F. Modigliani, P. Samuelson & R. Solow, "The US Economy: The Last 50 Years and the Next 50 Years” - Ford/MIT Nobel Laureate Lecture Series

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[APPLAUSE]

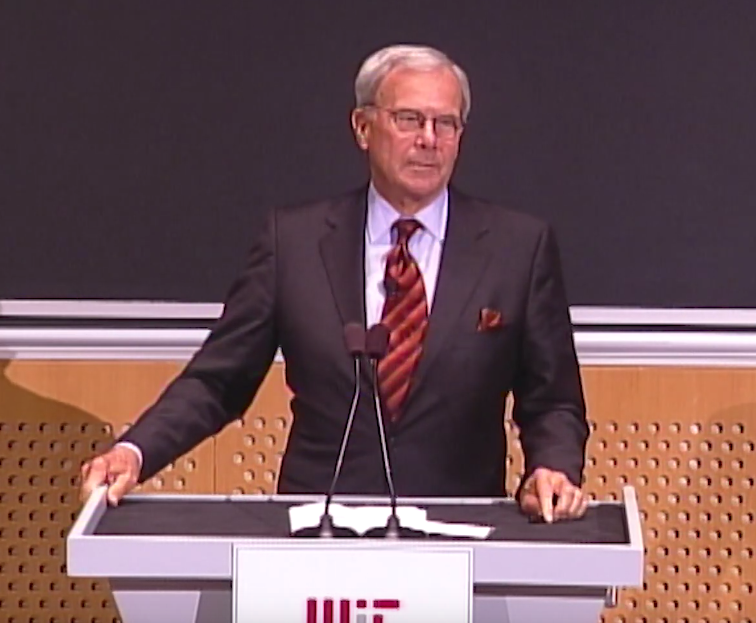

BACOW: Good evening. My name is Larry Bacow, and as Chancellor of the Institute, it's my pleasure to welcome you all to the inaugural lecture in the Ford Nobel Laureate Lecture Series. This series will bring Nobel laureates to MIT from throughout the world to discuss important work in their fields. All of the fields in which Nobel Prizes are awarded will be represented in this series. Ford Nobel lectures will be scheduled throughout the fall and the spring terms over the next five years.

We're very grateful to Ford Motor Company for sponsoring this series. It's part of an extensive partnership between Ford and MIT which focuses on research and education. MIT faculty and students are working collaboratively with Ford in a variety of fields that encompass virtually all five of MIT schools. We're collaborating on projects as diverse as the environment, e-commerce, combustion engineering, virtual engineering, and virtual education. This partnership is helping to define new models of university industry collaboration and we're very proud of it.

It had been my plan at this point in the evening to introduce Dr. Martin Zimmerman, the vice president for government affairs at Ford who was going to introduce our speakers. Unfortunately, Marty's plane has been delayed. And he'll be joining us later on in the program. So it becomes my pleasure to introduce our three speakers. I've invited Marty when he gets here to come up and actually close the program and thank our panelists.

Since I won't have an opportunity to properly introduce him at the time, just let me tell you a little bit about Marty. He's an alumnus of our economics department where he received his PhD, former faculty member and our Sloan School, after which he went on to become a faculty member at the Graduate School of Business at the University of Michigan. He's been a wonderful friend of the Institute and has played a major role in helping to create the Ford MIT partnership. And we're very grateful for his help and in sponsoring this event today.

Our three speakers tonight really need no introduction. Now Marty told me when I spoke to him earlier today that he once said that when he was about to introduce one of his bosses. And the response was, well, you know, that's true, but I prefer if you go ahead and did it anyway.

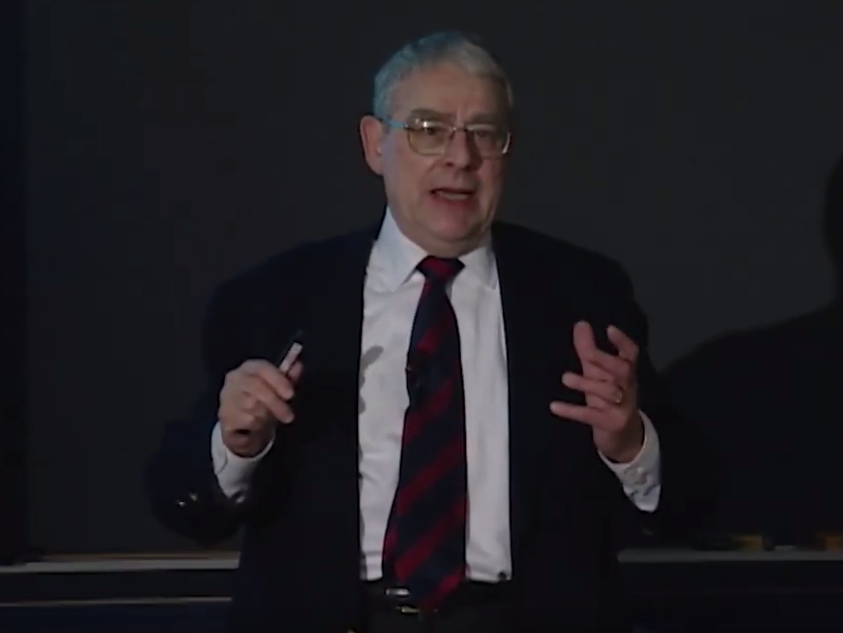

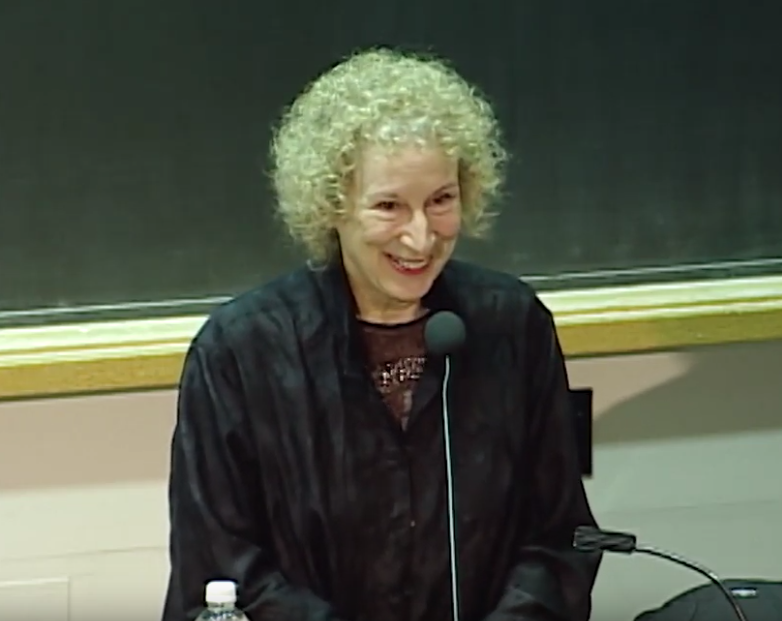

So let me just say a few words about Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani, and Bob Solow. If I really tried to describe all of their honors and awards and honorary degrees, we really wouldn't have time for the interesting work of this evening, which is their remarks. So I will be brief.

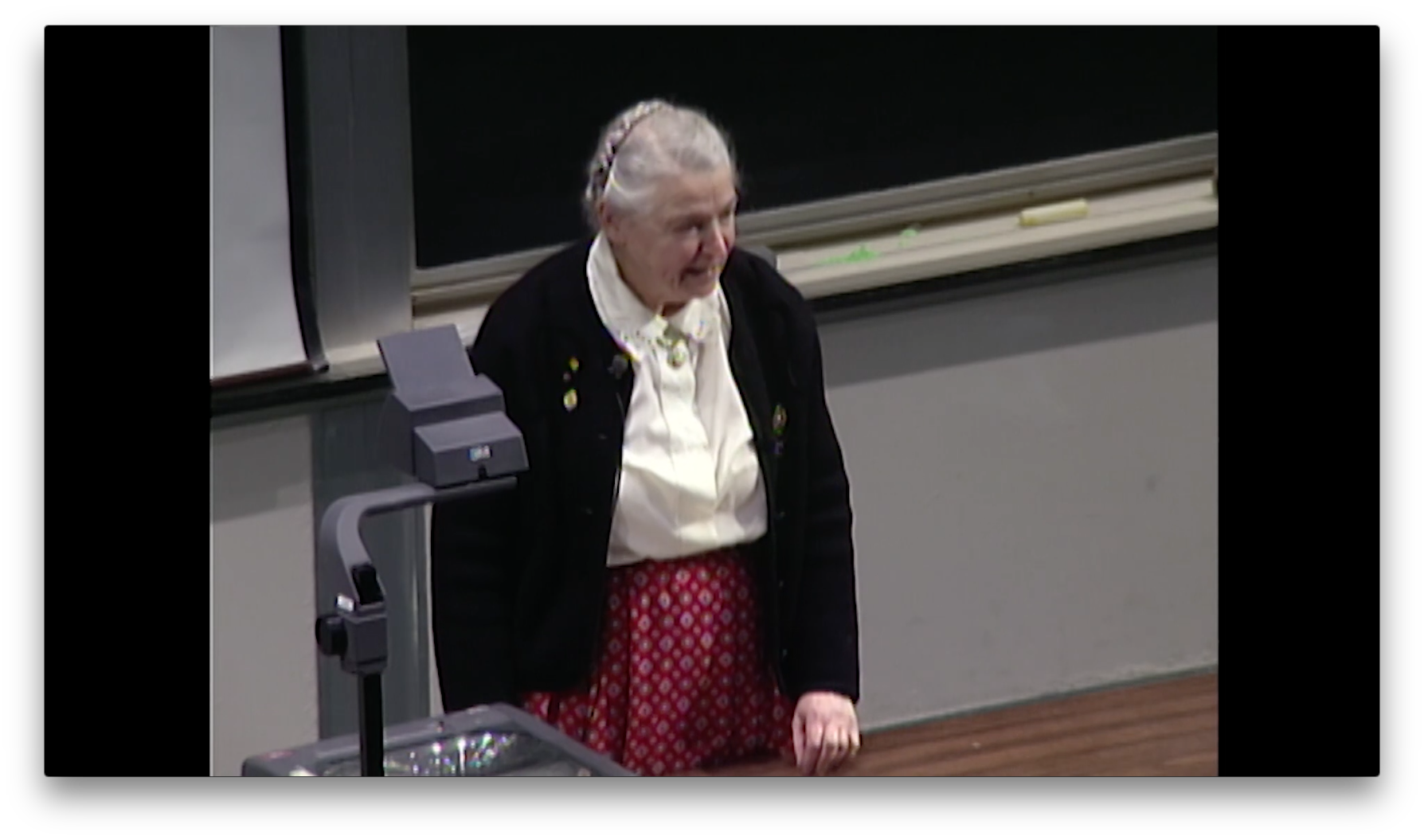

Professor Samuelson received the Nobel Memorial Prize in economic science in 1970 for the scientific work through which he has developed static and dynamic economic theory and actively contributed to raising the level of analyses in economic science. That's a direct quotation from the Nobel citation.

As Assar Lindbeck said in the presentation speech, Professor Samuelson has, in fact, simply rewritten considerable parts of economic theory. He has also shown the fundamental unity of both the problems and analytical techniques in economics. Any introduction of Professor Samuelson would not be complete without noting that he is the author of what I believe is the most popular textbook in the history of not just economics but all of American higher education.

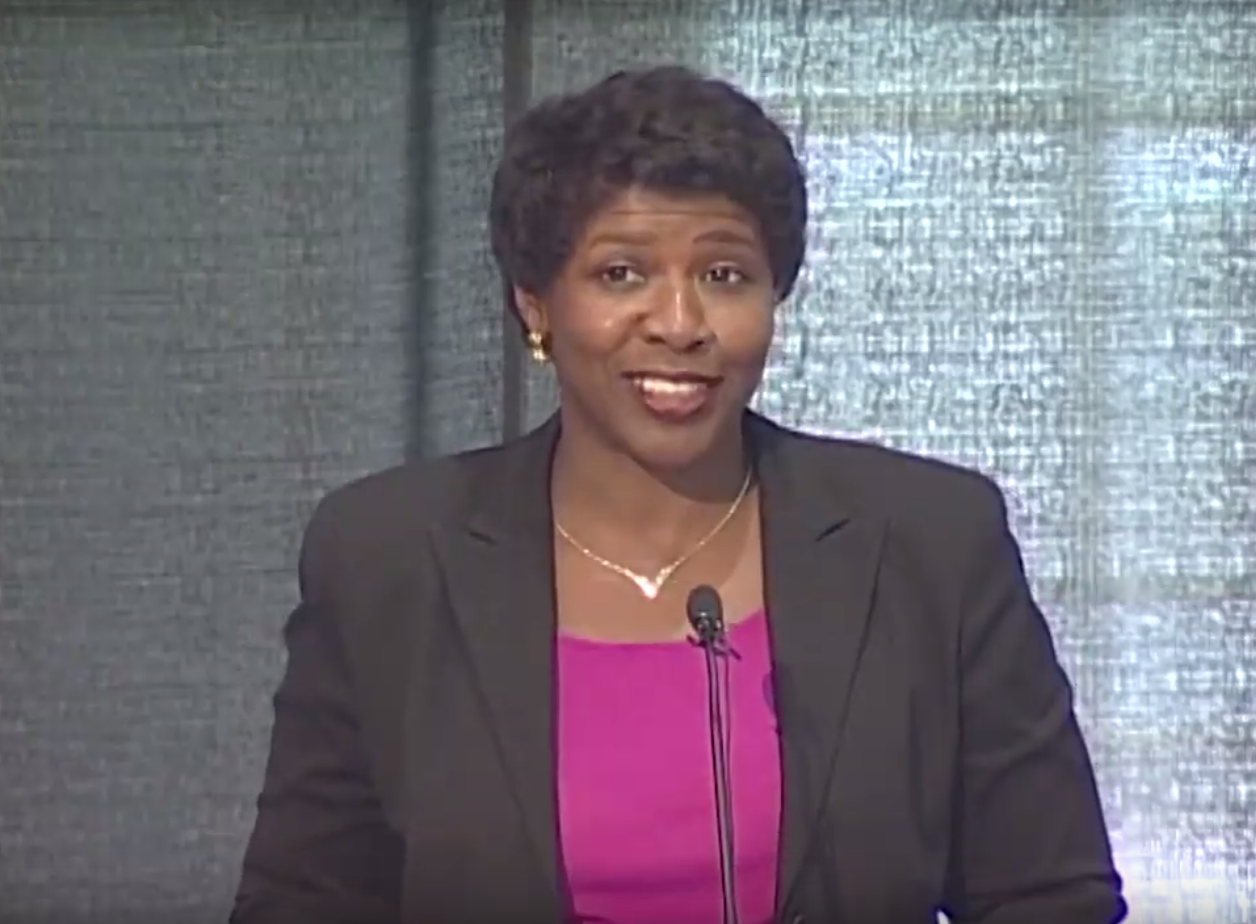

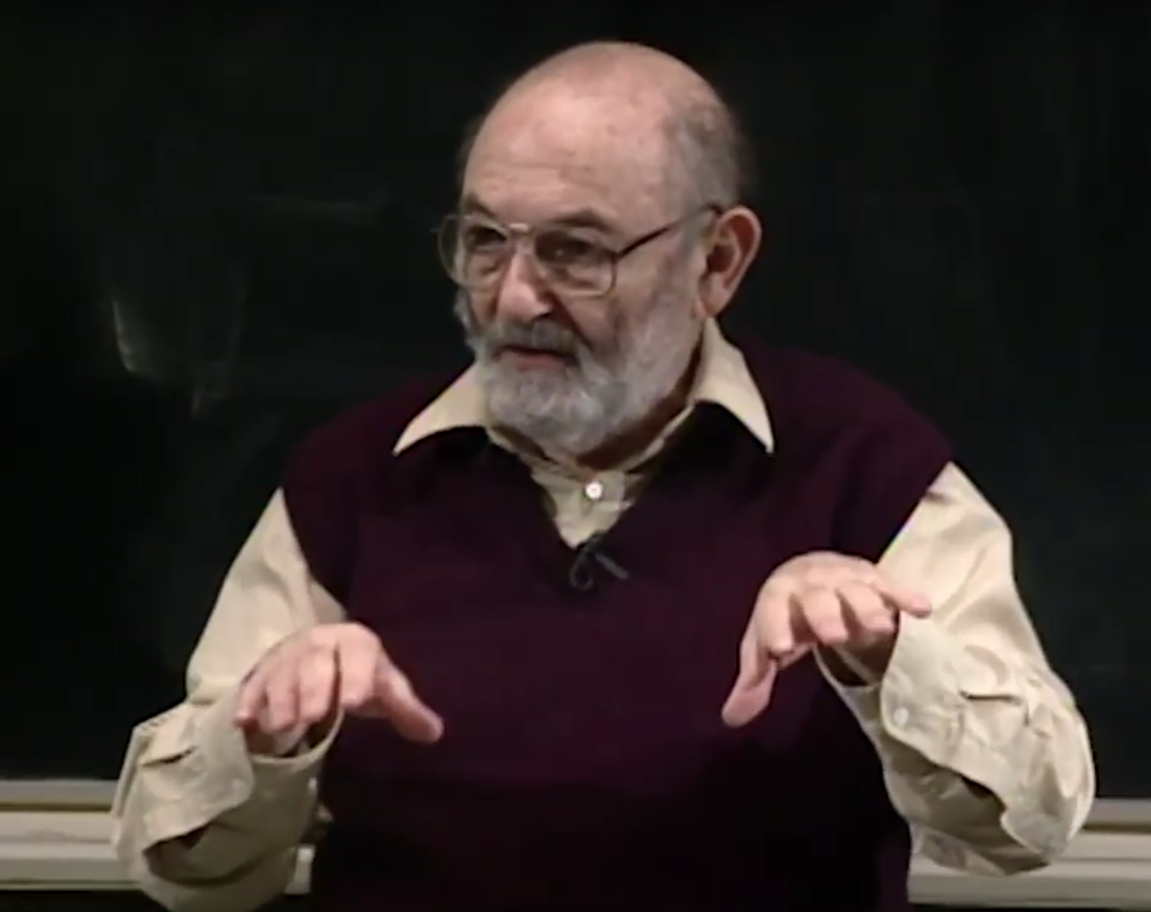

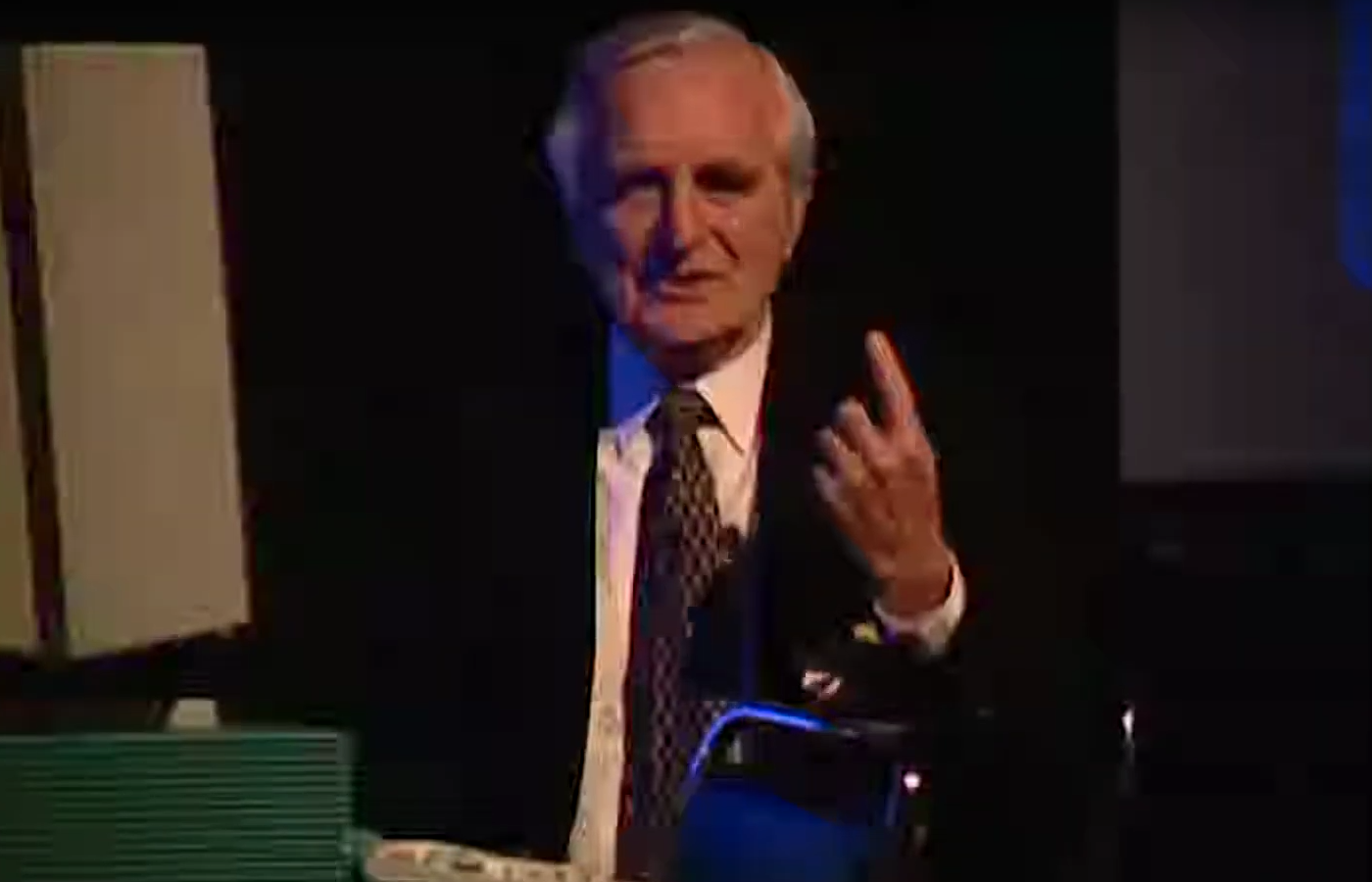

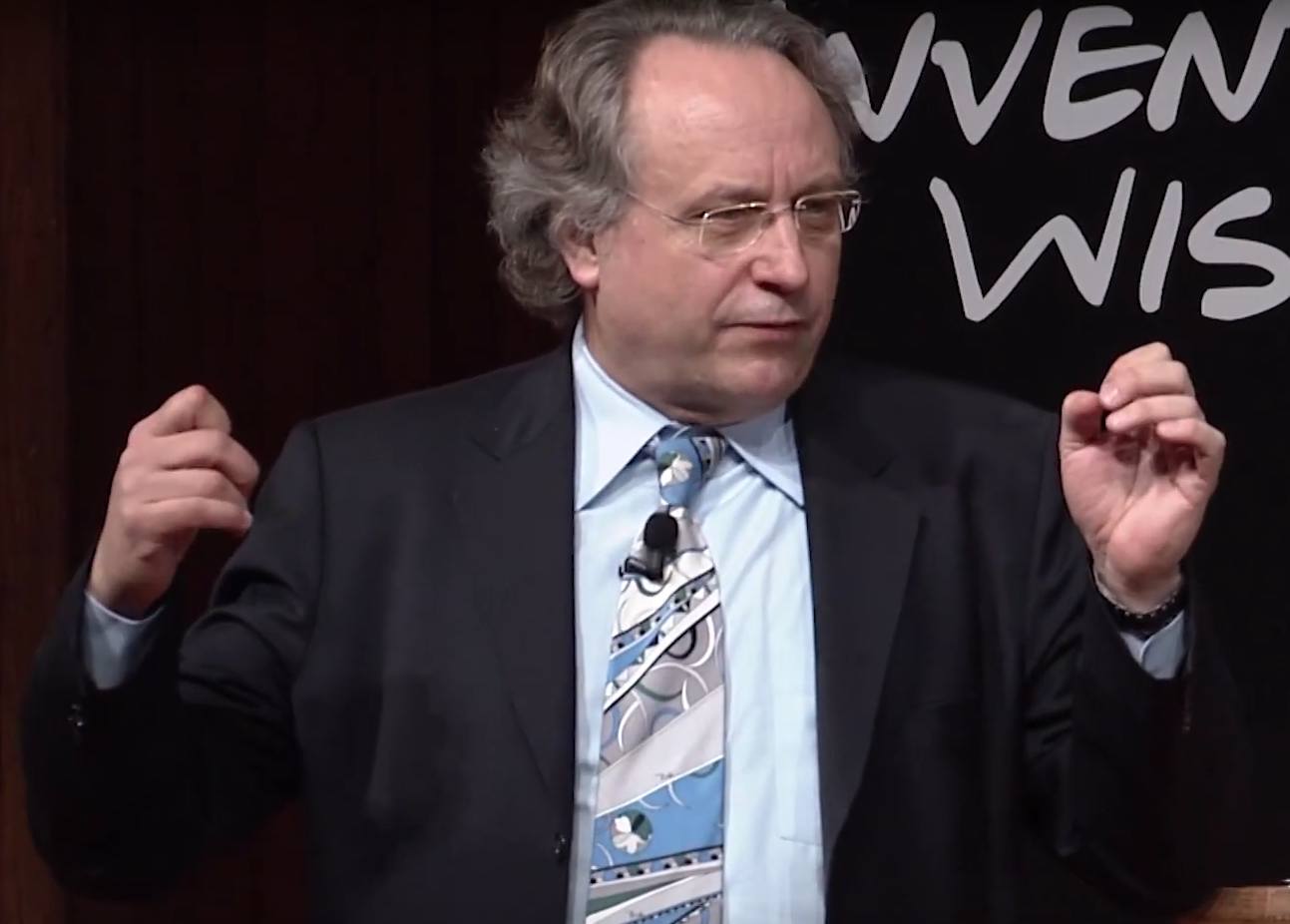

Professor Modigliani received the Nobel Memorial Prize in economic science in 1985 for quote, "his pioneering analyses of savings and of financial markets." The achievements for which he was recognized included the life-cycle hypothesis of household savings and for the formulation of the Modigliani-Miller theorems of the valuation of firms and of capital costs.

Franco has been a consultant and involved with governments throughout the world. And we have all been very grateful for his contributions to our economics department as with Paul for many, many years.

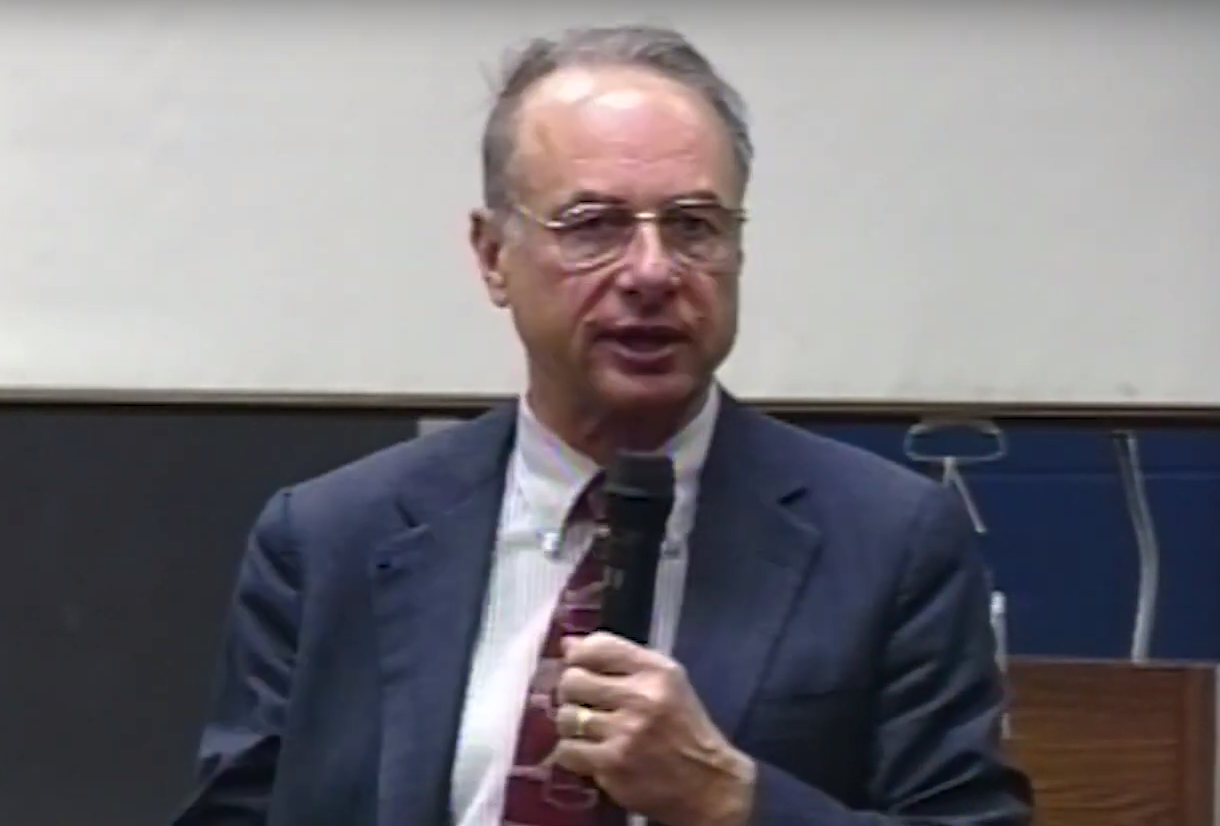

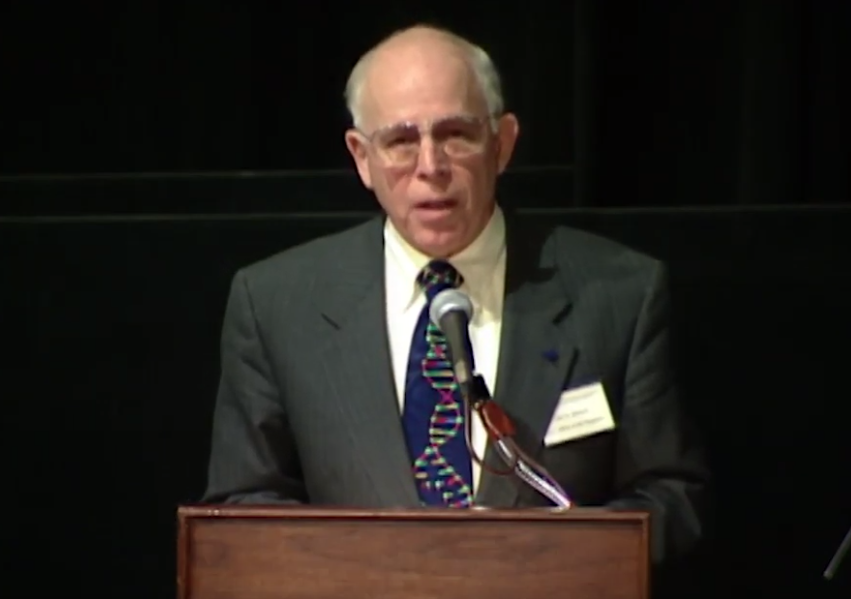

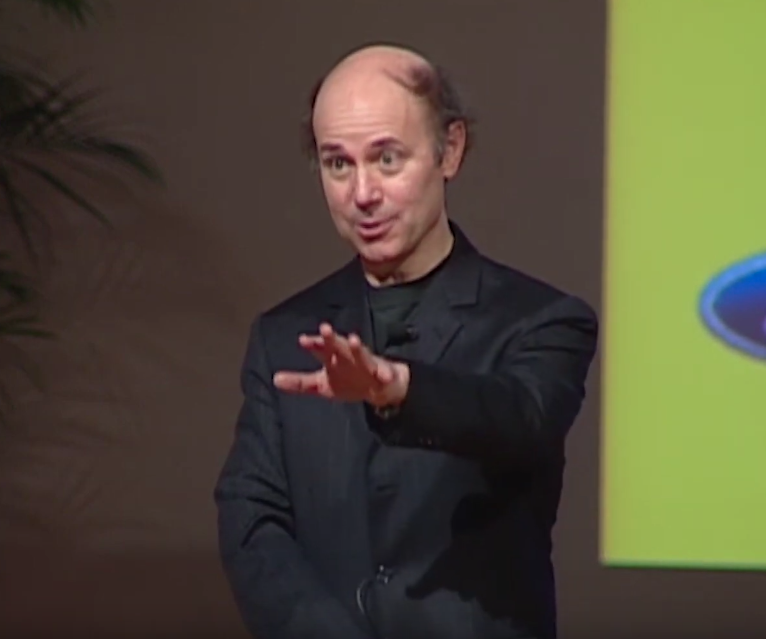

Professor Solow received the Nobel Memorial Prize in economic science in 1987 for his contributions to the theory of economic growth. The Nobel Committee cited the enormous influence of the Solow growth model and his work on empirical growth analysis. And, indeed, as we come to understand the role of technological change and productivity and the role that it is playing in our economy today, again, we turn to the work of Bob Solow.

Now, the Nobel Prize recognizes the contributions of these three men to the field of economic science. It really is awarded for their research. But in point of fact, beyond their research, each of these men have made absolutely enormous contributions to the education of generations of economists, not just at MIT, but throughout the world. Indeed, I don't think I'm overstating it when I say that they are at least as loved and as is well-regarded for the wonderful work they have done as members of our economics faculty as they are for their contributions to economic science.

So tonight, they are going to take the long view, both back and forward, taking a look at our economy the last 50 years-- and what I'm sure everybody's anxious to hear-- their prognostication of the economy for the next 50 years. Please join me again in welcoming three giants of our field, Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani, and Bob Solow.

[APPLAUSE]

SAMUELSON: The last time I saw this hall full to overflowing was when I had the duty to debate Milton Friedman. It was a question of one lion and one Christian. And I will not tell you which part was mine.

Tonight, I expect, will be a piece of cake. All I have to do is to discuss with you the major economic problems in the upcoming decade. When I first wrote my best selling economics textbook at World War II's end, I correctly identified what would be the major economic problem of the upcoming quarter of a century.

Simply put, it was avoiding the depression, unemployment that blighted the 1930s. That was then. Now is 2000. My choice now, looking ahead, not to a quarter of a century but just for a decade, is what is the major problem?

And I believe it to be how to work out the Aristotelian golden mean that weighs the delicate compromise between what we render to the market price mechanism and what we render to democratic government interferences by the democratic welfare state. And my remarks build up to that problem.

Back at the end of World War II, all the standard textbooks were still stuck in the 1920s orthodoxy of pure capitalism. I knew that system. I grew up under that system.

I sold Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Posts. There were no unions. Up to the time of my infancy, childhood, and adolescence, that was the system. But after the Herbert Hoover slump-- that is the only partisan remark I will make in the evening-- MIT students and college beginners everywhere needed to learn the Keynesian macroeconomics that ushered in a generation of unprecedented global growth in the third quarter of the 20th century.

For better or worse, Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal moved us into a mixed economy-- not pure capitalism, certainly not bureaucratic command communism of the Stalin and Mao type. Here at home and similarly abroad almost everywhere, the quasi welfare state evolved.

Now what does that mean concretely? It means most of the business of the society, the economic business is left to the allocation of market price mechanism-- profit, loss, selfishness, checks and balances. First this was, so to speak, a Monday to Friday affair. But then on Sunday and, increasingly, even on Saturday, democratic governmental legislatures and agencies did lean against the wind of the glaring inequalities generated by the competitive price private property mechanism.

Well, how did they lean against the wind? It wasn't old fashioned socialism, government ownership of the means of production. It was done, as far as the redistribution of income, to attenuate the worst inequalities, which will always be generated by a laissez-faire private profit system. That has to be done by the fiscal system.

Progressive taxation takes more from the rich than from the poor. Redistributive transfer expenditures, unemployment insurance, social security, poverty, and welfare programs, bank deposit insurance, give to the poor and lower income classes more than it takes from them by taxes. Well, I won't use time to describe that process because you've all lived in that.

You were born into it. You've grown up into it. However, about in the third quarter of the century, towards the last part of the century, nature cannot stand relative prosperity and stability and complacency.

By the quarter of the century just ended, in much of the world there has grown up a conservative trend away from altruism. That is a fact about modern democracy, a different fact from the laissez-faire society-- I'm sorry from the 1929 drift away from the laissez-faire society.

And you've seen it all over the globe. You've seen it in presidencies of Eisenhower, Nixon, Reagan, elder George Bush. Even in Scandinavia and continental Europe social democracies retreated under attack.

Now, let me give you my take on the two reasons for this. It's axiomatic that always the affluent will hope to use their money power to resist populist demands to have the government help the masses at their expense. I'm speaking of my suburban neighbors, people you all know, mostly, actually, your own parents, yeah.

However, before Keynes showed us how to mostly tame depressions the lower 3/4 of the income classes of the electorate suffered enough to goad them into opposing the disproportionate powers in democratic real politic of private business and of affluence. Our system is one nose, one vote. But our system of how the votes count is that if you have lots of dollars in your wallet, your effective voting power will be greater.

So in the age after Keynes, discontent atrophied and lobbyists learned how to operate. Also many, from even the lowest part of the middle classes, came to overvalue their own lottery ticket probability of being one of the rich favored by politics. If you're taking notes, I hope you'll rewrite those tongue-tied last couple of sentences.

But there was a second possible reason for the retreat from voter-imposed altruism. We do-gooders are like Oliver Twist. We always ask for more. We are like the boy who said he could spell banana except that he didn't know when to stop.

Going all the way, as Lenin, Stalin, and Mao did, was motivated, said it was motivated by good, if unrealistic intentions. But I'm not speaking of communism and the recent ending of the Cold War. I'm speaking of societies like those in Scandinavia, in Israel, all over the world. Once modern democracies began to spend and organize more than 50% of society's potential GDP two things seem to begin to happen. Now, I'm giving you my slant, my reading of events.

High tax rates do begin to put considerable sand in the economic cogwheels. The mathematical economist discovers that these deadweight losses against the efficiency and growth progress will increase with the square of the altruistic scale. I'm talking MIT talk.

I do not deny that any noble cause should be pushed some distance into the law of diminishing returns. But remember, we have only one human nature. It's that which evolved from the Darwinian struggle for existence. And it seems to have left us, all of us, with only a limited endowment of this precious altruism. So altruism, I believe, does need to be rationed carefully precisely because of its scarcity.

Well, that's not all about big government. I started out as a-- how shall I describe myself. I was trained by Jesuits at the University of Chicago. The cathedral of choice at my University of Chicago was the cathedral of free private enterprise, not of the medieval Catholic church. But once I threw off that brainwashing-- because I was like a sponge, I was a very good student, so I was a sponge-- I reached a balanced value judgment position.

Now, has it changed? My arteries have hardened. Have I followed the usual course of becoming more conservative as I age? Now, I'm the greatest expert on me. So I would just tell you that I don't detect in myself very much of a great change in value judgments.

However I haven't been asleep all these years. And it was a great event for me when Joseph McCarthy undertook a witch hunt in the United States which reached deep into every governmental circle, deep into every academic group. And I suddenly realized what one big employer means. When innocent friends of mine were blackballed and lost their job, if we'd gone all the way, if we really were a one employing company, there would be no place to hide.

They went to work for hardware stores. One became a treasure of Mars candy company. There is a certain protection for all of the do-gooder liberal things that I treasure in not having one big company.

Moreover-- and this is an economic finding that I cannot document precisely-- but something seems to happen when even in a very civilized part of the world like Scandinavia that part of the GDP that goes through government hands becomes 50%, 60%, when tax rates become 92% out of every dollar, you don't teach much night school or summer school under those conditions. It isn't just that sand in the cogs that I spoke of earlier.

But there is something that becomes unresponsive to human needs in the decision making of the lobbyist, politician, world that leads me to the conclusion that whereas I used to in my MIT class speak of the mixed economy, of the welfare state, I now speak of the limited mixed economy, the limited welfare state.

And so that brings me up to the topic that I started out with. What is the best compromise, what are the best limits so that we get the advantages of the regulatory powers of democratic government, of the stabilization powers of a Federal Reserve central bank, of a fiscal policy, which leans against the wind when there are no jobs it's the right thing to lower taxes, it's the right thing to run deficits, but it is not the right thing to do those same things when we are in a overheated, very high employment economy?

Now, there are no simple rules. Young assistant professors will spend their lifetime in working out documented progress on that problem. And that, I think, is the major problem. And maybe some of it will come out in the discussion that follows. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

SOLOW: When we drew lots not so long ago, the decision was that Paul would speak first on this panel and I second and Franco Modigliani last. So it's my turn now. And I'm going to talk about slightly different things from what you've just heard from Paul Samuelson.

The first thing you should keep in mind-- remember what the title for this symposium was, the last 50 years and the next 50 years-- you should keep in mind that the years from 1950 to 2000 were, in most economic ways, in this country extraordinarily successful. By the way, the period from 1950 to 2000 fits my lifetime very well.

1950 was the year in which I finished my PhD thesis and began teaching at MIT. So the next 50 years will cover roughly the corresponding period in many of your lives. The next 50 years are the years between-- the graduate students in the room-- between now and when you are old and doddering like us.

The question that was raised, that we want to raise and I want to raise and discuss here is you should be thinking about is whether the next, whether you will have it so good, whether the next 50 years can be as successful as the last. I don't want to bore you with measurements of how much better or how well the country did in the last 50 years. But one simple statistic is that real consumption spending per person in the population, what the average expenditure on consumer goods and services corrected for inflation was, in 2000, 3 and 1/2 times what it was in 1950.

Measured that way, the standard of living multiplied itself by 3 and 1/2. By the way, I was a little shocked to discover that in 1950, almost 15% of the American workforce was engaged in agriculture. That number is now between 2% and 3%. But multiplying what command over consumption goods the average person has by a factor of 3 and 1/2 is a pretty dramatic transformation.

There were, however, failures in that 50 year period. First of all, the improvement in the average standard of living was not smooth or uniform. There were recessions in 1954, in 1958, in 1960, in 1970, in 1975, in 1980, in 1982, and in 1991. And you know the standard newspaper puzzle, what is the next term in that progression? You're not going to learn that tonight.

There were also episodes of inflation during that period. Output per hour work, productivity of labor in the US grew rapidly early in the period and then slowed down and then may have sped up again in the last few years. A more worrying aspect of that last 50 year period was that the amount of inequality in the distribution of economic goods was getting worse.

Inequality diminished early in that 50 year period. And then from about the mid 1970s, turned around and we had a long spell of widening inequality, a bigger spread between the top and the bottom earners in the population. It looks as if that worsening inequality may have stopped in the past two or three years. It's really too soon to know.

The data are fragmentary. And in any case, there has even, in the past two or three years, not been any reversal of widening inequality. It may be that between 1950 and 2000, the incomes, the real incomes of those in the bottom third of the income distribution may actually have decreased. By the way, those are not the same people.

The people who were in the bottom third of the income distribution in 1950 are not the same people who were in the bottom third in 2000. But if you think of that as a role in society, being one of the 33% poorest people in the society, then the real income associated with that role has probably actually diminished in the past, in the past 50 years. We know, for instance, that the earnings premium associated with higher education has increased and is still increasing. That's very good for you and for us.

As a matter of fact, the US has been very successful at higher education. People come from elsewhere to go to universities in the US. We have not done very well at educating the less talented part of the population and the poor. People don't come from far away to go to urban elementary schools or high schools in the US. One of the bad things about the past 50 years is that we risk perpetuating a sort of permanent underclass.

But if the period from 1950 to 2000 was a success-- and I think despite the problems that I mentioned, that success was based mainly on technological innovation, improvements in economic policy, and good luck, in what proportions it's very hard to say. And this is, in a way, what Paul was telling you about. Some of those, many of those improvements in economic policy are probably traceable to better economic analysis, to a better understanding of the way a mixed system like ours works.

How about the next 50 years? How about the years when you will be as old as the three of us are now? No one can predict what economic life in the US will be like in 2050.

That's not because we're bad at predicting. It hasn't been determined yet. God hasn't decided how good things will be in 2050. So how could we possibly know?

But there are some fairly clear tendencies that we can talk about. For example, it's not just us, but the population of the US is aging. And that's happening elsewhere in the modern industrial world as well. There will be, 50 years from now, relatively more old people like us and relatively fewer young people like you.

That comes about for several reasons-- first of all, because of increasing longevity, also because of smaller family size, there are fewer children born on the average to each woman in modern societies. And the aging of the population also has to do with a single historical event, the baby boom, the fact that about 1950, in fact, family sizes and the size of a completed family in the US and elsewhere and the world began to rise and created a bulge in the population. That bulge, like a pig swallowed by a snake, is sort of creeping through the body politic and--

SAMUELSON: Stop there.

SOLOW: Yes, I do not intend to describe the end of that process. But before, before 2050, the baby boom will have retired. And this very important fact, that the population is getting relatively older, is unlikely to be reversed any time soon.

Immigration is an offset to the aging of the population. Immigrants tend to be younger and more fertile, have more children than resident Americans. But immigration is unlikely to occur in anything like large enough numbers to reverse the process.

Why is the aging of the population important? It's important because the working age population shrinks as a proportion of the total population. If we want to look at the standard of living at income per person in the population, we can describe that as the product of two numbers-- income per worker and the number, the ratio of workers to population.

And if the second of those factors gets smaller, as it undoubtedly will, the standard of living will tend to suffer unless something else happens. The average standard of living will fall unless-- compared with what would have been without this aging process unless something happens to change it. We will simply have fewer producers relative to the number of consumers.

There will be non-economic consequences of the aging of the population as well. Nursing homes are going to be more popular than nursery schools relatively speaking. And voters, voting will change. Old voters are different from young voters.

By the way, you want to keep in mind that this fact that I've been describing to you is, to a first approximation, only to a first approximation, independent of social security arrangements. Franco, unless I miss my guess, will want to talk to you a bit about Social Security. But the main function of the social security system is to determine how much of the national pie goes to the old folks and how they finance their access to their share of the national pie. But what there is to divide in any decade, in the decade from 2040 to 2050, for instance, is what is produced in that decade.

The social security rolls don't directly effect that. But they do indirectly. They do because the social security rules influence retirement decisions. They may provide incentives to retire earlier or later.

Older retirement would relieve the aging problem. In fact, in recent years, the age of retirement has been decreasing, not only in the US, but elsewhere in the industrial world as well. And that reinforces the effect of an aging population.

The real offset to having a smaller working population is higher productivity. We know that output per hour work will be higher in 2050 than it is now. An important question is whether productivity growth can be accelerated as a matter of policy, sort of as a conscious decision of the society. The answer to that is probably yes, although it is really impossible to be quantitative about it.

And that brings me to a question that I think you would like to talk about and I don't like to talk about, the question that you read in the newspapers or on the web or wherever. Are we on the verge of or are we already into some sort of new industrial revolution, a new economy that will make the kinds of mundane considerations that I've been talking about obsolete?

A simpler question is whether the acceleration of productivity that has happened between 1995 and this year, and 2000, whether that acceleration is sustainable for the next 50 years? By the way, even the rate of productivity growth between 1995 and 2000 is not noticeably faster than it was between 1950 and 1972. In round numbers, output per hour worked in the US rose at a rate between 1% and 1.5% a year in the years between 1972 and 1995. And in the five years or four years between 1995 and 1999, it rose between 2% and 3% a year, and even faster so far in 2000.

That's a big difference. It seems like a small difference. Does productivity go up at 1% a year or 2% a year or 2% a year or 3% a year? But over a 50 year period, 1% productivity growth increases productivity by 65%, roughly 2% by 170%, and 3% by 338%. So what you will be able to consume per person on the average in 2000 really depends in a big way on a percent here and a percent there in the annual rate of productivity increase.

Will the good fortune of the last few years continue? I don't know. Extrapolating from four or five years of observation to 50 years is not a comfortable activity. It helps if you can look a little deeper. We can look a little deeper. But the observational basis is still very slim.

Mark Twain said in Life on the Mississippi, "Isn't science wonderful? You get such a lot of conjecture on such a small allowance of fact."

And we don't-- we're lacking a good empirical basis for trying to extrapolate productivity increase. One serious investigation I know shows that outside of durable goods manufacturing, outside of that part of the economy that that makes durable goods, there has been practically no technological, no improvement in pure productivity during the past five years.

And interestingly enough, about 80% of the investment in information technology goes outside of durable goods manufacturing. Outside of that part of manufacturing, there's very small increment of productivity growth. And it is over accounted for by the sheer capital investment and improved educational status of the workforce. So there's not much left to be accounted for by improved technology.

This suggests to me that we will be lucky to achieve the same gains in the standard of living in the next 50 years that we did in the past 50 years. We would need faster productivity growth than in the past 50 years to offset the drag from aging. I think there's a chance that we'll get it.

But there is really no certainty, nothing remotely like certainty, that we will get a lot more. What this suggests to me is that we need to pursue technological improvement, not merely in information technology, but in other fields as well. It might be a good idea if somebody majored in something other than the EECS once in a while.

[CHEERING]

That still leaves us with inequality and the problem of the unskilled and uneducated. Even suppose that we can manage the acceleration productivity to offset the drag that comes from an older population, we would still have that problem of dealing with the unskilled and uneducated. The next 50 years appear, if it is a period of rapid technological innovation, could make that problem worse unless we find some way of tackling the problems of the bottom third of the income distribution. It's not clear that we have either ideas, new ideas or any willingness to do something about that. And I will leave it there and turn the floor over to my colleague Modigliani.

[APPLAUSE]

MODIGLIANI: When I was asked to join Paul and Bob on this occasion, I immediately thought or remembered a famous line from my great poet Dante Alighieri, the great poet of Italy, who tells how he got into the beginning of the inferno and there he was met-- he was lost-- and he was met by Virgil. And while they were talking, in came Homer. And then Dante says, and I was third among such genius.

[LAUGHTER]

I hope I can keep it up. Let's see. First of all, let me say that I had the privilege of suggesting the title for tonight because I thought, and I wanted to be sure, everybody would be interested. Now, everybody here must be either interested or have lived the last 50 years or must expect to live in the next 50. So everybody should be involved.

Next, let me say that in general, I have developed ideas that are similar to those of Bob, and I generally agree with his analysis his conclusions. So let me stress the few points where I have something to add. And I say they are not that many.

One thing is that, I want to point out, we have seen that the last 50 years have been exceptional in terms of growth, have seen people get a lot better off, a lot richer. I want to point out that, in effect, there is a group of people that did even better. And that is our group.

We were particularly fortunate because we had in addition to this growth and productivity, we had three things working for us. First, a stock market boom, we find that our wealth has been multiplied without our doing anything. I never expected that I would have so much wealth as I end up having. It's completely beyond my wildest thoughts.

Whatever I didn't put or we didn't put in the stock market, we put into real estate. And that is just as much, again, pure luck as not. Now, there is a slight difference that they, on the whole, the real estate has a reason for rising because land is fixed and population is expanding and income is expanding. Therefore, the value of land, particularly urban land, must tend to rise. There is a good reason.

In the case of the stock market, there really isn't any good reason. And I think and I have said many times that much of what is going on in the stock market reflects a bubble, not entirely, not entirely. There is-- let me put it this way. The price of a share can be seen as depending on the profit it earns multiplied by the profit earnings ratio, how much-- and price earning ratio, what is the price per dollar. So dollar earned times price earnings gives you the price of the share.

Now, what has happened in this period is that both the earnings have grown rapidly and the price earnings have gone up. And the growth of the earnings is partly a reflection of this very sound economy. It's a reflection of the productivity, a reflection of many things and rather acquiescent labor behavior, which is sort of allowed on this level. But the rise in the price earning ratio, which keeps going on, is not of this kind. That is the bubble.

There is no reason why as long as the earnings grow at a constant rate, there is no reason why is the price earning ratio should rise. If it rises, it is because of the bubble. And what's a bubble? It's a situation where a price, a ridiculously high price is justified by the fact that everybody expects that the next price next year will be even higher. So no matter how ridiculous it is, as long as it keeps rising, it's justified.

And this, by the way, one learns from Paul's work to some extent. And the trouble is that as-- if the process continues and the price continues to rise, it justifies the price, but the price gets more and more ridiculous. It gets more and more out of line with reality.

And we economists always of think of a famous example, the so-called tulip bulb boom or bubble where tulips suddenly-- where the price of tulips went up many, many hundreds of times. And there was no good reason. Eventually the thing collapsed because at some point, people think the price is ridiculously high. And they do-- I'm not willing to bid it any higher. And then it stops growing.

When it stops growing, it cannot hold, collapses. So I think that bubble has been-- made us rich and may present a problem for you from now on into the future. Because I think at some point, there is going to be a realignment.

The case to some extent will be true in real estate. And there the piece of luck that we have had completely destroyed is Medicare. Medicare is being paid by the young for the old. But when we were young, we didn't pay because Medicare didn't exist.

[LAUGHTER]

So you are paying for us on the expectation that somebody will pay for you. If we never paid anything and we got that incredible boom just as we were getting old and in the need of Medicare. So these three things are very hard to reproduce.

Now, however, we have done so well. And some of this, as I say, is not reproducible. So I agree with Bob that you are not likely to do quite as well, no matter what, quite as well as some of us has done. Now, of course, because of we are unexpectedly rich, we may be leaving you young people larger inheritance than we might have done otherwise. And that will help you to some extent, will carry over, but not completely.

Now we have to have that this great development in this country still is somewhat unique. Because the other major competitor, the other part of the world that has similar capacities, similar qualities of labor, capital, et cetera is Europe. And Europe is not doing anywhere as well. And why aren't they doing as well?

Well, first of all, objectively, Europe still has something like 10%, 11% unemployment rate, average unemployment rate. It depends, it varies from one country to another. But their average is still 11%.

And furthermore, the way they are moving, they're not likely to cut that down quickly. They are very happy when they grow 3%. And 3% is not much to cut into the unemployment, just enough to absorb the productivity and population growth.

Now, why are they doing so badly? Well, I think the answer is-- Paul gave it before-- because they do not read Keynes. They refuse to understand Keynes. They are stupid enough so that they will not read and understand that if there is not enough money in the economy, you have unemployment.

OK, so they keep a policy which is wrong. And they keep it continuously even to the present time. You just had an example. With 10% unemployment, the central bank raises interest rates without understanding that the way to cut unemployment is the American way-- invest, invest, invest. That's why we are doing so well. That's why they are doing so poorly.

That's, by the way, exactly what Keynes said. Investment is what determines income, OK? That's the major determiner. Now, it can be bailed out by government or private here in this country, fortunately, it's mostly private investment. That's what I think.

But that is what is driving us so high. And that's in the way of Europe. I do hope that at some point, they will learn Keynes. There still is hope. I have been fighting my way.

But I have just-- a couple of months ago, I wrote a paper explaining this. And one of my colleagues said, poor Modigliani, he still believes in Keynes. That's the European mentality. To which I replied, poor guy, you never understood Keynes.

[LAUGHTER]

Now, as we look ahead into the future, aside from these known advantages, there are some definite problems to worry about. And I would like to mention some. First of all, there is the fact of the Wall Street bubble, that when the bubble explodes, as I expect, there will be unpleasant consequences in the economy. There will be very likely some decrease in demand because consumption will decrease.

You keep reading everywhere about the wealth effect. Consumption is so high because of the wealth effect. You seldom see it, footnote it says, that is to be found for the first time in Modigliani's life-cycle. That's where the wealth effect was first mentioned in the 1950s.

Now it's become very popular. But that effect certainly, I'm sure, I believe that that is an important thing that has supported our boom, although more than supporting our boom, it has done something that's not so good, creating a large deficit in the balance of payment.

Remember that that is a problem. We have a gigantic debt. We have a gigantic deficit. That is, we spent more than we earned. We used more resources than we produced, OK?

Now, one has to be careful in distinguishing whether having a deficit or being in debt is bad, per se, from the size. The fact of being in debt is not, per se, bad or in deficit. Think of anybody like you in your age group. You are maybe who will be buying a house.

In the year in which you buy a house, your income is $1,000 and you spend $20,000. So you have your terrific deficit and you go into debt. Is that bad? No. Because against the debt, you have an asset.

The same thing is true in this country. We borrow. But we borrow to invest. So essentially, against the debt, we do have earning assets. And there is nothing per se wrong with borrowing. The problem is that if you go too far then the creditors may begin to get worried, OK?

Yeah, you're investing, but look at how big your debt is. If something goes wrong, you will be unable to pay. And that's the danger we face in our balance of payment, that it is conceivable that at some point foreigners will refuse to continue to lend us or to buy the shares of our companies, to provide the capital, because they've had enough.

And if that happens and if they want to stop bringing in money and the dollar might begin to stop appreciating and might begin to depreciate, then they may be wrong. Everybody may want to get out of the dollar before it depreciates further. And then the United States is no different from Malaysia or from Singapore-- no, Singapore did all right, but any of the states of the governments that appear to be in complete disarray. Because with further changes, if people want to get out, there is nothing you can do except let the currency devalue.

That's the only-- you have to let it go. When that happens, you have inflation. When you have inflation, the central bank will raise interest rates like [INAUDIBLE]. Investment will decline. And we could have serious consequences, including contributing to the stock market crash.

Because as people get out, they want to sell the shares they own and have additional pressure. So that complex of very high-- I mean very high-- stock prices bubble, the deficit and the balance of payment is a complex that could generate some serious problems in the future.

It need not. That is, it is possible that things would sort of quiet down. But the main way in which we could help the situation would be by saving more. Because if we save more, we can serve those investment, we can finance those investments without the need to borrow abroad. So that would be a very desirable thing.

Now, let me come to another problem which I think is a part of the long-run view. And that is what Bob has mentioned, the problem of Social Security. We do know that we have a system of Social Security which is called pay as you go, a system in which the pensions are not paid out of the accumulation that you have made.

See, in the normal system, or in my life cycle, people accumulate wealth. And they use that wealth to live when they are old, OK, to essentially pay their pension. The present system is instead, you do not build up a wealth.

You take the money that is contributed by people. And instead of putting it aside, you use it to pay pensions. So there is no accumulation.

Now, that has several consequences. One consequence is that the system is unstable because the relation between contribution and pensions depends on how fast the economy grows. If the economy goes fast, then you can get out more than you put in because there are more people to pay with their contribution then there were when you started. So you could get more money than you could put in. But if you are promised a certain return, that's like an implicit interest rate, if you promise a certain return.

And if the growth changes, then you cannot deliver the promises. And what's happened in this country and throughout most of the world is that as population growth declines, you cannot fulfill those promises because the ratio of people that pay contribution to those who get pensions changes and deteriorates. You have less and less people paying per person taking a pension. That is sure to create problems.

Now, how much and how bad will depend on what we do about it. The present administration has no program to handle that. That is, it will put in, throw in the surplus of the budget to support Social Security.

But that will not get you beyond the middle of the next century. By that time, approximately, there will have to be something like a 50% increase in the dues in the what you have to pay in the payroll tax or a cut in benefits.

And here is the point where I have something to offer. I've been working now for a couple of years on finding a solution to this problem and find that the solution exists and it's really rather simple. The solution consists in creating a so-called funded system. A funded system is one in which the contributions, instead of being used to pay pensions, are used to accumulate wealth.

And then when you retire, that wealth and not the young people, but that wealth pays your pension. Now, once you have been able, you've made the change, you can see that this system is far better. Because in the first place, it is cheaper.

We have figured out that under the pay as you go, by 2050 or thereafter, you will have to pay about 20%, 21% contribution instead of the 12% of today. With our system, you would pay only about 7%. So it would be able to cut, get over the crisis, and cut contributions very substantially, by about a third.

And furthermore, a funded system is less sensitive to variations in growth. It's completely, well, largely unaffected by population growth because population affects the picture because they are young support the old. When the old are supported by their capital, they don't care how many young people there are.

Now, you have to understand the moment, how that fits into the picture that Bob has given and which is very commonly accepted. The idea is that, how can you avoid getting poorer or paying less pensions if you have less people, more old people to supply? Because, he says, that's the pie. If you've got more for them, you've got less for the others.

Well, the answer is that under our system, the pie is not fixed. The pie precisely depends on what you need. If you have many old people, you will have large accumulation from the past, which will take care of it. They may be to the point where the accumulation, the fund, will be decreasing because they'll pay out than it gets. But that's all right.

Paying out more than it gets simply means that you would be liquidating some assets. Society as a whole, which is not growing, would need less assets anyway. So the thing would largely take care of itself.

So this is, I think, a kind of possibility that gives us hope. I mean, obviously, I don't have time to go into details. But I should have brought with me the website where you can find this. By the way, I can tell you, if you look in the website under MIT and under Franco Modigliani, you will find there that there is the latest version of my plan. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

SOLOW: Thanks. There are a couple of microphones set up, at least in that aisle and in that aisle. I can't see if there-- I think those are all that there is. But we're happy to have some conversation with anyone who has a question or a pronouncement or a theorem. Who knows?

AUDIENCE: You'd have to be very brave for a pronouncement in this group. A question to all of the panel has to do with aging and also your solution, Dr. Modigliani. It seems as if you're making an assumption that the aging will have an effect which is bad.

You were mentioning that retirement age is going down rather than up. You know, but look at the three of you. In many parts of the United States at least, people may have retired, but they may also still be working. The fact of people being, of older people being healthier and healthier, I wonder it's a really-- and I just don't know if, you know, I'm just asking because I don't know. Has there been any work done to really try to quantify that aging effect? And then I'll look at your website for the second question.

SOLOW: Well, let me-- I think there is a little illusion here that is shared always by people like us. By us I mean everyone here in this room. We're people who on the whole-- well, let me back up a minute and say, one obvious way for a society to deal with this aging fact, demography, is to prolong the working life. Just as was just said, we are living longer.

We're living-- we're having healthier old age. Why should not the working life be prolonged? People like us who like our work, who rather don't like the notion of retiring, we want to hang on to the office and continue to work, that seems a little more obvious than it is.

The society is full of people who do dull work and don't like it. And they will not be happy to be told that, well, the way we deal with this is for you instead of retiring at 65 or more likely 62 or 61 as you had planned, you will, of course, use your healthy years being a clerk in a department store for another five or 10 years or for doing one or another kind of work that's not so pleasant and not so rewarding.

I think it's inevitable, actually, that the working life will be prolonged in the US and elsewhere simply because people live longer and are healthier. And the way to deal with the productivity problem that emerges is to prolong the age of retirement. I think the scheme that Franco was describing, the connection between what he was saying and what I was saying is that this extra accumulation of capital that comes with the funded system is precisely what gives you the extra productivity that's needed to support--

SAMUELSON: Exactly.

SOLOW: --a population, a smaller fraction of which is working. The amount of work performed by the population measured in hours will diminish. The decreasing age of retirement is not an illusion. For people like us, it is.

But for people who work in automobile factories and now live in RVs, recreational vehicles in Florida, it is not the case. So something like the extra capital accumulation is what we need. Franco, did you want to add something to that.

MODIGLIANI: Well, I'll just add one thing. First of all that every thinking person agrees that the least you want to do is you want to give incentives to work longer. Whether or not you make it mandatory, you want to give incentives.

And that's not an obvious thing. I mean, let me remind you of the example of the folly of my former country, Italy, where the reasoning was once you retire, you have a pension.

SOLOW: Do you want to take a turn on this question?

SAMUELSON: No.

MODIGLIANI: You shouldn't work anymore because otherwise you get richer. Therefore, if you work, we'll tax it heavily. That's completely the wrong reasoning. If you work, the fact that you get richer, fine, that's your incentive to work longer. So that's exactly we should provide that kind of a thing.

We might also have some shift in the age, in the standard age when you retire in order to maintain the relation between-- see, this is particularly important with respect to life expectancy. Because aside from the getting older because of the smaller number of births, you also have the fact that longevity is increasing. And longevity increasing requires additional contributions in some form. And one way to cut that is by lengthening by time the retirement age to life expectancy.

SOLOW: Why don't we try the other microphone?

AUDIENCE: Professors, in his remarks, Professor Solow talked about the success of American economics and the sustainability of rapid growth and productivity. This is, to me, a global question.

The model that was taught to the word by Ford in the beginning of the century, and by the American society in its whole, is a model that is sustained by a very high level of consumption of goods, personal transportation, that is cars versus bus, and the production of short-lasting products instead of quality products and what. America is the first country in the world has number of cars per capita that is a success. But even the most polluting country in the world in terms of the amount of energy that's used per capita.

My question is now, what will happen in the next decade, the next 50 years when energetic resources will be more crucial and costly and when some rapidly growing countries China, for instance, will ask for the same level of welfare of US? What will happen to global economics at that point? And the second question that--

[LAUGHTER]

--what can be done-- sorry-- what can be done to develop a sustainable economic model in the next five years?

SOLOW: Paul, you want to tackle that?

MODIGLIANI: I didn't understand a word.

SAMUELSON: Well, one person, one question. It's obviously the case that the US, with its early high standard of living, has been plundering the exhaustive and exhausting resources at a much faster rate. And if we are successful in other parts of the world in raising levels of standard of living to the US level, that will mean a billion Chinese are plundering at the American rate, a billion Indians will be plundering at that rate. Scientists will always be finding new resources.

And in the age after nuclear, probably scientists can do a lot of winning of the battle. But there still is the second law of thermodynamics. And there still is some limitation. And so it will become very important not to have SUVs versus efficient cars just because people want them.

And this is one of those places where you can't leave it to laissez-faire. Because if it's left to laissez-faire and I want an SUV, I'll have an SUV. But my freedom ends where your nose begins as I swing my cane. And--

[LAUGHTER]

--we're all breathing the same molecules. Julius Caesar died. And I'm breathing some of his molecules. So we really are interdependent. And I think there will have to be, in 2050, when, instead of our having 23% of world output with only 5% of the population, we will have something like 9% of world output and there will be a lot more demands on it.

And so this doesn't mean that we can't use a pricing system. We actually are using a pricing system to ration out pollution. But we can't rely only on the pricing system. We need the common rule of the road.

AUDIENCE: Professor Samuelson, in particular, but any of you who would care to answer, I didn't hear any of you speak of the interaction between, on the one hand, globalization, which I think does bring, what you were speaking of, Professor Samuelson, the bigness being the enemy in some sense, and the interplay between that and democratic institutions, which are very much more on a different scale and no longer related in any direct way.

SAMUELSON: I thought meeting with students someone might bring up the question that was bothering the mob in Seattle who were protesting against the World Trade Organization because the low prices at which I can buy at Wal-Mart are as low as they are because somebody in China is making a very low wage.

And this takes me back to an election in 1962 in Massachusetts. There was Professor Stuart Hughes who was a very liberal professor of history ran for Senate. And he ran against Teddy Kennedy, the reactionary, right? And he was in favor, Hughes, a friend of mine, but not a student of mine, he was in favor of a $7 minimum wage at that time.

At that time, it was about $2. He multiplied it by a couple. And I said to him, you know, the traffic won't bear this. We won't be competitive with other countries. He said, you don't understand, Samuelson. I'm for a $7 minimum wage every place in the world.

[LAUGHTER]

And I said to him, that is the cruelest remark I have heard in all of my long lifetime. Because a $7 1962 real minimum wage US purchasing power would have caused, of the five billion people then alive, about 4 billion to die of unemployment and starvation. So the requisite problem-- this is what makes economists such awful people, you're even awful to your own children. You say these practical things.

What you have to ask is not do I want a poor little girl 12 years old in China to be getting the wage that Walmart eventually pays and, of course, the answer is almost nobody but a few sadists would want that. But what are the alternatives if you don't have globalization. How has Africa fared being outside of the globalization system? What converted Hobbes' jungle, where life was short, nasty, and brutish, into the present world? It was Newton.

It was the age after Newton. And there is no way that the consumers of Walmart, given their quantum of altruism, are going to give up their comfortable standard of living in order to have a unilateral transfer, a gift, to those workers. And so you have to ask yourself, in the next 10 years, will the emerging market countries have an upward trend in real wages for their people, earned by their people in the exchange system or not?

And a simple-minded support of globalization under all conditions is wrong. But a simple-minded rejection of it-- now, I said I was going to be nonpartisan. But I do have to say, I don't agree with candidate Buchanan.

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE: I have a question for Professor Modigliani. You talk about changing the pension system from the current system to a system where you fund, basically, your pensions through time, you start investing them now. One of the places where you would invest those pensions would be the stock market. And earlier in your remarks, you talked about sort of the irrationality that's inherent in the stock market currently.

MODIGLIANI: Yes, yes.

AUDIENCE: So I'm wondering if you could elaborate a little bit on and how you would insulate, how you would insulate the funds for those pensions from the stock market volatility and how you would make sure that people actually do get their money at the end of their lives.

MODIGLIANI: Let me answer briefly because that's the time we have. First of all, let's be clear that in my system, all the money that's contributed goes not into your own portfolio, it goes into a common portfolio. The idea, to be nonpartisan, of Bush that it should go into your own portfolio is completely wrong because it makes Social Security into a gambling casino, OK, exactly what it does.

[APPLAUSE]

You are forced to save. You should know what comes out. And that requires defined benefits. Now, how do I invest the money that's accumulated? Essential in a portfolio that mimics the economy composed of the same way as the market.

Now that doesn't prevent the market from some movements. And right now, it's too high. The specific problem that it is now too high I handle the following way. Before my reform is accepted, there'll be plenty of time for the bubble to deflate. Then, when it's deflated, we will invest.

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE: I'd like to come back to the globalization topic. The reason, at least from my point of view, is that many of the products you can buy in Wal-Mart are so cheap is because low wages are very low in developing countries, but a reason for that is that, in large part, because of repressive governments, such as in Indonesia or in Latin America, for example. And the US and Europe, to some extent, supports these governments, actually nurtures these governments.

Because usually corporations get a higher yield out of a dictatorship. So in a sense, there is some unfairness there. Because these repressive governments actually, well, they attack unions and they attack labor movements. And so this is actually a very unfair form, reason why these wages are so low. Because the labor, power of labor in these countries is very weak because of violence. And I'd like to know, hear what you have to say about that.

SOLOW: Well, let me take a shot at that. I want to separate two things. The fundamental reason why wages are low in developing countries is because productivity is low in those countries. That's far more-- if you were to-- if you were to classify poor countries or all the countries of the world in terms of the degree of democracy that's available, the correlation between that and earning power is very small.

The fundamental reason for the poverty of underdeveloped, undeveloped countries is their low productivity. Bad governance, dictatorships, tyrannies of one kind or another surely make things worse. But if we're going to be-- deal rationally with the world economy, we have to distinguish between the globalization in the sense of open trade where possible, migration possibilities, free movement of capital from places where there's a lot of it to places where there's a little of it.

That has to be distinguished from dictatorship, tyranny, lack of democracy. From my own point of view, I think that over the past 50 years, American foreign policy has been much too tolerant of dictatorships and repressive governments in the third world. And I have certainly-- and I imagine all of us here have opposed that politically.

But the step from that to saying one ought to restrict trade with poor countries is a bad step. It's an illogical step. Generally it's the representatives of workers in poor countries who want open trade, not oppose it. So I think we should try to keep the political side of this from the economic side of it separate intellectually. Because otherwise, it's not possible to think rationally about those things.

SAMUELSON: I would not minimize the harmful effects upon future standards of living of repressive government. It'd be very difficult in a Nigeria, even though it had oil, in the Congo, rich with metals, to develop at all. And when colonial powers moved out, at the beginning, they were not repressive governments. But without the repressive governments, they didn't spring instantly into high wage countries.

If you just begin the process and the international division of labor can help when there isn't a repressive government and it won't help much where there is such repressive government that nobody feels secure in doing any saving, nobody gets the result of their productivity, there is no way of sending students to get advanced training, so there always are an eclectic number of explanations to each problem. That's why economics is boring. But to me, that's why it's interesting.

AUDIENCE: Professor Solow, this is mostly for you. With the new productivity numbers between 2% and 3% annually, what do you see as the correct Fed's position on interest rates, which is currently at 6.50%? But historically speaking, that's over-inflated. What is your opinion?

SOLOW: About interest rates here in the US or--

AUDIENCE: Yes, interest rates here in the US.

SOLOW: Well, the Federal Reserve, the central bank in the US has, I think, in formulating and executing monetary policy has been well-aware and reflective about the growth of productivity. They may occasionally have been overoptimistic, in fact. But on the whole, I think that as-- are you ready for a complicated answer here?

AUDIENCE: It's my job. I can take a complicated answer.

SOLOW: There is a real danger that-- a real possibility, I think, that we are managing this period of rapid expansion with little or no inflation as a result of an unexpected acceleration of productivity, which has not been fully reflected in wages and therefore in-- and therefore prices are able to move along at a relatively low level. I think the Fed has performed extraordinarily well in seeing that this lucky period-- if it's luck-- is translated into high employment and increasing production. They are nervous, as we're all nervous, that the timing, when this particular lucky period ends, the timing is going to be very difficult to get right. So hold your breath.

AUDIENCE: OK.

MODIGLIANI: Can I just add a word to this? I think the Federal Reserve on the whole has done a really excellent job. They may have been lucky to some extent, but they have shown the right mixture of courage and restraint. I think they're really quite good. And I think-- when I said before that Europe has a lot of unemployment and they don't understand Keynes, one of the manifestation of this is that the European Central Bank has only one instruction, avoid inflation, whereas the American Constitution says, see to it that output is large as possible subject to the condition that there should be minimum inflation.

And that makes a good difference. And I think we see that policy being pursued here. And you see the policy of saying no inflation leads to very tight and high unemployment. Because then you're sure. If you've got 20% unemployed, then you don't have to worry about inflation.

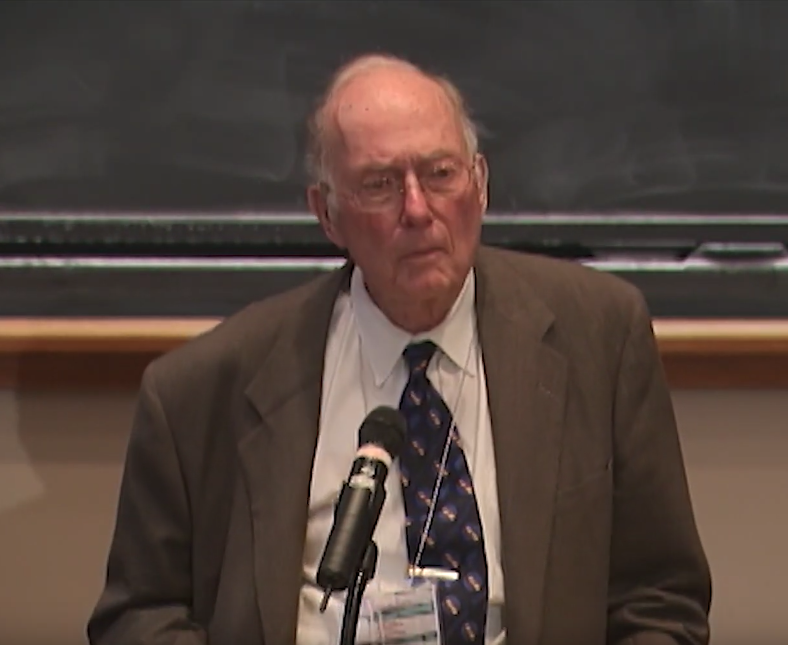

SOLOW: I'm afraid we're going to have to-- to stop now. And although my understanding is there's going to be some food and drink outside after we're done. And I at least, and I imagine my colleagues, are happy to stand around and chat some more. But the introductions are going to go in flow up hill here. I would like to introduce to you Marty Zimmerman, who is the Vice President for Government Relations of the Ford Motor Company, is a PhD in economics from this institution, and is, in large part, responsible for the program of which this evening is the start. Marty.

Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

ZIMMERMAN: Thank you, Bob. I was hoping you wouldn't introduce me and then I could use my line a la Admiral Stockdale, who am I and what am I doing here? But having introduced me, I just want to express my thanks to the panel, to professors Samuelson, Solow, and Modigliani for a really interesting evening.

I'm thrilled, personally, to be part of this. As Professor Solow has said, I was a student mid-century here, mid-century in terms of the between the '50 and the 2000 period. And I derived tremendous benefits from studying from these gentlemen.

I think we all got a taste tonight of what an enriching experience that was. And I don't mean solely in Franco's terms that we all found ourselves wealthier in the year 2000. Although as the developer of the life-cycle hypothesis, do you feel that you consume too little?

MODIGLIANI: That's right.

ZIMMERMAN: Anyway, Ford Motor Company--

MODIGLIANI: I'm going to go consume more outside.

[LAUGHTER]

ZIMMERMAN: But Ford Motor Company is really delighted to be able to sponsor this series of Nobel laureates. I think this was a terrific kick-off. I hope, but doubt, that we'll be able to sustain this level of quality as we go through this series. This is one part, and really a small part, of a very deep and evolving relationship between Ford Motor Company-- by the way when I come to Cambridge, it always helps recognition if I mention that Ford owns Volvo.

So that's-- but it is really only one part of a, as I said, a deep and evolving relationship involving research and teaching, which I am excited about. We are-- I know at Ford we're very excited about it. And I believe our counterparts here at MIT are excited because we've done some great things. And we look forward to doing even greater things in the future.

My second role tonight is to tell you that there is a reception outside. Since we've had such a tremendous turnout-- and, in fact, I was told there were overflow crowds in several parts of campus-- we've moved the reception outside. I trust the weather is cooperating. So, again, thank you all for coming. And, again, thank you to the panelists for a truly great evening.

[APPLAUSE]