Wasserman Contemporary Art Forum, "The University as Patron of Cutting-Edge Architecture” (5/8/2004)

[LOGO MUSIC]

FARBER: Good morning. Hello. We were just waiting for some people to come over from the overflow simulcast, but I think we'll go ahead and begin. Good morning again.

My name is Jane Farber. I'm the director of the List Visual Arts Center here at MIT, and it's my very great pleasure to welcome you to the List Center's annual Max Wasserman Forum on Contemporary Art.

As you know, this year's topic is "The University as Patron of Cutting-Edge Architecture." Just a few words about the forum-- the annual Max Wasserman Forum on Contemporary Art was established in memory of Max Wasserman, who was an MIT class of 1935 and who was a founding member of the MIT Council for the Arts. This public forum addresses critical issues in contemporary art and culture through the participation of renowned scholars, artists, and arts professionals. We are extremely grateful to Jeanne Wasserman for her continued generous support of this project and for being such an absolutely superb member of our advisory council. Thank you so much, Jeanne, for everything.

[APPLAUSE]

And thank you to Peter Wasserman too for all of your help with this year's forum and also to the members of the Wasserman Forum Committee-- Jennie [? Frucci, ?] Bill Arning, Andrea Miller Keller, Jerry Friedman, Dorothy and Roy Levine, Marjorie Jacobson, and special thanks also to Allen Brody, Associate Provost for the Arts, here at MIT. I think I just changed somebody's screen. Sorry.

Also I would like to especially thank William Jay Mitchell, who is the Academic Head of Media Arts and Sciences here at MIT for his generous collaboration with us on this project. It wouldn't have been possible without him. And I must give my very, very sincere thanks to the List Center's staff. They've just done an amazing job on this project, and I'd like to recognize especially David Frylock, Bill Arning, [INAUDIBLE] Kikuchi, Barbara Pine, and Camillo Alvarez, as well as the many volunteers, all these nice people in yellow t-shirts, who have given their time to help this happen this morning.

Before I introduce our forum participants, I'd like to make just a few brief more announcements. There will not be a reception following this event, but at 4:00 PM today at Simmons Hall on Vassar Street. There will be the dedication of a new work by Dan Graham in Simmons Hall, and we would like to invite you all to be present for the dedication of his Yin/Yang Pavilion.

So a campus map is included in your package. Whoops. It looks like this, and Simmons is marked there with a red number 2, so you can find it. And we hope you'll use this map in the interim to guide you around campus, if you'd like to see some of the other public art and projects on campus. And also on the back, there is a list of restaurants, if you would like to have lunch in the area. So we hope you'll find that helpful.

And I'm sure many of you want to take a tour of Frank Gehry's Stata Center. And you can do this at an open house on May 24. Please go to the web at mit.edu/evolving/ for more information on that. And tours of Steven Hall's Simmons Hall can be arranged through Simmons Hall, so you need to email a request for a tour to simtoursrequest@mit.edu. The people in the yellow t-shirts can give you this information if you missed it.

And also we hope you'll have a chance to visit the List Center at 20 Ames Street, as there are two remarkable exhibitions currently on there, Marjetica Potrc's "Urgent Architecture," and the first US solo show of Warsaw-based artist, [INAUDIBLE]. And on view and in our Media Test Wall is Amy Globus' video, electric sheep. This lecture is being recorded for archival purposes and will be webcast on the MIT world website. So if you missed something today, you can revisit the forum at the website in the future.

We apologize to the many whom we're not able to accommodate in this auditorium, and hello to those of you watching the simulcast in 10-250. We appreciate your patience and your understanding. And finally, we're very lucky that the remarkable individuals who are here today were able to take time out of their very busy schedules to be with us. So they will need to leave the auditorium immediately after the forum. So we regret that they won't be able to stay around and converse with you. We hope you'll understand.

Finally, I truly regret to inform you that there's a change in today's forum. Steven Holl has back trouble and will not be able to join us. We're very, very disappointed. He had hoped he would be able to come, but after an MRI and the doctor's advice, he wasn't able to join us. So we wish him well and hope he's well soon, and we're very sorry that he can't be here today.

But we have wonderful participants today. Our participants are architects Frank Gehry and Robert Venturi, architectural historians and theoreticians James Ackerman, Kimberly Alexander, and Kyong Park, MIT President Charles Vest, Executive President John Curry, and William Mitchell, who is head of the program in Media and Arts and Sciences at MIT. He will be serving as moderator.

If I can just give you some brief biographical information about our panelists, then we can begin. James Ackerman is an architectural historian and the 2001 winner of the prestigious Balzan Prize for History of Architecture. His work Palladio has had immense influence due to its innovative way of examining patronage and the role of the works commissioner in creating cultural significance for architecture. James Ackerman's talk will provide context for the forum's discussion of current university buildings within a historical perspective.

Kimberly Alexander is an architectural historian who blends social history perspective in her work with the built environment. She was the first curator of architecture and design at MIT, a post that she held for 10 years, during which she organized significant exhibitions on MIT's great buildings, such as Alvar Aalto's Baker House and William Welles Bosworth's 1916 master MIT campus plan. She will discuss MIT's particular role as a patron of architecture.

Frank Gehry, as I'm sure you all know, is the designer of MIT's new Ray and Marie Stata Center as well as the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and many, many others. His buildings have received over 100 national and regional AIA awards, including the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1989, the premiere accolade of the field, and many more too numerous to mention.

William J. Mitchell is Academic Head of Media Arts and Sciences and Professor of Architecture in Media Arts. And he was the former Dean of Architecture at MIT. He also serves as Architectural Advisor to the President of MIT. His recent publications include Me++: The Cyborg Self and the Network City, e-topia: Urban Life, Jim-- But Not As We Know It, and City of Bits: Space, Place, and the Infobahn.

Robert Venturi's extension commissions, as well as his teaching, advising, writing, and lectures, have received national and international attention. His major campus buildings include five at Princeton University, three at Dartmouth, and five at the University of Pennsylvania. Robert Venturi's numerous awards include the Republic of Italy's Commendatore of the Order of Merit. He's gotten the Presidential National Medal for the Arts, and he also was a recipient of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize.

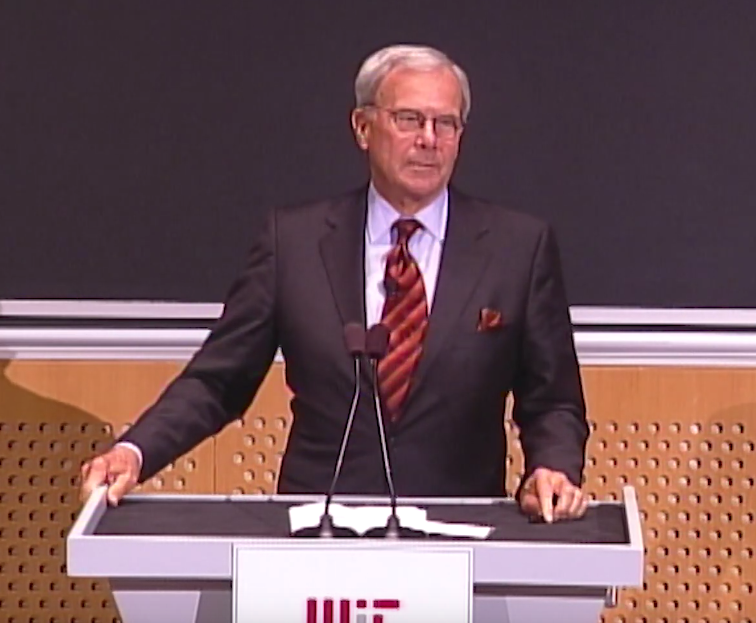

Charles Vest has been president of MIT since 1990. He holds degrees from West Virginia University, the University of Michigan. He chairs the US Department of Energy Task Force on the Future of Science Programs. And he's the Vice Chair of the Council on Competitiveness and the past chair of the Association of American Universities. And he's now serving as a member of the Commission of the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction. He's also leaving us, so we are truly sad about that, because he's been a fabulous, fabulous president.

Respondents for today are MIT Executive Vice President John Curry and artist, curator, and architectural theoretician Kyong Park. John Curry, MIT Executive Vice President, was formerly Vice President for Business and Finance and Chief Financial Officer at the California Institute of Technology. He was also administrative Vice Chancellor and Chief Financial Officer of the University of California in Los Angeles. He's authored numerous articles on academic finances and management, and he's a trustee of the National Association of Colleges and University Business Officers and a trustee and chair of the Finance Committee of the College Board.

Kyong Park is my friend and founder-director of the International Center for Urban Ecology in Detroit and New York City. And he was the founding director of the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York. He was also commissioner for the international section of the Kwangju Biennale in Korea in 1997, where he organized a wonderful architectural show called "Images of the Future: The Architecture of a New Geography."

Finally, there will be a 15-minute intermission following President Vest's presentation. So without further ado, if you would join me in welcoming James Ackerman, who will make our first presentation.

[APPLAUSE]

ACKERMAN: May I remove the PowerPoint? Could I get the PowerPoint out of the way, because I have to put my notes down. I'd like somebody else to do it.

Good morning. I'm honored to be initiating this very promising colloquium, and I want to add to the expressions of thanks that were delivered by the director of the List Center my own warm feelings of gratitude towards Jeanne Wasserman, who's been a colleague of mine over many years. My talk is divided into two parts. The first part has to do with the organization of university environments, and the second address is the growth of the phenomenon of what might be called the signature building, which is the primary subject of the discussion today.

Here we see together an instance of early campus organization in the late 17th and early 18th century. We have William and Mary on the left and Harvard on the right. Let me emphasize that these were colleges with very limited aims at the beginning. It was characteristic in early building of the kind to join together residents with classrooms and other functions of the college. And in both of these cases, the project was conceived in a U form, which was by no means generally characteristic. For example, at Dartmouth College, in this print around 1850, all the building were strung out in a line in a rise above the common of Hanover. And the same thing was true of Yale University-- Yale College at the time-- which was on the New Haven common ground just stretched out in a line worked out by Trumbull, who was the university advisor of the time.

It was not very much later-- that is, in the beginning of the 19th century-- that conceptions of the college as an organized organism began to take place. On the right you have Union College, which was designed by the French-American architect Ramée in 1813 and conceived as you see it here with a central focal building and others around it.

Now, the focal building of these days, I think, was different from the kind that we're going to be talking about today. It was an urbanistic event, and in fact one of Jefferson's Virginia on the left was very much like Ramée's conception. It was a round building with a portico in front, a kind of Pantheon recollection. And the Ramée scheme is interesting in that this very rigid French type of organization was surrounded by a picturesque English garden. So there was always a kind of eclecticism in the conception of the American campus.

I don't know whether the choice of Ramée was due to a desire to suggest the kind of Greco-Roman background. The ideology of campus planning really developed later. Jefferson had a very clear idea of what a university should be. He put the different disciplines in different pavilions-- as you can see on the right. The library is the building on the far left, and these pavilions that are joined by porticoes, the pavilions on either side, were places where the discipline was-- each discipline had a professor who lived upstairs in the pavilion, and the students were downstairs. This was partly to distinguish the intellectual environment in this way and partly for crowd control. The professor was supposed to be able to take care of the students who were living in the porticoes underneath and keep them from rioting, which was a very characteristic thing for students to do at the time.

Now I can't see my notes. Anyway, I think I know what I'm going to say.

So each of these pavilions had a different architectural style, and it was Jefferson's idea that the style of the building would teach architectural students about the history of architecture. It was rather a ditzy idea. One of them is taken out of Palladio's Four Books on Architecture. So that was interesting to me.

Now, after the classical start, we have a plan for the Michigan University of 1838, which you see on the right by Alexander Jackson Davis, who did universities a lot. He was perhaps the first architect to be continuously hired by universities, NYU among them, and could change styles at will. Here is the Gothic plan for the university, which envisioned the single building at the start where a whole environment that could be developed later. That was not accepted, and the actual Michigan campus looked the way it does on the right here in 1850, which was the same thing as Dartmouth and Yale, just a string of buildings.

Now, the next stage was in the later 19th century, and there's a big change at that time. For example, you see here on the left the College of New Jersey, which in 1896 became Princeton. And it followed the idea of their most famous president, Woodrow Wilson, that it be a place, quote, "to those who would learn and be with their own thoughts." And so it was isolated from its environment with a cloistered system.

Of the right, you see a design in 1890 for the University of Chicago. And here the Gothic dominates also. This is undoubtedly because of the thought that the Gothic period was one of contemplation and enrichment in the model of the English university. Now, we're in the 1890s, and at that time, these colleges increasingly developed into universities. That meant a great deal of physical diversity. The buildings had to serve different purposes, and at the same time as some of the establishments were being done in a very highly organized way, others began to have to build buildings that didn't fit the plan because they had new functions. Rockefeller was behind the funding for the University of Chicago which you see on the right.

In the late 19th century, the issue of styles became very important because the style of the architecture was intended to express a particular attitude towards learning. For example, Princeton was bitten by anglophilia at this point, and it was largely an Episcopalian organization. So the attachment to the British college environment of cloisters was very strong, imitating Oxford and Cambridge. The display is one of monkish learning and closed from the community.

I didn't intend to find such an unrevealing slide as the one on the left. But when I did, I thought, that does show the relationship of the university to the community.

[LAUGHTER]

Now, at the same time, Columbia in the mid '90s turned towards the classical, driven by, on the one hand, the Beaux-Arts background of leading architecture at the time-- this was [INAUDIBLE] and White and, on the other hand, by new attitudes toward learning. This was the start of the elective system, and there was an enlightenment background rather than the cloister as the model. And the same, of course, was true much later on at MIT, as I think you'll hear shortly.

And finally, the last stage in the planning of the American campus-- for reasons of time, I'm leaving Stanford University out of the picture, because it's eccentric with relation to the respite-- Illinois Institute of Technology dates from 1939 and designed by Mies van der Rohe. And the ideology of modernism now supplants that of historical association with an attempt to get away from this attachment to particular historical background. And his original plan was continued in later construction.

And I want you to note that the organization of the buildings are quite different from the style. The style is absolutely modernist. The organization is quite classical-- The central axis, the buildings that go off forever. It's a kind of a conception that's very hard to add on to in the casual way that occurred in other places.

Now, the second part of what I want to speak about is the the individual building. The beginning of turning to architects because of an interest in their own mode of expression, I would say, came with Seaver Hall at Harvard in 1878. Harvard also has the University Hall by Bulfinch, but that was a fit-in building. This is a fit-out building. These are increments which are related to academic innovation. This is the first classroom-- all-classroom building of importance in the American tradition.

So we're getting one building at a time now. And the new buildings are either anonymous or seeking to blend into the background, or they stand out because of architectural distinction. And the realization of this goal required employing architects and willing to give them substantial leeway in developing design.

And now coming out to more recent times I'm sure you all can recall a number of instances of what might be called signature buildings in different university settings-- on the left, what they call The Whale in Yale University, a hockey rink designed by Eero Saarinen on the right. Richards Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania, 1958, which you see here by Louis Kahn. The Saarinen building is, I think, 1953. The same is true of the dormitory by Aalto at MIT, although that does fit better than most of these, and the Carpenter Center at Harvard, which fits less than most of these.

Now, finally, there's a very interesting phenomenon that when Illinois Tech had to grow and a new architect of repute came into the picture, the original conception was so strong there that even a very far-out architect like Rem Koolhaas fit into it in part of his conception and out of it in another part. But this building which I haven't seen in the flesh seems to be representative of the tension that I've been speaking about.

So let's ask the questions which I'm sure will be discussed in the panel about what's behind the signature building. First of all, fundraising is an important element, the patron demanding distinction rather than blending in. And there's commonly, really since the beginning of this century, an abandonment of a link between a philosophy of education and its embodiment in a historic style. So the style then becomes independent of the theory.

A signature building is a feather in the cap of the university. Striking buildings attract attention and publicity and give a desirable impact on potential applicants to the university, and seems to express up-to-dateness and modernity. And finally, in earlier times, while skilled purveyors of Gothic and classical styles that might have been the same people were often the most qualified for the job, today the most qualified bring with them bold, though often exceedingly costly and sometimes unworkable, individualized proposals. Last of all, architects' reputations are based on his or her singularity. The university purchases a distinctive style as much as the skill and executive ability of the designer. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

ALEXANDER: That's not the way I want to start. Great. Thank you. Good morning, everybody. I knew as soon as I saw the laptop go off the podium, it's going to be a rough start. Good morning.

Architecture may be called the prose, as sculpture and painting are the poetry of art. Its first principles are truthfulness, good sense, perspicuity, considerations of method, order, form, clearness, precision, and sobriety, are what make a good working style, both in writing and in building. So said William Robert Ware, the founder of MIT's Department of Architecture to William Barton Rogers in 1865 as he stood on the brink of inaugurating their new program.

In a constructive place, as artists and scholars as diverse as Eudora Welty to Simon Schama, even to William Ware have observed, exerts both the most mundane and the most powerful influences on our sense of experience, of memory, and of myth. The power of place and the ability to create a sense of place through identity is what gives the study of architecture its driving force. Today I'd like to offer some thoughts about the particular opportunities that the building of MIT provided, both the challenges and the things that fostered a shared sense of place throughout American culture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The architecture that has defined MIT's campus through a century and a half has been the embodiment of the vision of its founders of 1861. These builders of structures and institutions were cognizant of the educational design on which they embarked, and that was itself an experiment. They were sensitive to the ways in which their efforts would be recognized and scrutinized in the public sphere. Through war and peace, prosperity and depression, achievement and crisis, conquest and calamity, this architecture has been designed to represent a progressive, innovative, and yet eminently practical vision of what an institute could be. The philosophy and mission of MIT have been reflected in an unparalleled melding of architecture and pedagogy, and despite occasional lapses and nuances, this vision and its representation, whether it be in built architecture and curriculum, has been remarkable for a constancy of thought.

MIT's campus architecture is a progressive and innovative embodiment of the goals, principles, and vision of the Institute, although these goals and objectives have changed and evolved over the years, as they continue to do today. William Barton Rogers and the founders in 1861 were extremely aware of this experiment at hand. And I show you here two views of the Rogers Building in Boston's Back Bay. The building in the foreground was the building of the natural history on the top screen, and on the far portion of the upper screen was the MIT building, the tech building.

The first physical manifestation of MIT, an expression of its informing principles, may be seen in this building. This represented what was considered the high style of the day at mid 19th century, with its French academic character, detail, and flourish. Whoops. Significantly for its contribution to the public sphere, MIT's founders were able to cite their inaugural edifice boldly within the cusp of a much larger experiment which was the shape of shaping a public space, which was the creation of Boston's Back Bay. Allying themselves with the Society for Natural History, the founders had petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for a grant of land, a request which the legislature eventually conceded.

Furthermore, not only the physical act of filling the Back Bay was an important achievement, but also following the grand scheme loosely that Baron von Haussmann had evolved for Paris. Elegant public buildings, wide boulevards, mandated height and building setbacks signaled Bostonians' aspirations to be ranked among the community of civilized nations. Even the drawings for the Rogers Building were sent home from Paris, where the architect William Gibbons Preston was studying at that time.

Transcending its elegant appointment, the Rogers Building was consonant with the very practical needs of the Institute and was highly functional-- classrooms, libraries, laboratories, museums, offices, and so on. In short, it was an ideal building in an ideal location to carry out ambitious, post-Civil War educational goals in the initial departments of chemistry, physics, engineering, mathematics, and architecture.

It's interesting in terms of the design of the Rogers Building that it was so based on French prototypes that was prophetic in terms of the teaching in the department for many years. In 1872, MIT brought in the first French professor to teach architecture in the person of Eugene Letang. And this French influence of the École des Beaux-Arts would continue into the 1920s and '30s, all the way up through Jacques Carlu, and to a lesser extent, Lawrence B. Anderson.

I'm showing you here Frenchman Désiré Despradelle-- who has one of the most interesting monikers when you read it as an American, of constant desire, Despradelle-- quite an interesting character who inspired his students in very new ways. In his building right across from what was the Technology Building, the Berkeley Building. The role that the Architecture Department also played in the shaping of core values is one I will touch on today for their times throughout the history of the Institute when the faculty and students in the department play significant roles in shaping the campus in its ideology.

That Rogers envisioned architecture as one of the original departments is clear in his original scope and plan. He brought in the young dedicated William Robert Ware, who I show you here, left, in a toga at a party of George Post House in 1885, and one of his buildings in the Back Bay, the First Church. Ware would go on to found the Department of Architecture at Columbia as well.

While Ware turned to the École des Beaux-Arts for a well-honed time-honored system of instruction, he visited numerous practitioners throughout Europe and spent a particularly productive time in England, bringing back drawings of models and photographs for the fledgling Architectural Museum, another first. I show you here images that Ware collected abroad from English practitioners on the top, and down below one of the drafting rooms. The idea here was that the instruction was practical but also visual and very, very tactile, and by being surrounded by these objects and artifacts, that would become a way for you to learn. There was also a very strong sense in Ware's pedagogy that it was a way of elevating public taste and public education. Many of the students-- this was a land grant college, if you'll recall-- he felt would never get to travel to Europe. So instead he tried to bring the whole of Europe back to his students.

So the Rogers Building, then, was a paradigm of progress and new vision. It was a school of technology and science, as opposed to a school of agriculture. The location of the building also signaled a new vision-- it was the latest design being sent from Paris. There was numerous firsts associated with it. It was young, it was progressive, the faculty was well trained and well educated. There was a focus on physical as well as mental rigor, and of course, what we hear so many times at MIT, learn by doing.

By the late 1880s and 1890s, it was very clear that this experiment had been a success. And MIT had long outgrown its original campus buildings. There wasn't a campus there. There was no more room for expansion. The Back Bay had become very crowded. And the Institute began looking for a new home.

This time, the Institute chose an area that was not currently under major development and moved to the riverside in Cambridge. The chance for the new technology to fulfill the vision of Rogers and the founders was seen as inextricably linked with this particular site. I'm showing you here a view, again by Désiré Despradelle, the Frenchman, because there were certain things and qualities in this initial design that carried through many subsequent designs.

This was complete about 1912, just before Despradelle died. But I'd like you to see, obviously, the strong axial plan, the Beaux-Arts symmetry. But one interesting thing that follows through with Despradelle is the connected aspect of the buildings, and that's something that we'll see happening over and over and over again. A sub-theme that could have been developed today also in terms of patronage were the various squabbles that continued throughout the various buildings. As late as the 1920s and '30s, we still have architects who came up with designs and engineers who felt that they were not rewarded for their efforts on behalf of the Institute. And the letters in the Institute Archives speak well to that.

So if you think of Cambridge and the new technology as a fulfillment of Rogers' and others' vision-- and now, of course, the Institute is headed by Richard McLaren-- you get a sense-- I'd like to take a little shift here-- a sense of the public palpable excitement over the new building, or the new buildings. In 1920-- I took a scan through about five different tour guides and tourist brochures that were completed. And there was such a palpable sense of pride and excitement over the new technology. And you see it everywhere. Everyone was using, everyone was talking about it. And as one of the guides quite simply states, the Tech is simply the best in its field. This is 60 years after founding, which I think is an impressive amount-- impressive thing to accomplish in such a short time. Not bad for a small, modest land grant college at its start.

For its next venture, the Institute selected one of its own, William Welles Bosworth. Bosworth was an alarm. He'd studied in Paris. And I think that's another theme that carries the early years of the Institute is that the architects were either faculty or former students. And so the Institute had a pattern of going to its own to help it further its vision. So there's this very strong intertwining of the teaching system coming back and then influencing the architecture.

Now, I think at first glance you might feel that there is a bit of a pedestrian quality to the classicism of Bosworth's scheme. But it ended up being a very, very influential design. We've already seen some elements of classicism. This is a return to classicism. I think in some ways you can think of it as a return to normalcy after the horrors of World War I, something that MIT was thinking more and more about and would continue to think more about as we reached into the World War II period.

Also, it embraced a number of new technologies. Some of my favorite visions of this building are where you have railroad-- and I should say of Killian Court-- where you have railroad cars, spurs bringing in supplies, right next to horse and donkeys with carts. So there's this sort of changeover going in terms of transition and technology. Ultimately on Mass Ave, Building 7, had poured in place concrete, factory sash metal windows, so that you have, again, sort of a tension between the actual architecture and the creation of that.

The Great Court and Rotunda was dedicated in 1916, with additions made through the 1930s when 77 Mass Ave finally opened. In another aside, the Architecture Department was actually the last one to move to the Mass Ave address, remaining holed up in the old Rogers building with their French Beaux-Arts drawings and medieval sculpture, something which made the Institute realize it was high time to get them into Cambridge.

The first building to break with the Bosworth axial plan-- again, we turn to student and faculty member Lawrence B. Anderson, working with Herbert Beckwith in 1929 with a swimming pool. And I'm showing you two views. For those of you who are familiar with the swimming pool and you see the new Stata Center behind the pool, you'll notice how much the disposition of this building has, in fact, changed. But it was quite, again, a very important moment for MIT, not only in terms of breaking with the original master plan, but also because of what it said about the importance of physical and athleticism to the student body this time. There were great many thoughts going on about how do we keep not only the mind healthy but the body healthy, and the swimming pool was one of those.

If the new technology was fulfillment of vision, the post-World War II campus questioned that vision tremendously. I'm sure many of you know this image as Building 20, which was certainly eminently adaptable to scores and scores of uses and dearly loved by many students and professors. What I'd like to do is talk about the post-World War II vision as embodied by Baker House and what that meant for the Institute.

It represents a tremendous shift in thinking at MIT following the upheavals of World War II, and it caused MIT to begin thinking about offerings for its students. There were a number of things that happened, including the Lewis Committee. The Lewis Report was issued in 1949, which had far-reaching curricular recommendations. And among those recommendations was the formation of a new school of humanities and social science. I think that's something that a lot of people aren't aware of in terms of how long the connection with humanities existed at this institution.

It was of considerable importance to MIT this time as well because MIT was still largely a commuter school, and the idea of having a residential life component was seen as very, very important in terms of creating a humanitarian vision for the students. One of the singular events leading up to this was in 1949, MIT hosted the Mid-Century Convocation. And the convocation actually began with Winston Churchill's speech in the Boston Garden. And as his backdrop was this view of Baker House. Baker House was the future, and MIT was the future. They were inextricably linked.

Bringing Alvar Aalto to MIT, for that we need to thank William Worcester. And I think Worcester is someone who frequently does not get the attention for the role that he played here at MIT. You can get a sense of his excitement when Worcester says, "Aalto flew here. So comes fresh from the problems of reconstruction of destroyed towns in Finland, I would say that possibly the greatest contribution is adding richness to the stream of teaching in the school which gives zest to each problem for each student. Professor Aalto is not to conduct a studio for a few, but rather to meet with each group and each individual during his term." So here again, we have a link between teaching and building ideology.

Here I show you an anterior view shortly after completion. Aalto said about Baker House in a letter to his wife, "I've improved almost every part of the building. Now it is really going to be good. It always happens that the real inspiration comes and the exact forms appear only after construction has started. As for the additional rooms, well, it went exactly the way you thought it was best. Keeping the basic form of the building with some improvements but increasing the number of rooms with a stepped extension on one end turned out best. As always, your instinct was right." Now, you can sense how excited he was. But of course, a number of these expansions were cut due to budget restraints. So--

After the influential Lewis Report, the Institute moved forward into the second century campaign. And that generated a series of other very important buildings. And I show you here on the far screen the Kresge Chapel and Kresge Auditorium, again by Saarinen. And on the opposite screen, the Student Center by Eduardo Catalano. With the second century campaign, the focus was again on providing facilities for the students and, again, returning to those earlier visions and goals and founding principles about student activity, student life, and a well-rounded environment.

The Wiesner Building again shows MIT going back to its students. I show you here a photograph of the Wiesner Building. And in the upper corner is actually a student drawing, a thesis drawing, by the architect IM Pei. IM Pei was a student here in 1940 and completed some very, very interesting work at that time as a student. He was brought to MIT also in the 1960s for the Green Building, and then made a return appearance here with Wiesner.

This was a building that, again, had a very long gestation period based on-- actually going back to 1960, '61-- based on what were the needs of the students at this time. How do we bring creative activities and art into the lives of our students? So again, you have the Institute turning to its own and coming up with something that fits-- is a good fit for its student body up to this point.

In conclusion, I'd like to just go back to Alvar Aalto, one of-- I think a telling quote for this, in which he says, "True architecture, the real thing, is only where man stands in the center." Aalto's remarks remain as compelling today as they were when they were spoken over 50 years ago. Is one's perspective, where one stands in relation to the center or the place architecture occupies in one's worldview may shift, but as we can see in the vision of the founders, faculty, and students, we always return to the same principles. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

VEST: well, being the one true technologist here, I'm only using notes this morning. I get very nervous whenever I'm asked to speak to groups of artists and architects and musicians and such people because I don't know very much about the subject. But I always hearken back to one of Victor Borge's comments he used to make, which is-- he would introduce himself as the music critic for Mechanics Illustrated. So just kind of think of that.

So with all this in mind, I said to Bill Mitchell yesterday, Bill, what should I say tomorrow? This is a very important forum, and there's nothing worse than somebody who actually doesn't know about architecture learning a little bit of the phrases and all that stuff and standing up and pretending to know something. So Bill said, Chuck, your job tomorrow should be just to tell the truth about what it takes to get something like what we have accomplished here done.

And I said, Bill, tell the truth? You're not serious. And he said, well, tell a little bit of the truth anyway. So that's what I'm going to try to do today is speak a little bit of the truth of what we have been through in this really last decade when it comes right down to it, because it has been a remarkable adventure.

And I want to begin saying that I suppose if we sat down and made a list we could probably identify 1,000 people who one way or another have had something significant to do with the transformation of the campus that is now well underway. And there would obviously be 1,000 different realities. So I am only going to give you a bit of mine. And let me start with a couple of observations, and I will apologize in advance for some of them.

When I had the great privilege of coming here to MIT as president in 1990, two things happened that were short of traumatic experiences. One is that I took my first drive down Vassar Street. And as you know, I came to MIT literally from the outside, with a great sense of reverence and awe for what went on at this Institution. And I could not somehow in my mind put together what I saw on Vassar Street with what I knew was the reality of the Institution.

And the second sort of weird epiphany was during the interview process, they put me up in the suite on the top of the Marriott looking down over the campus. By the way, it was the last time they put me up in anything of that expense. And I remember standing out there looking down on top of the campus from that height and distance and sort of seeing all these rectilinear lines with two big flagpoles. And for some reason, the image that kept coming into my head was a Naval base.

But then there's the other side of the campus. After I came here, every morning it's my habit-- including this morning, at about 6:30-- to get up and go for a jog. That's how I get my mind in order for the day. And I absolutely fell in love and in awe of the sight I would see every morning running along the banks of the Charles River and looking into the Killian Court and the Bosworth Buildings and cutting back behind the dorms and going by Baker House and so forth, different every day, different quality of life, different this, that, the other.

And so we had this kind of juxtaposition of something awful and something really quite wonderful. And yet some level, none of these seemed to reflect the wonderful extraordinary reality and excitement electricity of what goes on inside all of those buildings. So with this in my mind, I formed a grand well-organized vision of what I believe this campus needed to be for the next 30 or 50 years, started a capital campaign to raise the funds, knew the right architects to hire, and got the job done so it will stand as my personal vision and legacy.

[LAUGHTER]

[APPLAUSE]

Now, of course, none of that is true. None of that is true, except for the first three observations. And just to tell you how untrue it is, I was remembering the other day-- we have something here called a campus visit, where we have friends and alumni and donors and so forth in to meet faculty and students, see what's going on. They always come to dinner at the president's house at the end of the session. And I always answer a few questions.

And I remember the first year, somebody asked me the question, what's the situation with deferred maintenance on campus, and do you anticipate building a new building for something or other, and so forth. And I distinctly remember that my answer was, understanding MIT's budgetary situation and as best we could project, I did not believe that we would build a building during my tenure. Well, as it turns out, when I stepped down next fall, recognizing that a lot of the space I'm going to refer to is in housing system and so forth, we will actually have constructed about 25% of everything on the MIT campus. So much for vision.

My good buddy and hero Gerhard Casper, who was president of Stanford during much of my tenure, called up one morning in his third year as president. And he said, Chuck, I just got to unload on somebody that if one more person asks me what my vision for Stanford University is, I'm quitting, because I don't have a vision for Stanford University. And I really understand what all that is about.

But having said that, let me make a few serious observations. We are, as has been said much more eloquently than I can say, really in the midst of a very profound transformation of our campus that I think of as an effort to better reflect and support and inspire what the extraordinary people of this institution do. That, to me, is what it is all about.

And while I don't know much literally about architecture, I do know a lot about universities. And I have sort of a basic theorem about how universities-- great ones, at least-- evolve. And when I say evolve, I mean intellectually and socially as well as physically. It kind of happens roughly by 50%, by planning and strategy, and at least 50% by serendipity and opportunism. And I use opportunism in a positive sense of that word. It means faculty recognizing exciting new intellectual or other opportunities.

It's not like an orchestra with a conductor, despite the fact lots of people like to write about themselves or others as conductors. It's more-- at least here, it's more of a jam session among a lot of very talented musicians who start kind of listening to each other and get into the flow, and people like the provost and executive vice president you'll meet in a moment and myself try to kind of keep all that going, see if we can get the right musicians and listen to the pieces and so forth and so on. That's more to me the way things happen.

The second serious observation-- which being MIT I even did as a plot one time of all the square feet on this campus coming in and out over the period since we moved across the river from Boston-- the opportunity for campus development, the kind of thing we're going through now, it simply comes in waves, with a period of about 20 or 30 years. And there are obviously good reasons for that. It's driven by two things primarily, I would say. First and foremost, to be honest, the economy. Economy gets better, you could do some things. Economy gets worse, you have to pull back.

But juxtaposed on this are a couple of things which are the intellectual trends, what faculty are doing, especially in a place that's focused largely on science and technology, as we are here. And secondly some of the kinds of thinking that both of the previous speakers referred to as kind of views of what the life on a campus should be, how our students should be, what's the humanistic role, and so forth. That also creates opportunities as we move forward. So I think as we headed into this sort of pivotal moment in roughly 1997, '98, through those two years, MIT, and to a lesser extent I, had what in the sciences we often like to refer to as the prepared mind. There really was not a well-formed vision, but there was a lot of thinking about what is going on in the world, what's going on here, that I think put us in a good position when the moment came. And when I say "the moment," it means that literally in that sort of two-year period of '97, '98, it became crystal clear that we had an opportunity to create some things of historical import in the development of MIT. And I say of MIT because I'm not just talking about physical facilities.

What were some of the inputs to all of this? First of all, while people were churning out books about the end of science and things like this, the fact is, we were entering what I believe is the most exciting period in science and technology in human history. And so these enormous new opportunities out there in terms of the melding of the life sciences with the physical sciences and the information sciences, and we started hearing more about neuroscience and biology and nanoscale science and technology, and on the larger scale, environmental issues, computational, systems biology-- all these wonderful, rapidly, rapidly evolving new areas in which people were coming together across all kinds of disciplinary boundaries, to work a very, very yeasty time. And we're still very much in the midst of that.

Secondly, there was a very important report that was finalized in '98 by a group that, together with Ros Williams, who at that time was our dean for education, that I had commissioned in '96 as a task force on student life and learning. It really was to be sort of the next version of the Lewis Report that was referred to earlier, to think through what it was that we owed to these remarkable students here in terms of their education and their experience.

And that group came back somewhat unexpectedly not focusing with a lot of detail on what the intellectual content should be but saying, we've worked for two years, we've listened, we've looked, we've talked to everybody. And we think that MIT needs to stop thinking about itself as resting on two pillars of teaching and research and start thinking about itself as sitting on three columns, which they called academics, research, and community-- a feeling that we had created a separateness of our students and the way in which they were housed and lived from their learning environment in the classrooms and laboratories and that we really needed to become a better integrated academic community.

That report, we all swore, was not going to gather dust on a shelf, and it in fact drove a lot of our budget. It drove the way we restructured the administration. And a lot of it is reflected in the things that are beginning to happen now architecturally on the campus.

There were, as also was alluded to, rapidly changing forces, especially for MIT, in what it took to compete for the very best students. And underlying all of this-- and it's a whole lecture in itself, so I will just mention it-- was a dramatic and relatively rapid restructuring of our finances, as we moved out of an era in which we were driven to a very unnatural extent by federally sponsored research to a future in which we were going to have a more balanced set of resources, drawing much more on the private sector in the form of both industry and private philanthropy.

So this kind of moment arrived, and I sort of knew what had to be done, and we began building a great team of people around the administration. It kind of gave me a little bit of a rejuvenation as I moved into kind of a second phase of my presidency. And in '98, I published the closest thing that anybody could claim was an actual vision. It was a document called "The Path to Our Future." And that document was not just personal thought. It was a reflection of what I was hearing and learning from all kinds of different directions in the Institution. But it did kind of guide our pathway forward.

But if you look back at that document, it's about core function. It's about what does it take to attract and enable great faculty and great students to do what they think is important, and to continue to be an institution that does not look inward but looks outward and always likes to take on big, bold challenges and influence the world around it. In many ways, the adventure of this campus transformation, as it properly should be, is all about people. And it's about trying to seek out the right balance of continuity and change. And we certainly have built on the years of dedicated work of people like Bob Simha, our campus planner for many, many years, and Bill Dixon, who was our Senior Vice President when I came here, and there's a lot to allude back to and to be grateful to them.

And as we began to go about this transformation, there was one person who played a singular role. And to those people who do not like what is going on on the campus, I will refer to Bill Mitchell as Rasputin. To those who like what's going on in the campus, and I certainly am among those, I'd like to say it's been an extraordinary privilege to have Bill serve literally as the Architectural Advisor to the President, and his wisdom and his balance in not pushing things but showing opportunity and how to think about certain things has meant a lot to me personally and certainly means an enormous amount to the campus.

Well, kind of to move a little bit toward closure here, I want to just comment on one thing, which is sort of emblematic of much of what has gone on here, was the process by which we decided to ask Frank Gehry to design the Stata Center. And I'm sure this goes back into the 1,000 people, 1,000 realities, but this one's the real reality.

With the help of Bill Mitchell and Vicky Sirianni and so many other wonderful people, we had put together a very formal process. And we had selected 20-some architects to do what we knew was an enormously important project, to bid on it. And I believe every one of them responded. And then a process was set up that would end up with six finalists. Two, if you'll forgive me, I will classify as looking for two world-class architects, two really good architects, and two young up-and-comers. That was kind of the goal. And there was a committee with which I was not really even terribly deeply involved of faculty and administrators who had gone through all this, narrowed it down to six, and then ultimately narrowed it down to two.

And we sat around the conference table, and they were ready with their report. And I asked each person to tell me who they thought we should select and why. And lo and behold, literally 50-50 split between two architects.

Now, as I implied at the beginning of these remarks, the president of a university may claim to sit around the office and make lots of decisions, but the fact is, you don't really do it very often. But here we had one. And so I went down, I sat in my office around the coffee table with that wonderful gentleman, Bill Dixon, who had led Construction here I think since he was a freshman, and who had a lot of wisdom.

And I knew in my heart that I wanted to go with Frank Gehry, because I knew we had to do something big and bold and exciting and different. And I figured, if I could convince Bill that this was the thing to do, I would know that it was the right decision. So we chatted while. And I tried to tell Bill my thinking.

And in the way only he could do, he thought a minute and he said, well, let me tell you something. He said, back when the Kresge Auditorium was designed, it was-- I'm sorry, not Kresge Auditorium, the Chapel. When the Chapel was designed, it was considered so radical that the foundation pulled their funding from it. And look at how we think about it today.

So I said, sounds like we know who we need. He said, right, let's go. I said, you make the call.

Now, at that time, what was the risk in my view? The risk was not whether Frank Gehry would produce a remarkable and wonderful facility for us. The risk was would he know how to listen to the clients in the right way? Because I come back to the main point-- I'm not interested in having signature architects for the sake of having signature architects. And I don't want something looking big and exciting just to be big and exciting. It's got to reflect what we are and what we do, and above all, it's got to be a place for faculty and students to live and work.

So after Bill had called him, I called Frank up, and we talked for about 25 minutes. And about 24 of those minutes was Frank telling me stories about Richard Feynman. Now, if any of you know enough about physics to understand Richard Feynman, you would know that that was signaling something to me about what this guy really understands. And he clearly knew what the importance of replacing Building 20 was and so forth. And so I finally entered into that particular phase of things with great confidence that we would get what we really wanted.

Now, a couple of beliefs on my part. Again, reflecting back to my early years here, basically during my first year, I sat down one day and had an interesting talk with a wonderful man named Peter Reich. Peter Reich headed the psychiatric service in the MIT Medical Department. And he said to me one day, you know, MIT is the best place in the world to be a psychiatrist. So I said, what are you talking about?

And he said, well, I've worked on several university campuses and other venues. And he said, most places, if you're a shrink, people come in and they come to see you, and they sort of turn up the collar of their overcoat and they look at their shoes and they slouch down, and it takes two or three visits before they even get around to saying what it is that's bothering them. But he said, ever since I've been at MIT, people just kind of stride in my office and they look in my eye and they think, well, this is a professional just like I am. And I'll bet he's as good at being a psychiatrist as I am at being a computer scientist. So they just tell me what the trouble is, and we go to work.

So with kind of that in mind, I came up with a theory of how you should do campus development, which I'm going to term faith-based campus development. And what that means is you get the right people for the right reason, and you let them do their job. You have to have faith in them.

So all of this to me is about function, not about monuments. It's about enabling and inspiring and respecting and reflecting but also about raising our sights. And I deeply believe that the things that have happened on this campus with Simmons Hall and the Zesiger Center and the Stata Center and what you're about to see evolving in the Brain and Cognitive Science project and hopefully in a couple of others that are still on the drawing boards, it is going to raise our sights as well as reflect and enable what we do. And it does in my mind-- and this is one part I will be very serious about-- it is all intended to reflect a great boldness and confidence in our future.

But I want to tell you-- and I think this is the truth part that Bill wanted me to come out with-- it's been hard. It is not an easy task. I transformed myself into what I think of as a snapping turtle-- namely, once we got moving to accomplish these things, I had to sort of just grab on to people and things by the ankle and not let go until we got done. There are so many constituencies, as you can imagine. Faculty, students, trustees, alumni, donors, the federal government-- they all come into play. And there are enormous forces.

And the two forces that I think cause the deepest angst and biggest problem with accomplishing something wonderful and extraordinary, as is happening today, are first, the economy. That is clear. We started into this, we were enabled to become bold and do some things in a relatively short period of time, because the economy was going up. But lo and behold, just about the time we got well into it, the economy went down. And you can imagine the things that that creates. You have to really persevere.

Secondly, something I read a long time ago, in all places, in a chapter in Henry Kissinger's autobiography, he used a term, debilitating nostalgia. And I kept wondering for years, what does that mean? Because quite frankly, I'm a nostalgic person in the way I think about my life and so forth. But in the years, both at Michigan and here, as an academic administrator, I came to understand what I think that term really meant. And there is this weird balance you have to find between looking backward in the right way to understand your heritage and where your strength comes from as an institution and what needs to have some continuity, and not getting so caught up in it that you don't do the really exciting forward-looking things.

And I've been debating since I sat down this morning to put these notes together whether to say the following or not, but I think I am going to say it. About two years ago, maybe a little more, as our building program was getting underway, we took the Academic Council and a few other friends around to visit everything under construction. And as I was leaving, one of my colleagues said to me, this must really make you happy to see all this going on. And I looked at him and I said, the truth is, this has been so hard and so painful to keep going that I don't feel very happy right now.

But having said that, yesterday-- yesterday, we wandered around in the sunshine with faculty and students and donors on some of these marvelous outdoor spaces on Frank's Stata Center, and I can tell you, it has all been worthwhile. And I'm feeling just great. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

MITCHELL: Well, welcome back. And thanks to the speakers this morning who really set up this discussion in a terrific way. I have an interesting nametag here. On the front, it says William Mitchell. On the back, it says Rasputin.

Let me just jump in with a couple of quick words that might be useful to set up the discussion, and then I'm going to ask, well, two of the architects I admire most in the whole world to say what they're here to say today. And I think we'll get some interesting discussion going.

As I was listening to Chuck describing the process that we've gone through over the last few years, one thing kept coming back to me was that MIT is an enormously critical place. And nothing around here gets taken for granted. Nothing goes unquestioned, and that's the beauty and the quality of the place and the thing that attracts so many of us into this community, I think. And something that's been consistent right through the process of rethinking the campus and doing the individual buildings has been a constant desire to take each opportunity that came along as a moment for critically rethinking, to critically rethink what a laboratory can be, to critically rethink what housing can be in the 21st century, housing for students, to try to understand how the world is changing, how this campus is changing, and how one might respond in some new and important ways.

And that attitude of not taking anything for granted and rethinking each project, rethinking the premises of each project from the beginning, has been, I think, fundamental to what we've done. And there's been an attitude that all the way through we are conducting a series of experiments. And as all of the scientists and engineers here know, you only really learn something from bold experiments. You don't learn all that much from experiments that don't really put something out on the table, that can be argued about, that can be debated, that potentially is contentious.

So what we've gone through is a set, I think, of very bold urbanistic and architectural experiments, where we've tried to lay out some visions of what the future can be. And what it's generated, much to my gratification, has been a huge amount of debate. Each project we've done has done that. So what we really need to-- what I expect we'll do this morning is continue that debate.

And so I'm going to ask Frank to jump in and say some words about how he sees the process of campus building and what we've done here and what's happened to the particular project. Then I'm going to ask Bob, who promises to be grouchy, and I have no doubt that he'll deliver on his promise. And then we'll see where it goes and take it from there. So then I'll ask-- we have a couple of very interesting respondents who I'll ask at a certain point to come in. Then we will leave some time for questions from the audience. So, Frank.

GEHRY: Well, I'm with Chuck Vest. I'm sort of a faith-based practitioner. And I assume that if I ask enough questions when I'm engaged with a project and I'm dealing with people that are thinking about their environment and what they want, what they need, that I will come away with a road map or a path to which to respond. Now, I don't come to the table with a preconception. If I knew-- I've said this a million times, but if I knew exactly what I was going to do I wouldn't do it, because I'd already thought it through and seen the results and decided whether it's good or bad and then I go forward.

So in the case of this project, the excitement for me was-- and the reason I guess I brought up Feynman in talking to Chuck was that Richard Feynman represented that kind of curiosity and the "cat playing with the ball of twine" attitude that that you would just sort of take things as they are given to you, respond and work on them, and assume that there was some kind of-- you could participate in some way with the knowledge that you bring to the table.

I suppose-- I was raised on Talmudic discussions with my grandfather. And if you've gotten into to any of that, it's all about questioning and why, and then you make a statement. And then he makes a counter statement, and then you go-- but it's a constant inquiry and constant-- it seems totally relevant while you're doing it, but it sort of hones your thinking. And sooner or later, you come up with an essence. In the case of the Talmud, the final essence is the Golden Rule, and everything comes back to that in some way.

I believe that I'm doing that with my buildings, following that Golden Rule, that I want to be a good neighbor, that I respect the other architects whose works surround me-- some of it I like, some of it I don't like. And there is a growing model of urbanism in America, I guess in the world, and I optimistically believe it has something to do with democracy, that there is a pluralist notion and that there is a collision of ideas, which again is Talmudic, and that the collision of ideas is the process by which you come to conclusions yourself, you make a statement, and you hope that it has positive effects.

The collage of parts at the Stata Center, I can take-- I should probably do this, just go around Cambridge and take pictures, showing you that there's an extraordinary precedent for everything I've done, and that we just don't think of it that way. You think of buildings as individual buildings. And if you look around, you'll see that they are really pieces of buildings collaged on each other-- you don't see the whole buildings-- and that they create a kind of an urbanism, and that I was just continuing with that.

The Stata Center is a huge, huge building compared to others on campus. And I was trying to break down its scale and humanize it. I made many studies of what it would be, just as a simple block, which would have fit more into the campus as it was. That wasn't why I was brought here. And as we responded, breaking down the mass of that, the user group seemed to respond positively.

The interiors of this building are not finished, finite interiors. They are a very open-ended system. The idea is that the rugged individualists who are inhabiting it are going to intervene. They're going to bring their stuff in. They already have. And over time, this building will change and become theirs. I believe it's strong enough to survive that, but we'll see.

I don't think everybody's going to like it. I think at the beginning-- the complaints I've heard so far are all fixable. They all mostly relate to-- they don't have the privacy that they want. Everybody would want a private office with a view and close to the bathroom or something. That wasn't possible. But I think over time, it could be completely enclosed into private offices, if they decide to go that way.

You know, a lot of positive feeling in the meetings yesterday, but we'll see over time whether it really works. And I hope it does. And you can't use your cell phones in there, and I suppose I'm going to get blamed for that. But we've created a Faraday--

MITCHELL: Faraday cage.

GEHRY: Faraday cage.

MITCHELL: We can fix that. We can fix that.

GEHRY: Okay.

MITCHELL: That's no problem.

GEHRY: I didn't want to create a Faraday cage. Okay, Bob. Go for it.

VENTURI: Okay. It was explained that we were to be-- each of us was to be a member of a discussion group and not to give a lecture. But what I want to say is so complex and contradictory, I guess, that I've written it down as notes. And I'm afraid it is going to be kind of like a sermon for about five minutes. I hope you'll forgive me.

And as I have pointed out, I'm going to be a bit grouchy. And it's going to be a little embarrassing what I'm going to be saying in some ways. And so those of you who want to boo afterwards, you are invited to do that. But I-- also I was just mentioning that our son Jim is a great fan and friend of Frank, and I want to make sure that any friend here doesn't mention to Jim that I have said a few negative things about him. And also don't mention to my wife and partner that I'm using notes, because she says you should speak spontaneously. But I want to get a lot in real quickly. So here I will go being grouchy.

There's no question that there is a great commitment to the idea of cutting edge-- at MIT especially, but to any academic institution in general. But I would think it is important for an academic institution to employ cutting edge as a product and not so much an image, a cutting edge that engages work and is not necessarily a place. Also it is where the campus is a community, as the president has mentioned. And if I may be mean-- and this is happening a lot elsewhere-- where the campus is a community and not a stage set, which cutting edge can connect with; where cutting edge can happen in context, but should not necessarily be as context-- it should not be all over; where cutting edge derives by vital action and not necessarily via architectural form; where it happens within the uses of the building and not sort of has happened; where creativity derives from communication, on one hand, or let's say where community derives from and creativity-- let's say creativity-- derives from, communication on one hand within the community, on the other hand, very much on focus. It's like the users who want to not be in open offices perhaps.

And there is this inevitable kind of wonderful kind of contradiction and conflict-- that is, a community for communication, but also there must be focus and they must be accommodated. And therefore there should be a setting which is not distractive, which is not intrusive via very often cutting-edge architecture. It should be recessive. And a lot of architecture today is this in general-- let's call it a dramatique abstract and also kind of industrial symbolically. That's kind of an irony in this era. But abstract expressionism involving very often what I call industrial [INAUDIBLE].

God, I'm getting pretty bad here, huh? In a setting where dynamic change happens rather than is expressed therefore, because I think there really is a danger in making a background that is intrusive, as I said. Also via an architecture accommodates flexibility. That is extremely important.

It is a place for functions naturally and accommodation to variations in functions over time-- spatial, mechanical, electronic. And therefore you could say, not where form follows function but where forms accommodate functions, in the plural. Therefore an architecture often in the case can work that's, in the tradition of the vernacular, loft building. And I think this is something we've tended to forget, where there is certain precedent and tradition naturally. Especially in New England, there's the wonderful industrial mill building. There is the academic loft. There is a long tradition, as was pointed out by Jim Ackerman, of going way back to William and Mary, to Nassau Hall, Princeton, to Harvard Hall at Harvard, where the buildings were made as lofts in a sense to accommodate varying uses over time. And the buildings still have iconic quality on the outside, but also are accommodating inside.

There is also another kind of building of that sort, which is the Italian Palazzo, over 300 or 400 years, from the Renaissance through Baroque. It's essentially the same kind of building, with the cortile in the middle, that could over time evolve from the residence of a dynastic family to a library, an embassy, a museum over time.

So I think someone therefore could say-- I remember the Richards Tower that also was on the screen up here. And I remember that when we did our first-- many decades ago at Princeton, our first building, our first laboratory building, I was very aware of the Richards Tower as being not a building that was appreciated by the users. It again had this sort of dramatic quality, with articulations, formal articulations, that did not allow for flexibility. And I mentioned this approach that I would like to use to the head of the Department of Molecular Biology, who would be occupying the building. And he said, oh, I very much agree with you. That building went up when I was a graduate student at Penn, and I was one of the vigorous antagonists who used that building and held up signs against it.

Anyway, I don't want to say something, again, mean about Louis Kahn. But I think it is significant that the loft building does have validity. So you can say, down with architecture as boring originality. I heard someone say that the other day-- boring originality. And I think you could say, in your presence, Michelangelo and Palladio were good rather than original. Michelangelo's dome had really been established by Brunelleschi, you could say, a century before that. It was not signature. It was not egocentric. It was good.

You can say also down with the old romantic idea of the artist as original in order to be good. You can also say, therefore, viva convention and vernacular architecture as convention, where the architect in a mannerist way works to tweak convention rather to invent new conventions. Viva architecture that acknowledges the technology of today. It is an irony that much of the architecture that goes up today sort of engages a vocabulary, an architectural vocabulary, that is essentially based on an industrial vocabulary, which is passe. It also reuses-- not yours, by any means, but reuses the architecture of modernism of 50 years ago. And the revival of modernism 50 years ago is a little like-- just as historical as reviving the Renaissance of 500 years ago, whatever.

So architecture that acknowledges the technology of today-- electronics, not passe industrial, in the post-industrial age. How about sustainability rather than style or structure? And this is, again, electronics, very appropriate for the-- I'm almost to the end-- for the electronic age. So abba old-fashioned, modernist, abstract, articulated form. Viva, perhaps, iconographic surface. Iconic imagery and architecture is important to create identity, and even the Nassau Hall type of building has iconic quality to create identity. But yes, it should not-- the iconic quality should not dominate and therefore be distracting, as I said. So identity via dynamic iconography perhaps, rather than sculptural form, valid shelter, rather than arty sculpture. I'm talking about a lot of the architecture currently of today, which we are reacting against.

Then there's also the issue of respecting the budget. I think that should be considered as extremely significant, a fundamental of that. And I think an institution should do that, respect the budget, because the budget also has to go to other important aspects of the institution. So respect the budget, and make it not at the mercy of vision.

I wrote a book a while back that had an essay in it called-- this is awful-- "The Vision Thing: Why It Sucks." But I can mention it here because the MIT Press published it. And I said, if you want to change that and make that more correct, you can do that. He said, no. The guy said, no, don't do that.

One last little ending I want to put here is my particular love for the original MIT building. And you can say, oh, well, that's what you've been arguing against, isn't it? I mean, blah, blah, blah. But in a way I call it-- the great Complex, the original building. We're doing some interior work in that. In a sense, what you can say, it is a building on the outside which is very much an iconic, grandiose kind of gesture, if you will. And on the inside, it's just amazingly down to earth, vernacular, kind of industrial space of that period, which can accommodate non-distracting environment and flexibility over time for uses and changes that can happen spatially and mechanically and later electronically. I loved referring to it when we were being interviewed for the job-- and I thought, oh god, we're not going to get the job-- as a transvestite kind of building, which is on the outside wearing clothes that are different from the body inside. But very, very appropriate.

And then I also bow, whatever I say, refer to Alvar Aalto's Baker Hall. You have a precedent here which I think is very good. So excuse my being kind of nasty. Excuse my being a bit preachy. But I will end on with kind of-- viva pragmatism. Okay.

[APPLAUSE]

MITCHELL: Frank, you. want to jump in? I saw you take some notes there.

GEHRY: Oh, well, I--

VENTURI: God.

GEHRY: We do this all the time. When he rags on me, his son finds out and makes him call me and apologize. What happened to "less is a bore"?

VENTURI: Yeah, less is a bore. Well, you evolve. You evolve. And as work and institutions should evolve, architects evolve. And they evolve also as a result-- I loved your emphasis on-- you didn't use the word, but you might have-- of "dialogue," of working with a client in that way. We very much enjoy that. We say we get some of our best idea-- we get our best ideas from our clients.

And also, I love the idea of layering. I'm not always in agreement with your kind of layering, but I think the idea of layering is very important. Le Corbusier did it beautifully in a building I adore, Villa Savoye, where you have the exterior, and then inside you have all sorts of different things happening, [INAUDIBLE]. My mother's house does that somewhat. It's appropriate and can be used in different ways. But this isn't really the subject, is it?

GEHRY: Well, our work is very different, as you know. But today you sounded like you're fitting well into the resurgence of fundamentalism.

VENTURI: Oh, my god. You think I should vote for Bush?

GEHRY: I think-- you know, I'm not an evangelist for anything. And I don't really believe-- I don't want people to copy me or do what I do or any of that stuff. And I'm really not interested in creating a school, school of Gehryisms. Strangely enough, there's been kind of a nice response from people to some of my buildings, like in Bilbao-- which by the way, respected the budget, listened to the clients, and paid for itself in the first eight months of its existence. Those were all-- I didn't expect that to happen, but those are all very positive things. And when I go to Bilbao, little old ladies come up and touch me.

[LAUGHTER]

The younger ones don't. I don't know.

[LAUGHTER]

But there has been a very positive response to it. You know, if the marketplace does-- and that's something that you talked about in your writings for years, that it behooves us to somehow connect with the world around us. And I think some of my buildings do. Not all of them. I'm not sure about this one here, but the response has been overwhelmingly positive in some cases. And I look at them, and I'm not sure what they're liking about it usually. But I think I do represent some kind of a humanist attitude that I try to connect with, the scale of people, and I respond to the time and place that I'm in.

And so I get nervous when I feel like you're apologizing for talent in some way, that you're demeaning it. And I don't think you mean to do that. But maybe you do.

VENTURI: No, I just think talent does not involve originality. You can also be somewhat involved in evolution rather than revolution. I think very much in this period we're owed to be cutting edge, cutting edge [INAUDIBLE], I guess. But there's an awful lot of appropriate evolutionary, but evolution is also appropriate.

GEHRY: But who decides what's appropriate and what's not? I mean, if you take every--

VENTURI: It varies. [INAUDIBLE]

GEHRY: --every building-- I can only speak for myself. I probably hate most of the buildings you hate.

VENTURI: Probably. Yeah.

GEHRY: We probably agree on--

VENTURI: It's so easy.

GEHRY: And I think Borromini was an egomaniac of some kind, wasn't he?

AUDIENCE: [INAUDIBLE].

GEHRY: So ego plays a role. It's just that it's tempered so much by-- you know, you get budget, you got client, you got building department, you got processes, you got what's available in building, you have context, you have-- there are so many constraints on any ego trip somebody may embark on that the amount of freedom to express in any architectural project isn't that great. So I don't think even-- you know, if I make 10 more buildings like this one, it's not going to destroy the fabric of America. So it's not dangerous, and it might be positive. I don't know.