School of Humanities, Arts and Social Science (SHASS) 50th Anniversary Colloquium, “Asking the Right Questions” (Session 2) 10/6/2000

[MUSIC PLAYING]

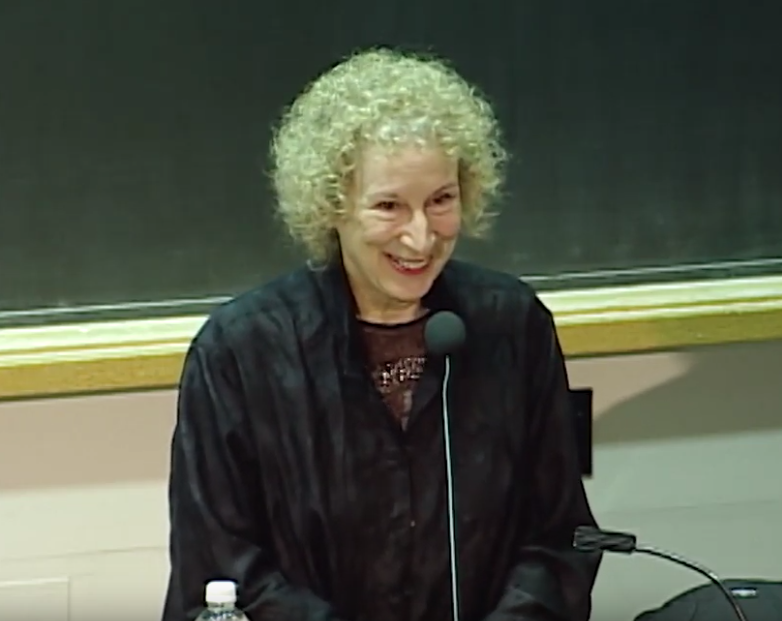

HARRIS: Good afternoon. Good afternoon. My name is Ellen Harris. I'm head of music and theater arts here at MIT, and I'm delighted to be able to introduce the second colloquium celebrating the 50th anniversary of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. The colloquia, in celebration of the anniversary, are all composed under the title "Asking the Right Questions," which became very important in the question period following the first colloquium where we learned that one needed to ask the right questions. I believe to a certain extent that's what art is, is asking the right questions, and we will be doing more of that this afternoon.

The question in the title of our colloquium, which is "How Do Artists Tell Their Stories" in itself, I think, asks for further questions-- whose story? The artist's? If not, whose story? What kind of story?

50 years ago at MIT, Bernice Abbot created photographs that told stories about wave force magnetism and the nature of light. And the high speed photography of MIT Professor Harold Edgerton depicted stories about motion and impact that had never been told before. The counterpoint of art and technology at MIT tells us that art and design are inextricably linked, that a fragment or a flash of insight contains a story as much as a lengthy narration, and that art tells stories about itself, about the world, and about our place in it.

The artists on today's panel deal with questions, fragments, stories, and narrations of many kinds. I'm reminded of MIT's famed mechanical engineering contest where students are given a box of materials and told to build a specific device. Artists' toolboxes, in addition to such grammatical tools as rhythm, phrase, tempo, meter, which are things all of our panelists deal with in different ways, their toolboxes in addition are full of questions to ask and questions to answer. This afternoon we will explore some of those.

By way of introduction to the panelists, I would like to share with you some of their words about their work that I found relevant to our discussion this afternoon. I refer you to the program for their biographies and for the honors that they have each received, which are the length of my arm, and I will not repeat them. But you can find them in your program. The reason I do this is because this panel is somewhat odd.

[LAUGHTER]

In the sense that all of the other panels, the panelists get to talk their work. What they are presenting is their work. They haven't been asked to tell us how they do their work, or what their work means, but rather they present their work. One of the things we're going to do this afternoon in order to make that clear is that each of our panelists will present something of his or her own work in the course of their presentation so that they will not simply be asked, as if we had a comic here and asked the comic not to tell any jokes but only to explain what a joke is, and we will not do that to our artists this afternoon.

[LAUGHTER]

Our first speaker will be John Harbison, an Institute professor at MIT, who in 1995 gave the James R. Killian junior faculty achievement lecture. The title of his lecture was "The Beauty of Senseless Objects in a Market Economy."

[LAUGHTER]

He spoke directly to the spirit of inquiry and of risk taking that the creative process demands. He talked about the courage to birth and honor an idea. He spoke of the generation of a composition, and he did so, interestingly, in a series of questions. He said, what starts the piece going? What makes you begin? Where do you recognize the beginning, and what happens from that point to the point that we've just experienced?

The question then becomes, what are we looking for? And what stops us? What is the thing that happens in our minds that makes us think that we want to pursue some sort of idea with the avid quality that really is necessary to come out with something at the other end? And as he went on, he spoke of humility in the face of an idea, saying the composing enterprise is to make a pattern which has its own logic, and which carves out this space in the air in some way that is at least unique to the event, whether or not it sounds like the composer or not.

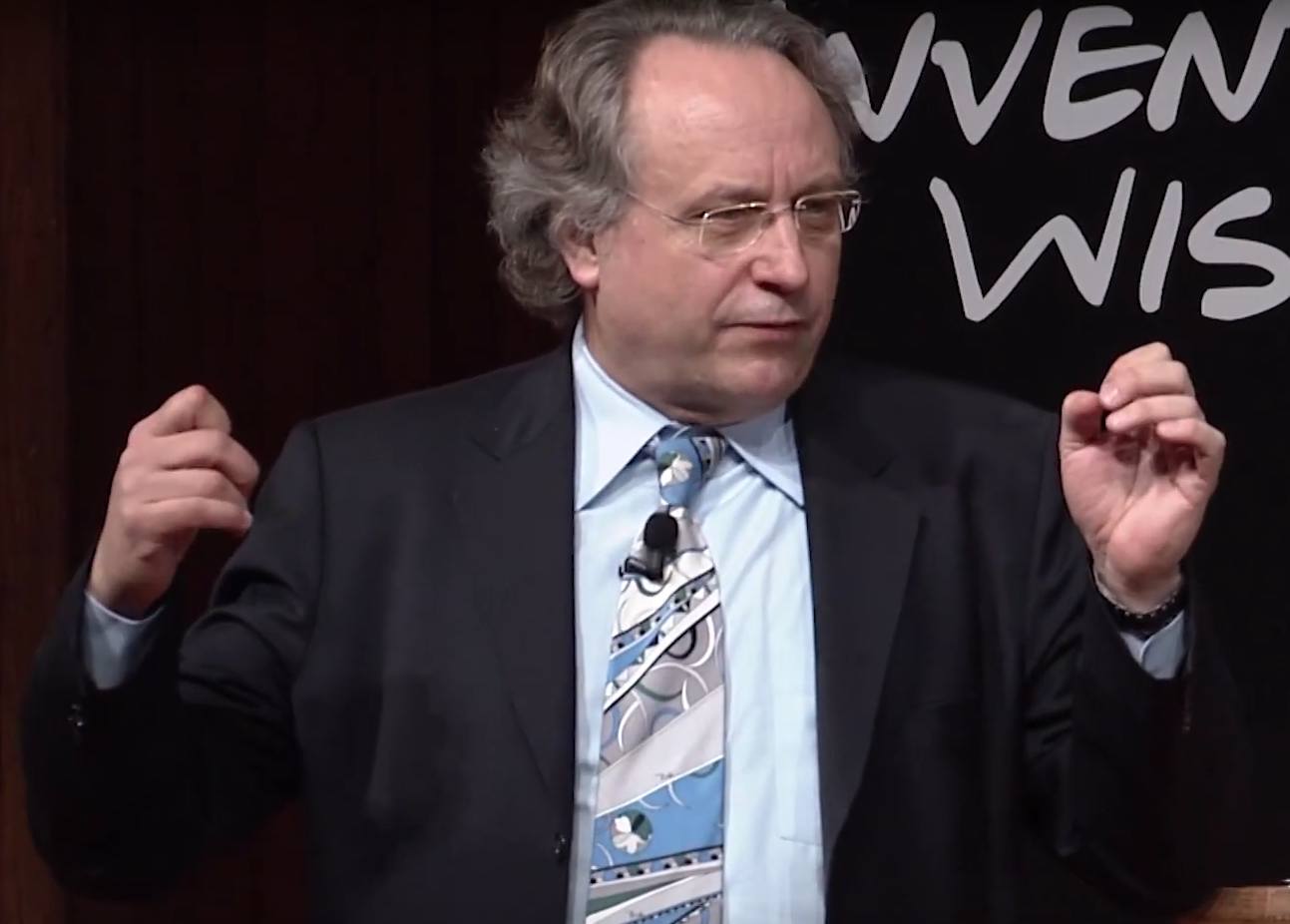

Our second speaker will be Anita Desai, who's professor of writing at MIT. In her fiction she balances idealism and disillusionment, dreams and failures, and her prose is luminous and unflinching. She spins a counterpoint of cultures that grows out of her own eye for detail that provides the readers' imagination with an expansive and comprehensive view.

In 1994, professor Desai contributed an introduction to the Turkish embassy letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague, who lived from 1689 to 1762, which is my period of research. Her sympathetic description of Lady Mary's success as a letter writer in a cross cultural situation may perhaps-- and only may-- provide some insight into Desai's own creative process. She wrote in that introduction, Lady Mary proved a traveler of a very diligent curiosity. I like to think that that's what all artists are, are travelers with a diligent curiosity.

And the reason why the embassy letters have survived the years may be that in traveling to the east, Lady Mary was able to break away from the rigid confinements-- mental, and intellectual, as well as physical-- of her own society, and showed herself exceptionally open to new impressions and points of view. This gives her letters an immediacy and vivacity that remain as fresh as the mosaics on the ancient monuments that she saw, and the eastern gardens that gave her such delight.

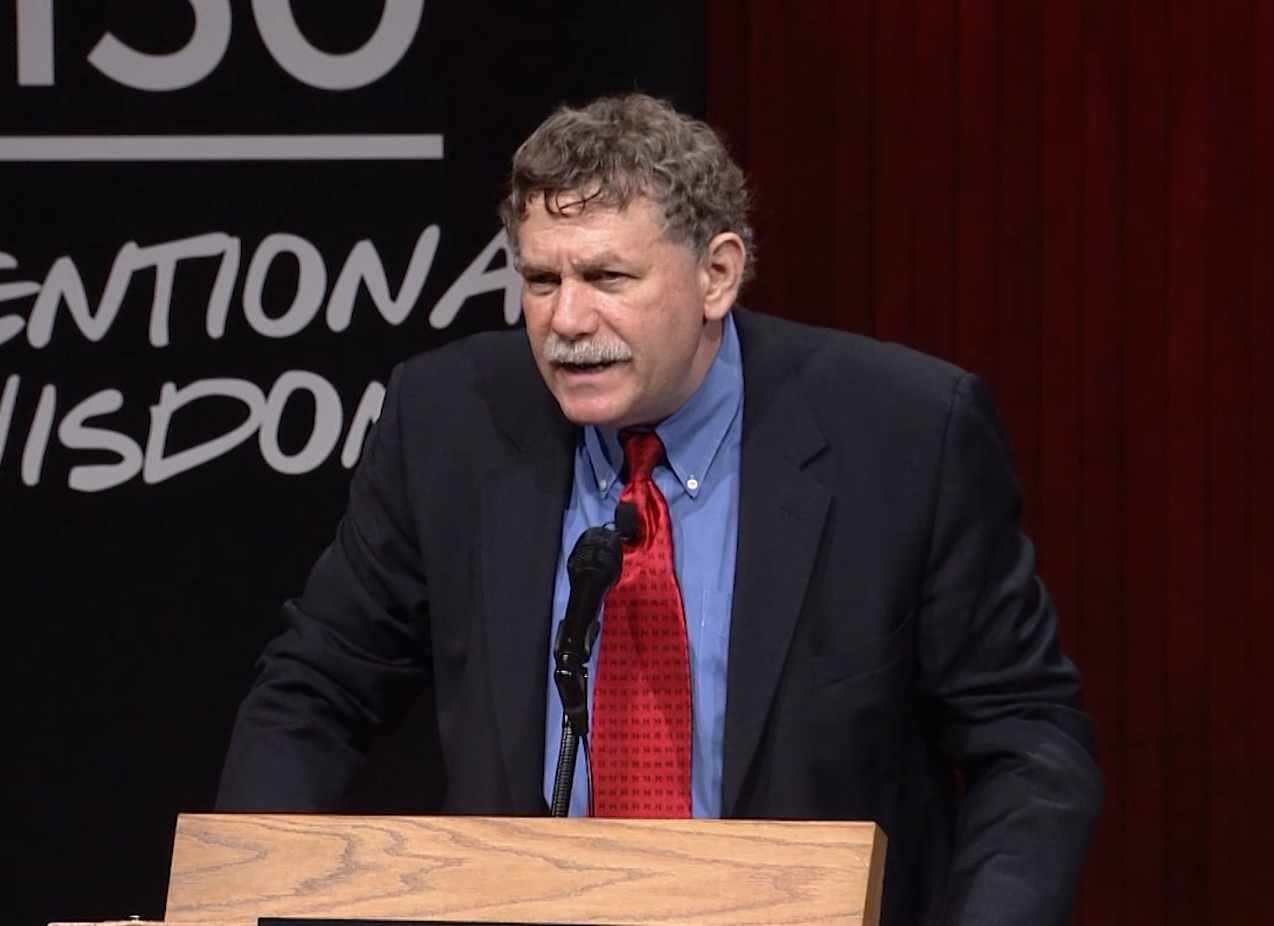

Our final speaker today will be Louise Gluck, a professor at Williams College. And in her 1994 Book of Essays, Proofs and Theories, she writes of the work of poetry. She begins her essay, "Education of the Poet," with these words, "The fundamental experience of the writer is helplessness. This does not mean to distinguish writing from being alive. It is to correct the fantasy that creative work is an ongoing record of the triumph of volition, that the writer is someone who has the good luck to be able to do what he or she wishes to do, to confidently and regularly imprint his being on a sheet of paper. But writing is not the decanting of personality." Again, the question is, whose story?

"And most writers spend much of their time in various kinds of torment-- wanting to write, being unable to write, wanting to write differently, being unable to write differently. In a whole lifetime years are spent waiting to be claimed by an idea." And remember, John Harbison wrote about accepting an idea even if it's not like the composer. The only real exercise of will is negative. We have toward what we write the power of veto."

This afternoon we will hear from our three panelists in that order-- first John Harbison, than Anita Desai, than Louise Gluck. They will each speak from the table. We are going to have a cozy setup. And after the presentations we will have a discussion where we will welcome your participation. We urge you to let us know that you want to participate so we can get you a microphone. Please help me to welcome our three distinguished panelists for the afternoon colloquium.

[APPLAUSE]

HARBISON: Well, it falls to me to begin, and I want first to say that I'm glad to have been invited, particularly in the company of two fellow artists whose work I have admired a long time. It was a nice occasion to reread some of their work, though I don't know what it's going to do for what I have to say. And I want to begin with a musical example that's something I suggested to Ellen as a possible mode of commencement. In doing so, I'm mindful of a remark quite often made by my teacher, Roger Sessions, that discussions of music without music are essentially akin to pornography.

[LAUGHTER]

They awaken the appetite, but without any real realization of said appetite. So I'm going to play five minutes of music from a recent composition, which I chose partly because its obvious relationship to our subject matter, how we tell our stories. I begin, though, with a caution about how musicians tell their stories, because I am going to play five minutes of an opera, but we don't really musically most of the time tell our stories with the aid of words, or sequences of events, or any mimetic kind of imitation of nature. But rather, we tell our stories in a more esoteric way through the movement of harmony, through the identity of motives, and melodic ideas, through associations, through contrasts both large and small-- all kinds of storytelling methods which really are much more the stuff of music than what we see and hear out the foreground of an experience of opera, or of anything that involves the stage.

So that what you're going to hear is five minutes of a very large piece of music, a piece of music which for me is hanging together and telling its story much more on the levels of abstraction that I've just suggested, rather than simply the following along of what is going on in the piece. That is to say, the drive of this narrative is in the notes and in the relationship between the notes. And it happens to synchronize, I hope, at the right places, with an action and with a story. And I think an operatic storyteller hones their skills as much as anything in becoming very precise about the notes, and about the way that they influence and affect each other.

With that said, I'll just tell you what the little snip of what was I think somewhat pejoratively described as a vast opera will be. This is from the beginning of the second act of the opera, and I think I can't take the time to fill those of you in on Great Gatsby's plotline, though there were two teenagers reading it next to me on the subway just the other day, and they were discussing it in terms which I found extremely discouraging.

[LAUGHTER]

But I will just say that at this point, Daisy and Gatsby have renewed their five-year-old affair. She is by then, however, married, inconveniently enough. And in the second party scene of the opera, Tom and Daisy show up at a Gatsby party for the first time. And in the scene that you're going to hear, you'll hear what we would call first ambient music-- that is to say music played by a band at a party, which is a period flavor. Though in disguise, the motives and the basic harmonic drive of the piece are still kept going, even in this music.

One of the problems of the piece being movement from ambient music into the music that I write, which is substantially most of the music that I normally write, whatever that is, because as you heard from the thing Ellen quoted, what I normally write isn't that clear to me.

[LAUGHTER]

But nevertheless, moving from the ambient music in which Tom and Daisy are ostensibly introduced to Gatsby-- of course, he knows her already-- we then get an account by Gatsby of his early life. Now, one of the reasons I chose this passage is that this account in this form doesn't occur at all in the novel. It is something which is, I thought, important in the opera to do frontally. It is a stiff dose for people who want Gatsby's voice and persona to remain misty and indistinct.

And I find the people who dislike this opera the most are the ones that remember the book in the most hazy, romantic way. And the friends of the opera tend to be either rabid Fitzgerald readers and scholars, or people who have forgotten the book almost completely.

[LAUGHTER]

But at this point, Gatsby delivers this account of his life, which is mostly phony, to Tom, to his girlfriend's husband, who is getting his first dose of Gatsby, and who finds him a rather outlandish figure. But at the same time, Daisy occasionally joins in in suggestive lines in this narrative, dreams off into them in a sense, establishing a connection between them, which is not yet really known to Tom. In fact, the action of the scene is the realization of Tom's beginning of jealousy or suspicion about Gatsby and Daisy.

And at the end of the monologue, the little very brief account of Gatsby's life, you'll hear a kind of return to the ambient music at the point when Tom says, you renew your old acquaintance with Gatsby, which they've just established, and I'll introduce myself around. He already has his eye on an actress who he then goes off and dances with. And you'll hear the ambient music return, and at that point in the composition I think you'll be able to hear it in its best, clearest form, the kind of transitional issue between the stuff of the opera, which is the music in which I kind of live and work, and a sort of synthetic period evoking kind of composition.

People come out of this piece saying, gee, it's great hearing those old songs again, which is kind of flattering because they are old songs that I composed.

[LAUGHTER]

And other people come out of the opera saying, you know, he really can't write melodies, so it's wonderful he at least has those old songs.

[LAUGHTER]

Which, of course, is quite literally impossible, that is if one can compose a melody in one idiom, you can in another. But, of course, this is part of the wonderful process of sifting, which I think all of us up here on stage know about in terms of the things we put out there. So let's play the five minute example. And then I'm going to go on from it to comment a bit about opera in relationship to other narrative media, because, of course, in the adaptation of a novel this is one of the things that immediately becomes an important subject to think about.

And if back there the level should be up, I'll point up, and if it should be down, I'll point down. And if it's wonderful, I won't point.

[MUSIC - "THE GREAT GATSBY"]

(SINGING) It's Gatsby. Where did you meet him?

I'm so curious. [INAUDIBLE] in the South.

I'm delighted you dropped in. The party has just begun. Mr. Buchanan, [INAUDIBLE] you. You know my wife?

I do.

Let me introduce you to my guests.

These things excite me so.

Look around. You'll see the faces of people you've heard about.

Don't know a soul here.

You must know that lady.

And adore me.

And the man standing next to her, the director. Daisy Buchanan and Mr. Buchanan, the polo player.

No, not me. I'd rather not be the polo player.

Tom, don't be so sensitive.

Gatsby, this is quite the place. Are you in business?

You might say so. Came from wealthy people in the middle west, all dead now. Educated at Oxford, a family tradition.

What part of the middle west?

San Francisco. San Francisco. My family died. I came into money. Near delight, a young raja in all the capitals of Europe collecting jewels, hunting game, painting pictures.

Trying to forget something very sad from long ago. From long ago. From long ago. Long ago. Daisy, this fellow's priceless. Let [INAUDIBLE] a great relief. I tried hard to die, but seemed always to bear and enchanted life. Enchanted life.

My two detachments held a fortune in divisions for three days. Decorated by every Allied government, even little Montenegro. Montenegro. Montenegro. Montenegro.

Amazing. He actually has a medal.

Of course he does.

His stories make your head spin. Daisy, you and Gatsby, he knew your acquaintance.

I'll introduce myself around.

Go ahead.

And if you want to take addresses, here's my little gold pen.

[INAUDIBLE] I'm doing fine [INAUDIBLE]

HARBISON: Okay, that's the five minutes. Now, what you heard at the end is the band singer had come back on. Now, the musicians and the stage band love the reality thing of taking a break in that scene, which of course all my musician friends really enjoy too. They actually leave the stage. I don't know what they do when they're off stage, but it's kind of a moment which also helps to define, I think, the two musical realms that are going on here, that the ambient music and the music that expresses the characters are both different and linked by these common sort of motivic and harmonic threats.

It is a very different thing-- it's one of about 400 things that are very different about the adaptation of this novel-- to have Gatsby actually express frontally this particular narrative, particularly to his rival, his rival to be. In operatic terms, it's very useful in setting up a kind of pre-confrontation, which in the plaza scene will be a much intensified.

It also serves another purpose, which is it gives a kind of voice to what is in the novel a very shadowy rumor kind of texture. This is a kind of sideways sort of thing that a novelist can do, which is much less the province of the operatic character. I can do things like that in transitions, and orchestral passages, and wordless passages, but when the characters speak they have to back it up either in a phony way, as Gatsby does, by putting out a lot of details which are not real, or at least in some way that they are heard by someone, or even in a monologue heard by themselves and made responsible for certain kinds of emotions and feelings directly between them and the audience.

In opera we can't choose with anywhere near the variety of a novelist or precision a narrative voice. One of the reasons that I got rid of Nick in his narrative function is that this is not something which is-- in my experience with opera-- a terribly effective way of hearing and experiencing an opera through a character. In a novel, it can be a very rewarding journey to be listening to the voice of a narrator. In opera, you're listening to the voice of the composer who is narrating these events. And unless the composer takes those events in hand in terms of pacing and essentially deciding what all the characters say, there really isn't enough focus in terms of where the audience should be coming in.

The audience is in on everything. There is no real way to shadow things out, or to feather things out so that you almost see them. Certainly with the staging you can kind of almost see a scene, but when the music happens and people sing things, they sing them. And one of the problems that I had, of course, with presenting Gatsby onstage is the cherished image of a hero you don't know about. And I had to almost immediately, from the very first thing that he sings, establish that's not going to be how it is, because this is an opera, which caused many people to call me with magic bullets from all over the country.

You know, it's amazing, opera seems to be something that everyone knows how to fix.

[LAUGHTER]

But one of the things that I heard is, if you just get rid of a scene where Gatsby is seen consorting with Wolfsheim, then we may be able to retain our illusions about Gatsby. Well, yes, you will, but you won't have confronted one of the most important things about this guy, which is that he's also a proto gangster. And if you put him on stage and show him consorting with Wolfsheim, you give body to a very different character than that nursed by someone who's read the novel and filtered out the details they don't want to deal with.

That is to say, on stage and in a voice, you deal with all the details. The good side of putting people on stage with voices is that because they sing, there's no such thing as an unsympathetic character. If you're a novelist, maybe you want unsympathetic characters. And certainly in the originals of things that are adapted to opera, the villainous people, the people who are not very nice, are able to be much more not nice than they are in opera.

One of the things I liked about this quality in Gatsby-- well, when I started this project my mother called up. She said, you're writing an opera on a subject which doesn't have a single sympathetic character. I said, well, yes, but they're going to sing.

[LAUGHTER]

And that will change the way they're perceived. And also, operatically, I did change them. I made Daisy much more a kind of romance novel reading person with a really, at the very least, kind of histrionic side. And even Wolfsheim, because he sings, he's very rounded. People with voices present somehow dimensions to you that, because of the sound of the voice, they don't have in any other medium.

I always think of Rigoletto as my favorite example of this. There's a villain in there named Sparafucile. Well, this guy is a contract killer, and he does nothing in the opera but kill people and set them up to be killed. And yet, the way he is set by Verdi with this remarkable sort of aural image that he creates for this guy, he's fascinating. He lives in a way that he couldn't possibly if he was not surrounded by this particular sonic world of his voice and his instruments.

And this is the narrative faculty in opera which I think is something that opera composers relish and have to take hold of. And it, I think, dictates most of the adaptational issues that come up. Tchaikovsky in Eugene Onegin made similar responses when people said, hey, you got rid of all the good things about that wonderful Pushkin poem-- all the irony, all the shadowy parts, all the ambiguities. He said, well, of course. It's an opera. They have to be different.

And they are so radically different there that anyone who loves that literary property too much is never going to like that opera. I wanted to say a little bit about the difference between what we do as composers in the theater, and what a dramatist does, because I've worked with a stage director in this project whose experience was initially as an actor on stage, and as a stage director for very many years with the Hartford stage. And he said that the biggest change for him coming into the opera theater is that composers have notated all of our pacings. And as a result, the decision making process for the director is vastly limited.

That's to say, when things happen is not in the control of the stage director. And he said one of the things that he envies is that when he was a theater director an actor would suddenly pause for a minute and a half before a line, and he would have a heart attack in the back of the theater saying, where did that come from? He's ruined my pacing. Well, if we've written just two beats rest in that spot, that's not going to happen. And beyond that, even the pace at which the line is delivered, the actual pulse of the line, since we have things like the metronome, which is the thing that gives tempo signals to a conductor, and we have all kinds of very, very refined notational procedures, the pacing of a line is under a kind of control for a musician that no other dramatist-- and this, I think, includes novelists and poets-- can control.

I've often thought about novelists as I'm reading a novel, and I'm putting it down at some arbitrary point. You know? And I may be in the middle of a chapter, and I may be planning to pick it up in five days. And I'm thinking, what a tough situation for them, because at least in my situation as a composer they may be bored, they may wish they could leave the theater, maybe sometimes they will, but under most circumstances they have to sit there for the pacing and the unfolding that I've decided. They can't put it down. I guess if they're listening on a CD at home they can, but that's not the kind of listeners I'm writing for anyway.

But in the live performance, they are there, and they are experiencing the thing more or less the way that it was planned. The hitch is, of course, that to put on an opera like the one you just heard a snatch of takes 200 people, and many of them in collaborations of tremendous significance, even right down to the people who move the things on to the stage, and those 200 people modify that precision of intent to almost as great a factor as their number. And that is sort of the contrary example to the control of pacing and the ability to keep you right there in the theater.

I want to say just in concluding a little something about text and what operatic text is. There's a very great essay by an Italian composer, Luigi Dallapiccola about operatic text in which he-- and this is actually a widely held view in the sort of Italian operatic theory world. [? Montalla ?] has written about this too. Most of the Italians agree that great poetry, intricate lyric poetry, is the worst thing for an opera text. In fact, they hold up the melodrama texts of middle Verdi as the kind of ideal operatic texts because of the plainness as of the lines, the apprehendability of the sentiment, the conciseness of the thought.

And opera is, in general, not a place where great lyric poetry comes to roost. There are reasons for that-- partly that we can't double back and re-parse a line, or try to reconstruct a line in our minds that way we can when we read a poem, or the way we can when we're in a song recital and we have a text in front of us and someone is singing a poem by Heine or some great poet, because composers do set really great poems-- sometimes against the objections of the poets-- but we do it anyway.

That's an arena where the re-thought, or the puzzling out, which I think is very important to some experience of reading their poetry, is possible. In the opera house, it's passed. And if it doesn't make its mark, if it doesn't hit, it doesn't get another chance. We move past. And we need in the opera house an immediacy of statement. If it has poetic value, it's a bonus. But the operatic texts that I love most in a literary sense are not really the ones that I love most as opera texts.

WH Auden did a very beautiful text for Stravinsky in The Rake's Progress, but I enjoy it most when I can sit with it as lyric poetry on my own time and prepare really, really for many minutes ahead, and then feel that I have a fighting chance of really absorbing what is really then a duel set of sensations-- that is, the sensation of a composer working at the highest level at the same time that a poet is working at a very high level, and it's in the theater, and it's gone by, and you can't stop it. So that the poetic medium of opera is a somewhat adapted kind, and the story has to be told, and it has to be told with regrettably very, very ruthless plainness.

I think those are the places I wanted to be. I wrote it out at home and it was only five minutes, so I think it was much better to do it in this form. And I will now sit back and turn it over to my colleagues.

HARRIS: Thank you, John.

[APPLAUSE]

Do you want to start right out?

DESAI: Being the novelist here, I get to answer the question, how do artists tell their stories at the most basic level of all. But in answering it I found I couldn't without drawing upon the other arts to an extent that surprised me. For most of my life, I've lived and I wrote in India.

And the analog of the writing life that seemed to me the most apt was Virginia Woolf's description of the writer, "I figure in an attitude of contemplation like a fisher woman sitting on the bank of a lake with her fishing rod held over its water. She was not thinking, she was not reasoning, she was not constructing a plot. She was letting her imagination down into the depths of her consciousness while she sat above holding on by a thin, but necessary, thread of reason. She was letting her imagination sweep unchecked around every nook and cranny of the world that lies submerged in our unconscious being.

Now, of course, I knew that what made me stare into the water hour upon hour in a kind of trance was the belief a writer fisher woman must have, that in that lake there lurks a fish. A sudden stubbornness is required, even a defiant stubbornness, that seems to others to border on the unreasonable. Yet these ripples are glimpses of the cruising fin, are there for everyone to see who cares to. They are what is called reality, or life, or the world, the one tenth visible section of what lies within that lake.

What sets the writer fisher woman apart is the obsession with the belief that this is only the tip of the truth, that truth is the nine tenth sections submerged below the surface. And that is the writer's prey, even the fiction writers. And writing is a way to plunge below the surface to discover and explore what lies submerged in the dark water below, then make that region a more lucid, more brilliant, more explicable reflection of the visible world and visible lives.

In this [INAUDIBLE], the writer has to cultivate the art of patience so as to make possible what Ted Hughes called the stirrings of a new poem in your mind, then the outline, the mass, and color, and clean final form of it, the unique living reality of it in the midst of general lifelessness."

Apart from patience, one requires some equipment. In all my Indian years, I believe these to consist of three items-- silence, secrecy, and cunning.

[LAUGHTER]

And I'd never heard of a writing course or a writer's workshop writing in solitude and secrecy, afraid really that the assaults of life would come too close and damage the web that I was so nervously spinning. I believed with prose that real books must be children, not of broad daylight and small talk, but of darkness and silence. With Rilke, what is needed is in the end simply this, solitude. Great inner solitude.

And with Walter de la Mare, again and again, he must stand back from the press and habit of convention. He must keep recapturing solitude. Practice this long enough, the moment comes that TS Eliot called a sudden lifting of the burden of anxiety and fear, which presses upon our daily life so steadily that we are unaware of it. Some obstruction is momentarily whisked away. The accompanying feeling is a sudden relief from an intolerable burden.

I interpret this moment as the one when one has chosen the elements of one's next work. The painter facing a blank canvas with paint brush in hand has decided where to make the first stroke, from which all the rest will follow. The composer has chosen the note from which the series of notes will rise. The writer has sensed the vision that has been courted, and now drawn the outline, its map. And the moment comes to step into it, to explore this territory that it encloses. And so one discovers rivers, valleys, mountain ranges one had not suspected.

The pen draws them on paper. Lines appear, lines made up of words. And at this stage the writer is pursued by fear, fear that one will not find the words to match it, that the words available to one have been used to the point of being worn out, that they no longer have the pristine quality required. But that is what must be achieved so that one can saw with Karl Kraus, "My language is the universal whore whom I have made into a virgin."

That was the writing life as I knew it in all my Indian years, one filled with reflection and contemplation. And when I first came to the United States and began to teach in order to earn a living, I found myself overthrowing every one of these beliefs, dragging out into the open in my writing classes what I had always hidden away with instinctive secrecy. It required a ruthless procedure of criticism, largely self-criticism, which I learned was an indispensable part of the creative act.

But it also made me feel I was doing violence to my past self. I felt as exposed and vulnerable as a turtle that's lost its shell. I feared I'd left India and my Indian self so far behind that I'd never recover them. So it was a total surprise to me when I found myself writing again, and writing, what's more, about India again. Perhaps I was trying to recover that old shelter, the old refuge, by drawing upon that familiar word again.

Here's a scene from the Indian section of my novel Fasting, Feasting. "On the veranda overlooking the garden, the drive, and the gate, they sit together on the creaking sofa swing suspended from its iron frame, dangling their legs so that the slippers on their feet hang loose. Before them a low round table is covered with a faded cloth embroidered in the center with flowers. Behind them a pedestal fan blows warm air at the backs of their necks and heads.

The clean mats, which hang from the arches of the veranda to keep out the sun and dust, are rolled up now. Pigeons sit upon the rolls, conversing tenderly, picking at ticks, fluttering, pigeon droppings splatter the stone tiles below, and feathers float torpidly through the air. The parents sit rhythmically swinging back and forth. They could be asleep, dozing. Their eyes are hooded. But sometimes they speak.

'We are having fritters for tea today. Will that be enough, or do you want sweets, as well?' 'Yes, yes, yes. There must be sweets. Must be sweets too. Tell cook. Tell cook at once.' 'Oma, Oma, Oma must still cook. Hey, Oma.' Oma comes to the door where she stands, fretting.

'Why are you shouting?' 'Go and tell cook.' 'But you just told me to do up the parcels so it's ready when Justice that son comes to take it. I'm tying it up now.' 'Oh yes, yes, yes. Make up the parcel. Must be ready, must be ready when Justice that son comes. What are we sending Arun? What are we sending him?'

'Tea. Shawl.' 'Shawl? Shawl?' 'Yes, the shawl Mama bought.' 'Mama bought? Mama bought?' Oma twists her shoulders in impatience. 'That brown shawl Mama bought for Arun and Papa.' 'Brown shawl?' 'Yes, papa, in case Arun is cold in America. Let me go and finish packing it now. It won't be ready when Justice that son comes. Then we'll have to send it by post.' 'Post? Post? No, no, no, no, very costly. Too costly. No point in that. If Justice that son is going to America, get the parcel ready for him to take. Get it ready, Oma.

First go and tell Cocoma. Tell cook fritters won't be enough. Papa wants sweets.' 'Sweets also?' 'Yes, must be sweets. Then come back and take dictation. Take down a letter for Arun. Justice that son can take it with him.' 'Now you want me to write a letter when I am busy packing a parcel for Arun?' 'Oh, oh, oh, parcel for Arun. Yes, yes, yes, make up the parcel. It must be ready. Ready for Justice that.'

Oma flounces off, her gray hair frazzled, her myopic eyes glaring behind her spectacles, muttering under her breath. The parents momentarily agitated upon their swing by the sudden invasion of ideas-- sweets, parcel, letter, sweets-- settle back to their slow rhythmic swinging. They look out upon the shimmering heat of the afternoon as if the tray with tea, with sweets, with fritters will materialize and come swimming out of it to their rescue. With increasing impatience, they swing and swing."

[APPLAUSE]

But while writing down a scene which is so well known to me that it's imprinted on my skin and my eyes, there are also these scenes from my new American life pressing in on me, demanding my attention, demanding to be addressed, if only from the point of view of a stranger and a foreigner. So I read a scene from the second American section of the book Fasting, Feasting, which follows Arun in his trials.

"It is summer. Arun makes his way slowly through the abandoned green of edge hill as if he were moving cautiously through mast waves of water under which unknown objects lurked. Greenness hangs, drips, and sways from every branch and twig in front in the surging luxuriance of July. In such profusion, the houses seem lost, stranded, as they might have been when this was primeval forest. White clapboard is the most prominent, but there are houses painted dark with red oxide, some with the military gray with white trim.

These touches of color seem both brave and forlorn, picture book dreams, pitted against the wilderness without conviction. Outside many of them the starred and striped American flag flies on a boast with all the bravado for a new frontier. In direct contradiction, there are the more domestic signs of habitation that imply settlement by generations-- rubber paddling balls left outside, go karts and skateboards, garden furniture and garden statuary, pink plastic flamingos, boys beside the birdbath, spotted deers or hatted gnomes crouched amongst the rhododendrons like decoys set out by homesteaders conveying some message to the threatening hinterland.

Arun keeps his chin lowered, as nervous as someone venturing alone across the border, his eyes glancing from side to side into the windows. None of them are curtained, many are large. He can look directly at the kitchen sinks, the pots of flowering busy Lizzies, the lamps, the dangling glass decorations. There are so many objects, so rarely any people.

Tucking his chin into his collar, he ponders these omens and indicators. He turns into Barbary Lane and walks past more trimmed lawns, down the slope to the last house on the hill. Here too, a red and white blue flag flies upon its poll, its rope slack in the summer stillness, the mailbox holding its measure of junk mail too voluminous to merit collection. Here too the big picture windows are lit, the rooms empty like stage sets before the play begins. Is there or is there not to be a play?

He walks around to the side of the house and sees Mrs. Patton is there. She is unpacking several large brown paper grocery bags, placing cartons and containers on the counter, slowly, thoughtfully putting away each item after several minutes of holding and considering it. Arun stands watching her purse her lips and occasionally touch her mouth with a plump, freckled hand as she bends to put away the cat food or open the refrigerator and stack frozen cans into its icily illuminated spaces.

Now she stops, a can of plum tomatoes in her hand and doesn't know what to do next. She's frozen with a stricken look on her face, like an actress who's forgotten her lines. Although, at the very heart of this domestic scene she seems lost."

Well, you'll agree that these are two very disparate fragments of experience. And looking at them, I realize my world had really been shattered into bits. Now I had to go down on my knees and sort out the fragments, put them together again, but in a new design, since they didn't belong to each other. They belong to different worlds.

But hadn't Elliot taught me that the writer's mind is a receptacle for seeing and storing up numberless feelings, phrases, images which remain there until all the particles can unite to form a new compound. And to satisfy that need to unite, I sifted through the material to find the motifs that ran through them. And in the final scene of the book, I draw them all together again.

"It's the end of the summer. Arun has packed his belongings into the blue leatherite suitcase he's brought with him. He's puzzling over what to do with the parcel that's arrived from India only this morning with its innumerable wrappings of brown paper and string, each bearing the mark of his sister's clumsy and impatient care, providentially catching him at the Pattons' before he moves out and back to the campus. The parcel contains a package of tea and a brown wool shawl, both calculated to help him through the coming winter.

What hadn't been calculated that he hasn't the extra space for them in the suitcase. He picks up the box of tea in one hand, the folded shawl in the other. One is heavy, the other light. One's hard, the other soft. A lopsided gift. He holds them, trying to find the balance.

He goes downstairs to find Mrs. Patton, the tea in one hand, the shawl in the other. Mrs. Patton no longer lies in the yard sunbathing. The days are warm and still with a silvery sheen. But she seems to have taken an aversion to the light, even to the outdoors. She no longer spends much time in the kitchen either. She has stopped offering to take Arun shopping, although the kitchen is drastically depleted, only remains left at the bottoms of jars and bottles.

She dresses now in skirts and long sleeve blouses. She has voiced a tentative interest in traditional medicine. She talks of taking a course at the leisure activity center in yoga or astrology. There, catalogs pamphlets and leaflets lie in drifts around her now as she sits on the porch quite still on an upright chair.

She's holding an acupuncture chart on her lap, but is staring over the top of it through the wire screen at the yard, which is empty except for the cat carefully stalking a moth in a bed of dead and wilted flowers. Everything in that scene looks fatigued, or spent, or faded. Arun goes quietly up to her-- too quietly, because she gives a start and clutches her neck in fright.

'I'm sorry,' Arun apologizes, clearing a frog in his throat. 'I have brought you some presents. I'm leaving now, Mrs. Patton.' 'Leaving now?' she repeats, bewildered. 'The semester starts tomorrow,' he reminds her. 'I've got to go back to the dorm. I'm packed.' 'Oh dear,' she says mildly. 'Please take these things. My parents sent them for you,' he lies, hoping they'll never guess what happened to their gifts, and hands her the box of tea, which she takes with a polite murmur of surprise and turns over when her hands, studying the label with the habitual attention that she gives to consumer products.

And she queries hopefully, 'Is it herbal?' Arun wrote opens out the brown shawl. She shakes out the folds, arranges it carefully about her shoulders. An aroma arises from it of another land-- muddy, grassy, smoky, ashen. It swamps him like a river or a like a fire.

She looks at him, then at the wool stuff on her shoulders in incomprehension. She picks out a fold of it and sniffs, and slowly her face spreads into a flash of wonder. 'Why, Arun,' she stammers, 'This is beautiful. Thank you,' she repeats, 'Thank you,' and puts her hand to her neck to hold the ends of the shawl together.

He withdraws quietly, going up to collect his suitcase, then finding his way but out by the kitchen door, leaving her sitting on the porch with the box of tea on her knees and the shawl around her shoulders."

Well, with that, the book was done. And I was left saying, as I always do, oh no, that's not what I meant.

[LAUGHTER]

And so you begin spinning the next one.

[APPLAUSE]

GLUCK: It's much nicer to listen. It seems very odd to be here. I feel as though I have never in my life told a story, except the most rudimentary and repeating human stories-- birth, love, loss, death, rebirth. I would have thought that what would preoccupy a poet would be the world of sensation. But this isn't true either.

I think that what tends to interest me is dilemma, the investigation of dilemma, or psychological predicament of some kind. And the danger, of course, is that the work by virtue of its obsessive nature and rudimentary quality, would be repetitious. The task of the artist is to keep the obsessions from being boring, first to the artist.

[LAUGHTER]

I do this because it's thrilling. I mean, I'm mostly not doing it. But when I am doing it, it's very exciting. And it's exciting because of a sensation of novelty and exploration. What I like is the sense that I have heard a new tone, and it will take me on a voyage. And I have no idea where. You begin with that tone.

The best analogy I can make-- and obviously it's imagined, because I can't reconstruct the experience of the infant in the cradle-- but it seems to me likely that a small child listening to conversations in the next room before knowing language will be able to infer from the rhythms, the rising and falling of the parents' voices, some meaning. And the task of the infant is to discover the meaning of the words that fill the meaning of the rhythms.

The task of the poet is the same. You hear a rhythmic structure, or a line, a phrase is visited on you. It's nonsense usually. It's a particle. It's a fragment. But you sense its resonances, and it torments you until you can find for that line the context that will allow it to speak.

I thought what I would do-- Ellen said we were to have fun. I thought, we'll just chat here sort of like Plato. But--

[LAUGHTER]

--I see we can't quite do that. So I'll read three poems from very different periods of my life that are thematically identical, and, I think, in manner very different. I can point out even in the first and earliest a strategy on which I came to depend. A problem is that if you're not telling stories, how can you achieve a sense on the page of drama? And I think you can do so by changing course in the middle of the journey, by calling into question the premise on which the poem begins, by arguing within it so that essentially you have a multiplicity of voices speaking.

Certain forms of irresolution, not leaving things out, which always-- well, I don't do that-- but by setting in motion a world of questions and ideas that cannot simply be resolved. I'm obliged because of this situation to read these poems to you. I make a lot of my living doing poetry readings, and I have never liked the form. First of all, I don't like the way my voice necessarily substitutes for the voice that I hear on the page.

People will come up after a reading and say, oh, now I know how you mean the poem to sound. And I say, no you don't. You will only know it if you read it. And oftentimes there's a terrible discrepancy between the palette of which my instrument is capable and what seems to me the sound I have heard. And sometimes when you read work for the first time and are struck by that, you're grief stricken at the inappropriateness of the sound that came out of your mouth.

In any case, I dislike reading principally because it turns a poem into a relentlessly sequential experience, each line erased by the line that follows it. This is not what happens when you read it on the page. It's small enough so that it can be held in the mind, and its resonances and echoes registered so that the moment of reading contains that-- invents [? a ?] net.

The first poem I'll read was written when I was about 20. It's called "Cottonmouth Country." And it was a piece of my now almost entirely repudiated first book. I try to cultivate toward this book a kind of tenderness, but that's the best that I can do. But there are poems in it of which I'm still proud. I would hardly read this otherwise.

"Cottonmouth Country." "Fish bones walk the waves off Hatteras, and there were other signs that death wooed us by water, wooed us by land. Among the pines an uncurled cottonmouth that rolled on moss reared in the polluted air. Birth, not death, is the hard loss. I know. I also left a skin there."

None of this happened as fact. I passed through Cape Hatteras. I thought, what a beautiful sound that word is. I did see a snake. But the poem came from some other nest of memories and ideas, and the preoccupations I began by talking about, this is a fairly rudimentary and recurring human experience, the experience of being forced to be born again, to change. That would be the other word for it. That's the word most people use.

The next poem that treats of those same themes was written many, many, many years later, and tonally utterly different. And yet it's the same experience. This is from a book called The Wild Iris, 1991, I think, the poem was written. The first poem was late '60s, '70s early.

This is the title poem of the book. And the opening lines were the lines with which this book began. I hadn't written a word for two years. That's not, for me, uncommon, and increasingly I find that I write in kind of seizures, which sounds exciting. It sounds like possession. It sounds like the visitation of the muse.

But in fact, it's very complicated, because there's no feeling of agency so that when you finish you have no sense that you've actually written the work. This is not to say that you think the muse wrote it. What it is to say is that you fear you have stolen it, that you have remembered it, that it's somebody else's and you've appropriated it. So you start sending these poems that were written suddenly three, four a day to your friends, asking if they recognize any of their lines.

But you can't send them to everybody in the world. And it's rather frightening. And I find having now written three books like this, I feel a wish to be, again, the studious, the endeavoring maker. Of course, I'm sure that my nostalgia for that form has not sufficient memory of the ordeals of that form.

Anyway, this is a book that was written very quickly. But the first lines of this poem I had in my head for two years. But I didn't know what they meant, and I didn't know who said them, in reference to what. This was not the first poem of the book written, but after I had written a cluster of these flower poems I thought, this is where those words come from. This is who speaks them.

This book is organized as three kinds of voices-- a human voice-- the poems spoken by the human voice are called either vespers or matins-- voices of the earth-- the poems that represent such voices bear flower names-- and whatever is not included in those other two, whatever name you want to give it, the celestial. The not human.

"The Wild Iris." "At the end of my suffering, there was a door. Hear me out. That which you call death, I remember. Overhead noises, branches of the pines shifting, then nothing. The weak sun flickered over the dry surface. It is terrible to survive as consciousness buried in the dark earth.

Then it was over. That which you fear, being a soul and unable to speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth bending a little, and what I took to be birds darting in low shrubs. You who do not remember passage from the other world, I tell you I could speak again. Whatever returns from oblivion returns to find a voice. From the center of my life came a great fountain, deep blue shadows on azure sea water."

Well. I was grateful to be writing again, and that's what that's about. But like "Cottonmouth Country," it's a poem about an immense transition, the transition from silence to speech, from drifting, buried unconscious to conscious speaking. In "Cottonmouth Country" its birth, not death, is the hard loss.

The last poem I'll read of this type, though I could probably read 50, is the last poem in my most recent book. I have a new one coming out in April. And the poem is anomalous within the book. It was the first one written, and when I wrote it I thought, oh damn, I can't write anymore. I can only write these insouciant Mary little poems.

In the book, it works a different way. But you will hear it without the book, and so it will be an insouciant Mary little poem about rebirth that begins-- this one is much more grounded in social experience, experience of divorce and relocation. And the book uses a lot of local footage. It's a very Cambridge book.

"Vita Nova." "In the splitting up dream, we were fighting over who would keep the dog, Blizzard. You tell me what that name means. He was a cross between something big and fluffy and a dachshund. Does this have to be the male and female genitalia?

Poor Blizzard, why was he a dog? He barely touched the hummus in his dog food dish. Then there was something else, a sound like gravel being moved, or sand, the sands of time. Then it was Erica with her maracas like the sands of time personified. Who will explain this to the dog?

Blizzard, daddy needs you. Daddy's heart is empty, not because he's leaving mommy, but because the kind of love he wants, mommy doesn't have. Mommy's too ironic. Mommy wouldn't do the rumba in the driveway. Or is this wrong, supposing I'm the dog, as in my child self, inconsolable because completely pre-verbal with anorexia.

Oh Blizzard, be a brave dog. This is all material. You'll wake up in a different world. You will eat again. You will grow up into a poet. Life is very weird, no matter how it ends, very filled with dreams. Never will I forget your face, your frantic human eyes swollen with tears. I thought my life was over, and my heart was broken. Then I moved to Cambridge."

[LAUGHTER]

[APPLAUSE]

I'll stop.

[APPLAUSE]

HARRIS: We are now open for questions. And there are microphones on both sides, so if you--

GLUCK: You can use the podium.

HARRIS: Yes, you can also go over here. We have disdained it, but you are welcome to it.

AUDIENCE: This is a question for John Harbison. I wonder if you could articulate how you approach writing music that has no extra musical elements, that's pure music.

HARBISON: Exactly the way I work when I'm with words or with theatrical action. That is, what sets it in motion for me is what I would call a musical thought. So it's not a gear shift. Of course, my view of opera, and in fact song composition, is that they are first of all pieces of music. And then they have to do with other things. And in that view I find myself somewhat out of phase at least with some elements of the opera community who evaluate opera more on the basis of the libretto, or perhaps even of the sequence of events.

But for me, music is a little bit as described by Anita and Louise, it's a fragment that you're haunted by, and you have to find someday a place for it. And if you're writing a big piece of, say, theatrical music, you have someplace that you store those things until they start to make sense. But they make sense, I think, first as a musical train of thought, as I said, that you then hope can be applicable to a dramatic action.

GLUCK: May I ask a question?

HARRIS: Yes, please.

GLUCK: I have to. I'm curious, John, to know what draws you to a text, because to embark on an opera is to invest an enormous amount of time in a project. You can't, I suppose, hear a cluster of notes and think, Gatsby. Or what happens?

HARBISON: No, it really is that.

GLUCK: Is it like that?

HARBISON: Yeah, because it's very greedy in the sense that in any setting or anything dealing with a text is because I'm getting the gift of some musical associations. And the working out of a libretto for Gatsby was just hear the sections I can find music for. And what dropped out was what I didn't have music for. And really that's a bit of the same with setting a song to a poem. If the music seems to be coming along, and very often the poem as a vehicle to write a piece of music that I wanted to write, and that can then work together with the poem, can be a little more intelligible with the help of a poem.

But it really isn't a sense of, this will be a good opera, or this will be a good poem to set to music. It's more that you can't get rid of a kind of an association between some music and some substance that is not notes.

AUDIENCE: My question is a distant echo of the previous session namely about language in writing, in creative writing. And I have a question that is two parts, which I would like to illustrate that we thought were trivial or meaningless. Maybe trivial and meaningless anyway, but one part has to do with style versus content, and to add to writing in one's native language versus just not.

To illustrate the first, if you look at the writing of Addison, of Tatler and [? Steele, ?] which Dr. Johnson, according to Boswell, recommended as one of the best English styles, is stories of Roger de Coverley and not very great depths, as for example, Emmanuel Kant. But Kant writes in a style which is very, very difficult to read and not very appealing, even if he has important things to say.

So does Paul of Tarsus, better known as Saint Paul, except some parts of Epistle to Corinthians, people tell me his Greek is atrocious. His first two languages-- transition to the second question. Second part, his two languages are Hebrew and Aramaic, so he doesn't know Greek. But his impact as creator of Christianity was tremendous.

Let me move to the second part, namely native versus not native language. And there are people who write excellently in a language was was not their first language, like Isaiah Berlin who was born in Riga in Russian, or Eva Hoffmann who was from this university. But they're essayists, not creative writers. Creative writers, I can think only of Conrad and Nabakov who wrote good English. Now in Nabokov, at the end of Lolita, postscript says, in spite of one's success, maybe it was tongue in cheek, his English was not what the Russian language would do for him.

Now Conrad, I don't know. Obviously he learned English somewhat in his childhood, but it was not his first language. And finally, a question-- the first one was really to Louise Gluck, part the question of the pre-verbal level if the language is your childhood language. The second part is the foreign writers. I think the Indian writer is a special case, because many of them, for example, A Suitable Boy, are reading bilingual, so it's English maybe not their second language. To repeat, to sum it up, the question of first language versus second, and style versus content, and importance of style irrespective of what the content is.

HARRIS: Who would like to start?

GLUCK: I don't know how to start. So I don't quite know what's being asked.

AUDIENCE: The question is how important is style--

HARRIS: Do you see a difference between style and content? Do you see a distinction between style and content?

GLUCK: I suppose if you're studying a piece of work and writing an essay about it you can isolate its content. But its content is put on the page with a certain choice of words that determines the way that content is understood. Content is tone, the tone toward the material. I don't know where that fissure between them lies confidently enough to elaborate it.

HARRIS: I mean, our questioner is posing the idea, as I understood it, of works that are very good in style, even models of good style, where the content is superficial at best.

AUDIENCE: [INAUDIBLE]

HARRIS: Yes. Yes. And then the opposite.

GLUCK: Well, I think if there's glorious style and spiritual deficit, it won't be memorable.

AUDIENCE: How about native versus second languages?

GLUCK: That's Anita.

HARRIS: I think Anita.

DESAI: That's my turn. I don't know. I think one writes the language one reads. And there's this whole world of literature for us to dip into. And what writers do, what artists do, is constantly amalgamate, put together. What I would love to do is make a language up of all the languages I hear and know, use whatever fragments come to my mind at any given moment, and make up this patchwork which I live with.

I know it wouldn't have any meaning for my readers. I can't do that. But that's what I tried to move towards. Maybe I can only use tones and rhythms to differentiate the languages. But the idea is one of inclusion, not of exclusion.

HARRIS: That seems to fit in so well with the previous panel. Another question.

AUDIENCE: I have a comment for John Harbison about your point that the singing somehow took away from the negative connotations of the bootlegger gangster and Gatsby. And I was left to think about whether singing and opera is all that special. For example, you want to take a monster like Iago. And it's not just that he sings, but that he's originally conceived in Shakespearean poetry, which immediately gives him a very different quality.

And then if you transfer that back to Gatsby, the Gatsby we know speaks Fitzgerald poetry. No gangster ever said, her voice was full of money, or it was just personal, or any of those wonderful lines of Gatsbys. He's saved from his gangsterhood in a sense by the art of Fitzgerald.

And this raises the whole larger question that I used when I taught literature and students wanted to talk about the possibility of a truly pessimistic or nihilistic work, and that it's almost impossible to have such a work of art, because the triumph of the art is an affirmation that negates a true negative view of life. You really can't have a great work of art that doesn't save itself by virtue of the artist's achievement of form and closure from negativism. And so I wonder whether opera is all that different when just for the fact that you sing Gatsby's voice, he's already conceived in a poetic fashion.

HARBISON: I guess that's a question of how we perceive it. Opera composers tend to work very pragmatically, I think, to the advantage of what they're doing. And in the case of Iago, people have fought for years about whether Boito transgressed against Shakespeare by introducing Iago with his so-called credo, which is a very Italianate and extremely loose [? presi ?] of some of the issues that he brings up in the Shakespeare play, but couched in, to my mind, such an incredibly overt, dynamized form that anyone who is concerned, say, about the transfer ought to be by that time kind of uneasy about how much has to change, I think, to deal with the difference of the medium.

I think once you hold a note for a couple of seconds, you have absolutely crucially changed the nature of the medium of expression. And opera is, if anything, about people holding syllables, emphasizing them, putting the number of syllables on a given note, all the things that to me are the transformative qualities of singing as opposed to speech. And thus, an art of a very different nature.

I wasn't really dealing with content, or whether the nature of the poetry couldn't be in some way preserved, or whether a pessimistic work could be written in one or another medium. I was really dealing with just the physical production of sound.

AUDIENCE: Well, you introduced it as an answer to someone who said, how could you make an offer out of such undeserving unfit people. It wasn't the remark that there wasn't anyone in the novel [INAUDIBLE]

HARBISON: No. And I think my response to that, which was somewhat facetious but also quite serious, was that once the inevitable distortions and expressive heightenings take place, these characters are automatically not the characters we knew and perhaps loved, or however we react to them in the novel. They've taken on a completely different mode of communication with their audience. And thus, anyone who is looking for parallels is going to be disappointed-- exact parallels.

HARRIS: Another question? Who has the mic? Here we have-- oh, sorry, Irving's second if you can. All right?

AUDIENCE: I'm sorry, what?

HARRIS: We have someone in the back first.

AUDIENCE: Go ahead.

HARRIS: Okay.

AUDIENCE: Okay, the title "Vita Nova" reminds me [INAUDIBLE] And so my question is, is there an evolution which are the major step in which the way ancient poets spoke about human nature evolving to more than there is a way to speak about it?

GLUCK: Well, this is Latin. It's not Italian, and though obviously it calls up Dante, and there are little Dante resonances in the book, the phrase existed before he made it so well-known. Is your question has there been an evolution in human feeling?

AUDIENCE: No, I mean, we are speaking about the way in which people tell stories. So is there an evolution from the past to know in the way people actually tell stories?

GLUCK: Well, there are shifts in what the taste of a particular time fancies, obviously. And there is a sense that certain ground has been covered by great masters, which were you to advance upon it would involve your writing a work that's going to be held up beside theirs. I don't think that you should necessarily refuse to do this, but I think you have to be alert to the fact that that comparison will be made.

I think that as historical conditions change, and our concerns change, and the mode of being human changes, I mean, just that. The idea of the celestial now, of the divine, is very different. We are not commonly a people capable of the kind of automatic faith that was a condition of life centuries ago. This is a change. But it means that the great subjects, we're all still going to die. They are still our subjects. I don't know how else to answer you.

AUDIENCE: I want to make some comments that underline some of the things that John was saying in relationship to one thing in particular that Miss Gluck said, that presenting your poems by reading is very different from an ordinary person reading the poems on the page. And I was very much impressed with your reasoning, which was that the poems on the page have a resonance that arise from the fact that somebody is reading and getting into the mood of the rhythm. And I think that is very significant in terms of what John was saying, also, that in our ordinary thinking we lump too much together.

In fact, the question asked by this panel, what is it that poets do? Or what is it that how people narrate? But in a sense, the poets and the composers aren't doing it. It's the art form. The art form of a poem on a page is very different from the art form of a poetic reading, which is already theatrical.

The art form of poetry or literature is very different from an operatic use of it. So we talk about setting Shakespeare to music, but Shakespeare is not set to music. He's simply a goad or an opportunity that the composer has to use in any way that is appropriate to his very different kind of art form. And Iago is a good example, because Verdi's Iago is very, very different from Shakespeare's Iago and has to be evaluated in terms of the capacity of operatic music as opposed to the capacity of a theatrical performance.

So that in a sense what one should be asking would be the opposite kind of question, how is it that these great varieties of communications, of feeling, emotion, ideas, occurs through the different kinds of art forms, each of which have their own techniques, their own access to a relevant meeting which is based upon that technique, which has to show itself through the technique, and can communicate with audiences who are sufficiently schooled to be able to appreciate what is possible in whatever medium is being used by the artist, or whatever medium has taken over the artist instead of starting the other way around as if artists are independent of their medium.

HARRIS: Yeah. We need to take a shot at this.

AUDIENCE: I'm sorry I asked such a smart question.

HARRIS: Is there anything anyone would like to respond to this? I'm not sure it's a question.

AUDIENCE: No, I said it was a comment.

HARRIS: All right, maybe we can move on.

AUDIENCE: But it's a comment that can be questioned.

HARRIS: It can be questioned. Yes. Yes. Do you want to pass the microphone down? And is there another microphone out here somewhere?

AUDIENCE: [INAUDIBLE] Can you hear me?

HARRIS: Let's pass this up to you when we finish here. All right?

AUDIENCE: Some artists exist just as independent entities, and some exist within universities as you all do. I'm just interested in how being educators has affected your work as artists, if at all. Short question.

DESAI: Speaking for myself, because I mentioned working with students and writers, workshops and groups, I can say that it forces one to be much more analytical. I think one is critical in the act of writing, composing, whatever, that critical faculty is always alert and watching over one's shoulder, what one is doing. But I think artists very often fear to analyze, certainly in the process of creating a piece of work. I think analysis for us always follows, it never precedes.

And when you go into a classroom, you find the order of things sometimes reversed. And it's something very difficult to get used to, actually.

GLUCK: I love it. I love to teach. And I feared beginning to teach, because I was afraid that my enviousness of talent, if I were exposed to it in a period when I wasn't writing, would be such that I would give bad advice.

[LAUGHTER]

But that turned out not to be true. What I discovered, amazingly, was that actually I think I analyze all the time. It's why I hardly ever leave my house. But I think that I discovered that when I wasn't working, the pieces of my mind that needed to be used in my own work were being used. They were being fueled by the attempt to articulate what about a student poem, which was still malleable, kept it from being memorable.

Why was it not a memorable work, and could one say where and for what reason it faltered, and then since the act of diagnosis is actually pretty simple, could one suggest alternative strategies that would transform this still shifting work into something stable and resonant? And I began to teach when I was about 28, and I count on it. I mean, there are times when I think I cannot commute one more time.

But I like being in a classroom. I like looking at poems my students have written and figuring them out. And I like being obliged when I teach literature to prepare myself for the questions of a student body that's quite brilliant. It's terrifying, but I like it. I need it. I need an external structure of obligation.

HARRIS: John, did you want to speak to this?

HARBISON: Well, since in music we deal with a kind of different audience from the lyric poetry audience and the people who read novels, that is to say they're in the room responding, buying tickets, and applauding or not, one of the things that teaching has focused for me, it sort of narrows down a lot of what I think about in all the teaching that I do, that in music we have the task of trying to get less experienced musicians to balance between what I would think of as their inner ear and their outer ear. That is, the inner ear that conceives interesting adventurous things, perhaps structurally ambitious things, and the outer ear that deals with how it goes out and how it's received way far in the back rows, and how it registers to other people.

And in recent times, I think because we are an art that exists, though it's a small public relative [INAUDIBLE], it's a real public-- we exist in a commercial world-- the outer ear has begun to be very overemphasized, I think. And what I try to do now as a teacher is to emphasize the other side to a great degree, that is that the art, if it's to continue to develop, needs to still reside in the speculative as well as the commercial. And I know Anita has to sell, or perhaps doesn't have to, but may be willing to sell a lot of copies of her books. But she doesn't actually have to go on stage with them, or coach people how to interpret them, or in fact persuade people to speak them correctly.

And part of what we train musicians to do is all of those things. And it's just helped me to define a relationship to that practical world, which I think is very valuable.

HARRIS: [INAUDIBLE] question.

AUDIENCE: My question is somewhat related, because as I heard at least one or two of you mention--

HARRIS: Turn the microphone toward you. [INAUDIBLE]

AUDIENCE: I heard at least one or two of you mention truth in describing your telling of stories. And so I'm wondering whether your role here in pursuing your aesthetic inquiry, if that's what you would call it, in an institution full of scientific inquiry, whether you have broadened and whether your understanding of scientific inquiry has been enriched by your aesthetic inquiry, and vice versa, whether you can help us perhaps with more understanding of the relationship between your kinds of search for truth and the scientists' or the mathematicians' search for truth.

DESAI: Well, I write fiction which sounds the furthest of all from truth, but it seems to me that when you're writing fiction it really frees you in your exploration of truth. One doesn't need to adhere to any particular category, restrict oneself. One is free in one's exploration. But that is what one is searching, certainly, to represent.

HARBISON: I just respond on a very practical or a level about teaching at this institution. We get a kind of volunteer personality in the arts, someone who accepts the idea that you have to do a lot of work to make something, and that's kind of an Institute wide assumption, which I feel we benefit from. There is a story of Anita's, it's called The Artist's Life that I like a lot, because it has a young painter who gets fired up in a kind of class about painting, and then discovers it's actually almost nicer and easier to just live like an artist but not do any more paintings.

[LAUGHTER]

And that's kind of the person I've taught in some other locations. But it's rarely the kind of person we get here, because it really is a place where the atmosphere is you make things, and you have to do a lot of work.

HARRIS: Here we have another question?

AUDIENCE: You were talking about how in opera, especially, it's such a collaboration. Do you feel like all those collaborators are contributing to the story you're telling, or are they getting in the way, especially because we're such a visual society, and the designers, and the directors, and the actors themselves who are singing, and yet they're presenting a visual picture, and they think that they themselves are contributing to the story. Does that destroy what you're doing? Does it corrupt what you're doing? Or do you feel like they are helping you to tell the story that you're doing with the music?

HARBISON: Opera's a very strange world, and a gigantic machine. And I'll just mention two of the people that I've developed the most respect for-- the prompter--

[LAUGHTER]

--and the stage manager who calls all the signals for all the people who are trying to make the stage change in time for the next scene to go on. And those are things that we don't see when we're there, but if those people are not phenomenally good, you don't have an evening. I think that's one of the fascinating things about the theater, and it's one of the things that makes it very accident prone and dangerous, as well.

AUDIENCE: I've had this vision of the artists perhaps typified by a sculptor who stands in front of a piece of marble and envisions the whole and then slowly chisels his way into the final form where he can deal with detail. And yet, I heard each of you, I think, refer to what I would consider an opposite approach of starting with fragments, and putting together fragments, and finding a context for fragments, so building up from fragments and details to a larger vision rather than starting with a vision and chiseling your way down to the details. I'm wondering, is there an analogy, or [INAUDIBLE]

GLUCK: Actually, I think that there is. I mean, it feels very familiar, that description of the sculptor. I think what he's doing first, staring at that piece of stone, is waiting for the stone to speak to him. And certain pieces of stone remain obstinately still. They just stay large chunks of marble. And in others, in the grain, in something about the alteration within the color, he sees the beginning of a gesture, the gesture of a chisel.

And then once that has been affected, he and the stone are in dialogue. That seems sort of familiar, even though I have nothing to point to in my medium that says block of marble. But it feels like there's a world and you have to give it form the way you would look at the stone and say there is something in it, resident within it, but I can't say what it is yet.

HARRIS: Anita or John, you want to talk to fragments?

DESAI: Your question made me think of that great Rodin sculpture, of course, in which he seizes the figure out of this unfinished piece of marble, really. Rodin wouldn't finish the sculpture completely. He would always leave a piece the way it was to show you how to create a work of art. It's a dance with your material, also a battle with your material. But you are locked together with it.

HARRIS: A question in the back.

AUDIENCE: Mr. Harbison, did you write your own libretto?

HARBISON: Yes.

AUDIENCE: Which came first, and how did how did the process take place?

HARBISON: I had a lot of music before I wrote the libretto, and I fitted the libretto to the music that I had. But that's just my method. And obviously I had to have a complete libretto before it was going into end of the piece, and the mistakes I made with the libretto created the most intractable problems with the piece.

AUDIENCE: If a colleague of yours in the physical or social sciences arrived in your office and said, I'm writing a grant to understand the scientific basis of this thing that you artists call the muse, what advice would you give that person?

[LAUGHTER]

HARRIS: Yes. Would you like to respond? I'm sorry. I shouldn't [INAUDIBLE]. I apologize. I'm very sorry. The panel is stumped.

HARBISON: We're stumped.

DESAI: Stumped.

HARRIS: They're stumped. All right. I think we'll take one more question.

AUDIENCE: Each of you has expressed some criticism of your own works in terms of things that weren't satisfying about them. How do you decide when a work is done, versus it needs revision, or you just want to throw it out and start something brand new?

[LAUGHTER]

DESAI: Want me to? Well, I write novels and those take a lot of time. They take years to write. And I think, finally, I admit that I have run out of energy, that whatever energy I had to put into this work is at an end now. It's disappeared. And then the book's at an end. That's the dissatisfaction. I can't do anything more. I would like to, but I can't.

HARBISON: A similar sensation, she said that she got to the end of that novel that she was reading from, and it was not quite what she thought it was going to be. That's not always a bad feeling. You get to the end of something and it's not what you even were shooting for, but it's something else. And I think you get to a point where you accept that. And in my case, I am always very anxious to go on, whether it's a run out of energy, or just an impatience, I don't know. But it does seem that there is a point at which you do want to go. And in the opera world, that's still a point where people are telling you you should be making changes.

GLUCK: I don't know that I can add anything to what has been said on this point.

HARRIS: Do you know when you get to the end of a poem?

GLUCK: A poem? Well, I've been mainly writing now constellations so that the books are really supposed to be taken as entities. Yeah, very clearly I know when I'm at the end. A voice is spent, or an idea is depleted. And then there may be a lot of work still to do, which I embark on, but I know-- and sometimes I'm wrong, actually. I have made mistakes and realized that something else had to be added.

But you realize that in various ways. You realize it as you attempt to order the material, and that the form that you had in mind is not going to work with this particular set of mosaic pieces. But yeah, it's depleted. It's finished. You've done what you can do with this-- seems like a range of notes to me. I mean, that may sound awful to you, but that's what it seems like.