26th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration at MIT - Shirley Ann Jackson

MERRITT: Good morning, everyone. My name is Carla Merritt, and I'm currently a junior pursuing a degree in chemical engineering. I will be your mistress of ceremonies during this morning's celebration. Welcome to the 26th annual Dr. Martin Luther King Junior Celebration. I would first like to take this opportunity to thank President Charles Vest and his wife, Rebecca Vest for hosting this event.

[APPLAUSE]

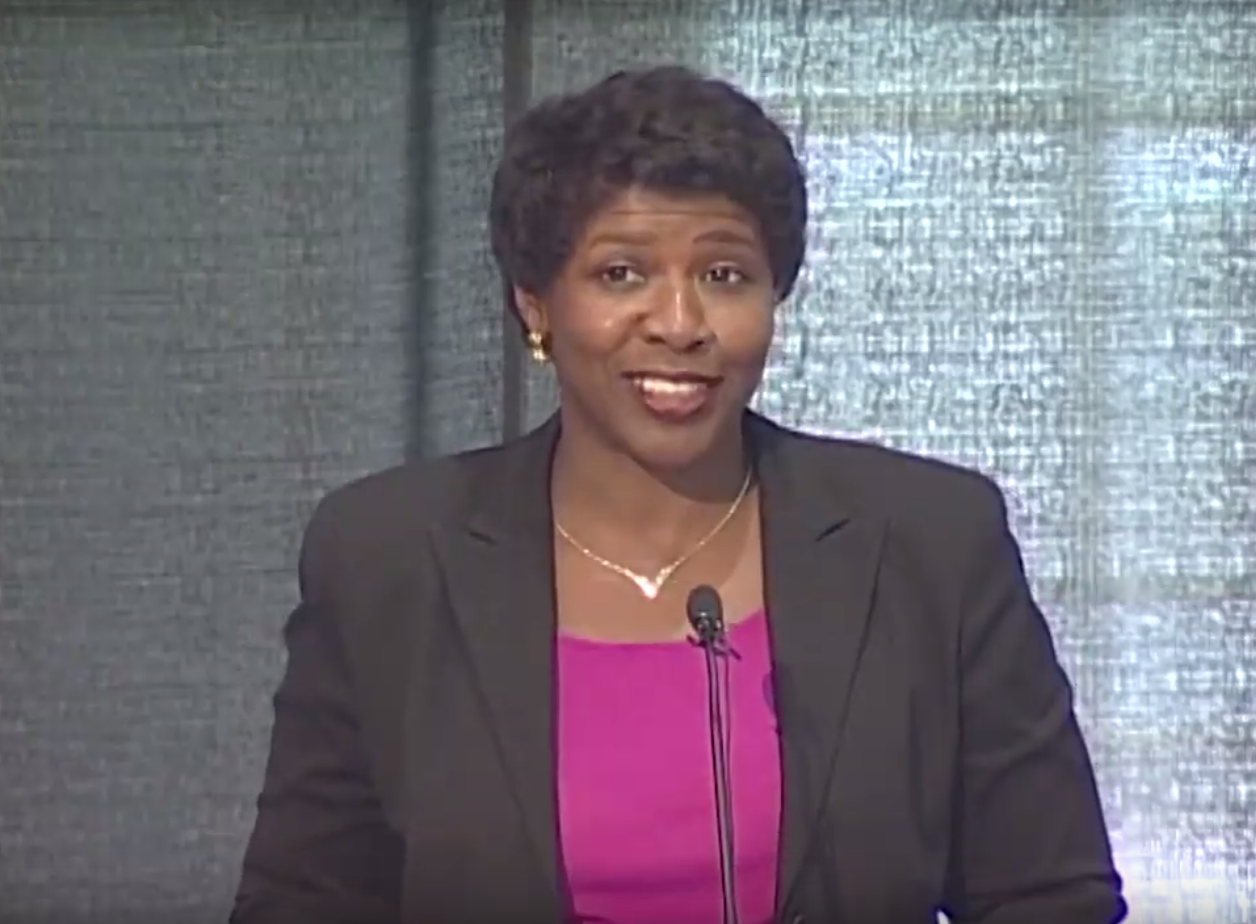

I would also like to welcome Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson, President of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, MIT class of 1968 and 1973.

[APPLAUSE]

It is a pleasure to have you here this morning. Furthermore, I would like to thank all the members of the Dr. Martin Luther King Junior planning committee, to whom we owe this wonderful event.

When I call your names, please stand so that you can be recognized.

Professor Jerome Freeman. Professor Richard Milner. Professor Wesley Harris. Assistant Professor Melissa Nobles. Assistant Professor Larry Anderson. Associate Dean Arnold Henderson Junior. Assistant Dean Ian David Shaw. Ronald Critchlow. Reverend Jane Gould. Ivett Lane. Trudy Morris. Paul Paravano. Robert Sails. Toby Weiner. Associate Provost Philip Clay. Special Assistant to the President Dr. Clarence G Williams. QueAnn Thomas. Felix Ayoung. And co-chairs, Dean Leo Osgood Junior. And Professor Michael Pheld.

In addition, we would like to express our appreciation to the students who were here early this morning to help with the preparations for this event. Thank you all for contributing to the success of this morning's event.

We will now have a selection from the MIT Gospel Choir, Lift Every Voice and Sing by James Weldon Johnson. We asked you to join in and sing the first verse. Please stand and join hands as the song is sung.

(SINGING) --voice and sing till Earth and Heaven ring, ring with the harmonies of liberty. Let our rejoicing rise, high as the list'ning skies. Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us. Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us. Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, let us march on till victory is won.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us. Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us. Facing the rising sun of our new day begun. Let us march on till victory is won.

[APPLAUSE]

MERRITT: Thank you, MIT Gospel Choir for that outstanding rendition of Lift Every Voice and Sing.

[APPLAUSE]

We will now begin the program with the invocation delivered by Reverend Jane S School. Following the invocation, breakfast will begin.

After breakfast, we will have two students-- Ibrahim Fontaine, class of 2003, and Tamara Williams, a graduate student. They will lead us in reflection on the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Junior.

Then we will hear remarks from President Charles N Vest. And he will have the distinct pleasure of introducing our keynote speaker, Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson. Chancellor Lawrence S Bacow will present the 1999-2000 Martin Luther King Junior Leadership Awards.

Following that presentation, Provost Robert A Brown will recognize the 1999-2000 Martin Luther King Junior visiting professors.

Now, let's begin our program with the invocation by Reverend Jane Gould. Right after Reverend Gould's invocation, we will begin breakfast. Reverend Gould.

GOULD: Oh mortal, what is good and what does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your god. As the prophet Micah asked the people of Israel in the eighth century before the Christian era, so must we ask ourselves at the dawn of the 21st century. We gather this morning to reflect on leadership-- bold leadership, connective leadership, transformative leadership.

Last Friday, I accompanied my son's fifth grade class on a field trip to the Kennedy Museum. As I watched the videotape of Martin Luther King Junior's I Have a Dream speech, and read the documents of the civil rights era, I realized that I was the age of my son when I heard King preach in the National Cathedral on the last Sunday of his life.

Concretely and graphically, I understood that a generation has passed, and King's dream remains unfulfilled. In his 1963 letter from the Birmingham jail, King wrote, let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away. And the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear-drenched communities. And in some not too distant tomorrow, the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson stands before us today as evidence of the progress made, as well as a challenge to stay in the struggle so that we might transform the face of leadership for the new millennium. Yet for all of us gathered here, there is an inherent risk in heeding the words of the prophet Micah, and taking to heart the commitments of Dr. King.

King's mentor, the Reverend Dr. Howard Thurman wrote, the reassurance of a secure income, the quiet glow of working with a safe and respected institution in conventional ways, this sense of well-being that comes from being accepted by everyone because one's thinking is sensible and safe-- all of this makes for a certain kind of deep tranquility. But there is apt to be no growing edge and very little of the tang and zest of aliveness that only the adventurous spirit knows. It is not an accident that the messengers of the gods were symbolized as human beings with wings, ages before we thought of the possibility of flying through air. The god of life is an adventurer. And those who would affirm their fraternity must follow.

And so we give thanks this morning, for the food that strengthens our bodies, for the dazzling array of bright minds that stimulate our thinking, and for the presence of committed individuals who inspire our action, that we might be holy adventurers, seeking, justice, doing kindness, and walking humbly with our God. Amen.

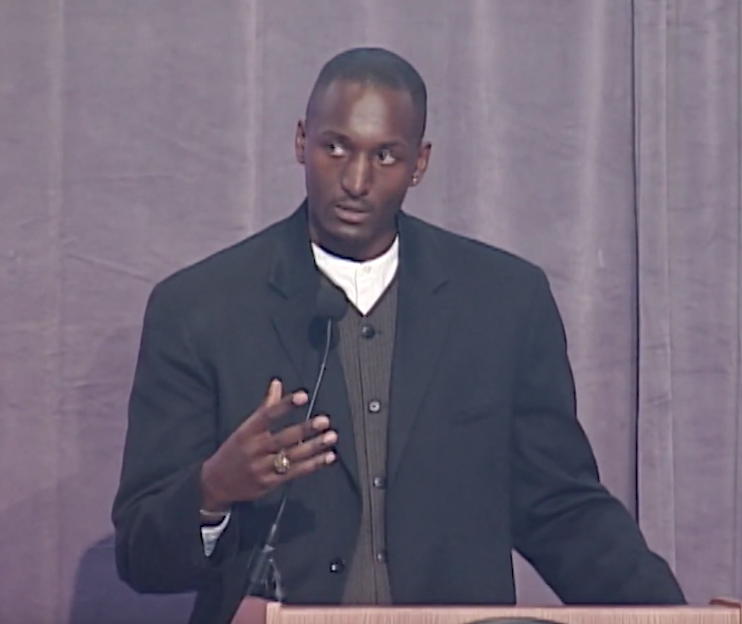

FONTAINE: Good morning everyone. My name is Ibrahim Fontaine, and I'm a sophomore in the mechanical engineering department. When I heard this year's theme for the annual Martin Luther King Junior Celebratory Breakfast-- engineering bold leadership for the 21st century-- the first thoughts that came to my mind were community, initiative, tenacity, and manhood. These are all qualities that I feel were possessed by the man we are celebrating here today.

Immediately, the question arises, how will we, people of color, display leadership within our community in order to make a positive change for the 21st century. Being college students at a preeminent university, we are in a powerful position to make a strong influence.

Dr. King was a bold leader-- I think this goes without saying. Yet part of what made Dr. King such an exceptional leader was the dynamics of the community that he served. These dynamics of the black community have changed over the years. Yet there has to be a sense of community in order for us to understand the need that currently exists. Otherwise, the great historical and cultural ties that has connected us as a people will be lost, and a permanent separation will exist within our community between those who have and those who do not.

This brings me to my second and third thoughts on this on the theme for this year's breakfast. Positive change does not occur without effort. In order for us to show leadership in the 21st century, we must possess tenacity and initiative. One of the greatest dangers I see within my community is complacency. We can not become satisfied with current situations.

Dr. King possessed both tenacity and manhood. His hunger and desire to end the plight of black people was inspired not only by his personality, but also by his relationship with God. We too must possess this tenacity. The greater the level of spirituality that exists within our community, the greater initiative and understanding for change will exist.

I want to make my final point by addressing a subset of our community. The quality that we as men of color must possess is manhood. Today, as men of color, we are still viewed by society as public enemy number one. All too often, society attempts to emasculate us by directly associating our face with crime. In order for us to become positive leaders in the 21st century, we must assert our manhood, as Dr. King did during his non-violent protest for civil rights.

Out of all the words I've used, I feel that this is the most difficult to define or explain. However, I have a few thoughts on what I feel it exemplifies. Manhood means changing the negative to the positive. Manhood means fulfilling all responsibilities. Manhood means controlling your environment and not letting your environment control you. Manhood means defending and securing resources in your community. And finally, defining yourself and not letting yourself be defined or dictated by others.

These are the qualities we must possess in order to engineer bold leadership for the 21st century. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

MERRITT: Thank you, Ibrahim, for those inspiring words. Now, we'll proceed with Tamara Williams. Tamara.

[APPLAUSE]

WILLIAMS: Good morning, everyone. Today, I will speak to you on the subject, when shall we arrive.

Death-- the point of no return. You cannot escape the fact that death will someday come knocking on your door. Many of you will have lived life to the fullest, having achieved your spiritual professional and personal goals. Yet some of us, our lives will be cut short, snatched away without warning.

Such was the case with the man whom we commemorate on this day. Dr. King stared death in the eye each time he took a public stand for the civil rights of colored people. I could imagine the 23rd song resonating in Dr. King's mind. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for thou art with me.

On the night before Dr. King's death, he stated with tears in his eyes, like anybody, I'd like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned with that now. I just want to do God's will. Dr. King refused to stray from the path of equality and justice for all, and a society built on total inclusion.

The year 2000 is upon us, and we have yet to answer Dr. King's cry for equality. Any given day, we can pick up a newspaper, and read about a young black or Hispanic man who has been gunned down like an animal, because the police thought he had a gun.

Just the other week, officer C Cornell Young Junior was shot by his colleagues because they mistook him for a criminal. Mr. Young was not shot once, but three times in the head, the chest and the abdomen.

And time would fail for me to mention that countless Native Americans, Africans, African-Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, Asians, Hispanics, Chicanos, and Latinos who have been beaten, tortured, maimed, lynched, and raped, because we appear to be a threat to the social structure of this great country.

Furthermore, technological lynching continues to exist at our finest universities. Administrators, faculty, and staff continue to ignore the exclusion of minorities, which is just as dangerous as placing a noose about our neck and hanging us from a tree.

I don't know about you. I don't know about you. And I don't know about you. But I don't need to see another cut person of color gunned down, beaten, or dragged to their death for me to realize that America has a need of racial tolerance.

In President Clinton's State of the Union address, he said, we should do more than just tolerate diversity. We should honor and celebrate it. This echoes the legacy of Dr. King, who fought for equality.

I want you to go away today, thinking about the fact that it has been less than 50 years-- less than 50 years-- since people of color have required legislative civil rights, as opposed to rights obtained through those committed to high ethical principles.

A society built for hundreds of years on the premise of segregation, discrimination, and racism is not capable of radical change, unless the powers that be insist on correcting past wrongs. Until we can bravely face this fact, Dr. King's dream will remain just that-- a dream, a dream, a dream. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

MERRITT: Once again, I would like to thank Ibrahim Fontaine and Tamara Williams for letting the words of Dr. King be heard once more. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Now, I have the honor of introducing the 15th President of MIT, Dr. Charles M Vest. President Vest will give some remarks, and proceed to introduce our keynote speaker, Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson.

[APPLAUSE]

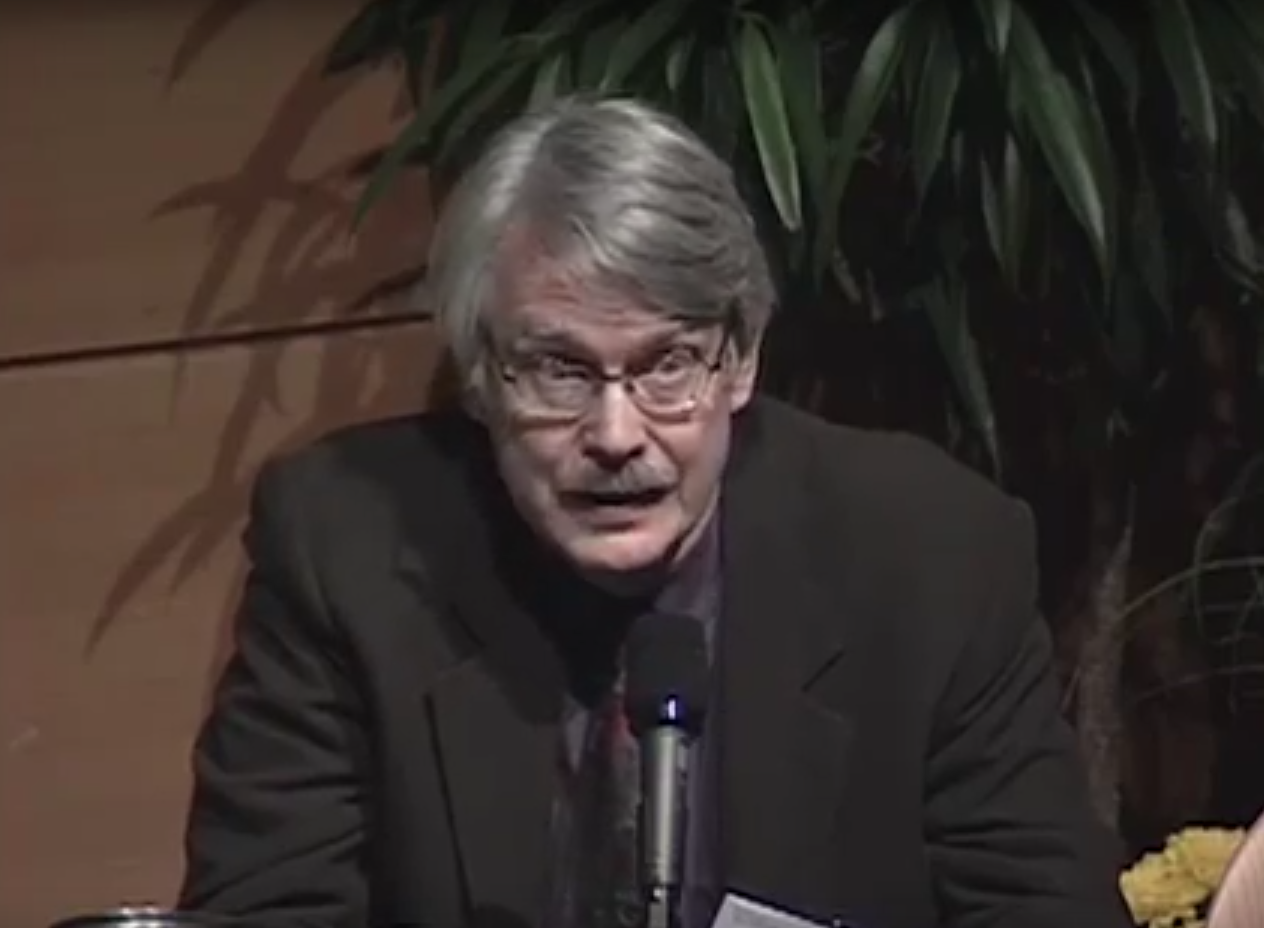

VEST: Thank you, Carla, and good morning. Before I begin my remarks, I'd like to take just a moment to recognize two distinguished representatives of the larger Cambridge community who have joined us for this morning's program. Representing the Cambridge City Council, I am pleased to welcome our mayor, Ken Reeves. Ken.

[APPLAUSE]

And here today representing the city of Cambridge as well is police commissioner, Ronnie Watson. Mr. Commissioner.

[APPLAUSE]

MIT is committed to working closely with the city of Cambridge across the full spectrum of educational development and civic affairs. We share a common responsibility to fulfill Dr. King's vision of a strong, mutually supportive community. We are pleased that you can join us in rededicating ourselves to that shared goal.

A few years ago, Becky and I were privileged to be invited to dinner at the home of UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. As you know, the Secretary General is an MIT alumnus. It was a glittering and, for us, very memorable evening.

The dinner was held to honor the outgoing president of the UN General Assembly, who in asked to make a few informal remarks, began by saying something along the following lines-- the General Assembly is a collection of brilliant and talented people. But what do we do? We dress nicely in pinstripe suits, and talk politely and endlessly about a number of matters in the gracious and dignified manner. Most of us become good friends. And we certainly have a lot of mutual respect.

But we never talk about the real issues. The hard things that should be bluntly confronted. Perhaps in academia and here at MIT we are too guilty of something along these lines. We gather annually to celebrate the legacy of Dr. King and to remind ourselves that although the path is long and hard, and the goal seemingly distant, we have much to be grateful for. And many triumphs and heroes to recognize and thank.

Most of all, we gather to express our pride in our remarkable students, with whom we work and learn and lead. I look forward each year to this celebration, and its sense of vision and recommitment to the cause of building a just society.

Today, however, I want to follow the diplomats advice, and talk about a really hard issue. One that many of us in this room know and worry about, but rarely talk openly about. One for which I certainly admit upfront, I don't have the answer.

The issue is the gap between ability and achievement of far too many minority students in American colleges and universities. We in leading colleges and universities have two fundamental duties toward all of our students. First, to seek and admit talented accomplished and motivated young men and women. And second, to provide a learning environment that enables them to realize their highest academic and personal potential.

Last year at this breakfast, and in a subsequent Boston Globe editorial, I discussed the misguided movement in this country away from explicitly considering race as a factor in admission decisions. The core of my message, and indeed MIT's message, was this-- we believe that considering many factors in admissions, including race, allows us to build a class that promotes the best educational experience for all of our students. And that it increases our ability to help build a strong coherent and productive society for the future.

We must sustain these principles. We must continue to publicly champion the critical importance of diversity in college admissions and campus life and learning. And we will. The fact is that by applying these principles, we do get the right students. They represent an extraordinary variety and mixture of backgrounds-- African-American, Asian-American, Caucasian, Hispanic, and Native American.

I like to say to people that MIT students come from the upper left hand corner. Now what do I mean by that? It goes like this-- the faculty and staff who read applications to MIT assign two scores ultimately to each applicant.

One score is quantitative. It's based on grades, SAT scores, rank and class, advanced placement performance and so forth. The second score reflects non-quantitative matters such as essays, initiative, accomplishments, leadership, activities beyond the classroom, community service, high level competitions and so forth.

These two scores establish a matrix. Those in the upper left hand corner of this matrix have done remarkably well in both dimensions. In other words, they're the cream of the crop. MIT students come from the upper left hand corner of that matrix. Our white students come from the upper left hand corner. Our minority students come from the upper left hand corner. They are the best.

The same is true at other highly competitive colleges and universities across the country. We get the right students. But today, let us turn for a moment to the next stage-- academic success of these great students and our responsibility to them.

Here is an undisputed fact-- undisputed, but highly controversial, difficult to interpret, and not discussed. It is clearly summarized in the book, The Shape of the River by Bill Bowan and Derek Bok. That book reports on their study of the academic performance of all students in 28 competitive colleges and research universities across the country. This major study describes the great successes of three decades of affirmative action in higher education.

But it also contains a most troubling finding. Bowen and Bok noted that admission to and graduation from kinds of selective schools included in the study pays off handsomely for individuals of all races and backgrounds. And in some sense, even more importantly, it pays off handsomely to our nation. However, the overall grades of students of color in these schools statistically lagged behind those of other students, even when corrected for factors such as high school grades, SAT scores socioeconomic status, gender, school selectivity, and so forth.

In this statistical analysis of academic performance, there is, of course, a huge individual variation. But the underlying pattern is evident. The findings of the study clearly show that far too many of our minority students are not achieving their full academic potential. This at a time when we need them to be the best as they prepare to be our leaders in this new century of American life.

Now, MIT was not one of the universities included in this study. But we must examine this question in a substantive manner on our campus as well. Our leading colleges and universities enroll enormously gifted minority students. And we need to understand the reasons for the gap between ability and achievement.

It is not helpful, in my view, to immediately retreat to some ideological or political position on any side of this issue. Nor, frankly, do I believe that we should just decide that tests are racially biased and stop at that. We need to understand what's going on. And then we need to roll up our sleeves and go to work on it. After all, at MIT, we're engineers. And we like to think that once we've identified a problem, we've taken the first step toward finding the solution.

And the time to attack tough issues is when we can do so from strength. And we have that strength right now. Our strength derives from the remarkable contributions made by MIT minority students and graduates during the last three or four decades-- to science, engineering, politics, business, community development, and the arts.

Our good colleague Dr. Clarence Williams chronicles many of the contributions of these graduates in two forthcoming books. I have read much of these in draft form, and I can tell you that the achievements of these men and women are truly awe-inspiring. And yet their reflections on their MIT experiences also raise a persistent question. Given the talent and promise of our students and the resources that we devote to developing that talent, have we done, are we doing our best?

As MIT's president, I must listen to, learn from, and act on the constructive criticism that they and many of you have raised with me. And that's what I am attempting to do today. We need to work together to create and sustain a learning environment that brings out the best in all of our students. I can think of no better goal for us as we enter the 21st century.

And I think we must undertake this task with optimism and confidence. Why am I optimistic? Well, just look around this room it's full of remarkable individuals. You just heard from two of them. Students, faculty, staff, administrators, and guests whose achievements and contributions to society are extraordinary. I suspect that right here is the key to enhancing our understanding.

Let us begin by learning what makes for success. Not just thinking about problems. Let us learn from each other's experiences challenges and individual successes. The successful individuals studied by Dr. Williams took personal responsibility for their academic accomplishment, and they took direct advantage of the opportunities afforded by MIT, regardless of obstacles they may have encountered.

Let us, in addition, take community, as well as individual responsibility, for the academic success of every one of our students. There are hints out there about concrete actions that we can take. Let me cite just three examples.

The first has to do with mentoring. One of the crown jewels of MIT's education is UROP, our Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program, which is celebrating today its 30th anniversary. It is a wonderful way for students to get involved in real world class research and to find faculty mentors.

And yet we know that proportionately fewer minority students choose to sign up for UROP. We need to understand why, and then correct it. And we will. Kim Vandiver, our Dean for Undergraduate Research, has made this an important priority. And I'm confident that we can turn it around.

The second example has to do with creating a stronger learning community. People at MIT have always thrived on the intensity of competition and individual achievement. Yet as noted in the report, of our task force on student life and learning, these factors have also led to an environment that is fragmented in many ways. We need to develop community across cultures, across our campus.

One place where this happens is the leadership program now entering its sixth year. Students from an extraordinary array of ethnic and cultural backgrounds spend an intensive week together, getting to know each other and themselves, talking about their aspirations, and developing projects to make those dreams come true. We need to build on the lessons that we are learning from this kind of experience, and make them available to all of our students.

And finally, there's the matter of expectations. We need a community that not only gives members the opportunity to succeed, but that treats all of its members with the assumption that they can and will succeed. And that begins right within each of us. Our expectations of our students and of ourselves must be high.

Over and over on the videotapes, in the Intuitively Obvious series, we hear our students talk about how hard it is to succeed when your teachers or others send you signals that they don't think you have what it takes, when they have lower expectations of you than you have of yourselves. The Committee on Campus Race Relations is now making an updated version of these tapes. Let us learn from our students. It's all right there.

Now I have put this issue of expectations and academic performance on the table, so that we can get to work on it. Over the last few months, I have talked with many of you about our students and how their environment for success can be improved. As a result of these discussions. I want to tell you that I'm in the process of putting together a task force to tackle this head on. It will be results-oriented, and it will have a specific timeline. We will formally announce the group in the near future. And once we do, I will invite all of you to send your ideas, your suggestions our way.

As I said at the beginning, the first step toward a solution is identifying the problem and asking the right questions. I am confident that this place, if any place, can find the solution. By building an MIT that is not only inclusive, but is sustaining, we can take a big step forward, toward creating a better learning and living environment for all of us.

Such a community must be based on equal opportunity, to be sure. And it must continue to be one of supremely ambitious, talented, and hardworking individuals. But it must also be one of mutual respect, of self-confidence, of shared purpose, and of the highest expectations. We owe this to ourselves. We owe it to our students. We owe it to our nation. We owe it to our society. Let us not waver from our collective responsibilities. And let us never waver from our resolute commitment to the dream. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

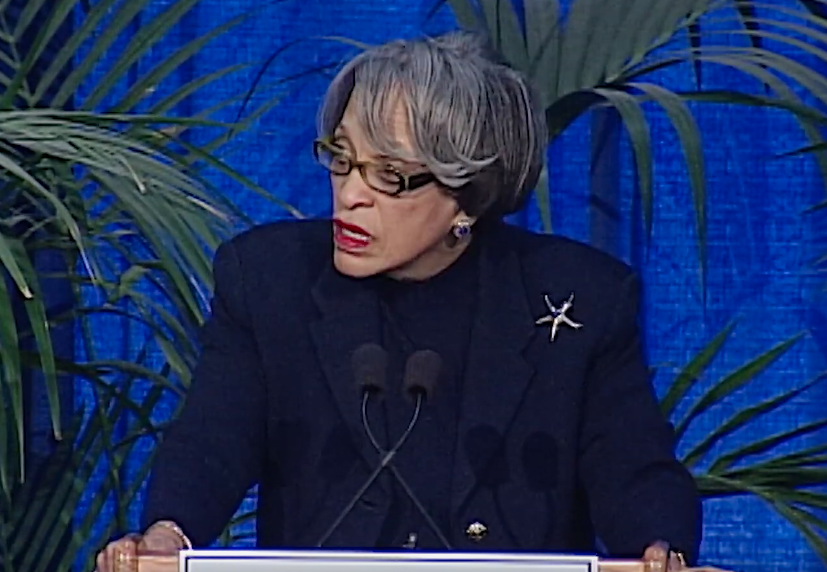

And now it is my privilege-- now it is my privilege to introduce our keynote speaker. From her student days to the present moment, we at MIT have been the beneficiaries of Dr. Shirley Jackson's vision, leadership, tenacity, remarkable coalition building skills, and her wise observations and advice-- always delivered with her characteristic candor.

After graduating from MIT with her doctorate in physics in 1973, she pursued her research interest in nuclear accelerators in this country and abroad before joining Bell Labs in 1976. Uh-oh, Shirley, I said labs instead of laboratories. Inside joke.

In 1991, she became Professor of Physics at Rutgers University while continuing as Distinguished Research Physicist at Bell Labs. In 1995, President Clinton appointed her chair of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. This was a great gain for our nation and a loss for MIT, because she had to take a leave of absence from our corporation, our board of trustees, while she held that high government position.

Last July, as we all know Dr. Jackson's career took another turn, as she assumed the Presidency of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. But we have her back, as a lifetime trustee of MIT.

Now as I said at her inauguration, I've noticed that these days, many university presidents have taken to calling themselves CEOs. Now Shirley Jackson is no CEO. Although believe me, she certainly could be one if that's what she chose. She is a university president in the profound sense of that title. That is to say, she understands at a deep level the essence of universities, the importance of the life of the mind, the goals and aspirations of students, faculty, and staff, and the unique role that the Academy plays in our society. And she will lead accordingly, as she already has, on our campuses, and on the world stage.

Now it is my very great pleasure to present my colleague and dear friend, Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson. Shirley.

[APPLAUSE]

JACKSON: Thank you, Chuck, very much. And good morning. Today, we are celebrating one of the greatest men to ever live, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. King had a tremendous influence on my life. I was a high school student when he delivered his famous I Have a Dream speech. And he was assassinated in my senior year at MIT, which had a lot to do with my decision to remain at MIT as a graduate student. And I think an influence on what has happened to my life since then.

We all know that his dreams and ideals transcend race and time. And his I Have a Dream speech is one of the great speeches in American history. While our opportunities for African-Americans have improved since the untimely death of Dr. King, we by no means have attained his vision of a better world. Prejudice and racism are still thriving in our society. And education is the best way to kill them.

In the past few years, we've seen an African-American man dragged to his death because of his color, dismembered and dismembering his body. A gay man beaten tied to a fence post and left for dead because of his sexual preference. Government workers killed by a man who hated the government and decided to blow up their place of work. And a man so threatened by technology that he sent mail bombs to individuals he felt were furthering its development.

These types of heinous crimes drive the imperative during our celebration of Dr. King's life to rededicate ourselves to working toward his vision for America, for the world.

When I spoke to you, some of you, at this celebration in 1986, I never could have guessed the road that I would be traveling in the ensuing years. While working at AT&T Bell Laboratories, I became involved with issues of science, technology, economy and public policy, and served a number of terms on a variety of state commissions in New Jersey. Then in 1994, I was approached by the Clinton White House about serving as a member and the chairman of the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. And as you know, I served in that capacity from mid-1995 until this past July, when I began my tenure as President of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute or RPI.

Being the chairman of the NRC, as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is called, was truly an honor and an awesome responsibility. In that role, I oversaw the development of policies to ensure the protection of the public health and safety, the common defense and security, and the environment in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy and nuclear materials in the United States.

I also had the responsibility to ensure that the NRC staff carried out these policies in accordance with statutory requirements. As you might imagine, I interacted daily with government officials scientists and engineers from around the world, as well as with the White House, the Congress, and public policymakers in Washington DC.

One of the most enjoyable parts of my job was representing the government of the United States at various international bilateral and multilateral meetings and commissions. Knowing that the policies that I helped develop influence international nuclear safety and nuclear nonproliferation was heady, yet sobering.

Despite the gravity of my position, I have to tell you I could not help smiling from time to time as I traveled internationally. Because I realized that Dr. King would have been proud that the face representing the United States at major nuclear meetings and summits around the world was black and female.

His activism and leadership surely made a difference. Yet there is still much to be done. Others have given testimony to that this morning. When I last spoke to you in 1986, MIT enrolled approximately 300 African-American students. Last year, MIT enrolled 348 African-American students. In 1986, there were 14 African-American faculty members. Today, there are 25.

While these numbers are improvements, they are not enough. But MIT is not alone. I could tell you worse statistics about the institution I lead. Minority representation in science and engineering is embarrassingly low across the country. This issue has been discussed continuously for 15 years, but little has actually changed.

And there's evidence, at least with respect to African-American males, that the situation is worsening. A particularly troubling statistic concerns the numbers of African-American students who are completing four or more years of college. According to the US Census Bureau in 1985, only 59.8% of black students completed high school. In 1997, that number had jumped to 74.9% graduating. Despite this marked increase, the number of students going on to complete four years of college only increased 2%, from 11.1% to 13.3%.

This situation is a larger problem than merely increasing the number of African-American students enrolled in engineering and science fields. We all must work to increase the number of African-American students, especially African-American males attending and graduating from institutions of higher education.

Interestingly enough, whether our students like it or not-- although I'm sure the students here recognize it-- serving as role models is important for each of them, and one often overlooked. Because of the influence of the media, our young people often look toward role models and heroes from pop culture and athletics. While there are worthy individuals among these ranks, they cannot be the only possible candidates to which our youth look.

We need young people to see role models of color in corporate America, in academia, and in government. Which means that we must push our current minority students to help accomplish this. We as leaders must explain to our students the important role they play in diversifying all sectors of our society, and the impact that fact will have on the next generation.

That means imposing demanding standards of excellence and achievement, even as we strive to create more community in the higher education institutions in which they study. We need high achieving minority, especially African-American, Hispanic, and Native American scientists and engineers, professors, corporate leaders, entrepreneurs, and government officials to expand the vision of our young people of what they too can accomplish.

Because of the progress that has been made since the 1960s, we have more role models in the professional ranks than ever before. Women, for example, are finally moving into the highest ranks of corporate America, including the first CEO of a Dow 30 company, Carly Fiorina of Hewlett Packard. And women have led the successes of newer companies that have become household names. Meg Whitman has built eBay into an overnight success story, and Joy Covey is currently the chief strategist behind Amazon.com. In fact, two of the three largest US banks have female finance chiefs-- Tina Dublin of Chase Manhattan and Heidi Miller at Citigroup.

African-Americans also are finally appearing in boardrooms and at the executive level in corporate America and in government. Franklin Raines is the former director of the Office of Management and Budget, and currently is the CEO of Fannie Mae. In Silicon Valley, John Thompson is president and CEO of software manufacturer Symantec. The current United States Secretary of Labor is Alexis Herman and the Secretary of Transportation is Rodney Slater. And I could cite a few more.

And while these and other successes are an improvement, we have a long way to go before the corporate executive ranks and high level public policy positions are representative of the face of America. For that matter, the road to travel to executive leadership in academia also is long, although progress is being made.

While women presidents of higher education institutions may not be commonplace across the country, especially when one looks at African-American females, they are actually in the capital district, in the Albany region. In fact, four of my colleagues at neighboring colleges and universities are women-- at Skidmore College, the Sage Colleges, Empire State College, and SUNY at Albany.

However, our numbers are few. According to the 1999 Chronicle of Higher Education Almanac, the most recent data from 1995 showed only 16.5% of college presidents were females. It also stated that approximately 10% of the presidents belong to a minority. And 5.9% were African-American.

Actually, the diversity among faculty ranks is even worse. Only 3.2% of all full time professorships are held by African-Americans. The number is 5,240 out of 163,632. I always say you have to look at the numerator and the denominator. This fact is not just appalling, it is unacceptable.

Leaders in higher education, then, must take a bold approach toward effecting the change needed to correct this situation. Americans look to institutions of higher education for leadership in a variety of areas, including the production of future leaders.

To be effective, then, we in leadership positions must look introspectively, at our own leadership qualities and abilities, and at our own institutions. Are we living the gospel we preach? Are we talking about the changes that need to be made? And are we rolling up our sleeves and effecting those changes? Are we developing programs to promote diversity while also working to diversify our own workforce? Are we looking at our current structures and programs to see if they can meet the needs of the student body we want to attract and retain?

We need to ask ourselves these questions and more. We cannot expect more of our students than we ask of ourselves. The American system of higher education is lauded around the world. Partly because of its independent nature. Each school within broad statutory regulatory or accreditation guidelines is autonomous to create its own policies, curriculum, and standards. This model gives us a great advantage to adapt to the needs of the country.

However, as leaders, we must be willing to take on the challenge of doing so. Change does not come very easily, especially in academia. The traditions of the ivory tower are very strong. But as Dr. Robert Jarvic-- you know who he was? He was one of the first designers of artificial hearts. And he said the following-- leaders are visionaries with a poorly developed sense of fear. And no concept of the odds against him. They make the impossible happen.

At Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, I have begun a process-- the development of the Rensselaer plan. Now, this plan will be a blueprint for the future, identifying the direction in which we need to travel to achieve a position of prominence in the 21st century as a world class technological research university with global reach and global impact.

The Rensselaer plan will take shape from three informing principles-- excellence, leadership, and community. The process is still underway. But it has been enlightening, and enlivening for all involved. Students, faculty, staff, and alumni have all made contributions during the public comment period. We posted it on the web. That just ended. The next draft is being completed, and will undergo another review. I plan to present the final plan to our trustees in May.

Two core tenants of the Rensselaer plan are diversity and community. Or comm-university, as I like to call it. To be competitive in the 21st century, our universities, our PI, must reflect the society we hope to serve and lead. And we must develop multicultural awareness among our students. Recognizing this fact, I have insisted that diversity be a major tenant of our plan.

You know, technological advances have made our world smaller than ever. Things we consider passe and almost obsolete today-- the calculator, tape players, and TV dinners were great advances 20 years ago. Now, our students have the ability to instantly communicate with someone sitting at a computer on the other side of the world.

Most of us have concentrated our efforts towards giving our students the technological tools they will need to be competitive in the computer age. However, we have often overlooked the importance in their future success of their ability to deal with change and diversity. Having a diverse student body is one way to assist our students in this area.

Diversity at Rensselaer and in the Rensselaer context has four elements-- geographic diversity, intellectual diversity, gender diversity, and ethnic diversity. Tolerance and communiversity will make it all work. Communiversity refers to the university as a community, as a family. It also is meant to describe the fact that the university is part of the city. The town, indeed, the larger society of which it is apart. Members, then, of the communiversity can and should work to ensure the viability and vibrancy of their shared community.

Traditionally, institutions of higher education have used their admissions policies to ensure the diversity of their student bodies. During the past few years, however, affirmative action and the college admissions process have been under intense scrutiny and attack. The usefulness and fairness of affirmative action practices have been debated both publicly and behind closed doors.

We must read the same thing. In their book, The Shape of the River, William Bowen and Derek Bok took a systematic look at race-based admissions policies and affirmative action at a carefully chosen group of selective admissions colleges and universities. And at the subsequent successes of their alumni, in their summary they concluded, and I quote, substantial additional benefits accrue to society at large through the leadership and civic participation of the graduates, and through the broad contributions that the schools themselves make to the goals of a democratic society. In other words, higher education administrators and public policy decision-makers must recognize the importance of minority graduates and the importance that they play in the larger American society.

Now, let me talk specifically about science, technology, and engineering. Because much attention has been paid to issues of underrepresented minorities and women in these arenas. Unfortunately, as I said earlier, all the discussions have done little to change reality.

To make any real difference, I believe we truly have to try a more holistic approach. We cannot merely focus on the students who are getting ready to apply to college. We must look at the system in which they are being educated. Currently, many of us in universities are seeking out those underrepresented students whom we believe can succeed.

But we also must begin to create opportunities at an earlier stage, for those students who may not recognize their potential for success. This pipeline needs to be fully developed and supported by the universities, local communities, industries, and school districts. A full pipeline depends upon key points of intervention along the way. These interventions must address the achievement gap of African-Americans and other underrepresented minorities, when compared by conventional measures with their white and Asian counterparts.

Yes, I'm talking about testing results, and sometimes actual achievement in college. Now before all of you fall out of your seats, let me say that while I do not believe that SATs or any test scores give the full measure of the individual-- and while I certainly agree with William Bowen and Derek Bok about the societal benefits of successful graduates of selective institutions, MIT and Rensselaer among them-- I also know that the achievement gap is a nagging concern that threatens to undermine the continued and needed expanded opportunities for underrepresented minorities in these institutions. It also threatens to undermine the confidence of these very same students.

That means we must look at the institutions themselves, and we must look at the pipe through which they come. Competitive institutions have cultures that tend to view excellence and caring as an oxymoron. But this isn't so. If we admit the best students, we cannot squander the talent. If we admit the best students, we cannot squander the talent. We must have an equal commitment as universities to their academic and life success.

My son is a freshman in college, is a freshman at Dartmouth. And I know that the four years between high school and college graduation are key years in the development of a successful adult. And in their view, of their Alma mater, once they've graduated. An expectation of excellence and a nurturing of that excellence go hand in hand. This is the standard at Rensselaer, especially with our undergraduates.

But the standard can not disappear, as it often does, when we go beyond majority and-or male students. This is the challenge we face. To walk that talk with all of our students. Universities, especially highly selective ones, must take a more activist role in pre-college education.

Let me tell you about an example at Rensselaer about which I am very excited. It's called Project Raise-- the Rensselaer alliance to increase student excellence. More than 900 low income students from the local area will receive advanced instruction in algebra, chemistry, physics, and trigonometry, beginning in the seventh grade, and continuing through high school. This ambitious effort also will involve mentoring and financial planning for the students and their parents.

While this activity only recently got underway, it recognizes that preparation to enter scientific and technological careers is a cumulative process. One cannot aspire to be a scientist, an engineer, an entrepreneur, or technological leader, without a grounding in calculus. But one cannot do calculus if one cannot add, subtract, multiply, and divide. And if one cannot do geometry, trigonometry, and algebra. But the learning also depends upon incentives to the students and the understanding of their parents. Project Raise tries to build these factors into the program.

Higher education also must take a more active role in the professional development and continuing education of outstanding primary and secondary school science and math teachers. It's interesting, because when we were in the university, most any administrator will tell you that the core, the key to the excellence of the university, aside from the students it attracts-- and what allows them to attract those students is the faculty.

But when we look into the pre-college arena, we sometimes seem to lose sight of that fact. But who better to identify future successful students than their teachers? And who is in a better role to interest students in the opportunities in mathematics based and scientific fields than these teachers?

So universities in corporate America need to develop sustaining partnerships and programs to make teaching attractive to talented individuals in mathematics, science and engineering. Who are actually trained in these fields to expose these teachers to the latest innovations and research currently being conducted.

The fields that I'm talking about are changing so rapidly that we cannot expect teachers educated even five and certainly 10 years ago to have any grasp of the current innovations and cutting edge technologies. Teachers need the opportunities to work as part of their contracts, on a continuing multi-year basis as partners and innovation. And as researchers, alongside colleagues in the industries and in the universities.

And I intend to do this at Rensselaer. Teachers can then take their professional experiences back to the classroom, and share them with their students. And I'm not talking about the one time summer program. I'm talking about an actual career path, where working in the university and working in the local industries is an actual part of those s' contracts.

The enthusiasm and the excitement, the teachers develop through their own relevant experiences will translate into more vibrant and exciting classes for their students. Because excitement is contagious. And I have no doubt that it will influence some students who may never before have considered a career in science, mathematics or engineering.

We also must take a look at how we are preparing our current college student body to become successful alumni. Are we preparing them only to be successful scientists and engineers? Or are we also preparing them to be informed and participatory members of our society?

These issues go hand in hand. And when I was a student, I was admonished many times about doing something other than my studies. But how we prepare our students to succeed in an increasingly complex and global economy-- it's going to be hard to do.

If they have no idea how to deal with the real diversity and complexity of the global workforce-- indeed, if they do not value it and embrace it, higher education must then offer students the opportunity to explore the entire universe around them. Not just the universe of their fields of study. A concomitant challenge is to make communiversity a daily reality.

This means not only fostering community within the campus, but to provide opportunity beyond the campus, perhaps as part of the structured curriculum. For our students to collaborate with the larger community, to improve the quality of life experience that redounds to the benefit of all. This can be local. It can be at remote locations. Or even through virtual interactions. And we're experimenting with these ideas and their combination at Rensselaer.

Now, I remember how easy it is-- and as I say, I was admonished anyway-- to get caught up in one's studies. Now, I was very serious about my work. And that always came first. The pressure on students to be successful is very large. Yet, I also remember that some of the greatest lessons of life I learned while attending MIT did not happen on the campus.

They happened when I was volunteering in the pediatric ward at Boston City Hospital, or tutoring at the Roxbury Y. Or planning an event for my sorority, Delta Sigma Theta. Those lessons-- the lessons of humanity and humility, of organization, of realizing that another's struggles can be greater than one's own, helped me to become a better human being. And consequently, have contributed to the successes that I have achieved.

Research institutions like MIT and RPI have an added duty to fulfill these needs because of the professional successes of our alumni. We should not only be creating leaders in engineering and science. We need to be creating role models for others to emulate. Paul D Schaefer said quite aptly, the most important single influence in the life of a person is another person who is worthy of emulation.

As administrators, we have to keep this fact in mind at all times. We must create opportunities for our students to be engaged in realms beyond their studies and in realms that enrich their studies. And to help them develop into confident, high achieving, well-rounded, mature role models for the next generation of students.

Finally, let me speak to leadership on a personal level. I firmly believe that we who are in leadership positions must set personal examples of commitment, hard work, adherence to high ethical standards, and the courage to take on the status quo, in how we shape our own institutions, and in how we speak to the larger society. Taking on these challenges is not easy. But they must happen.

In What Manner of Man, Dr. King wrote, the function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character-- that is the goal of true education. Those were Dr. King's words. By creating an atmosphere in which our students can be and must be academically challenged with an expectation of excellence, while learning to embrace and celebrate diversity, to explore broader cultural and intellectual interests, to become confident we can positively influence an entire generation of Americans-- that is the goal to which we all must aspire and to which we dedicate ourselves as leaders and as role models.

I like to paraphrase in a different way a quote from a famous movie. And it simply is, leadership is as leadership does. Then and only then will we be creating the world of which Dr. King dreamed. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

MERRITT: Now I have the honor of introducing Chancellor Lawrence S Bacow. Chancellor Bacow will present the 1999-2000 Martin Luther King Junior Leadership Awards.

BACOW: Thank you very much, Carla. It is a distinct honor and pleasure to have the opportunity today to present these awards. Today, we gather to celebrate the life of a true American hero. And I can think of no better way to do so than to recognize and honor those among us who best exemplify his principles, his ideals, and his dreams.

Indeed, the students faculty, and alumni that we recognize today are in many ways heroes in their own right. They have shown us each the path-- the path to the dream. And I think in doing so, if I may, also represent a concept which is embodied in the ancient Hebrew text, the Talmud. Which speaks to the obligation of tikkun olam-- the obligation for each and every citizen to try and repair the world. And I think each of the three people that we recognize today, in their own way, has done so.

I'd like to call upon our first awardees to come up-- Professor Rafael Bras.

[APPLAUSE]

In his letter of nomination, Mr. Joel Rivera, President of the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers, cited your inspirational and steadfast commitment to underrepresented students at MIT. During the past 24 years, Rafael, your achievements at the institute as student, faculty member, department head, program director, and advisor have motivated and encouraged countless young people from all backgrounds.

While ceaselessly contributing to the field of hydrology and hydro climatology, you have never lost sight of those who wish to follow in your footsteps. Whether serving as director of the MITES program, or successfully recruiting Hispanic faculty to MIT, you have embodied Dr. King's vision, by generously and selflessly working to provide better opportunities for those who have been denied. As Mr. Rivera aptly stated, you are always encouraging minorities to achieve their best.

Rafael is one of our great scientists at MIT, a wonderful teacher, a terrific department head, an outstanding colleague, and I have to also add, a distinguished member of the class of 1972, my class. Rafael, congratulations.

[APPLAUSE]

BRAS: Thank you very much, Larry. Indeed, the class of '72 is unique. There is a tradition in my family. Every year, the weekend of Martin Luther King Day, we go skiing in New Hampshire. It is always a wonderful time shared with our closest friends.

Driving back in the evening that Monday, we always listen-- and I hope you all do-- to Eric in the Evening, which is a jazz program in public radio. In the last few years, host Eric Jackson entertained us by skillfully alternating music with the speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King.

It is truly amazing how a van full of 15-year-old boys falls silent at the cadence of Dr. King's incomparable style. I wish, I only wish I had that power of oratory. If anything, I could keep the children quiet.

In one of the speeches played this year, Dr. King hammered on the advice of an older woman. And it went something like this-- when in doubt, when you have self-doubt, when things are not going right, always have faith God will help. I like to say that the more recent version of that, if anybody has seen the movie Fields of Dreams-- build it, they will come.

Life is full of challenges to that faith. I see the nation playing political football with a six-year-old. While it turns back, at the same time, 400 desperate Haitians, including men, women, and children. I think where most all of us have faith that ultimately rationality will prevail, as Dr. Vest stated, and Dr. Jackson also alluded to, I see affirmative action being dismantled. I must have faith that men and women of goodwill will stop the inevitable damage that we see already.

Sometimes, more often than I would like, I see lack of civility, unacceptable behavior among us. I wonder where this may lead us. But again, I must have faith that reason will keep us focused on our mission.

And sometimes, yes, I catch myself being unkind to others. I find myself being caught in the current, trying to rationalize what I really know, things that are not correct. I find myself forgetting the important things in life.

At that point, though, faith is not enough. I know that is really up to me and only me to make it right. Maybe that is what faith is all about. Hoping that all individuals, flawed as we are all, take responsibility, correct our mistakes, deal with our problems, and act with honesty.

Let me end by simply thanking you for honoring me. I am really humbled. Thank you, MIT. Thank you, the committee for my selection. And thank you for the Society of Professional Hispanic Engineers for the nomination. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

BACOW: Thank you very much, Rafael. I'd now like to call upon our next awardee, Dr. Woodrow Whitlow to come up.

[APPLAUSE]

Dr. Whitlow has the distinction of having three degrees from MIT. Our program only notes one. But, in fact, there are three, all from Core 16. He is currently the Director of Research and Technology at the Glenn Research Center of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in Cleveland, Ohio, having spent the earlier part of his career at NASA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

In his letter of nomination of Dr. Whitlow, professor Wesley Harris cited his invaluable commitment to furthering our nation's science and technology goals by developing unique research programs that create partnerships between NASA centers, US industry, and historically black colleges and universities.

As a scientist, director, graduate thesis advisor, and a professor at majority institutions and at Hampton University, your endeavors and distinguished accomplishments are consistent with Dr. King's ideals. The members of the Martin Luther King committee strongly believe that your efforts are a fitting tribute to his vision, and of full inclusion for every person in our society. And that they will make this a land where all talent is nurtured and valued.

In addition to being an extraordinary leader in his own right, a distinguished alumnus of MIT, I'm also pleased to note that Dr. Whitlow is a fellow member almost of the class of '72-- '74. And a fellow Detroiter. Congratulations.

[APPLAUSE]

WHITLOW: Thank you. I remember back in the early 60s, going to downtown Detroit with my mother and father. They took me to march with Dr. King, back in the days when he was telling us about his dream for an America that included the contributions of everybody.

With the opportunity that I had to come to MIT, I had a chance to realize my dream-- almost-- of becoming an astronaut. Because I thought that the way you did that was you came to MIT and you majored in aeronautics and astronomics. Then you went on NASA and then you became an astronaut. It was a very simple process.

However, I got slightly detoured. But I've never ever doubted my decision. After leaving MIT, the things that I picked up here, and particularly recognizing that one of the major reasons that I had the opportunity to pursue that dream was due to the efforts of our keynote speaker, Dr. Shirley Jackson. Who at the time we said was only a graduate student, was striked more fear into the hearts of us than any professor ever could.

So I would again like to thank Shirley Jackson for--

[APPLAUSE]

--for her efforts on the cause on behalf of our students-- in fact, most students that have come since her-- and the contributions that she's making to society.

I've always thought that it was required to give something back. To help as many people as I could. If that only included one, that would be appropriate. I would like to think that I've been able to pursue and help realize Dr. King's dreams with the efforts that I've made.

At the Glenn Research Center, we have four key values-- quality, openness, integrity and diversity. Diversity being to value the contributions of everyone and inclusion of everyone. And that includes not just African-Americans or Hispanics or Asians, but also those of non-minority population.

I would like to thank the nomination committee, the selection committee. I'd like to thank Dr. West Harris, who I don't think was able to be here today. Most people don't know that I was West's first PhD student. He's been a big influence on my life, big friend of my life. And I continue to value his friendship.

I would also like to dedicate this award to my mother and especially to my father, who missed seeing me receive this award by about two months. So I would like to dedicate this award in his memory. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

BACOW: Thank you, Dr. Whitlow. Our next recipient is to Ticora Jones. Ticora, please come up.

[APPLAUSE]

It is often said that if you have a difficult job to do, give it to a busy person. And in looking over Ticora's resume, I am astounded. She has managed to accomplish great things and to do many things during her time here at MIT. A member of the class of 2000, she is majoring in material sciences and engineering. She has found time to work at the IBM Research Center, to be a teaching assistant in organic chemistry, to do to work in the MIT second summer program. She's managed to travel to Sweden to work at the Royal Institute of Technology. She has assisted Dean Osgood and others in the Office of Minority Education. I could go on.

Our students-- MIT is a great place largely because we get great students. And Ticora is a wonderful example. I would like to read from the letter which Ticora received, in which she was named a Martin Luther King Leadership Award recipient. In his letter of nomination, Dr. Douglas Matson of the department of material sciences and engineering cited you as an exceptionally resourceful and natural leader, who has demonstrated constrict considerable strength as a contributor to MIT. Your ability to motivate others enabled a group of talented individuals to develop and successfully complete a project with multiple interrelated tasks. The efforts of your classmates resulted not only in an outstanding product, but also in a deeper appreciation for what can be accomplished by a skillfully directed team. The sign of a true leader.

A commitment to achieving the best is evident in your work as Vice Chair of the Undergraduate Association Finance Board, and as co-founder of the Black Women's Alliance at MIT. As the Office of Minority Education tutor of the year, you have distinguished yourself as one who is dedicated to the highest academic standards.

The members of the Martin Luther King committee believe that you have embraced the essence of what Dr. King demanded of himself and others. And your endeavors are a tribute to his dream. Ticora, congratulations.

[APPLAUSE]

JONES: Thank you. Good morning. As I look back and reflect on what the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr has meant to me, I must say that I am very thankful to be alive and a student in these times of advancement and technology, and to be a black woman engineer in what seems as-- is the world is my oyster.

The words, "to whom much is given, much is required" come to mind as I thought of how to express my appreciation for this moment. Dr. King was given the challenge of leading a civil rights movement that changed the shape of what America is, pushing it towards what it could be. Though our challenges as students may not be as arduous, we still must rise above the expectations, and help those around us to meet their goals in this new millennium.

At times, things are hard. But I must take the time to say thank you. To my parents for their examples of excellence, their love and support that has guided me along this path of life. To my grandparents, whose hard work and dedication has given me the spirit to persevere. To my extended family for their open arms and hearts. And to my MIT family-- administrators, mentors, professors, friends, and my BWA sisters, whose hard work, advice, love, smiles have just brightened so many days.

Finally, I would like to extend my thanks to the MLK committee for this wonderful moment, to all of you for coming out bright and early this morning. And I will cherish this moment always. Finally to my fellow students-- to whom much is given, much is required. Let us lead by example, indeed. And to this new millennium-- the world is ours. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

BACOW: Let me just, before I turn it back to Carla, close by saying that while both Dr. Jackson and Dr. Vest have both observed that the dream is not yet realized, I think based upon the three awardees that we have recognized today, we can see that our future is very bright. Thank you all.

[APPLAUSE]

MERRITT: Thank you very much, and congratulations to all the award recipients. And now it's my pleasure to introduce Provost Robert A Brown. Provost Brown will recognize the 1999-2000 Martin Luther King Jr visiting professors.

BROWN: Thank you, Carla. As Shirley reminded us this morning, Dr. King challenged us in many ways. And one of his most important challenges was to celebrate cultural diversity. It's my pleasure this morning to tell you about our continuing commitment to this effort on the MIT campus. And one of the crown jewels of this effort is the MLK Visiting Professor Program that was begun in 1995.

Its objective is to bring to MIT outstanding scholars to participate in teaching and research, and to enrich our community. Appointments to the MLK Visiting Professor Program are made upon recommendations from academic departments, and come from all parts of MIT. This year we have eight MLK visiting professors with us.

I'd like to take the opportunity to recognize two individuals who were with us this morning. The first is Ms. Karen Lacy. Karen is a visiting lecturer in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at Harvard University. She has research interests in the suburbanization of middle class blacks in the United States. At MIT, she's teaching two courses in the housing and community economic development group within DUSP.

Now, Karen was with us sitting next to me at the early part of the breakfast. She had to leave to participate in the honorable profession of teaching a 9 o'clock class.

The second member of the MLK program with us this morning is Professor Arthur Mutambara. Professor Mutambara has a PhD from Oxford University, and is visiting the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at MIT. He's currently on the faculty of the mechanical engineering department at FAMU FSU College of Engineering in Tallahassee, Florida.

His research is very interdisciplinary. It can be characterized as a combination of mechatronics and robotics. And at MIT, he's interacting with groups across several laboratories and centers, including the space systems laboratory, the information and control engineering group within the aero-astro department, and LIDS, the Laboratory for Information Decision Systems.

His research covers programs that the fusion-- multi-sensor fusion, working with distributed satellite systems, satellite orientations robotics, and mechatronics. As part of his educational contributions at MIT, Professor Mutambara will give a series of lectures in a course being co-taught between aero-astro and mechanical engineering. Professor Mutambara, will you stand up please? Welcome.

[APPLAUSE]

Our other six MLK visiting professors could not be with us this morning. They're listed in the green program. One of the things that I think is most exciting this year is the fact that they cover such a multidisciplinary mix. We have people that have been with us in performing arts, urban studies, an engineer-- a number of different disciplines in engineering. Really has enriched MIT greatly.

For all of my faculty colleagues in the audience, please take this to heart, and nominate more people for next year. We can never have enough visitors. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

MERRITT: We will now continue with some announcements that are relevant to our celebration. I would like to announce that the Martin Luther King Jr committee presents the student dedication to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. There is an installation design at 12 noon in lobby 10 titled The Struggle Continues. This installation was completed by a group of students over IEP. The consecration ministries will perform at 4:30 in lobby 7, followed by the South Central Mass Choir performing at 5 PM, also in lobby 7.

In addition, on Saturday, February 5 from 9 AM to 3 PM, the annual Martin Luther King Jr MIT Center for reflective practice youth conference presents Community Justice-- Environmental, Economic, Social, And Political Empowerment. This event will be held at the MIT Stretton Student Center on the third floor. For more information, please contact Marie Colbert at 253-3216. Or you can email her at mcolbert@MIT.edu.

Now, I'd like to ask Reverend Jane Gould to come forward to give the benediction to close this morning's program.

GOULD: As a community, we seek individual and institutional transformation. Dr. Shirley Jackson, Professor Raphael Bras, Dr. Woodrow Whitlow, Ticora Jones, Ibrahim Fontaine, Tamara Williams, and Carla Merritt-- witness to the possibility of bold, connective and transformative leadership, for MIT, the nation, and the world.

Retired archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa and chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Desmond Tutu once prayed, Lord, where I am wrong, make me willing to change. Where I am right, make me easier to live with. May we take the words of Tutu to heart, as we go forth from this place to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with our God. Amen.

MERRITT: I hope that everyone has enjoyed this morning's program. It has been a wonderful event, which I'm sure we'll all remember for a long time. Thank you for coming, and I hope to see you at next year's breakfast. This concludes our 26th annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr celebration. Goodbye.

[APPLAUSE]