"Management in the Year 2000"—Lester C. Thurow and Carl Sagan

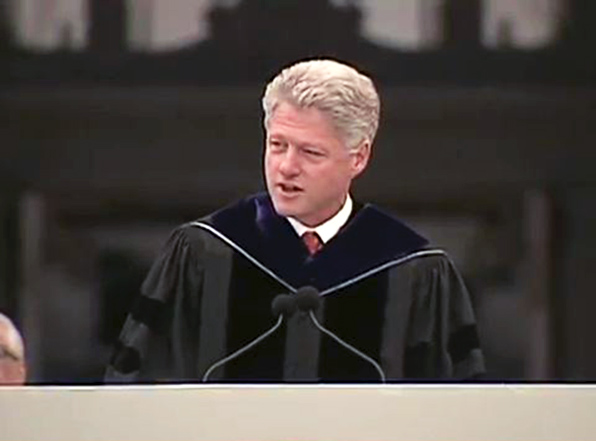

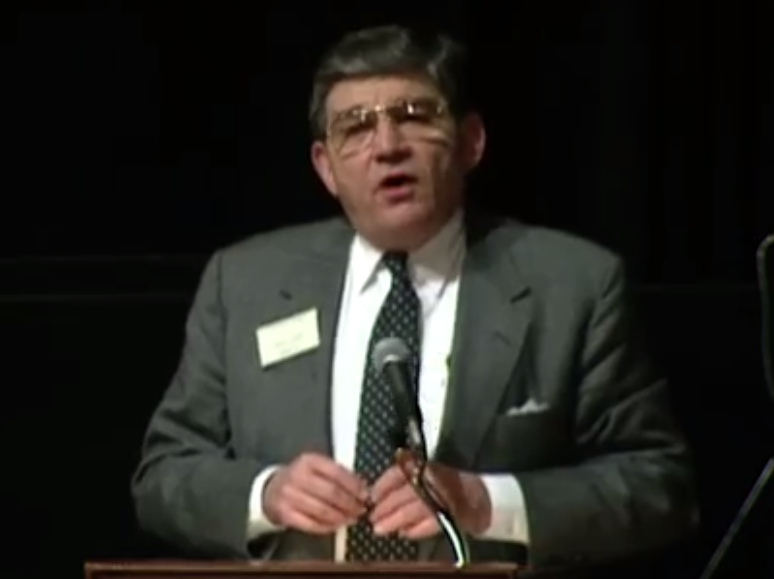

STAR: Hi, I'm Steve Star of the Sloan School. Welcome to our first Senior Executive Program Symposium on Management in the Year 2000. This year as the faculty tried to plan an appropriate end for the MIT Senior Executive's Program, it occurred to us that with the average age of the seniors being about 45, the end of the century really wasn't so far ahead. In fact, the year 2000, just 13 years from now, would probably represent the point in time where the students in this program are, in fact, at the very height of their careers. After a tough, long, hard, intense nine-week program, it seemed fitting, therefore, to kind of think toward the future and ask not so much where we've been or where we are, but, in fact, what is the world going to look like in the year 2000 and what will be required of managers in that period.

Now, obviously this is a very large task. And it's something we're planning to spend several days on following a relatively straightforward model of thinking about the future. Essentially, if we think about time running this way, and we say that right now we're here at the origin, somewhere out here there is an environment. And it's in that environment that our people, as their careers progress, will, in fact, have to be effective managers. The basic notion underlying our symposium is that we need to start by defining what that environment looks like and then to ask ourselves, what is it that as managers we're going to need to do to make our firms and ourselves successful in that environment?

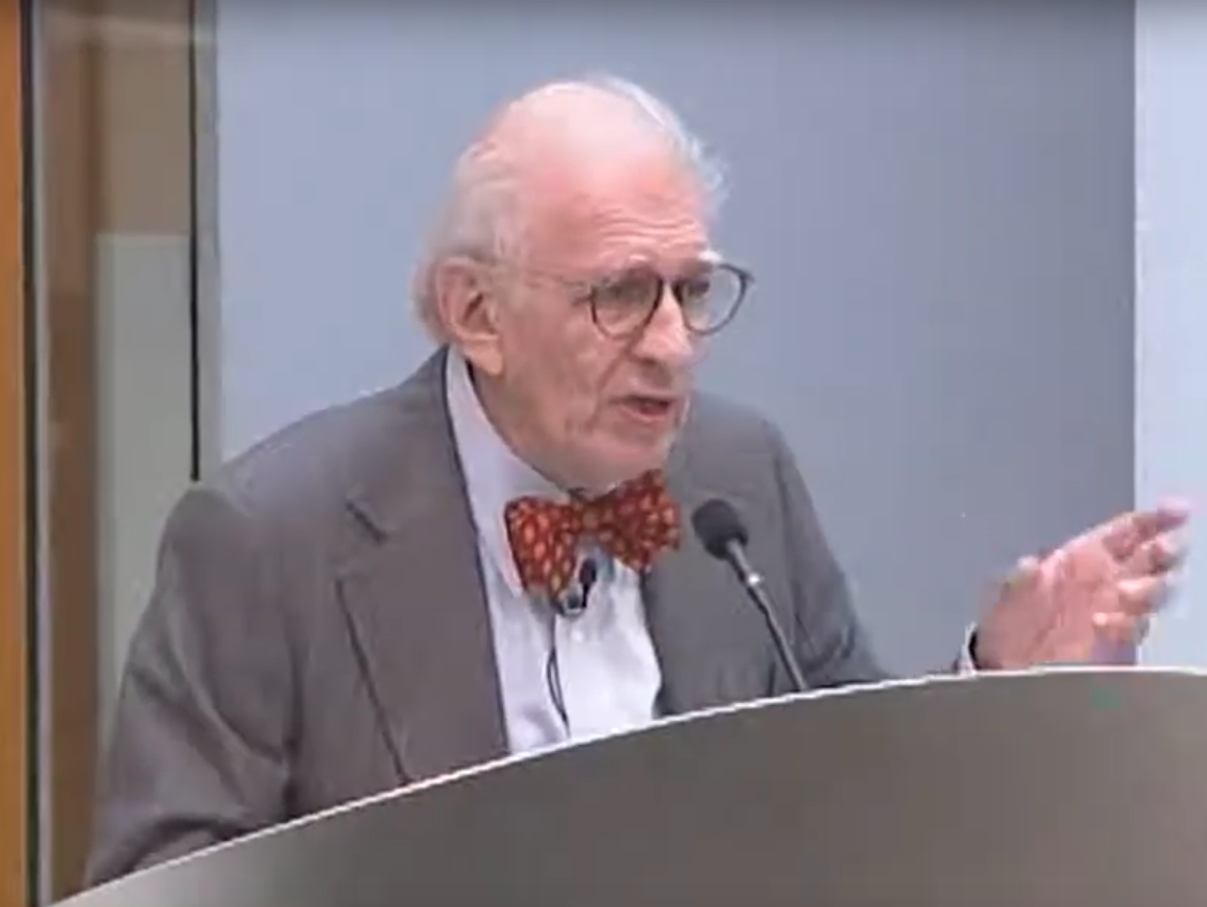

This morning, as our symposium starts, our focus is really on the definition of that environment. We are exceedingly fortunate to have with us two exceptionally distinguished scholars, Carl Sagan from Cornell University, one of the world's most well-known and authoritative scientists, and Lester Thurow, who's recently become dean of the Sloan School, who's one of the world's most esteemed economists. Basically what Carl and Lester are going to do this morning is talk about science, technology, and economics in the year 2000 in order to give us a basis for us then to use, working in small groups, in defining the managerial tasks during that period.

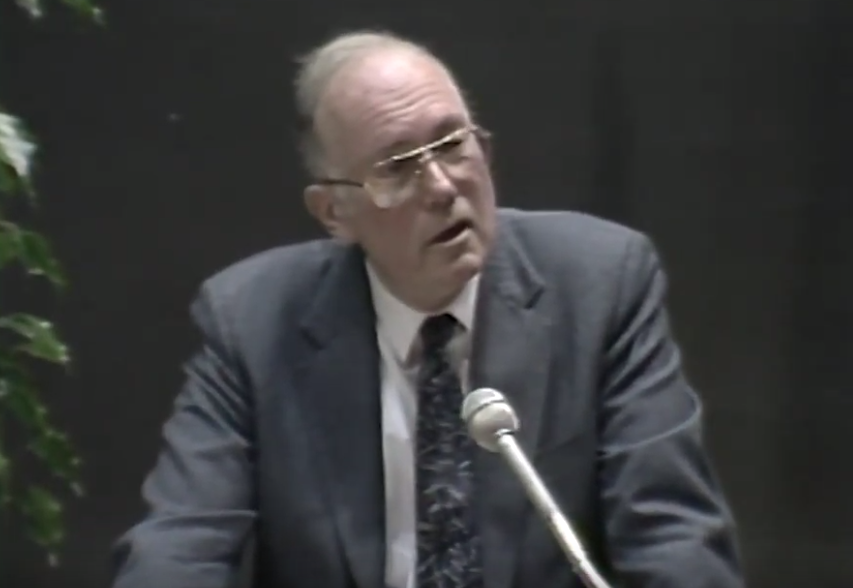

It gives me great pleasure to introduce to you now our first speaker for this morning, Lester Thurow, the new dean of the Sloan School. As you all know, Lester is one of the world's most renowned economists, perhaps best known for his work on The Zero-sum Society and The Zero-sum Solution, both of which argue very, very cogently how difficult it is to make decisions, whether societal or managerial, under the constraints which we as managers all face. Lester, what do you think the world's going to be like in the year 2000?

THUROW: What I want to make an argument today is if you think of this diagram, you've got to start before his axis there. In order to understand the future, you've got to understand where we've come from. Because I think where we've come from has a big impact on where we're going.

What I'm basically going to argue today is that if you look at the world economy, it's essentially come to the end of the road. The world's economy as we know it can't evolve any farther than it has evolved down the road it's now on. And in some sense, we have to build a new road to wherever we're going.

And so once again, if I was using his diagrams, I would have two possible places we could go. And the places we go will depend on what we do. It isn't simply a matter of prediction.

But to make that argument, let me start back in the past. And I basically want to start in 1944. Because in 1944, we had Bretton Woods. And between 1949 and 1953, when we did the GATT, was the period of time when we built all of the institutions that now dominate the world economy. And we set the world economy up as it now exists back in that period of time.

And if you look at that period of time, it's very interesting as to how and what we thought about designing the world economy. There was a tremendous argument at Bretton Woods. One side of the argument argued that the United States and the Allies in World War II should do the standard thing after World War II, the standard thing that has been done at the end of every war in all of human history. And that is you try to permanently destroy the economies of your adversaries. That's why Rome sewed the field of Carthage with salt.

And there was a proposal at Bretton Woods to permanently de-industrialize Germany and Japan. And actually, in Germany for six months we carried out that. Proposal we literally and physically put machine tools on flat cars and pulled them out of Germany. Most of the equipment went to the Soviet Union. But the British, for example, were offered the plans and plants of the Volkswagen corporation. They turned it down because they said it was junk. But they could have had a Volkswagen if they had wanted it.

We never did it in Japan because before we actually literally won the war with Japan, people had a change of heart as to what the strategy should be at the end of World War II. And the strategy is what I'm going to call the naive American strategy. Naive American strategy said if you make countries rich, they will be democratic. And if you hook their richness on the American market-- they have to be rich by dealing with Americanss-- then they will have to be American allies.

And that's where the Marshall Plan came from. And that's where foreign aid came from. If you think about foreign aid, it was very strange. You have to remember before World War II, the concept of foreign aid never existed because the purpose of colonies was to make the home country rich.

There's a big argument as to whether the British got rich because of their colonies. But the British thought they were getting rich because of their colonies. You take gold out of the gold mines of Latin America. You take raw materials out of your colonies.

And there was no concept prior to World War II that it was in your self-interest to make these underdeveloped countries rich. They were supposed to feed the home country-- France, Britain, whomever. And so foreign aid was a brand new thing in 1947 just like the Marshall Plan was a brand new thing.

Now the interesting thing is we offered the Marshall Plan to Marshal Stalin. He turned it down probably because he was the only person the world who thought it might work. But his argument was, we're going to build a socialist world economy. You're going to build a capitalist world economy. And we're going to crush the capitalist world economy.

And, of course, one of the interesting things about Gorbachev is he has officially given up on that Stalin strategy. And the Russians are now applying to join all of these institutions like the IMF, the World Bank, the GATT-- all these things they could have joined back in 1947 and refused to join because they had this strategy of building a socialist world economy.

Now the interesting thing about that naive strategy is if you look at the results, it was the greatest success story in human history. And it grossly exceeded the expectations of even its most avid proponent. Between 1945 and 1980, the world GNP grows faster than it ever has in human history, probably by a factor of three. And with the exception of African countries south of the Sahara, every single country in the world is noticeably wealthier on a per capita basis in 1980 than it was in 1945.

I spent a year working as a development economist in Pakistan in 1972. If you had told me in 1972 that in 1986 India, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, they were all going to feed themselves and not need to import food-- they hadn't done that in 1,000 years-- I would have looked at you as if you were absolutely mad. But, of course, it happened.

And so if you think of that strategy we put in place between 1944 and 1953, it was a tremendous success story. But then if you start to look at things in the 1970s, you see something that's very interesting. In the 1970s, the rate of growth was just half that of the 1960s. We go from a 6+% world rate of growth down to a 3+% world rate of growth.

At that time, people said, well, it's the energy shocks and the inflation, and governments having to fight inflation by slowing down their economies. When the inflation goes away and when the oil shocks go away, the world economy will speed back up to those growth rates of the 1960s.

Well, in the first half of the 1980s, the oil shocks go away. In the first half of the 1980s, the inflation goes away. And the growth rate in the first half of the 1980s is just half that of the 1970s. Instead of speeding up, the world slows down by a factor of two once again.

And then in January 1986, for at least one shipload of oil, the price of oil goes all the way down to $8.50. And the world's financial headlines all say, great news for the industrial world. Economic growth is going to speed up. But in the two years that are in the bag of the second half of the 1980s, the growth rate is just half that of the first half of the 1980s.

And so what we have done is gone from a world that was growing at 6% in the 1960s to a world that's growing substantially less than 1% in the second half of the 1980s. And if you look around the world, you start to see a whole set of problems. And everybody identifies these problems as having different causes. I want to argue it's the same cause. Let me give you some of the problems.

After this tremendous success story in the third world, from 1980 to now, the per capita income in the third world has fallen 15%. So instead of having good growth rates in places like Latin America, South Asia, we're now getting declining per capita GNPs in those countries. If you went to Europe in 1970, you would have seen a 1% unemployment rate. And if you went back to Europe every December for 17 years since then, at the end of every single year, with no exceptions, you would have found a higher unemployment rate at the end of the year than at the beginning of the year. And that's going to be true in December 1987 versus December 1986. And we've now got Europe with official unemployment rates of 13% to 14%. But if you include in the disguised unemployment people on medical disability who shouldn't be there, the Europeans probably have something closer to 20% unemployment.

And if you look in the United States, and you look at the category which the Department of Labor used to call production workers and they now call non-supervisory workers, which is about 2/3 of the American workforce, and you look at their real wage in 1970, and then you looked again at their real hourly wage rate in 1986, you would have found that there are real wage rate in '86 is 7% below where it was in 1970. The United States has never had, in all of American history, a 16-year period of time when real wage rates don't grow for 2/3 of the population. Now family incomes are up because wives are going to work. But hourly incomes are down for a very large fraction of the American population.

And basically if you take any industry you can think of in the world-- semiconductor chips, copper, steel, farm products, you name it-- ask how much of that commodity could the world produce if the capacity that already exists was simply working at capacity, the answer is we can produce from 50% to 100% more of everything that the world has or wants. Now that is a sign of something that has gone fundamentally wrong.

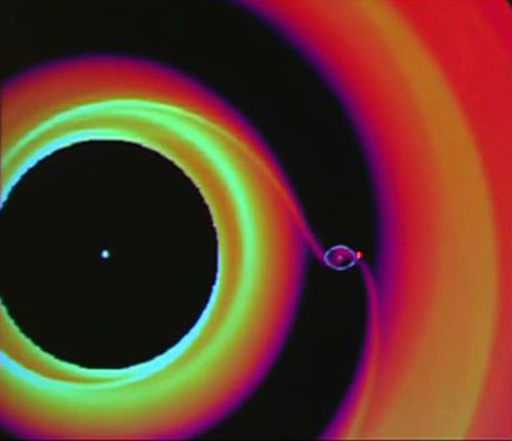

And on top of that, we have put a problem which I'm going to call the economic black hole in the world economy. If you remember your astrophysics, a black hole has two characteristics. And I'm on narrow ice here. I realize that.

SAGAN: You're doing fine so far.

THUROW: The first characteristic is the farther you get into it, the harder it is to get out of it. And eventually not even light can get out of it. And that's why it's a black hole.

Second characteristic is the physics inside the black hole is very different than outside the black hole simply because of the intense pressures of gravity. Well, the black hole in the world economy is the trade deficits or surpluses because they are mirror images of each other. If the United States doesn't have $160 billion trade deficit, Japan can't have a $100 billion trade surplus and Germany can't have a $65 million trade surplus. Eliminating one is eliminating the other. So you can look at it either way.

Now those trade deficits or surpluses are basically like a black hole because they're very rapidly sucking the world into this situation. From the point of view of the rest of the world, the rest of the world has got a standard of living which is now dependent on having an export surplus to the United States. $160 billion worth of goods requires $4 million full-time full-year manufacturing workers at American levels of productivity.

So if the rest of the world has a trade surplus with the United States of $160 billion dollars, since they don't have productivity on average which is as high as the American economy, that means somewhere in the rest of the world there are more than 4 million full-time workers who wouldn't have jobs if the rest of the world couldn't have a trade surplus with the United States.

Let me give you two quick company illustrations of the problem. Take Volvo and Saab. They sell more than half their cars in America. Where could they sell those cars if they couldn't sell them in America? The answer is it's so many cars, they couldn't sell them anywhere. And if the American market was cut off for Volvo and Saab, they would have to shrink by more than 50%.

The most dramatic example is Japanese video recorders. Last year, the Japanese made 38 million video recorders. You know how many they bought? 6 million. You know how many America bought? 22 million. Where could the Japanese sell 22 million video recorders year after year if you couldn't sell them in the United States? Answer's nowhere. And the Japanese video recorder industry would have to shrink by 2/3 with lots of people being laid off.

But we're equally hooked. We're hooked on the trade deficit in the foreign loans. In 1986, one out of every $4 borrowed in America was a foreign dollar. If the foreigners hadn't let us money, one out of every four cars could not have been financed. One out of every four houses could not have been financed. One-fourth of the federal deficit could not have been financed. One out of every four credit cards would have to have been repossessed.

$160 billion dollars is 4% of the American GNP. It essentially means that you and I who are Americans last year got a 4% addition to our standard of living we didn't have to pay for. We borrowed the money. In addition to that, we were allowed to violate what I call the first commandment of a Swiss banker-- never lend money to anybody who has to borrow money to pay interest. We were borrowing money to pay interest, about another 1% of the GNP. And when the lending stops, we'll have to give that percent of the GNP to the rest of the world to pay our interest bill.

And there is something which is probably now not just a technical economics term to you, and so you will recognize it when it hits the newspapers. It's called an adverse shift in the terms of trade. If you balance your balance of payments with the falling value of the dollar, every time you sell something, you get less. And every time you buy something, you pay more. And therefore, in order to improve your balance of payments by 4%, you need a much bigger swing in volumes. And in fact, in order to improve our balance of payments by 4%, the United States will have to give up about 8% of its goods. And so the United States, if the foreign lending stopped, would face an 8% or 9% reduction in its standard of living.

Now that's not the Great Depression, where our standard of living went down 28%. On the other hand, it's not a recession. Because in our biggest recession since World War II, our standard of living has only gone down 2%.

Now what that tremendous imbalance in the world trade has done, it's terribly important in thinking about these things for an economist to make a very clear distinction between what we know and what we don't know. See, in this area, there are two things we don't know and one thing we do-- I mean, two things we do know and one thing we don't know.

First thing we know is no country can run a trade deficit forever, which means no country can run a trade surplus forever. You can't run a trade deficit forever because you have to borrow the money. And you have to pay compound interest on the indebtedness. And no human being has ever whipped compound interest. At some point, the amount of money you have to borrow is bigger than the rest of the world's ability or willingness to lend. And the minute the lending stops, the dollar falls to the level that produces a trade surplus so that we can pay this interest, however low that would happen to be.

Second thing-- and this is where the physics of the black hole comes in-- is if you are a debtor nation-- and the United States is now the largest-- you have to have a trade surplus in the long run because that's the only way you can earn the money to pay the interest to your foreign bankers. On the other hand, if you're the creditor nation-- and Japan is now the largest-- you have to have a trade deficit because the only way they can earn the money to pay your bankers is if they have a trade surplus and give the money back to you.

So today, we have a trade deficit. Japan has a trade surplus. Tomorrow it's going to be exactly the opposite. We're going to have a big trade surplus. They're going to have a big trade deficit.

Now what don't we know? Those two things are not predictions. They're just statements of economic arithmetic. They're absolutely true. The only uncertainty is when. And that is something economists can't tell you.

Because, see, here again, I'm going to use a physical analogy. Economics is like geology. See, geologists can explain earthquakes. It has to do with plate tectonics. But they can't tell you where, when, and how big-- all the interesting questions.

Economics can tell a fundamental story, but we can't tell you when, where, and how big, and the speed of adjustment, which are precisely the things you would like to know. And one of the marks of wisdom that you should take away from this is anytime your company economist tries to tell you when, where, and how big, as opposed to what are the fundamental forces, you ought to be a little skeptical.

Now the question then I want to ask you, or pose for you, why is this happening? Why do we get these tremendous problems that sit around the world, a world that's kind of slowly sunk into stagnation, these tremendously volatile markets, disequilibriums in trade, and all that? My argument to you is it happens not because the world has failed, but precisely because the world has succeeded. That strategy back in 1944, remember, was a strategy of making the rest of the world rich. And it worked. We now got lots of the world that has a per capita GNP approximately equal to that of the United States. And everybody has a per capita GNP much higher than they did back in 1945.

But the institutions in 1945 were built on some assumptions about the world which are no longer true because the strategy was a success. One assumption was the United States is economically very large compared to the rest of the world. 1945, we were 45% of the world GNP. As late as 1960, we were 50% of the world GNP. Today, we're 23%. There are things that United States could do, because it was so big relative to the rest of the world, that it can't do any longer because it's now much smaller relative to the rest the world-- not because we've done bad things, but precisely because we've done good things.

The economy that was built back there assumed capital controls. It assumed money would not flow between countries. We didn't allow money to flow between countries until the late 1960s. And nobody envisioned the world capital market that we now have.

For example, the world capital market has made Alan Greenspan's job obsolete. He thinks he's important. The world thinks he's important. But he's not. Because his job is to control the American money supply. But there ain't any the American money supply. There's a world money supply.

You and I can buy a house in Boston in German marks. We can do a deal in the Bahamas without ever being there, either one of us. We can borrow euro dollars, euro yen, euro marks that have nothing to do with any central bank in the world. We have a world money supply which the world collectively can control, but no country can control its money supply.

The United States when it was powerful could do things that it can no longer do. For example, when the common market was set up in the mid-1950s, all of the evidence showed the United States would be a loser. Our exports would go down when the common market was established. Despite that fact-- and it was true-- we were the biggest advocates of the common market because we said, we're willing to take the economic losses to make Europe into a political union.

When Spain joins the common market 30 years later, we demand a billion dollars worth of reparations on the ground it's going to hurt our exports. And we demand that they pay us that billion dollars that we're going to be hurt because Spain joins the common market. And it's just an illustration of the tremendous change that's occurred in the world economy because of those kind of things.

And nobody in 1945 conceived of the modern telecommunication, computer, multinational company technology where you can put and manage a plant in Seoul, Korea just as easy as you can put and manage a plant on the other side of metropolitan Boston. That was a world that just wasn't conceived of back at that period of time. Multinational companies weren't conceived of back in that period of time.

And what it means is that basically I would argue to you that the world is so different that the institutions that work very well for 30, 40 years have quit working because one of those institutions was the fact that you could, in fact, manage your economies. But what we've done is create a world economy where nobody can manage their economy.

Let me give you a quick illustration. The French, which is the fourth-largest economy in the Western world, discovered in 1982, when they tried to do precisely what Kennedy and Johnson had done in the 1960s and what Ronald Reagan was successfully doing in the United States-- i.e. Stimulating their economy with lower interest rates, lower taxes, more government spending-- it wouldn't work. It worked in the sense that the Frenchmen went out and bought things. French spending, after the Socialists came in and put their policies into effect, actually went up 5% or 6% a year. But 80% of it went into imports. And so it wasn't helping the French economy stimulate production and employment. It was helping the Italians a little bit, the Germans a little bit, the Spanish a little bit, the British a little bit. But it wasn't helping the French.

And if the French can't stimulate their economy, certainly nobody smaller. Because what happened in France is you try and stimulate your economy. You have a balance of payments crisis. Your currency falls. This was a period of the second oil shock, and so inflation goes up because the price of imports goes up. And within a year, the French are back to austerity, i.e. Deflating their economy.

But if France is forced to retreat to austerity, then everybody smaller than France is forced to retreat to austerity. And so if you today look at a country like Ireland or Spain, both of which have 20% unemployments, they're putting in deflation-- deliberately putting in deflationary policies which will make their unemployment higher. And of course, if that happens in most of the countries of the world, the world economy sags into stagnation.

Now I would argue to you that what the United States successfully did in 1983 and '84 is the last gasp of steam in the old economy's boilers. Because what we did in '83 and '84 was what Kennedy and Johnson had done back in '63, '64, and '65-- cut taxes, raise government spending, print money like crazy, and lower interest rates. And it worked. American economy grew almost 10% in '83 and 7% in '84. And we pulled the whole world economy out of a recession. The OECD will tell you that almost 100% of the growth in Europe and Japan in '83 in '84 could be traced to exports to the American market.

And so we were once again the giant economic locomotive providing the market to lift everybody out of the '81 and '82 recession. But we could do it for one last time for one simple reason. In 1982, we started off as the world's largest creditor nation with $152 billion worth of international assets that could be sold, which meant an enormous amount of unused borrowing capacity. Today, we have an international debt of something on the order of $400 billion to $425 billion dollars. So in a relatively short period of time, we've gone from plus 152 to minus 425.

And what it meant was we could provide a consumption market for the rest of the world for one last time. But suppose we had a recession today. Could the United States do it again? Would anybody lend us another $500 billion so that we could put another $500 billion worth of demand into the world economy? And if they would lend it to us, should we borrow it? Because in that sense, we really are mortgaging our future because at some point in the future, we'll have to lower our standard of living, generate those trade surpluses, and pay interest to the rest of the world. But what we've then got is a world economy that doesn't work. Because if we were to fall into a recession now, there would be no mechanism for getting out of it. None whatsoever.

Now so what I want to argue to you is that we've essentially come to the end of the road. And it's like shifting from horse and buggies to automobiles-- a new technology. And I really do think, in many ways, it is a new technology with this telecommunication, computer revolution, and multinational companies and all these new institutions.

But when you shift from horse and buggies to automobiles, you need new roads, new driving regulations. And where the world is now is we need to build a new world economy, which would hopefully work as well as the old world economy, just like we did between '44 and '53. But this time, it's much harder. And what it means is that the United States has got a very schizophrenic foreign economic and military policies because we've never sat down and systematically said to ourselves, the world is going to be different. And rather than just kind of letting it all peter out into stagnation, even though we're going to be a loser, in a political sense it pays to have those conferences and rebuild the world economy.

And, of course, you can't do it without the United States for two reasons. One, we're still twice as big as anybody else in absolute terms. And secondly, the second and third economies are Germany and Japan. And because of the history of World War II, they can't lead on this issue. And by the time you get down to the fourth biggest economy, you're down to France. And it just isn't possible for an economy that small to kind of really play a leadership role in kind of rebuilding the world economy.

Now there are two places I mentioned we can go. See, my argument is we're at the end of the line. I suppose we could simply sit there at the end of the line with the train stalled. I don't think we'll do that. That isn't human nature. If the system doesn't work, we have the tendency to break it up and build something new, even if the something new is worse.

Now there are basically two things we could do. Let me first give you what I will call the economist solution. And this is the solution that has very wide economic support in the economic community all around the world. It's something that has no political support whatsoever.

The argument is that Germany, Japan, and the United States should get together and play the role the United States used to play by itself. Because the three of them together are about 50% of the world GNP. They're just about what the United States used to be in the 1960s when the world economy worked very well.

And so these three people should basically coordinate their economic policies, three countries. And the economists even know what they all should do. What the United States is supposed to do is very rapidly cure its federal budget deficit, either by raising taxes or cutting spending. The rest the world doesn't care. Reduce $200 billion worth of demand for foreign funds. With the United States government out of the world capital markets, real interest rates could come down. And with real interest rates much lower, the world economy would grow faster. With the world economy growing faster, the United States could export more and cure its balance of payments problem, as opposed to the rest of the world having to export less and creating an unemployment problem. And the argument is if the United States would rapidly balance its federal budget, that would make them grow faster, us grow faster, and make the world a better place.

But there's a downside to that. If the United States simply raised taxes by $190 billion dollars, that's taking $190 billion dollars spending out of the world economy, which is 5 million jobs. 3 million of them would be in the United States. 2 million would be abroad. And that's a worldwide recession.

So if you want the United States to have the fiscal policies which balances its budgets, somebody in the world has got to add $190 billion worth of demand at the time the United States is subtracting $190 billion dollars worth of demand. And the argument is that's the role for Germany and Japan.

And in the German case, people go to Germany. I've been in these groups along with a lot of other people. And people say, well, look, Germany has got a 9% unemployment rate and rising, a $65 billion trade surplus, a rate of inflation of -2%, and two out of the last three quarters the growth rate has been negative. If there is ever a country in all of human history that should stimulate its economy and grow faster, it is Germany. And without Germany growing faster, the rest of Europe can't for any prolonged period of time.

And Germany in Europe is a little bit like Godot in the play Waiting for Godot, if you remember that play. Everybody sits around in Europe having very nasty conversations about Godot. When is he going to show up and start growing? And what I mind remind my European friends, if you remember the play Waiting for Godot, at the end of the play, Godot has never showed up. The Germans may never do it.

And then we go to Japan. And we say, well, the Japanese had a brilliant economic strategy after World War II. But it's come to the end of the line because it's been successful. From being a very small country economically, they're now the second largest industrial power in the world. And they run a trade surplus in manufactured products with every country in the world with no exceptions.

The problem is not that Japan doesn't buy from the United States. The problem is Japan doesn't buy from anybody. And the world can't work with the second largest economy in the world running $100 billion trade surplus. That's just taking too much demand out of the rest of the world. And that helps Japan a little bit, but it produces stagnation everywhere else in the world because everybody else in the world has to absorb these trade surpluses coming out of Japan.

Now Japan can't simply stimulate the way the Germans can because they've structured an economy that's essentially built against imports and an economy which is built against domestic demand. And so economists both inside and outside of Japan say what the Japanese need to do is restructure so that they can become a domestically-led economy. There've been two white papers in Japan that agree on what they ought to do. They've got to build a lot of infrastructure like roads because no sense buying a car unless you got a road to drive it on. Japanese have very low car consumption for their income level simply because they have a very poor road structure.

And then you've really got to do something on the housing front. Because first of all, it's absolutely crazy for a country with a per capita income of $17,000 to have less space per person than Korea with a per capita income of $3,000. And Japan is not a crowded country. There are fewer people per square kilometer in Japan than there are in the Netherlands. And the Netherlands has nice housing. There's no excuse in the world as to why Japan can't reorganize itself to build housing.

And if you had more space, then you could buy some consumer durables. They don't sell very many grand pianos in Japan. They build them, but they don't sell them-- not because nobody plays a piano, but nobody's got a place to put a grand piano.

The problem with the economists' strategy, of course, is very simple. It would require Japan, the United States, and Germany all to give up some national economic sovereignty and admit publicly that they don't control their own economies. And when each one of the three is asked to do what I just said, they all become Russians and remember the word "nyet." Americans don't want to raise taxes. Germans don't want to stimulate. And Japanese don't want to restructure.

And the last three or four economic summits have been incredible failures economically. Nothing has been done. They even now spend most of their time talking about terrorism or democracy or something other than economics because you can agree you don't like terrorists. You can't agree on what you're going to do economically because it would force you to confront this fact that you don't run independent economies anymore.

Now that's no big deal if you live in the Netherlands because the Netherlands has known for a long time that what goes on in Germany is more important than what goes on in the Dutch government. It's no big problem if you live in Canada because they've known for a long time that it's more import what goes on in the United States than what goes on in Ottawa. But for these three countries, who are used to being able to, in some sense, manage their own national economy and pay very little attention to the rest of the world, and certainly not adjust their policies based on what somebody else in the rest the world wants, it would be a real change in attitude and in political policy making to make that shift where you really had to coordinate with the Germans and Japanese as opposed to talk about wouldn't it be nice if we coordinated with the Germans and Japanese.

And so we sit on the economists' solutions at the moment, not doing very much about it. We have lots of conferences about it. And at the end, they always pledge great cooperation. And then if you watch him for the next six months, they never do it.

The option, the second place to go if you don't go to the economists' solution, is to for every-- and that's where we're going at the moment-- everybody retreat back to national economies. Where instead of having something you might call free trade, you have something you call managed trade. And you can see that in every country in the world.

If you look at the United States in 1980, 20% of the products coming into the United States were subject to some kind of restriction, formal or informal. Today, about 35% of the products coming into the United States are subject to some kind of restriction, formal and informal. And same thing is true in the rest of world with almost no exception.

We all look at the other guy and say protectionist. But the fact of the matter is we're all becoming more protectionist over time. The interesting thing you have to think about is if we all retreat back to-- the idea of retreating back to national economies where you control foreign trade is then you can run your own economy. You can stimulate French demand just by government fiat-- keep out the imports, force the Frenchman to buy French products, and push French production up and push French unemployment down, employment up.

Now one of the questions you have to ask yourself about that, essentially, second-best strategy, with modern technology, telecommunications, computers, et cetera, how possible is it to retreat back to the 1960s? See, the 1960s had capital controls. And if you go back to national economies, you once again got to control capital flows. With modern technology, that's certainly harder than it used to be-- maybe not impossible, but it's certainly harder than it used to be.

But I think it's reasonably clear we're not just going to sit at the end of the line. We're going to go one of those two directions. And the two directions we go obviously depends on how we choose. Do we essentially take the line of least resistance, just let the events unfold, which means we go back to national economies?

Now that has some tremendous implications politically because it probably means we will bust up our military and economic alliances. But see, it also-- the common market has got a tremendous problem because the common market is not a common market. Countries of the common market won't live up to the Treaty of Rome. Treaty of Rome says they're going to run common monetary policies and common fiscal policies. They've always been unwilling to do that. And the common market is full of these under-the-table restrictions like when Spain joined the common market, they had to agree that forever, for four months a year, they would not sell strawberries in northern Europe. I mean, the restrictions are down at that level because somewhere in northern Europe, somebody was growing strawberries under glass and didn't want to compete with the Spanish growing strawberries under sunshine.

And it's not at all obvious that the common market is going to become a common market. It's much more likely that it will split up to once again be independent countries. I spent two days last week with the prime minister of Ireland in Ireland. What would you do if you were the prime minister of Ireland? Just sit there and take a 22% unemployment rate, and then a 24% and then a 26%? At some point, you either as the prime minister of Ireland or as the Irish people say this don't work. What we're going to do when we get out may not work either, but we know this isn't working, so try something new. Don't just stand there. Do something stupid. See, I think that's human nature.

And so we're in that box. And I don't know. If you think about economic predictions, I don't know which way we're going to go. But I think that's the thing you have to think about in terms of running corporations. Because what you should do as a corporation will be very different depending on which one of those two routes we take. OK.

STAR: Thank you, Les. If I could immediately reflect what I've already learned this morning, let me revise my diagram. And it seems to me that rather than sort of saying, hey, there's some future out there, I think what we're really saying is that there's at least two, and probably a cluster. And that in planning a corporation, to some degree, we've got to determine how can we affect the future. But we've also got what kind of optimal strategies and plans would make most sense given either of those two alternatives or possibly some others.

I first about Carl Sagan back in the mid-1960s when my wife Brenda, who's actually in the back of the room, brought home a book called Intelligent Life in the Universe. As far as I know, Carl, this is your first book. It's a book coauthored with a Russian scientist, whose name I will not even attempt to pronounce.

But what to me was significant about this book, it was certainly dealing with this question, is there life elsewhere in the universe? But the real question that it asked, and it so fascinated me at the time, was not so much is there life out there, but how would we know? And for somebody like myself, who did not have a background in the scientific method and scientific inquiry, kind of puzzling through that dilemma with Carol, which is what this book really let me do, caused me again to kind of approach the world in a fundamentally different kind of way in terms of thinking about a whole bunch of things.

So for me, it's very, very exciting to have Carl with us today to help us kind puzzle out this whole question of where the world seems to be going. Carl?

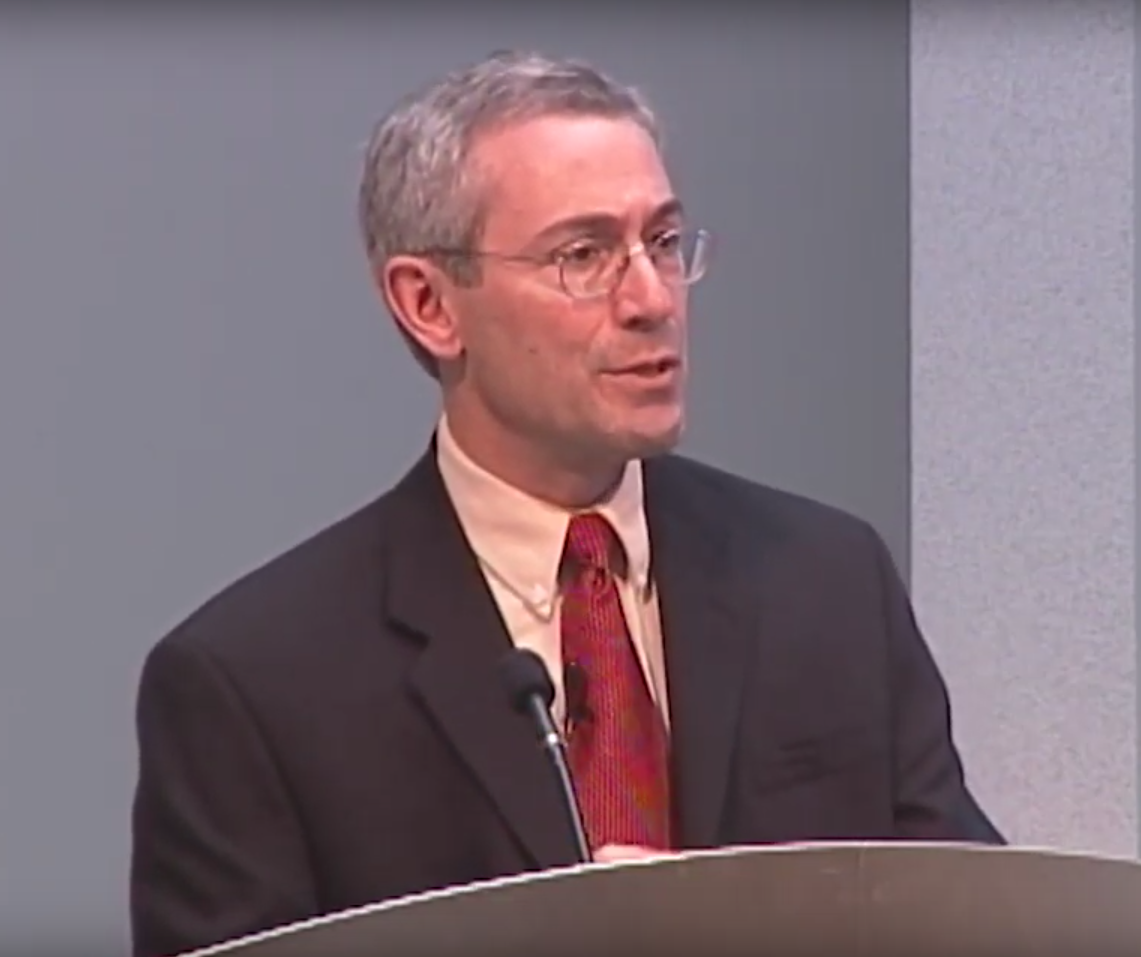

SAGAN: Thank you. I will be talking not so much about whether there is intelligent life elsewhere, but whether there is intelligent life here. I want to talk mainly about the development of science and technology and its consequences. I will make some economic statements, which, if I'm extremely lucky, will be as competent as Lester's astrophysical statements.

We are a tool-using species. It's our only hedge against disaster. Our ancestors, when they came down from the trees 10 million years ago or something like that, were not faster than the competition, not stronger than the competition, not better camouflaged, not better diggers or swimmers or flyers or runners. All we had going for us was being smarter, having hands with which we could build things. And that was and has been the secret of our success.

We were technological from the beginning. So 2 million years ago, our ancestors had a vast stone and wood technology. We knew how to chip and flake and carve. And that's how we managed to make a living. And a very good living it was. That hunter-gatherer way of life spread to all six continents, existed for a million years. And the bulk of the evidence is that most of those economies had surpluses. And that the amount of time that people work in hunter-gatherer societies, even the paltry remnants that are around today, is less than the fraction of time that people work in modern industrial economies.

So immediately there is a real question about how much progress has been made in the last million years. The technology has been monotonically developing, always for short-term advantage. It's extremely rare that a technological development is forsworn because 100 years from now we can see that there will be some serious negative consequences even though 10 years from now we can see that there will be some significant advantage. We never think on those time scales. 100 years from now, we'll be dead. Someone else's watch. Let them look out for that.

Well, this passion for the short term over the long term, coupled with extraordinary technological prowess, has, I maintain, produced an extremely dangerous and critical circumstance at the present time. The technology now permits us to affect the entire planet. And so apart from the evident economic interdependence of the planet which Lester so brilliantly discussed just a moment ago, there is an enormous technological interdependence. And I'd like to give a few examples.

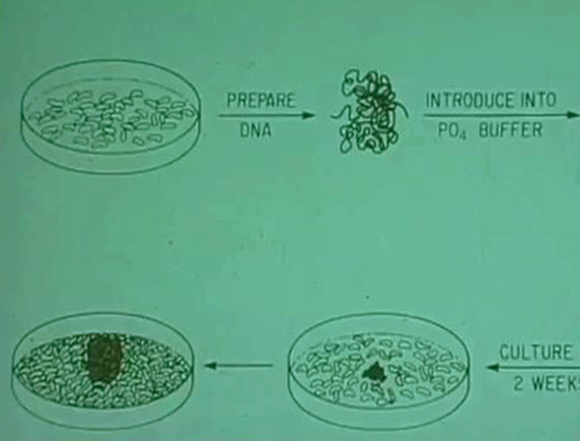

The innocent act of burning fossil fuels-- coal, peat, wood, natural gas, petroleum products-- has consequences. It seems the most natural thing in the world. The global economy is geared mainly on the fossil fuels. But every time you burn a lump of coal, let's say, you combine the carbon in it with the oxygen in the air. That's where the energy comes from. And you produce carbon dioxide, CO2.

Now let's just spend a moment on carbon dioxide. The air in this room as 0.03% carbon dioxide in it. It's a minor constituent. It's odorless. It's colorless. It's not poisonous. And it's transparent. Here we are seeing each other. It must be transparent. It's transparent in the visible part of the spectrum, the ordinary kind of light that our eyes are sensitive to.

But in the infrared part of the spectrum, the light beyond the red, it is not fully transparent. And at a wavelength of 15 microns, it's opaque. If our eyes were good at 15 microns, we could not see our finger in front of our face, which is why our eyes are not good at 15 microns because that would be perfectly useless.

Now what determines the temperature of the Earth? Visible light comes from the sun, hits the surface of the Earth. Some of it's reflected back to space. The rest of it is absorbed by the ground. That goes into heating the Earth.

And what we have is a kind of equilibrium. The Earth radiates to space just the same amount as what it absorbs from space. And that equilibrium determines the temperature of the Earth. But that is only part of the story.

The other part has to do with the greenhouse effect, so-called because of a imagined analogy to a florist's greenhouse. But the basic idea is that transparent atmosphere lets the sunlight in. But when the surface tries to radiate away into space in the infrared, that radiation is impeded by the partially opaque atmosphere in the infrared. Carbon dioxide is one of the causes. Water vapor is another. Ozone chlorofluorocarbons, there's a number of molecules that are greenhouse gases and hold the heat in.

Now the lifetime of carbon dioxide molecules in the atmosphere is measured in thousands of years. So every carbon dioxide molecule we put in the atmosphere will stay there for the foreseeable future and increases the greenhouse effect, and therefore increases the temperature of the Earth globally, the worldwide temperature. The curve of carbon dioxide is a function of time. It is a kind of increasing sawtooth like that. The up-down is a seasonal cycle of vegetation on the planet. And the amount of carbon dioxide is monotonically increasing and has been doing that for many decades, in fact, possibly since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

It is now entirely clear that the Earth's temperature is increasing as well, globally. At estimated rates of industrial and domestic use of fossil fuels, you can make some predictions. And there's, of course, some uncertainty, but a typical prediction is that at the projected rates of fossil fuel use by the middle to late 21st century, that is roughly a century from now, the global temperature will have increased sufficiently to make massive climatic change on the planet. A typical prognostication is the conversion of the Ukraine and the American Midwest into something little different from scrub deserts. That will have significant economic consequences, but on a time scale that nobody worries about because it's not our watch. It's our children and grandchildren. Let them worry about it.

Suppose that we were smart and started limiting the use of fossil fuels, made massive investments in alternative energy sources, solar power, and ultimately fusion power, thermal-nuclear reactions, what would the consequences be? Well, suppose the United States and the Soviet Union in 30 years-- not out of the question-- had economically viable fusion reactors and replaced they're entire fossil fuel economies despite enormous resistance from fossil fuel corporations? And will then everything be fine?

Everything would not be fine. The third largest coal producer on the planet is China. China is in the throes of massive industrialization. Can we imagine the United States and the Soviet Union going to China and saying, look, we know we made some mistakes in our industrialisation using fossil fuels. But please learn from our mistake. Don't you use coal as well. Otherwise, our farmers in the Ukraine and the Midwest are going to be in trouble. What's in it for China?

I think the United States and the Soviet Union would have to provide the alternative power technology at a rate which was competitive with Chinese use of coal, which will be very cheap, in order to make much of a dent in Chinese thinking. Possibly China will be much more altruistic and planet-oriented than the United States and the Soviet Union. But I wonder if we can bet on that.

Well, this is a kind of a prototype of a generic set of problems that worldwide technology now brings before us, a set of problems which involve unanticipated negative consequences of apparently benign technology, consequences very severe, consequences that are global in nature and therefore that cannot be solved even by one or two of the most powerful industrial nations by themselves. It requires the entire industrial world to deal with.

Any definition of national security, it seems to me, has to involve the well-being of the citizens' economic well-being, a positive sense of the future based not on pap but on real expectations, education especially in science and technology. The scientific illiteracy of Americans, in general, is scandalous. Every day, there are significant decisions made in Washington involving science and technology which have very long outreach into the future. And 435 members of Congress, there are perhaps two who in any sense have a scientific or technological background. The office of the president's science advisor has been downgraded in recent years. The president's scientific advisory committee was cancelled in the Nixon administration because it gave advice that was politically undesired. The laws of physics did not correspond adequately enough to the ideological wishes of the leadership. And no subsequent president thought it advisable to resuscitate the president's science advisory committee.

For a nation which is in many significant respects dependent on science and technology, to arrange things that nobody knows anything about science and technology is clearly suicidal. And some of the problems that I've been mentioning before are connected to this. How was it we didn't foresee the consequences of many of these technologies? It's because there's a very small science and technology base in the United States. There's a small science and technology base in the Soviet Union as well, but they're doing a lot more in scientific and technological education than we are.

How much science and technology do you see, for example, in the mass media? Every newspaper in America has a daily astrology column. How many have even a weekly science column? Why is this? How much science do you see on television? When somebody wins the Nobel Prize, do you ever get a coherent explanation of what he won it for? What was this discovery that was important enough to win a Nobel Price? Well, the basic sense in television is that the American people are too stupid to understand. And that it takes concentration. And therefore in the quest for a small differential advantage in the competition between the networks, that it will be a means of losing ratings to spend time explaining what science is about. Short-term advantage for the network, long-term disaster for the country.

Well, I have just one concluding remark. And that is the I know I've been slightly negative in this presentation. There is not the slightest doubt that science and technology, but in particular the scientific way of thinking, can be used in a very significant way to turn around many of these problems and to work for human betterment. But it requires a break with the idea that everything we've done in the past is OK and any criticism of it is impermissible. That so many people, for example, of both political parties, and, in fact, the United States and the Soviet Union, have invested their entire careers on the advisability of the nuclear arms race. That that already means that there is a vast vested interest in turning things around. And this is true in many of the other technological areas that I mentioned. In order to justify a lifetime of somnambulance on the critical issues, people are reluctant to even have those critical issues addressed.

So what I think is most urgently needed in all aspects of life in the United States and the Soviet Union and elsewhere is a comprehensive bologna detection kit in which the average citizen can treat with appropriate skepticism remarks made by high government officials and those justifying the continuance of the way we've always done things, whatever those things are. I think widespread critical thinking is an essential precondition for the higher standards of leadership that we desperately need and for the higher standards of education and awareness of the problems we face, which I think is required of every citizen. Thank you.

STAR: Thank you very much, Les and Carl.

[APPLAUSE]

Reflection on what we heard, it did seem to me that there were a couple things that we might want to just kind of get on board as sort of an organizing concept. Now it seems to me that on the one hand, we're talking about short-term versus long-term kind of phenomena. It seems to me that on the other hand-- OK, I'm going to hold this microphone. On the other hand, we're talking about national versus global kind of organization and management.

And obviously, this is continuous space, but if, for the sake of discussion, we were to put it in sort of a matrix, it seems to me that what both of our speakers have been saying is what we've been doing to much too great of degree is operating in a short-term time frame and from a fairly narrow national perspective.

I've never been able to draw in three dimensions, though we do have people on the Sloan faculty who can. But if I could draw in three dimensions, the third dimension I would put on the matrix would be a dimension having to do with stupid versus smart. And if you kind of view that one going out, it seems to me that our speakers are suggesting that we're sort of on the stupid end of that continuum as well.

It seems to me that a clear implication of what we were hearing this morning, in both the economics realm and in the science and technology realm, is that we damn well better move that way. Or looking at it differently, adding the stupidity-intelligence dimension, we really need to move out this way. We got to move from narrowly, national, short-term and stupid, to global, long-term, and smart.

And one of the things that we talk a lot about here at the Sloan School, of course, is probabilities. And I suppose one of things we're going to want to do before this exercise is over is a science and probabilities to that. And if we go back to this original kind of concept of essentially that we're here and the issue is where we're going, I suppose that now having heard Carl as well as Lester, I'll add a third possible environment, which wouldn't even be there, I suppose. It would be down here, off the graph completely.

All right. It's on that pleasant note that I now suggest that we kind of engage in some discourse. I would like very much by noon to have Humpty Dumpty put back together again, or at least have some sort of a plan to get Humpty Dumpty back together again.

So let me simply ask, are there any themes that we've seen this morning that anybody would like to pick up at this point?

AUDIENCE: Both Lester and Carl, in my view, basically argue, as Steve already pointed out, much the same thing. However, particularly Carl pointed out, you seem to be both arguing for a transcendence in, if you will, evolutionary and biological perspective in the way that we act and interact, the need for global cooperation, long-term planning, et cetera. In other words, Lester's technological optimism has been our historical role.

Further, you both argue, from what we have just recently learned is something we call the rational actor model, in that it's a very logical, sequential kind of thinking, however ignores all the other decision-making models that you both are talking around and about, the bureaucratic and political. On top of this, we've recently returned from Washington wherein the leadership of one of two most powerful governments on Earth freely admit that nothing happens down there without a major crisis.

How can you rationalize all of these? Because there seems to be an implicit need for multiple decision-making processes which are [INAUDIBLE] to one another, if you will, and don't seem to be occurring, even with a pending crisis.

SAGAN: There's no question that that is the problem, what you just talked about. To devote enormous fiscal, or even intellectual resources, in the government to an alleged crisis that hasn't yet broken when there are other crises that are breaking every day is considered bad politics. And the idea that a significant fraction of the resources have to be devoted to long-term problems, awkward problems, problems which fight the ideological biases in which every country is, that's a lot tougher to get going.

I tried to discuss at the end of my talk what is needed to do this. And part of what is needed is much greater public skepticism about what governments claim they're doing. I'd like just to mention as a kind of a stark perspective, you talked about a kind of evolutionary inertia. And there may well be some of that. But remember, we're a problem-solving species. That technology that's the secret of our success is all from thinking things out. We have had some spectacular changes in our world view when there were-- human species, I mean-- when there were enormous vested interests against it. And let me just mention two examples.

Divine right of kings. Now there was a time when that was the worldwide norm, that very steeply graded social hierarchies were designed by God for the human species. And at the top of each local hierarchy was a king or emperor. Think of the powerful vested interests in maintaining that kind of system. Kings and emperors certainly had a vested interest in it. They ran the agencies of national propaganda. They ran the agencies of national coercion. But we don't have divine right of kings today with one or two exceptions anywhere on the planet. I don't think Queen Elizabeth II is an advocate of divine right of kings or queens. We managed-- a course, at some cost-- but we did manage to turn that around.

Second example, consider chattel slavery. There was a time when it was considered perfectly fitting and proper that some people should own other people. You have famous philosophers like Aristotle who were widely admired talking about how some people are naturally slaves, deserve to be slaves owned by other people. And other people are naturally masters. Look how little power the slaves had. Look how much power the slaveholders had. And yet, all over the world, there isn't any more chattel slavery with some local and minor exceptions.

So we were able to make very major changes. I maintain that the vested interest in slavery by slave owners and in divine right of kings by kings is much larger than the vested interest, say, in the nuclear arms race by generals who had children and grandchildren, or the vested interest in national sovereignty to the exclusion of economic well-being by national leaders. I think you can look at our history and recognize that we have made stirring profound changes, not just in matters secular, but matters secular that were thought to be divinely ordained.

THUROW: You know, you always learn things from interesting places. About half a dozen years ago, I had a son who got fascinated by the kind of human details of the Roman Empire-- not by the great emperors, but how you build the roads, what the cities look like, those kind of things. And he was at the age where fathers read stories at night. And I remember reading an elaborate story about building the Appian Way.

And, of course, the Romans didn't believe in God in the Medieval Christian sense, but they believed in the Roman Empire, which was going to last forever. And so the Appian Way, which still exists today as a road, they first dug a trench which was literally 20 feet deep. Then in that trench, they put four or five feet of crushed gravel at the bottom, so it would have good drainage. And then they put blocks of granite what were 10-foot squares. And if you think about what technology they had in those days to drop 10-foot blocks of granite into this hole. And then you overlaid it with paving stones that were two feet thick. And ask yourself when is a road like that going to wear out?

The answer is they're still driving on it in Rome today. But they weren't doing it because somebody 2,000 years ago said, hey, I got to build a road for the Romans in 1987. They were building it because they didn't have this-- they had a very different conception about how long things were going to last. And I think maybe, in some sense, we know-- in that sense, we know too much history. Because we believe, partly because of the Industrial Revolution, everything is going to change so radically that anything we do today is waste tomorrow. It won't be used. It will be obsolete. And so no modern road is built to the specifications of the Appian Way. Modern asphalt roads, if nobody drove on them, would disappear within 15 years because the bacteria eat them, eat up the asphalt.

SAGAN: This is self-confirming prophecy.

THUROW: What's that?

SAGAN: The idea that we shouldn't build for the distant future because things will decay before then. If that's your view, then, of course, things will decay before then. But can I just say, you don't have to build for God. You just have to build for your children and your grandchildren.

THUROW: But it's harder to build for your children. You don't like them as well as you like God.

AUDIENCE: I'd like to come back to your options for the near future [INAUDIBLE] was your first option, that need for the cooperation of the United States, Germany, Japan, or others. And one of the major topics we are talking in Japan now is restructuring. This is a sample of the books in Japanese. But this says restructuring, as you can see in English here.

This is a major topic. And without doubt, our government is going ahead for this direction. And one of the problems we are facing is a cultural changing involving with this restructuring. Our culture, ethics, originally saving is a virtue. Spending is a vice. And so import is [INAUDIBLE] luxury. So spending on a luxury item is a vice. So we have to restructure our culture totally. That is no problem. Our next generation, they are spending money. And everything they wear is import from top to bottom. So no problem. That can be achieved in next generation. But we cannot wait until the next generation. We have to do something in my generation. That's what I feel.

And the reason for what we are doing is moving our production site to offshore and recently more to the United States. We used to move more to Asia and Europe before now recently moving more to the United States, both assembly and components plants. And I'm wondering, in addition to that restructuring, does it help your economy, or United States' economy, for long term, is it good or bad? And how does it effect if we move our production site, both assembly and components, to worldwide? How does it [INAUDIBLE] to the United States and worldwide economy?

THUROW: If you think about what you were talking about vis-a-vis Japan, the real question here is which way do you think we're going to go? If we take the route towards a general global economy, then very quickly every country will be in some sense a transnational country, a transnational company where you'll be doing various things abroad. And certainly one of the things you would expect is if Japanese are good at making cars, and currency values change, then we don't quit buying Japanese cars, but we do start buying Japanese cars made in America as opposed to Japanese cars made in Japan. And that helps solve out these trading problems.

But, see, I think that the thing to remember is we're all history. And we're all good at certain things and bad at certain things. For example, Japan is super when it comes to exporting. Japan, so far, has proved to be lousy when it comes to managing offshore production facilities. It's just a very different-- see, Americans are lousy at exporting, but American companies sell 25% of the cars in Europe. They sell a substantial fraction of the cars in Japan. But they do it by foreign ownership as opposed to exporting from one country to another.

And [INAUDIBLE] Securities, for example, in New York City has had tremendous problems mixing Japanese and American workers. Because the systems are so different, it's very hard to do it. And so if you think about how you have to change your corporate culture, I think it depends a lot on-- if we're going to go back to kind of more nationalistic economies, then you can think of let's run a Japanese corporation the way we've always run a Japanese corporation. We have to change some things at the margin, but we don't have to change the central culture. If you think we're going to this global economy, then in some sense the whole concept of a Japanese corporation kind of disappears. It's not that you have to become an American corporation, but we invent something which is different, where I, an American employee, might have a chance of getting to the top of what used to be a Japanese corporation. You, a Japanese, might have a chance of getting to the top of something that used to be called an American corporation.

Now I think these kind of historical cultural blinders are very strong. I was in Japan in July and asked to meet with the MITI group at the Ministry of International Trade and Industry for a couple of days about their various problems. And, of course, one of the problems is housing. And I made this comment about you've got fewer people per square kilometer than the Netherlands. But they said, but we've got all these mountains. We don't really have as many square kilometers as it looks like if you just look at it on a map.

And, of course, that led to a discussion about something that's always fascinated me in Japan. Nobody ever builds a city on a mountainside. And if you go to Italy, every city is built on a mountainside. And so I started asking these people at MITI, why don't you ever build houses on these hillsides? And they said, well, they would occasionally slip down the hill. And, of course, that's true in Italy. Occasionally, a village does come down a hillside. But most of the time, a village doesn't come down the hillside.

AUDIENCE: What skills developed to emphasize in terms of our undeveloped as we go on to the year 2000 in any of the scenarios [INAUDIBLE]?

SAGAN: I would say extreme skepticism about ideologically-based pronouncements on either side. A kind of thinking which I think is best encapsulated in the scientific method. Arguments from authority have no weight whatever. Experimental investigation is desired. Vigorous debate is encouraged. The recognition that people from a variety of backgrounds and countries have important contributions to the problem. And the general increase in the sense of globalism, the awareness that we are all in the same boat together and we have to solve our problems jointly.

A great many of our problems have to do with a residuum back from days of jingoistic nationalism, which is not only counterproductive, but extremely dangerous today. There's a kind of reworking of things in the human heart that is essential. And I agree with what Lester said before about technological fixes. Many of these problems are not fundamentally technological. They're fundamentally political or psychological or psychopathological, and have to be addressed on those grounds.

AUDIENCE: One of the ways that people restructure their thinking is through having role models, people to identify with. And I'm dying to ask you both whether you see any role models among the politicians and leaders of the country today, since we're about to face an election.

STAR: But putting this into context, it seems to me what we're fundamentally grappling with here is the question-- it seems to me we've laid out a precondition that says, essentially that the world, or at least the other world broadly construed, really needs to go through some pretty fundamental changes over the next decade or two. In the absence of that, the long-term consequences-- I think what we're hearing-- from both the economic and the science technology perspectives are very, very serious. It seems to me this discussion of politics, of governments, of stakeholders, of the media, of public opinion-- it seems to me this is all very highly germane because what we're really talking about is the impediments to the kind of change that's required.

Now Carl earlier cited both the diminishment of the divine right of royalty and the end of chattel slavery as fundamental shifts within memory that have taken place. Both of those, yes, I believe, however, were-- at least the conditions for them included significant economic change and at least a certain amount of military conflict. The question, I suppose, we really have to raise, and I guess this is a suitable point to ask, is, given these impediments, it's relatively-- certainly not easy, but we can sit here in the here and now, and we can say this is why things go wrong, and this is why things go wrong. Yet we claim to be, if not optimistic, not a pessimist. And so, I guess, the real question is, how do we expect to get over these things? Presumably we're not critiquing democratic processes when we talk about public opinion. We are not advocating warfare. How are we going to do it?

THUROW: But see, I think it's exactly the same problem inside a firm. You don't elect a leader of a firm by democracy, exactly. But you do, in fact, select leaders of firms. And the question is, does this selection process turn up the right things?

And see, I am always amazed how the similarity-- let me make a similarity between the Soviet Union and General Motors. I would argue they have exactly the same problem. The problem in the Soviet is very simple. In some sense, the economy has worked very well over 70 years. They've gone from being an underdeveloped country to a superpower. The GNP is growing just about as fast as the United States. They're not sinking relative to the United States. Why, then, does Gorbachev want to turn the world upside down and to have a change in the structure? And who's the opposition to changing the structure?

Well, Gorbachev's reading is the world has changed. And they won't succeed in the future doing exactly what they've done in the past. And they've got to change the institutional structure to do that.

And my reading of the Russian mind when I was there is they don't worry about the United States being wealthy. Americans were born wealthy. And in some sense, don't worry about the Germans being wealthy. The Germans have always been wealthier than the Russians.

What they can't explain to themselves is Korea and countries like Korea because they have always looked down on these people as being backward, poor, et cetera. And now it's to the point where it looks like the Koreans will pass them, and countries like that. They're having to do some very fundamental internal examination. Maybe our system doesn't work as well as we think our system does.

And If you look at General Motors, they lost no money in the 1930s, never lost money in the Great Depression. In the 1960s, s when companies like Volkswagen were taking 10% of the American car market, they took almost none away from General Motors. In the 1970s when the Japanese were taking 20% of the car market, they took the 10% European share and 10% away from American companies, but almost none of it was from General Motors. And General Motors had 50 years of success. And then you come to a time when the world changes in the 1980s, and it don't look so successful. And then the question is, how do you change?

Now the opposition in the Soviet Union is very clear. My most interesting experience in the Soviet Union was a failure because I've been there are a number of times. And when I got there, they said, would you like to see some of our factories? And I said, well, no. You've shown me a lot of obsolete consumer good factories over the years. And if you want to show me another lousy television factory, I don't really want to go. I was a little politer than that, but not much.

And so they finally said I was being hosted by Yakovlev, who was the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party who used to head the Institute for World Economics. And so they finally said, and this an instance of glasnost, they said, we're going to send you to the leading machine tool manufacturer in the Soviet Union. This is a plant where no Westerner has been in it since 1945. And presumably they make military equipment among other things if it's the best in the Soviet Union.

So a fellow who was the deputy director of the Institute for the Study of the USA-- which would be like being an assistant secretary of state in the United States-- he and I get on a train in Moscow to go to Leningrad where this plant is. We get to the plant gate, and the manager of the plant looks at me. And he doesn't say this, but you can see what he's thinking. There is no way I'm going let this bastard in this plant. He might have permission from Gorbachev, but I don't know who's going to be running this society a year from now. And I don't want to be accused of letting a spy in this plant. And I ain't going to do it.

So today is not convenient. Tomorrow, I've got to check with Moscow. And he knows he can out-wait me. Four days later, the two of us are still cooling our heels in Leningrad, and we never do get in that plant because Gorbachev has got this tremendous resistance from the level of plant managers for good reasons. They're the winners. They may even believe that the new ball game will be more productive than the old ball game. But why would you want to play a new ball game if you're winning the old ball game?

And see, the same thing is true in General Motors. People there tell me that the real resistant to changing the way they're doing things is at the level of plant managers. They're having tremendous problems, I'm told, out at the NUMMI plant in California where they're trying to rotate General Motors managers through that facility supposedly learning Toyota techniques because General Motors managers at the plant level exist to give orders. They're not into participatory management. That's never been the General Motors style. And you might even have picked human beings that are more into the order-giving view of the world than the participatory view of the world. And how do you change them?

And see, I would argue to you that General Motors has almost exactly the same problem Gorbachev has. The hardest time to change is when you have 70 years of success. And then you got to tell the people in the bowels of the organization, it don't work anymore and you've got to do something different. And the plant managers in Russia-- and I would suspect the plant manager at General Motors-- have exactly the same answer. Get the bureaucrats out of Moscow. Get the bureaucrats out of headquarters in Detroit. And we'll make the damn thing work. We'll make it work in the EVA strategy-- we try harder. If we gave 1,000 orders last year, we'll give you 1,500 orders this year. And we'll simply try harder doing the old ways.

And I think that's an institutional problem that exists at all levels. And it's a problem that's most acute when you've been successful. And, of course, the United States has been very successful. And that's one of the reasons why we find it very hard to change.

The thing that made it easy to change in Germany and Japan after World War II is they had just been spectacularly unsuccessful. If they had won World War II, they would not have changed.

STAR: Carl?

SAGAN: I'd like to have time for some more questions.

STAR: Sam?

AUDIENCE: I'd like to raise a question about automation, which, in a way, is related to what you just said. There is increasing automation in manufacturing industry, certainly in the United States and other developed countries. Automation leads to loss of jobs, fewer jobs than before. The argument has been made that these people move into the services industry.

Now my question is, is the service industry capable of absorbing all these people as well as people who would otherwise have gone into manufacturing industry in the future who are now no longer going to be going into the manufacturing industry because the absorptive capacity of manufacturing industry is doing down? If the answer is no, if the service industry cannot absorb all of these people, what is going to happen to them in the future, in the year 2000? See also, if the answer is no, how are we going to be distributing wealth in the future? And how is this going to impact on the self-image, self-worth of these people who are going around without jobs?

THUROW: I don't think it's an employment problem. The question is, do we organize ourselves in such a way that we do, in fact, employ our workforce and we train them to the right level in terms of education and training? See the problem Carl was mentioning about the American school system is we're turning out 25% at the bottom. Where if you look at what-- it isn't that you couldn't employ them in the year 2020. It's that they will be unemployable in the year 2020 because they won't have the capacity to absorb what you have to absorb to do that. And so I don't think it's an employment problem in that kind of square peg, round hole sense. It really is a social organization problem.

STAR: OK, well, we're running out of time. In fact, we've run out of time. At lunch, what we're going to do is really try to deal with the question, what are the implications of this for senior management? And I would suggest that in a general way at our lunch, we really pick up that question from two dimensions. One, it seems to me that the phrase "senior managers" implies leaders. And there's no reason why we necessarily have to assume that future scenarios are totally out of our control or that we can't have impact on them. I think if we're really serious about being senior and really serious about being leaders, there has to be the question raised, what can we and, perhaps more importantly, what can our firms or our organizations under our leadership do to exert leverage that, in fact, can impact where the world is going? I think that's an important realm for us to consider.