a billion a year in tiny loans, averaging about $120 right now.

The money that we lend out comes from the deposits. It's not a bank. Some people, there's donors are giving the money, and they're distributing it. No, it's not like that. It's just like a bank is supposed to be-- taking deposits and lending money. That's what we do.

On top of it, what we have done, unlike the banks that were familiar with-- the conventional banks-- we focus on women. 96% of our borrowers are women. No collateral needed. No legal instruments are needed. So there is no legal instrument between the lender and the borrower. You don't have to sign, and notarize, and stamp, and all kinds of legal papers. We don't have any legal papers.

How does it work? You five half a billion dollars and no papers? And bankers tell me, can you sleep? I said I have very peaceful sleep. I have no problem. Said without papers, you gave all this money? What if it doesn't come back?

I said I don't worry about it because ever since we created, money always comes back. And it still does, 99%. And the 1% is not money lost. It's simply not paid within the time limit, that's all. It gets paid back, too, after the time limit. So it's a very happy situation.

We have savings, people put money into the bank. Right from the beginning, we concentrated on the children of the families of Grameen Bank. These are poor families. They don't have any education, illiterate families. So we wanted to make sure our children of Grameen families are going to school.

And very soon, we succeeded in doing that. 100% of the children of Grameen families are in school. Today, many of them are in higher education, going to colleges and universities, medical schools, engineering schools. And Grameen Bank provides them the student loans so that they don't have to worry about money for financing their education.

There's kind of a discussion of criticism that microcredit is a great idea, and it's wonderful for the poor people. But it works only for the top layer of the poor people who have some entrepreneurship, some skill. It doesn't work for the middle level of the poor people, bottom level of the poor people.

They need charity. They need handouts. Because they don't have [INAUDIBLE] ability. They don't have any skill.

We scream, that's not true. Because in Bangladesh, when we begin, our loans are less than $1, $27 to 42 people, that's our starting point. So these are not the top layer the poor people who receive this money.

And then we concentrated on women. These are not the Harvard case studies or MIT case studies of entrepreneurship. The women coming and pleading with us, please don't give me the money, I don't know anything about money. Imagine that. You go to the bank, bank said well you justify why we should give you a bank. Here we are going to the people to give money, they said, please don't give us money. So that's the kind of bank we done.

And they became so desperate, they were arguing that please give it to my husband. He understands money. I don't understand money. Some said I never touched money in my life.

So now you tell me, the entrepreneurship skill and so on, we went there deliberately addressing them, and brought them in. But still people go around saying, well, is it a great idea, but it doesn't work for the middle and the lower.

So recently what we have done is we have got fed up with this argument. We said, only way we can stop this argument by kind of dramatizing the whole thing. We said, let's give loans to the beggars. You can't be poorer than beggars. That's the last stage. Because one doesn't have anything else, so she goes on the street, beg from people for finding some food to survive.

So my colleagues ask, what do we do with them? We said, OK, let's go and talk to them. One thing we should do, find out when she became a beggar, at what point. Because this is a very important point, making a transition from a normal human life to the position of a beggar. It's not easy. So that we understand her better. And after we have learned all this, and then we sympathize and say, OK, as you go from house to house begging, would you like to carry some merchandise with you, some candies, some cookies, some toys for the kids, and give people option? Well, they will give you some food or buy something from you. If you're selling thing picks up, you think you are making enough, you think whether you should switch to selling rather than begging. It's up to you.

And they started liking this idea. And in the beginning, we thought we may have 3,000, 4,000 beggars in the program. Soon, we came up with 50,000 beggars in the program. And excitement of turning themselves into business person, you wouldn't believe what it means to them. And we tell them, look, Grameen Bank rules do not apply for you. So don't worry about all our rules. Forget it.

Only thing, this is a loan. You'll have to pay back as you can. No interest-- it's interest-free loan. So don't worry about money growing into big money. So take it. And never pay us with your begging income. That's not our money. This is your money. All we want, if you make money by selling things, then you can pay us back. If you pay back the loan, you'll be ready for another loan. People understood it very clearly.

A typical loan for beggars is $9. Imagine, with $9, people thinking about a business idea and how to bring herself out of the begging. Out of this-- now that it's ongoing program, we have about 1,000 beggars who are no longer beggars anymore. They are business people. We said our success would be if we can see, within a year, within six months, 3,000, 5,000 have come out of begging. I said, this is-- and what a message for all of us that people can pull themselves out of all kinds of situations, given an opportunity.

So this idea of giving loans and building up this kind of financing institution caught up globally, and in many countries is being used. This also led us to think about other things, information technology for example. We thought not only microcredit is important, microfinance is important. Information technology is also important for poor people. We got an opportunity, and skipping the whole story, we created a mobile phone company called Grameen Phone.

Everybody-- that's a crazy idea. You are lending money to poor people. Why do you want a cell phone company? We said, we want to bring cell phone in the villages of Bangladesh, and give loans to the poor women so that she can buy herself a cell phone and start selling the service of a cell phone in the village and make money.

Who is going to use the cell phone in the village? I said, whoever wants to make a call to anybody. Everyone thought, this, it will never work. But it became a rolling business. Women took loans, started selling service in the village. And many villages in Bangladesh have no electricity. 70% of the population of Bangladesh do not have access to electricity. So how do you bring cell phones in the village where there is no electricity? And most of the villages don't have electricity.

We promptly came up with an idea. Solar panel, that's it. So we started plugging into solar panels. So now everywhere [? it helps, ?] mobile phones. There are 170,000 telephone ladies in Bangladesh selling service of telephone who never saw telephone in their life, never heard that there is a gadget called telephone. People used to tell us, well, you're giving money to the women, OK, all she can do all her life is to raise chicken, or make basket, or raise a cow. Because she cannot come out of the traditional technology, ever. So when we wanted to give telephones, they said, no way, she will be scared. And I was always arguing that don't underestimate the talent of human beings. They are very creative people. There is no difference between the poor women and anybody else.

So that is only something in an idea. But it's wonderful to see that people reacted exactly the same way. Now today you go and talk to any telephone lady in Bangladesh, you can make a call from here.

[AUDIENCE CHUCKLING]

They talk in the business language. She talks as if she was born with a telephone in her hand. She knows everything, ins and outs of a telephone. What a confident person she is.

People ask me, what is this that you see as poverty? How do you define poverty? I said, I don't know how to define poverty. But to me it's something that I see as a kind of image which comes close to my mind. It's a bonsai tree. That bonsai, little tree, I say poor people are bonsai people.

You choose the tallest tree in the forest. It's a beautiful tall tree in the forest. And pick up the best seed for that tree. And plant it in a flower pot. What do you get? Tiny little tree. It doesn't grow very much. It looks exactly like the tree you saw in the forest. It's a small replica of that tree. Is there something wrong with the seed of the tree? No, we picked the best seed. Then why is it so small? Because we plant it in a small flower pot. We didn't give the tree space enough to grow. So it's not the fault of the seed, it's the space denied.

Poor people are just like that tree. They're as good human being as anybody else. Simply they are not given the space. So the poverty is not created by them, it's created by the institutions we built. Banking institution is one. Policies that we pursued, even the concepts that we design and we discuss in our classrooms, ultimately impacts on the society that we create.

So if you want to get the poverty out of the world, you have to redesign those concepts, redesign those theoretical structures. If you fix those things, nobody will be poor person. Because their ability to take care of themselves is inside of them. All human beings have unlimited potentials. Most of us in the world scratch only the surface, and the poor people never even scratch the surface.

So the gift each human being has inside of them, among the poor people, that give remains unwrapped. It's been packed. It never gets opened. So when we talk about microcredit or all those things that I'm talking about, this gives an opportunity to make a little bit of openings, find out who I am. And that's the one-- that's the important thing, to see what is inside of me and how much of it I can bring out. And if you can allow that, if you can create that kind of society, there's no reason why anybody should languish in that misery and suffering.

And one way to do it-- I'll quickly stop at that-- is to redesign the concept of business. The business today is understood everywhere, in our textbooks, in our theory, in our real world. Business mean business to make money. I said, interpretation of human beings in that way is a very limited way. Human beings are much more-- it has much more variety inside of a human being than just that. Human beings cross the whole range of feelings, whole range of dimensions inside of them. So I said, if we could include, in a idea of business, as two kinds of business. Business to make money is one, business to do good to other people is another one. We can run business to do good to people. These would be businesses which are not concerned to make profit, but to reach out to people, solve social problems in a business way.

These are non-loss companies. It doesn't lose money. It's a break-even company. Could be done. And we can address most of the social problems in a business way. If we can put them in a business way, social business, this we can call social business-- if we can make social business enterprises, a lot of problems can be addressed that way. Problem of poverty-- like microcredit, for example, can be addressed that way-- problem of children suffering, child labor, livelihood creation, crimes, drinking water, sanitation, health care, and social business enterprises.

We need social business entrepreneurs. People say ah ha, I want to do this. This is a challenge I want to take. I can design things and I can run a business, not for me to make money, but to reach out and solve the problem. So this is a challenge. This is an idea what I think time has come to address lots of problems that we see around ourselves. And thank you very much. I'll stop here.

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE CONTINUES]

Thank you. Thank you very much. Thank you.

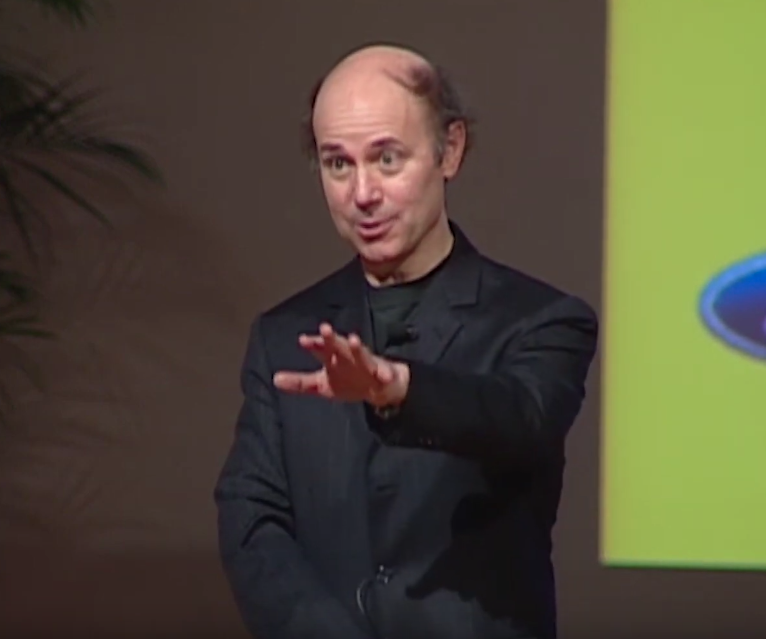

MODERATOR: We don't have much time. Unfortunately Dr. Yunus has to head back to New York. It's a busy week for him. So we have microphones somewhere here. Yes, here and there. And so if you would please come up. And I'm sorry, it's the only way we're going to be able to hear you. And if you'll just line up, and we'll try to get as many of you in. Be as brief and concise as possible. Thank you. Please go ahead.

AUDIENCE: It's a very inspiring thing you do for all those people. I had a practical question, which is how specifically do you guys actually run the operation? How do you collect, how do you determine how much interest you charge and how much interest people get in their deposits?

YUNUS: I will have a one full-blown lecture for that. We have branches. We have over 1,600 branches in the country in Bangladesh. Each staff is responsible for a certain number of borrowers, to take care of their needs and so on. All Grameen Bank activities are organized around building five-member groups. Five people form a kind of a business circle. And several of those groups together create what we call a center. The center meets each week where the business is transacted.

Our basic principle is people should not come to the bank, the bank should go to the people. So we always go to the people. Every week, we meet all our five million borrowers at their doorstep, and do the business at their doorstep. And all our loans are paid back in weekly installments. So this is basically the operational details.

AUDIENCE: And what's the average interest rate you charge people?

YUNUS: Interest rate, we try to be as close as possible to the market interest rate. Market interest rate today in Bangladesh is about 14%. We have four interest rates in our work. One is 20%, which is 6% above the market rate. And the next one is the housing loan. Housing loan is 8%, which is way below the market rate. And next one is 5% for the student loan, which is again way below the market rate. And for beggars, it's 0%. So together we are close to market rate.

And we also a deposit collector. So on our deposits, we pay 8 and 1/2% interest on deposits, minimum. And it goes all the way to 12%. So we pay 8 and 1/2% to 12%, and we charge 20%, 8%, 5%, and 0%. That's it.

AUDIENCE: Thank you.

YUNUS: Thank you.

MODERATOR: Please.

AUDIENCE: Hello. Thank you, Dr. Yunus, for your comments and for all your work. My name is Raven. I'm from the Fletcher School. And with all the kind of enthusiasm surrounding microfinance right now, I've heard it said as a word of caution that microcredit especially, offered first to the poor, can really cause harm to those who are in need of it. And I'm curious, just as your comments and advice to those enthusiastic about microfinance, what are you doing and what do you recommend should be done in the way of offering other interventions to ensure that this capital provided to them doesn't in fact indebt them. Thank you.

YUNUS: Yeah. One thing to be careful when you give loans to people, we try to make sure that this money is used for income-generating purposes. Money should create money. Once you consume it up, take the money, and then you create yourself the obligations, and the debt burden, and all kinds of things. So that's why we created all of those groups and so on. You can mutually oversee each other's activities so that you don't use the money in the wrong way. Because we give loans for income-generating activity.

So you have to demonstrate, you have to explain to your own group members what you are going to do with the money, how this money will bring money for you. Bank doesn't approve the loan. Basic approval is done by her own friends. So she has to explain everything what she is going to do so that they can go and check it out. So this is one way we see to protect them from using up the money in the wrong way.

AUDIENCE: Are there any other activities such as capacity-building, or market value chain improvements, or productivity-enhancement activities that the bank does along with the lending?

YUNUS: We don't have any program of training as such, but we try to connect them with each other. If you are doing something, and somebody else is doing the similar thing in the next center, we say, ah, she is doing this, why don't you get together and see what do you do. They learn from each other much faster. And one thing comes because of some kind of jealousy that she is doing so good and I'm not doing it. So she would like to be equal to her. So this is also good. This is a creative jealousy that she tries to get even with her and prove that she can perform better than her. It's a neighborly jealousy. That works pretty well. And we encourage-- we always give examples of what others are doing, so that she feels--

[AUDIENCE CHUCKLING]

She feels, ah ha, how can she do that? But thank you.

AUDIENCE: Thank you.

YUNUS: Yeah.

AUDIENCE: [INAUDIBLE]

MODERATOR: Please, one question each. No follow-up. I'm sorry-- just to allow everyone a chance.

AUDIENCE: Hey, Dr. Yunus, Juan Garcia from ICIC. Thank you for coming and speaking to us. I read your book, felt very empowered, [INAUDIBLE].

My question is, in your book, you touch a little bit about the example of microcredit financing here in the US. And it seems it was not as successful as we had expected. So in the wake of Katrina, and with all the people left behind with nothing, how can an example like yours become relevant?

YUNUS: Very much. I just wrote an op ed-- I don't know if anybody published it yet-- mentioning that. Because Bangladesh has lots of experience of going through floods and disaster. This is our normal life. We face this all the time. So we had to learn this over time. One of the things we find very useful in a situation of disaster-- microcredit-- to build it back again quickly, because of all the mechanism is set to get you started all over again, put you on your feet.

Here, [INAUDIBLE] this would been an occasion in New Orleans. Tried two things-- one is microcredit, crediting channels so that people can go back and start their life all over again, build their houses, build their livelihood and so on. Another one, this is a good opportunity also for building up social business enterprises, social entrepreneurs coming-- social business entrepreneurs coming and designing things in a business way to address these issues. Money going as a handout, as a giveaway sometimes don't achieve the purpose for which you do. But if you are doing it in a business format, it works much faster and much efficiently. So this is one occasion I would think would help enormously.

MODERATOR: Please.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. Many of us are familiar with the arsenic in the drinking water in Bangladesh. And I'm wondering if you have taken any steps to apply your philosophy to empowerment of women in providing safe drinking water.

YUNUS: Yeah. We try all the time. This is a terrible thing that we have been going through. Grameen Bank has encouraged people to have tube wells. We gave loans to have tube wells. At that time, we had no idea that this is going to lead to another kind of problem. UNICEF was so enthusiastic about tube wells. We thought, we should have tube well for every single family in Grameen Bank, which we generously kind of promoted. So now we feel guilty that this is being the source of such a terrible thing, arsenic.

So quickly, what we did, like others have done, kind of classify those tube wells which are-- arsenic content is so high that it's not usable for drinking purposes. Which, others are still usable because arsenic problem doesn't exist.

Once we have done that, then we have, on a second level, where the arsenic exists, how to clean it up. So there are certain methods now. [? As a ?] pitcher-- three-pitcher system which we encourage. And then encouraging them to go into rainwater harvesting. People are not familiar in rainwater [? harvesting. ?] Bangladesh is a country of rains. In monsoon, we get enormous amount of rain. But people don't drink rainwater because there's water everywhere. So now we're encouraging them to build rainwater harvesting system and purify the surface water. But it's still the real answer has not come. Arsenic is still a major problem. We are still working on it.

AUDIENCE: But you are providing loans for that.

YUNUS: Pardon? Yes, we provide loans. Loans, that's no problem.

AUDIENCE: But that is not--

YUNUS: It's the technology that's the problem right now for us.

AUDIENCE: But that is not generating income, is it?

YUNUS: No. We give housing loan. It's the same old thing. We have given housing loan. We have gone to debate. Everybody said, you don't give housing loan because it doesn't generate income. We said, no, it generates income. It's a very productive loan. If you can sleep peacefully, that's very good. This gives you the energy to do that.

And for women-- because our borrowers are women-- the house is also our factory. That's where she works. So if you cannot-- if you leave this roof open, she can't work. So it's very important.

So what is productive, what is non-productive is something that you have to decide in the context of the situation. So simply say, drinking water is not productive, it's wouldn't be a good thing to say.

AUDIENCE: Thank you.

MODERATOR: Thank you. Please.

AUDIENCE: Hi. What kind of results have you find in impact evaluation related with poverty alleviation with the loans compared with groups that haven't received the loans?

YUNUS: Yeah. There are lots of studies done on Grameen Bank, on many, many different issues. Grameen Bank became a very attractive research subject for many reasons-- for women, for credit, for poverty alleviation, for health, and so on. So in all this, they have uniformly came to the finding that people in Grameen Bank have moved out of poverty consistently.

One World Bank study gives a very specific number. They said, 5% of the Grameen borrowers come out of poverty every year. And we have been trying to make sure not only 5%, that speed, can we make it faster so that larger and larger percentage of Grameen borrowers get out of poverty each year, and each month, each day, each week. Because people don't wait until the end of the year to get out of poverty.

[AUDIENCE CHUCKLING]

They get out every day-- one family today, next family tomorrow, depending on where you are. So we want to see that happening.

Another study shows that getting out of poverty starts as soon as about five cycles of loans. But there may be families which takes 15 cycles of loans still in poverty. So we are trying to see how to reduce that 15 cycles to come down to 10 cycle, and fifth cycle to come to the fourth cycle, so that the range in between becomes shorter and shorter, people, all kinds of people come.

And we see the reason it's prolonged for many families is sickness, disease. So the health became another worry for us. We still can address that health issue. And that's, we see, the challenge for anybody who is interested in poverty alleviation, how to address the health care services to come to the poorest people in an affordable way so that they can get out of the health problems that they suffer.

Poor also means poor in health. It goes together. So now you have to address it simultaneously. We are addressing one part, but we still couldn't get to the health part. So this is where we are now trying to say, can we build, in a Grameen-type health care in a virtual way within Bangladesh, to build it up in a way that nobody is left out of health care system.

MODERATOR: We're going to have time for a couple of questions. I'm very sorry. Please, so we'll just go as far as we can. We have five minutes.

AUDIENCE: OK. Mr. Yunus, thank you for your inspiring talk.

YUNUS: Thank you.

AUDIENCE: When you told your story, I couldn't help but think that the banker you approached might feel like IBM does after meeting with Bill Gates.

[CHUCKLING]

I have two quick questions. You can answer whichever you like. You said--

YUNUS: You give me options.

AUDIENCE: Yes, options are good. Now, you said you had an original set of rules when you made the first small leap. If you could go into detail about those rules that you had for the first 42 of your borrowers. And two, do you have any advice for people who are thinking of replicating a similar scheme for microinsurance? Because given the disasters that take place, people often lose their livelihoods. And we've had discussions-- students-- about microinsurance. Thank you.

YUNUS: Yes, microinsurance is a very important thing. Let me take the microinsurance part of it. We have been providing health insurance. We have developed a health care system, but in a limited area. We are trying it out. I'll explain a little bit more. Each Grameen Bank family in that area where we have the micro health-- insurance can join the insurance program by paying about $3.00 a year. If you put $3.00 a year, entire family comes under the health care insurance. And for that, you have a fully-qualified doctors in the area, and the paramedics, and health workers, and you can buy medicine at 25% discount, and you have pathological lab right there, and so on.

So today, in the 20 areas that we work, we cover about 90% of our cost in expenses that we have to incur. So still have a 10% gap. So we are trying to see if we can come to the 10% recovery so that we can expand it globally, all over Bangladesh. Because we cannot expand it globally if you have to subsidize it from the resources that we have. So this is where we are looking for-- this is the health insurance part.

Then we have the loan insurance. Loan insurance is simply if a borrower dies and she lives behind-- of course she leaves behind the loan amount. Under this insurance, entire loan amount is paid off by the insurance, so the family doesn't have to worry about it.

And not only it's a financial relief for the family, it's also a great satisfaction for the borrower herself when she is alive. Because she feels, when she dies, she can go very clean to God. She has not left behind any loan obligation. Because this is a part of their religious feeling that if she leaves behind a loan, God will be extremely unhappy with her. Until somebody takes care of that loan, she has to suffer.

So now she feels very happy that the insurance takes care of everything. She feels that I have not been creating any burden on anybody in my life. When I am dead, I don't want to leave any burden on anybody else. I can go clean.

So that's loan insurance. Another one is life insurance. We also have life insurance coverage. So this is loan insurance, life insurance is universal within Grameen Bank. It's already there. But the health insurance is for just a limited experiment we are doing. We hope we will be successful in that. Thank you.

MODERATOR: Thank you. I think that's all the time we have. I'm very sorry. Please.

HOCKFIELD: Well, this has been an extraordinary afternoon. And I want to remind you all that none of these things happen by virtue of a single individual. And we owe an enormous amount of thanks to our alumnus Mohammed Jameel from the class of 1978 for making it possible for Dr. Yunus to be with us today. MIT, we pride ourselves by saying we're the kind of people who solve problems. And I cannot tell you how inspiring it is to see how one individual, through intelligence, initiative, persistence, has made an enormous inroad in one of the world's greatest problems, which is global poverty. I want you to please join with me in taking Dr. Yunus once again for an inspiring talk.

[APPLAUSE]