"Big City"

[MUSIC PLAYING]

NARRATOR: This is the year 1980. By now half the population of the United States is living in cities and towns that didn't even exist 20 years ago. We had to build them from scratch, the way our neighbors in South America built Brasilia to take care of millions and millions of new Americans.

The rest of us Americans in 1980, well, 90% of the rest of us are living in the old cities. And what are they like? Well, some are pretty good, like Philadelphia. All the way back in 1945, Philadelphia saw 1980 coming and decided to do something about it.

But an awful lot of us didn't see 1980 coming or if we did, we didn't let it worry us. And where are we living? Oh, we're living here. Where are you going to be living tomorrow?

[MUSIC PLAYING]

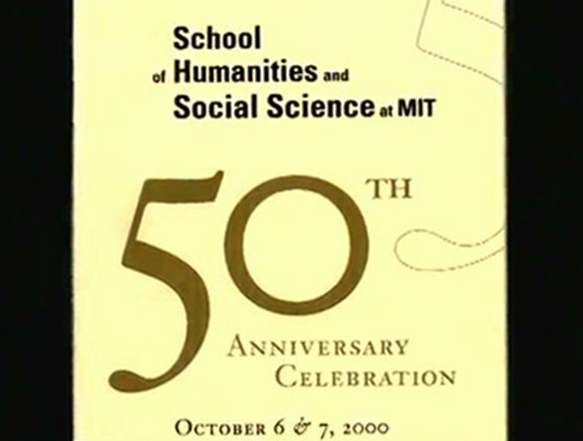

Tomorrow, a preview of the future as it begins to take shape in the laboratories of the world. Produced by the CBS Television Network. Commemorating the Centennial Celebration of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

MOORE: Hello. I'm Garry Moore. We're flying at a speed equivalent to 2,500 miles an hour. That is a metropolitan area on the Eastern Seaboard. Doesn't matter which one because they all look pretty much alike today. Yet the experts tell us our population is going to double, twice as many people down there.

Now, where are we going to put them? In brand new cities? In remodeled old ones? In cities under the sea? In skyscrapers a whole mile high? These are only some of the proposals we're going to see tonight as we look forward to big city, 1980.

NARRATOR: Big city in 1980. With you host Garry Moore. In a moment, that story.

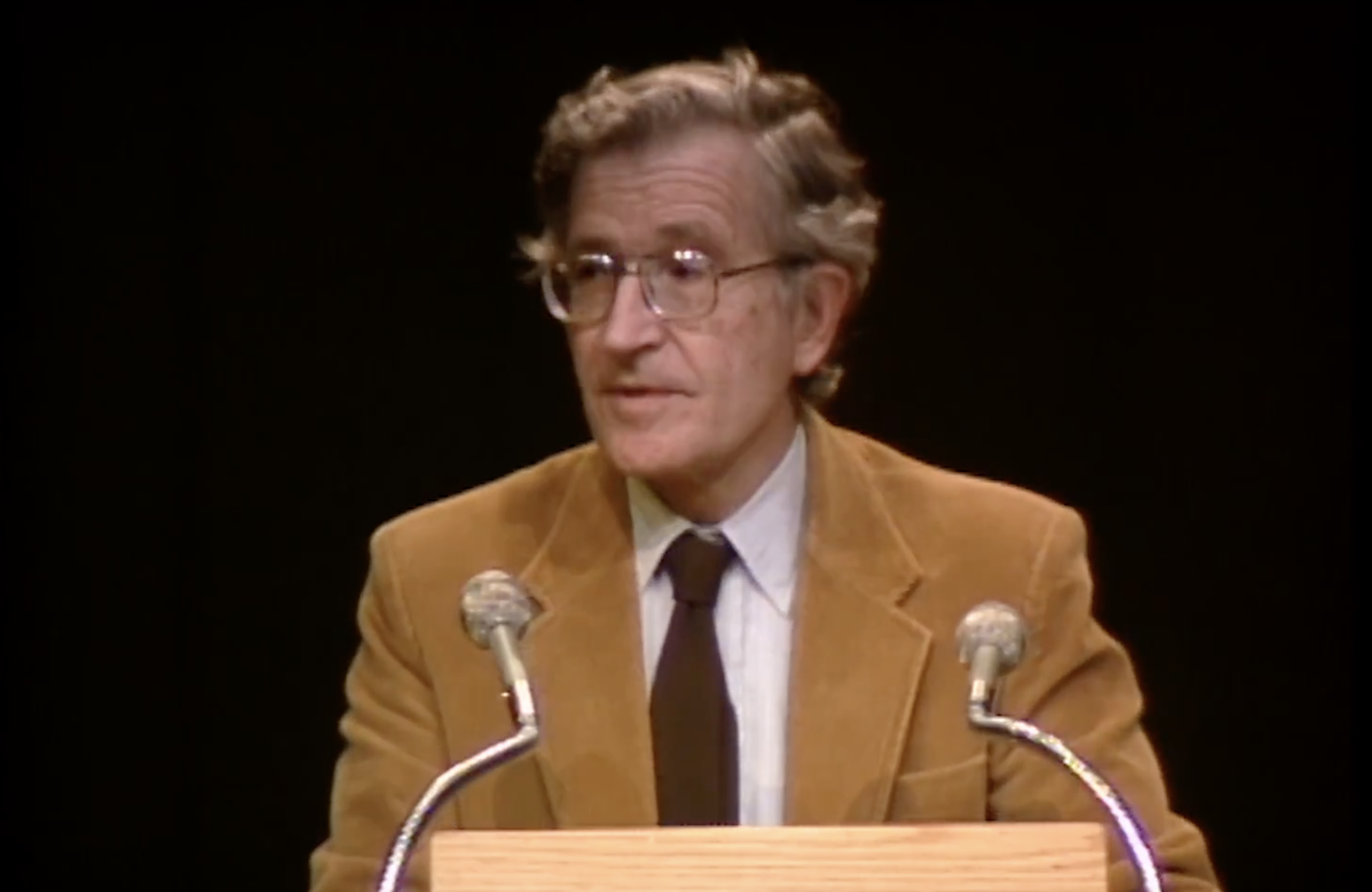

MOORE: At the risk of repeating myself, I'm Gary Moore. And this is John Burchard, Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences at MIT. By the way, since we are discussing the city's tonight, maybe we better start out with a definition. What is a city?

BURCHARD: Well, according to Brendan Behan, the playwright, it's a place where you're least likely to get bitten in the rear by a wild sheep. I don't agree with that. A good city, for me, is one where the unexpected can happen.

MOORE: Well, yes, but most cities I've seen, the only thing unexpected is finding a place to park. What can we do about it?

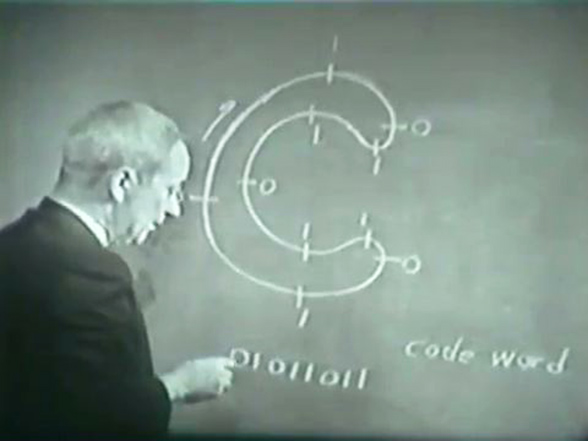

BURCHARD: Well, a lot can be done. But it's the old story of the lag between our technical knowledge of what we do with it. If we could reduce that lag, the world of 1980 could stagger the imagination.

MOORE: Well, if we don't, I can see the day when suddenly everything comes to a halt. Traffic can't move all. The ultimate traffic jam. People abandon their cars on the street. And our city is tied up for good. Only thing to do then is to take a brigade of bulldozers and start over from scratch.

BURCHARD: You mean like this?

MOORE: Like this? What's that?

BURCHARD: Scratch. A clean sheet of paper. That's how they just build Brasilia, the new capital of Brazil, from scratch.

MOORE: What a wonderful idea. It sounds like the perfect answer.

BURCHARD: Well, maybe it is for Brazil.

MOORE: Why Brazil?

BURCHARD: Well, here's a country with 80% of the people crowded on this coastline. An enormous country with a huge and a rich interior. But it had never been developed.

To exploit its great untapped resources, it had to be inhabited. They thought the substitute for our covered wagon was a major city. And they talked about building one, talked about it, for over a century.

MOORE: Well, I understand they finally got it in less than five years.

BURCHARD: Yes. President Juscelino Kubitschek wanted it built before his term of office expired. The site, about 900 miles inland on a high plateau. Temperate climate. Good water supply.

Brazil's great designer Lucio Costa won the competition for the new city plan. That's Brasilia rising in the background. Brasilia was planned as a new capital city.

The buildings have dominated are and will be those of government. The saucers, the House of Representatives. They say it's a big wastebasket, where they toss the bills sent over from the Senate.

That's the Senate under the dome. You see, Brasilia is more than a city. It's a symbol too, a symbol of Brazil's emerging greatness, casting a shadow across the land.

MOORE: All this in just five years. That's really instant city.

BURCHARD: Of course, Brasilia isn't built yet. As a matter of fact, the dust from construction is the most striking feature of living there at the moment. And the red dust everywhere, except when it rains, then it's red mud. It's pretty rough living.

But if you want something badly enough, and the [? Brasilienses ?] do, discomfort's a small price to pay. Brasilia has had to start functioning before it's been finished. Even an instant city isn't part out of a test tube. But these people will hold the speed record for a long time.

Rather than wait for more heavy equipment, they work with their hands. And around the clock too. As a construction project alone, the Brazilians feel that their city outstrips the pyramids and is considerably more worthwhile. They were a monument to death. Brasilia is a symbol of bursting into tomorrow from yesterday.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BURCHARD: They didn't move 45 million cubic meters of red earth with just a pick and shovel of course. When they get through with this grading, every street in Brasilia will be an expressway. Underpasses will eliminate all intersections.

MOORE: No traffic lights. No stop signs. Now, there's a real dream city.

BURCHARD: Things are moving at incredible pace. Only three floors of the hospital are finished, but it's open for business. That's President Kubitschek. He dedicated this and another building on the same day.

This is a dedication of one of the new ministry buildings. Everything on a timetable. It has to be. It's 900 long and rough truck miles back to the old capital at Rio.

Yet no sooner is a building dedicated, then the furniture starts arriving.

MOORE: And these spools of red tape.

BURCHARD: They probably will come later. There's almost no red tape when it comes to speaking Brasilia's construction. This dedication is at the city's only high school. There's no need yet for another because almost the entire school population of Brasilia is of elementary school age.

MOORE: Will, it must be a great place for little kids. Gee, in a whole city, it seems to be one big sand pile.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BURCHARD: You see, even the small fry have caught the architectural spirit of Brasilia. Brasilia is a monumental city. It is a monument to one man, Juscelino Kubitschek, who built it as a campaign promise.

His critics said he was Moses in reverse, bleeding his people into the wilderness.

MOORE: Well, wilderness maybe. But that is certainly no lean to.

BURCHARD: Of course, it's no wilderness anymore. That's the Presidential Palace and his private chapel. They call it the Palace of Dawn.

Not everyone liked it at first. Now they say these statues are Kubitschek's critics, pulling their hair out by the roots.

MOORE: Well, I can see how it'd be a nice place to visit. But does everyone like to live in a monument?

BURCHARD: Well, if you work for the government, you have to live there. One reason Brasilia is possible at all is because it is a new capital. It's one-business city.

You can see this unity in its architecture. Those arrowhead columns are on the executive buildings. And the Supreme Court, they call them Kubitschek's cardiogram.

MOORE: He looks pretty healthy, doesn't he?

BURCHARD: Well, he is responsible for a new world capital, at least for building it. The nations of the world are all represented here.

MOORE: The diplomats seem somewhat reluctant to leave Rio.

BURCHARD: There's a popular song on the old capital that goes I'd rather die in Rio than live in Brasilia. Not sung here I might add.

This is the cathedral. It's build underground with only its crown-like spire showing. That ensures that the skyline will always be dominated by the government buildings.

You know, the critics of Brasilia call it a three-dimensional postcard.

MOORE: Yes, but I can see that the people are proud of it.

BURCHARD: Yes, they also have a song. It boasts that this is a youthful capital of a smiling future, the handsomest city in the world.

MOORE: Where are we now? Is this the wrong side of the tracks?

BURCHARD: Well, strangely enough, Brasilia had its slum before it had its city. They had to build this shanty town to house 60,000 construction workers. To attract workers from all over Brazil, this community has no taxes. They call it the free city.

MOORE: Well, I can see that the kids run pretty free.

BURCHARD: You see, everything's built of wood. They had planned to burn it after four years, but now they're beginning to pave the streets. Somehow these temporary boomtowns have a way of becoming permanent, like our own Gold Rush towns.

And they have the same vitality too. Anyway, it's quite a contrast with the housing in Brasilia proper. Each of these super blocks is designed as a self-contained village. And most of Brasilia will live in them.

Each will have its own supermarket and school and chapel, even its own movie.

MOORE: Are all the apartments alike?

BURCHARD: Well, not quite. But in a one-industry city, everything tends to be pretty similar. It won't always be that way if Brasilia's plan is carried to completion.

There'll be four satellite cities then. One will be permitted industry. When you look out the window, you won't see smoke. No smokestacks are allowed.

MOORE: Well, I'd sure go for that.

BURCHARD: Now, here's a somewhat more typical apartment.

MOORE: It has a certain look of sameness.

BURCHARD: Well, as I've said, this is a one-industry town, government. Same general tastes and interests. That's a drawback.

To be exciting, a city ought to have all kinds of people, rubbing together, giving off sparks, generating ideas.

MOORE: Not exactly a kitchen of tomorrow, is it?

BURCHARD: No, but it's clean. And the plumbing works. So will the window if he unlocks it.

MOORE: The whole city was designed by one man, wasn't it?

BURCHARD: Yes, a Brazilian architect, Oscar Niemeyer. And nothing can be built that isn't compatible with his style, from the President's Balance to corner stores. At least not without an Act of Congress. Only one supermarket was open for the entire complex of super blocks when these pictures were made.

MOORE: The kids I see are learning what is meant by self-service. Brasilia doesn't seem to have any old people.

BURCHARD: That's another drawback to the instantaneous city. Pioneers do tend to be young. Brasilia is a city dedicated to youth.

MOORE: That's certainly lucky. I haven't seen many cars. It looks to me as though everyone has to walk everywhere.

BURCHARD: The people of Brazilian seem willing to pay the price of magnificent distances taking seat. The city's architecture and the space between it is scaled for the fast moving car.

Its streets are express highways. And yet, its public transportation is still meager and primitive. Most of its future population of half a million will always use public transportation.

People in a hurry always have to do a lot of waiting. The people of Brasilia say, we've got our city of tomorrow today. We're just waiting for the paint to dry. And wait they must until the city's built. They even have to wait to go to church.

But they have a purpose. Kubitshek said we have turned our back on the sea and penetrated to the heartland of the nation, now the people realize their strength.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOORE: Well, I'm impressed. That looks like the best thing in cities since Shangri-La. Are we going to have something like it?

BURCHARD: We could, if we want it. As I said earlier, by 1980, half America's population will be living in cities and towns that don't even exist today. They'll have to be built from scratch on land as raw as Brasilia's was. But they won't be national capitals. And we can't copy Brasilia.

Also, the other half lives in old cities that are falling apart.

MOORE: Well, what do we do? Do we walk away from our present cities, make ghost towns out them? Do we move them or tear them down?

BURCHARD: No, we've got too much invested in them to tear them down or to abandon them, architecture, real estate, tradition. What would you build in place of the Alamo? And then there's geography. How do you move the Golden Gate?

MOORE: Well, that's fine. But in one way or another, all of our cities are coming apart at the seams. Brasilia at least had a plan.

BURCHARD: So did we.

MOORE: What happened?

BURCHARD: Oh, the same that could happen to Brasilia. If for the next 300 years it acquires some of the problems that Philadelphia, for instance, picked up in the last 300. Now, this was our first planned city, designed for William Penn in 1683.

A pretty darn good one too. A green country town Penn called it. A holy experiment between two rivers, the Delaware and the Schuylkill. Like Brasilia, it was our symbol of emerging greatness. Well, you know what happened. After nearly 300 years, the city had become a laughingstock.

MOORE: Oh, well, now you're all my streak. Because I couldn't remember when every cornball comic in the business at two things, he had a straw hat and he had a whole file of jokes about Philadelphia, PU. You remember how they all went.

[LAUGHING]

[SINGING]

[INAUDIBLE] There'll be hot time in the old town tonight.

[LAUGHING]

COMIC 1: Hey, daddy, you know what first prize of tonight's bag is?

COMIC 2: No, what is first prize in the bag night tonight, Pat?

COMIC 1: One week in Philadelphia. One week-- But do you know what second prize is?

COMIC 2: No, what's the second prize, Pat?

COMIC 1: Two weeks in Philadelphia.

[LAUGHING]

COMIC 1: Two weeks--

COMIC 2: You're killing me, Pat.

COMIC 1: Philadelphia. That's four as long with lice.

COMIC 2: Hey, Pat, tell me something. If Philadelphia's such a slow berg, how come you're spending your vacation there?

COMIC 1: Well, I'll tell you then. You see, I only got one week. And I thought if I spent it in Philadelphia, it would seem longer.

[LAUGHING]

BURCHARD: It is jokes like that, Mr. Moore, than almost killed Philadelphia.

MOORE: Dean Burchard, they didn't do vaudeville any good either.

NARRATOR: What saved Philadelphia, though it didn't have vaudeville much, in just a moment.

MOORE: Well, Dean Burchard, obviously the jokes didn't kill Philadelphia. What did happen?

BURCHARD: A super plan.

MOORE: Yeah, but Americans don't take much to super planning, Dean Burchard.

BURCHARD: Oh, I don't know. What about our Constitution? That was a super plan with plenty of room for individual freedom in it.

MOORE: Can we have our individuality and plan cities too?

BURCHARD: Yes, provided the plans aren't all alike. No one man, not even Brasilia's Niemeyer can be sensitive to all tastes. If a suit goes out of style or wears out, you fix it up or you get a new one.

But there's a tailor in there somewhere. Somebody has to plan your suit.

MOORE: I see. Then in other words, a city needn't be a uniform or a straitjacket but it has got to be planned to fit.

BURCHARD: That's right. As a matter of fact, it's already going on, Seattle, Kansas City, Tulsa, Detroit, Philadelphia, for instance, had gotten pretty threadbare and are being tailored to make a new life for themselves.

And here's someone who can tell you. This is Edmund Bacon, Executive Director of city planning for the City of Philadelphia.

MOORE: Mr. Bacon, nice to know you.

BACON: Very good to see you, Mr. Moore. Thank you.

BURCHARD: All right, Ed, how do you go about revitalizing an old city?

BACON: Well, I think it's quite simple. You have to have a strong, vigorous plan and democratic action. But you've also got to have the things that we have in Philadelphia, a citizenry that's deeply committed to the idea of a better city, strong business leadership, you have to have a progressive city council.

And you have to have a city administration with a forward looking leader, like Mayor Dilworth. I admit this may sound like a 4th of July speech.

MOORE: Well, I thought I heard the faint sound of gunfire at Bunker Hill. Did you have to do much fighting?

BACON: Of course we did. That's always part of it. Getting a city planning commission is relatively easy. It's the committing of the people and the political leadership to back it that is the thing that is the difficult part of it.

We couldn't have done a thing without the city charter, which was adopted after a very real fight and laid the foundation for the whole thing. But our plan is based on a continuing operation, which can readjust itself to the need of the future generations. In fact, the children in school learn about it in the elementary grades.

TEACHER: Penn laid out four parks or squares. And when you travel around the city, you've been passed those parks many times. I just wonder if there's somebody that knows the names of those four squares. Michael.

MICHAEL: The four squares are Franklin Square, Washington Square, Rittenhouse Square, and Logan Square.

BACON: And when these youngsters are of voting age, they'll have a pretty good idea of the kind of city they want.

BURCHARD: They'll have a pretty darn good plan too, Ed.

BACON: Well, we do think so. But William Penn gave us a very good start. You know what happened, the kind of things that you were joking about-- Mr. Moore was joking abour-- blight descends on us, the railroad penetrates right into the heart of the city on an elevated ugly railroad track called the Chinese Wall.

Traffic congestion, marginal industries. Then at the end of World War II, we realized that we had to do something to revitalize the center to make it more available, to make it a better place in which to do business, and in which to live. If we didn't, there was real danger that Philadelphia, the third largest city in the country, would die.

It's the same problem in all American cities. We already had Fairmount Park, the largest city park in the world. And we decided to run an expressway through it right into the heart of the downtown area.

BURCHARD: Without having to drive passed paperbox factories and billboards and Happy Herman's Used Hubcap Center.

BACON: What you see outside of every city. This was all removed from this area through the redevelopment process. The blight is gone. And in its place have risen four handsome towers, Park Towne Place.

They mark an entrance gateway to the center of the city and affirm the concept of return to center city living. And you remember the Chinese Wall? The Pennsylvania Railroad voluntarily tore it down and in close cooperation with enterprise, private enterprise, developed on it Penn Center, the largest open area for offices in any American business district.

Fresh air, sunlight, and landscaped promenades give a structural form to the whole architectural scheme.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BACON: And below the street, buses, subways, and commuter railroads enter into the very heart of the city, providing a fine and handsome entrance into a pedestrian super block extending under the street and punctuated at various points by gardens and open spaces open to the sky.

BURCHARD: Ed, this sounds pretty fine for you Philadelphians. But what is your plan due to the part of the city that belongs to all the rest of us? I mean, starting with Independence Hall, you people are stewards of a lot of American heirlooms.

MOORE: Don't tell me that you've repaired the Liberty Bell.

BACON: No, it's still quite structurally unsound.

MOORE: Good.

BACON: But I assure you that we are thoroughly conscious of our stewardship. The state is developing Independence Mall to the north. The National Park Service has taken over three blocks of historic buildings next to it. And our city plan is providing a system of greenways and walkways to connect up the landmarks.

The area along the Delaware waterfront was given priority in our plans. It had become a great eyesore. It was dominated by a large and very unsanitary produce market, which no longer needed to be in the center of the city.

It attracted 15,000 trucks a day and caused terrible traffic jams. The Redevelopment Authority cleared all 30 acres. And we built a large food distribution center completely outside the area.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BACON: Next to the waterfront is a section called Society Hill, not perhaps as high-toned as it sounds. The matter of fact is that it was one of the most rundown parts of the city and typical of sick neighborhoods everywhere.

As its values went down, people and businesses abandoned it for other parts of the city and for other cities. But there was something here that was really worth saving. And conventional slum clearance would have been vandalism.

Selective demolition weeded out only the unsalvageable buildings. There were hidden values here that when saved would make this a unique neighborhood in America. Emerging from the decay and the rubble were priceless pieces of America's heritage.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BACON: Block after block of 18th century houses, once they'd been rehabilitated, would become the greatest treasury of colonial architecture in the country. The Redevelopment Authority required all the homeowners to restore the outside of their properties to something resembling its original appearance.

Pride alone compelled them to fix up the inside. And we found improvement spreads. It can be just as infectious as slums. With no prompting at all, neighboring areas started to do the same thing.

And the movement back into the heart of the city was given tremendous impetus. Of course, when you see it all done so neatly, it looks easy. But I assure you, it isn't.

This isn't an instant city like Brasilia. We're bound to step on people's toes. And the people who are hurt have the right to holler.

In fact, this is an inalienable right, which was firmly established here in Philadelphia a good many years ago. This is where the democratic process comes in. Now, I want to give you an example.

And for background, I want to say that in Society Hill the streets were originally designed for stagecoaches and sedan chairs. But with a modern vehicle, the planning commission realized that it was necessary to establish off street parking spaces to make the whole plan work.

The planning commission felt that six houses should be demolished to provide adequate off street parking. And to guarantee the neighborhoods residential character, they wanted seven neighborhood stores to relocate in a convenient shopping center.

And if you think Americans haven't got a voice in city planning, just listen.

BARBER: My pop came here 50 years ago. And I was born in this building 44 years ago. I was married out of this building. I raised three children from this building.

After a person like myself spends 44 years of my life in one house, to have someone come over and to deprive me of my right to earn a living down here, I just don't size things up like this. I don't think it's fair treatment.

WOMAN: To the whole idea of the plan is so important to the whole City of Philadelphia that it is worth it in the whole to have a few people inconvenienced in order to bring alive and to revitalize a whole city.

MAN: Everything in this neighborhood has changed to the best. And I think it's going to turn out to be one of the nicest cities in the country.

WOMAN: We were first married 10 years ago. And we start out the small business in this block for the last 10 years. And then we've been trying to buy this house by working very hard. And we have three children.

The children are very used to this neighborhood. They are attending schools. And we would love to stay here, not to give up our home, which we had to get it in a very hard way.

WOMAN: Benjamin Franklin lived Society Hill. And he had his little printing shop underneath where he lived. And I don't think the neighbors then complained of having a printing shop next door to them.

I think it's wonderful to have all the shops near you, especially when you're an old lady like me. I can't be running away to shopping centers six blocks away on rainy days. And they won't deliver and they won't give service.

I hate shopping centers and I hate supermarkets.

WOMAN: A housewive's dream today is for a centralized shopping center, where she can go and in two hours complete all her shopping for the week and forget about it. As it is now in Society Hill, one place there's a grocery store, another place a laundry, another place a vegetable store, another place a bakery. And by the time you done going two block here and three blocks there and two blocks the other way, it can take you at least five hours and a good pair of legs to do all your shopping.

MAN: Well, I'm very much in favor of the plan. My family and I've staked everything on it. We came down here about two years ago, 2.5 years ago because we were just married. And we didn't have the money to afford a decent home out in the suburbs, I guess.

But we were able to pick up an old place down here for about $7,000. It was a tenement, pretty run down, but basically a fine building. I sometimes say that the only two things I know of that are improving in this world are my baby daughter and the area I live in.

MAN: First of all, I have my whole life invested in this neighborhood. Business was left to me when my dad died. I had to support my mother, sister, brother. In 1948, I finally was able to buy this buildings, where I'm at.

And I struggled very hard to pay the mortgage on it. And finally in '58, I was through with the mortgage. And I felt a little more secure. I've been working all my life for that to try to make my middle age years a little more secure than what I had it before.

WOMAN: I chose to live in Society Hill above any place in the world because of its great convenience, because of the wonderful neighborhood stores. And Harry Altman, I think, renders a great public service. He not only cleans my clothes beautifully, does all my laundry, washes sheets and underwear, everything, washes things beautifully.

And he's just a pickup, they go on to other places. But he cashes check for me. If I say my heels are rundown, where's the cobbler. He'll say I'll take the cobblers for you. Or I run out of bread and he loans me a loaf of bread. Just anything, he's magnificent neighbor. And I'm very proud to have him for a next door neighbor.

BACON: And then the Society Hill Area Residents Association, it's called SHARA, met to decide which faction to support.

MAN: So I think it might be appropriate at this time for me to introduce to you Mr. Aaron Levine, who is Executive Director of the Citizens' Council on City Planning. And I'm wondering, Aaron, if you wouldn't comment on the technical aspects of this Addison Street problem.

LEVINE: Yes. And I'm would be very glad to. I want to mention, first of all, if I may, that the Citizens' Council is interested in the overall viewpoint of the problem. That's the reason I'm here tonight.

Redevelopment Authority in the City of Philadelphia is trying to make the area completely residential. Why do you think that your stores should be permitted to remain?

MAN: I've invested my wife on that home. You people came in and invested money. And they want to see that money secure. They don't are about my livelihood.

They don't care whether I make a living or not, whether I get out of neighborhood or not. I don't think that's fair at all.

MAN: It's the sense, I think, of the-- the sentiment of SHARA that we regard these small businessmen as a necessity, as an extra convenience to this community of homes. And we think that because these people have been here for so many years, owning their own property and conducting their business that they deserve a special consideration.

BACON: Then the Director of the Citizens' Council on City Planning, who had attended the SHARA meeting, reported his group. They are mostly businessmen who give up their lunch hours to attend these meetings. They represent 150 civic organizations, including SHARA, supporting the city plan.

They considered whether to ask the authority for exceptions.

NARRATOR: Member Organization of Citizens' Council has asked us to support them in modifying that plan that we approve previously. They would like to have retained in the neighborhood seven of the local stores. These are stores that are owned and operated by the present occupants.

They're a barber shop, a real estate office, a laundry pickup, drugstore, tailoring shop. There are seven shops. The problem that we face now is, should we recommend amendment of the plan that we previously approved or should we support the original plan?

BACON: Finally, it's in the City Council where the decisions are ultimately made as to what the city is going to be like.

MAN: Be permitted to remain. And that they be permitted to rehabilitate the properties according to the architectural standards of redevelopment of property. The Citizens' Council does not believe that that will have or need have a deteriorating effect on the residential character of the area because, in this case, the aesthetic appearance of those commercial properties can be controlled.

And might we also point out that the inclusion of a few isolated stores, convenient stores in that neighborhood, we believe that this retention of the stores will not disrupt the overall redevelopment plan. And we notice, also, that many of the residents are against the retention of the stores.

But we also note that many more seem to be for the retention of the stores. In summary, we want to recommend that the plan be amended to permit the seven resident owner merchants to be permitted to stay.

BACON: This meeting was concerned not only with the displaced merchants but with the houses to be removed for the parking areas.

WOMAN: I'm not much at public speaking, gentlemen. I am Mildred Fusco Salvo. I am the parent of four daughters, four daughters and a son. They say a mother's happiness comes from her children when they are toddlers.

Well, I never was that fortunate to have that happiness because I went out to work in a meat packing house, 18 below. I went with that purpose to help my husband, to lift the burden, to help payoff the mortgage at 412.

Well, last year, we finally reached that gold. And then our bridges came tumbling down when all this redevelopment came along. To think that I have to uproot my family. And I heard something about relocation.

Someone mention a project. Well, I think it's unconstitutional. Maybe that's the wrong word. Well, I think that's the right word for how I feel to have to put my children in a project, which I heard we would have to go.

We had to deprive ourselves and my children of many little luxuries because, as you know, down the waterfront, it's very hard work and you work when the ships come in. And I don't think a tourist with any humane feelings would appreciate a garden or would want to park their car if they knew the knowledge that a family had to be uprooted.

I'm very nervous. That's all I can say. That's how I feel.

MAN: Mrs. Salvo, would you have any objections to remodel your home according to the Authority?

WOMAN: No, we've been looking forward to all this. Because, Mr. D'Ortona, when we moved in this home, the floors were termite in the joist. And we had a coal stove for almost two years until we were able to put oil heat in.

That was the reason I went to work. And it took all these years to do it. And we finally reached a goal when we paid off the mortgage about six months ago.

MAN: But you would be willing to conform to the Authority?

WOMAN: I'd even go back to work for it.

MAN: You would go back to work for it--

WOMAN: Yes, sir.

MAN: --just to live there?

WOMAN: I'm in the local 195 for 19 years.

MAN: Thank you very much. Call your next witness.

MAN: I would like my mother, mother to come up. I'd like my mother to say a few words. And she would find it a lot easier to speak in Polish. And I would be only too glad to translate it for you. All right, mom.

WOMAN: [SPEAKING POLISH]

BACON: After Mrs. Winolista had made her statement against relocation, she raises a personal matter. Committee Chairman [INAUDIBLE]

MAN: She was there was conditions were very, very difficult. And now they want her to move. She had made inquiries as to repairing the house. And they told her that she would repair it and to repair it. And evidently Mrs. Winolista made this statement, I must bring it out too that her husband had died. But they were up to see me. I don't remember when.

WOMAN: Well, yes, was 28 years for you examiners.

MAN: 28 years.

WOMAN: Yeah. After my husband had gone--

MAN: I don't remember that far back. However, and they had asked me to do something for them. And I did not do it. Well, as I said before, I don't remember what request you had.

But I'm sure that the Committee sitting here today will certainly consider your testimony. And it's certainly nice that you had came here with your son to testify on behalf of the people.

MAN: Mr. Chairman--

MAN: Councilman D'Ortona.

MAN: I want to say this that the whole question comes that arises here is a hardship on a people who worship their home for many, many years. It's a question of them moving out to be rehabilitated somewhere else. They go into a new home in a different section that they never lived there before. They have to go out to make new friends.

The thing that we're interested would this have to be absolutely necessary for those properties to go down before I would go for anything of that sort. If it's absolutely necessary, is one thing. If it's not absolutely necessary, then it's not.

[APPLAUSE]

MOORE: Well, tells us, Mr. Bacon, who finally won?

BACON: I wish I knew. The jury is still out. But I know this, Mr. Moore, you can change and amend and make exceptions to the plan until it's no longer a plan. The price of progress, even in a democracy, is that a few people can get hurt.

The price of standing still is that everybody gets hurt. Please understand, no one gets kicked out on the street. All these people and businesses are to be relocated not exiled 900 miles out into the wilderness.

And the one thing I do know that in the end, the plan will get done. It will win. And it will be built.

MOORE: Well, since there is a price to pay, I would hope that there is progress too.

BACON: Oh, indeed there is. That 30 acre vacant lot you saw will soon look like this. Tall apartment towers and modern townhouses will fit in with the colonial village next to it. A greenbelt along the Delaware River and the yacht mason in place of all the old wards.

But plans will grow way beyond 1980. But by then, we think that William Penn might again recognize his green country town. We think we will have succeeded in realizing his holy experiment.

MOORE: Well, would you say that's going to be better than Brasilia?

BACON: Well, I think this is a place where I'd better leave. Architect Louis Kahn, who teaches the University of Pennsylvania, can be much more objective about this question than I can.

KAHN: It's more difficult to build in our form of society because we must satisfy many interests. In the case of Brasilia, I'm sure the interest is very concentrated and is much more easily controlled. But the wonder that can come out of that great sense of order we may obtain by finding the proper shapes and dimensions and forms out of the complexity of our democratic ways, those forms are more likely to last, in my opinion, over a greater period of time once they are found than those forms, which are concocted and made quickly at a single moment in time.

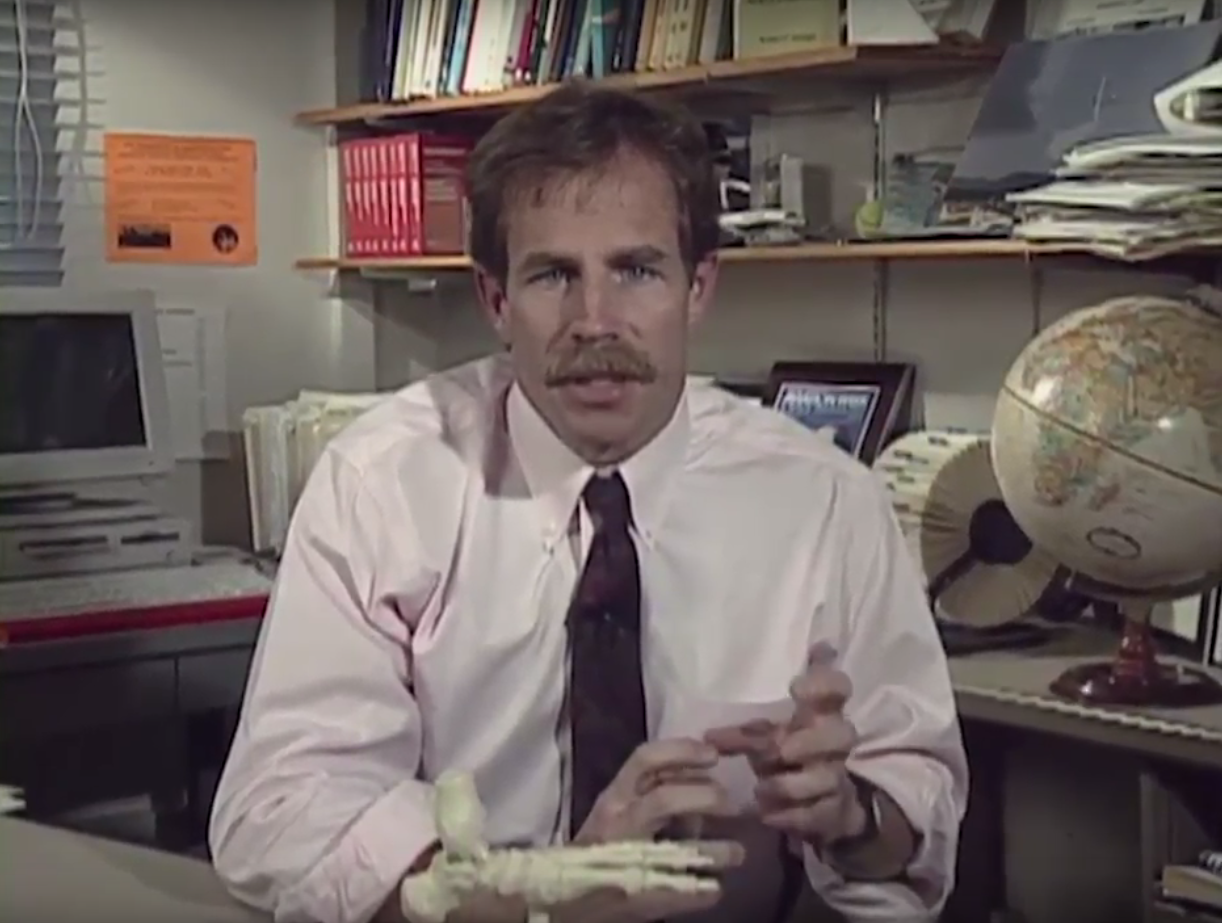

BURCHARD: Of course, Mr. Moore, the choice isn't just between Brasilia and Philadelphia. Architects all over the world have been making schemes, big ones, little ones, crazy ones, very sensible ones. And I'd like you meet Pietro Belluschi, who's Dean our School of Architecture at MIT. Mr.Moore.

MOORE: Dean Belluschi, how are you?

BELLUSCHI: Very well, thank you. Since we've been talking about Philadelphia and showing Professor Kahn, we might just as well begin with his concept for a center city.

MOORE: This is it?

BELLUSCHI: This is it.

MOORE: I must say I couldn't be more surprised. Rather than a future city, it looks quite medieval.

BELLUSCHI: His idea was to provide a ring, a sort of bastions, where the automobile could be stopped. We are protecting, rather than from the enemy, we're protecting from an automobile, which has done as much damage almost as the old enemy used to do to cities.

This is a mile high city, a mile high building. Frank Lloyd Wright designed a few years ago.

BURCHARD: You know, they say he originally brought in a plan for a 52 story building. So then the developer said, well, why not make it a mile high? So Wright said, all right. And he did. I think the story's apocryphal.

BELLUSCHI: Here's a completely different concept.

MOORE: Yeah, sure is different. It looks like a round bridge or possibly a carousel, a merry-go-round.

BELLUSCHI: A whole complex of these bridges could contain a city over a river, for instance, or over the land instead of on it.

MOORE: What disturbs me a little bit about all this is that everything is getting so carefully planned that you're not going to be able do walk willy-nilly. They're planning the building so carefully that there is no room for improvisation or whim on the part of the individual.

BELLUSCHI: Well, that is one of the great dilemmas of modern architecture between the creation of symbols-- and I think the Brasilia is an example of it-- and the way people want to live, which really goes back to the way they done for a century, millennia, that of being close to nature under the trees or close to their mother nature.

But it's well that they are architects who think simply in terms of symbols. Because those are really what makes the human mind and the human being different from animals. Animals can be comfortable in their caves. But only human being can create symbols.

BURCHARD: Do the architects who plan these things live in a city or do they live out in the woods somewhere?

BELLUSCHI: I'm sure they live in the woods.

BURCHARD: That's what I thought.

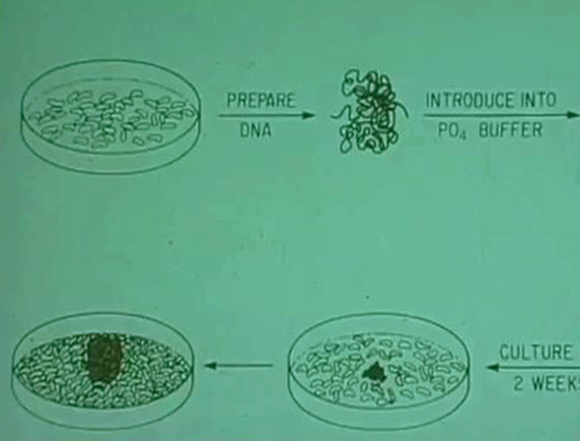

BELLUSCHI: You want something wild again, Mr Moore, here's a city made out of chemicals.

MOORE: It looks like a window of a woman's hat shop. Out of chemicals?

BELLUSCHI: Yes. I suppose the architect read somewhere in the chemical book that you could make powder expand into some predetermined shapes, such as a sphere.

MOORE: You drop this powder in water and poof, you've got instant city. Imagine what a kid could do with a vacant lot and a chemistry set.

BURCHARD: Well, it's fascinating. And I, for one, am always afraid to say that anything is not going to come about or anything is impossible. Because the impossible is being accomplished every day. But this I must say does seem to be a little far out.

BELLUSCHI: Now, we're getting into a little bit more visionary, I would say, forms. Oh, this is a plan for a marine city by a Japanese, name is Kikutake. You can see that they're going into the water and cylinders, which will be lined inside with houses.

MOORE: Well, I must say this kind of appeals to me, the idea of having a picture window underwater to look out in the water at the various life to me would be fascinating. Of course, if you build it in the Long Island Sound, you see nothing but acres and acres of beer cans.

BELLUSCHI: Well, maybe we ought to get back to dry land again. Of course, in American, In United States, we are not short of land. So that we have different problems.

We have a job ahead, which staggers the imagination. But we see the first steps, sound steps, by architectures devoted to their profession. I, for one, believe that the city's going to survive, not only survive but flourish again.

MOORE: Well, you know, we started this program in kind of a dream about 1980. And what we've just seen is so exciting. I wonder whether I'm back in a dream. Is any of this really possible?

BURCHARD: Well, of course, Mr. Moore, it is possible. We certainly have the engineering skills. And of course, we have the resources.

MOORE: Well, in other words, the question then is simply have we the will?

BURCHARD: I think that's right. It's a particular kind of will too. It's a public will. Science doesn't, perhaps, have to have public participation the way this does. And so the problem for the scientist is different.

MOORE: Well, I don't think I would have been much help to Mr. Einstein.

BURCHARD: No, neither would I. And I think perhaps not the physicists, wouldn't have either. But here, we have to face the fact that a presidential decree, for example, could not alone have created Brasilia in five years. Or even the best plan in the world they can make for Philadelphia will alone remake Philadelphia in, say, 50 years.

MOORE: I see.

BELLUSCHI: That's right, Mr. Moore, most of our major cities have plans.

MOORE: But are we going to get them?

BURCHARD: Well, I don't think one can say for certain if this will happen. I don't know how many businessmen are willing to give up lunch hours for important meetings. I don't know how many small people after working all day are going to be willing to give up time for group meetings at night, Citizens' Councils.

I don't know even how many will vote for responsible public officials. And then most of all, I think I don't know how many individuals who prize some small, personal thing very much are going to be ready, as they will perhaps have to, to give that up in favor of a larger total thing, which they themselves will enjoy, but which they can't anticipate before it's been done.

MOORE: Well, gentlemen, what concerns me is that if you fellows don't know, who does know? How do we get it? How do we get big city 1980?

BELLUSCHI: It all depends how much you want it.

BURCHARD: That's right. It all depends on how much you want it.

MOORE: Well, thank you, gentleman, both for being with us tonight. It's been most interesting, most informative.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

NARRATOR: Commemorating the Centennial celebration of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Tomorrow was produced by the Public Affairs Department of CBS News.