36th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration at MIT - Gerry Hudson

[MUSIC PLAYING]

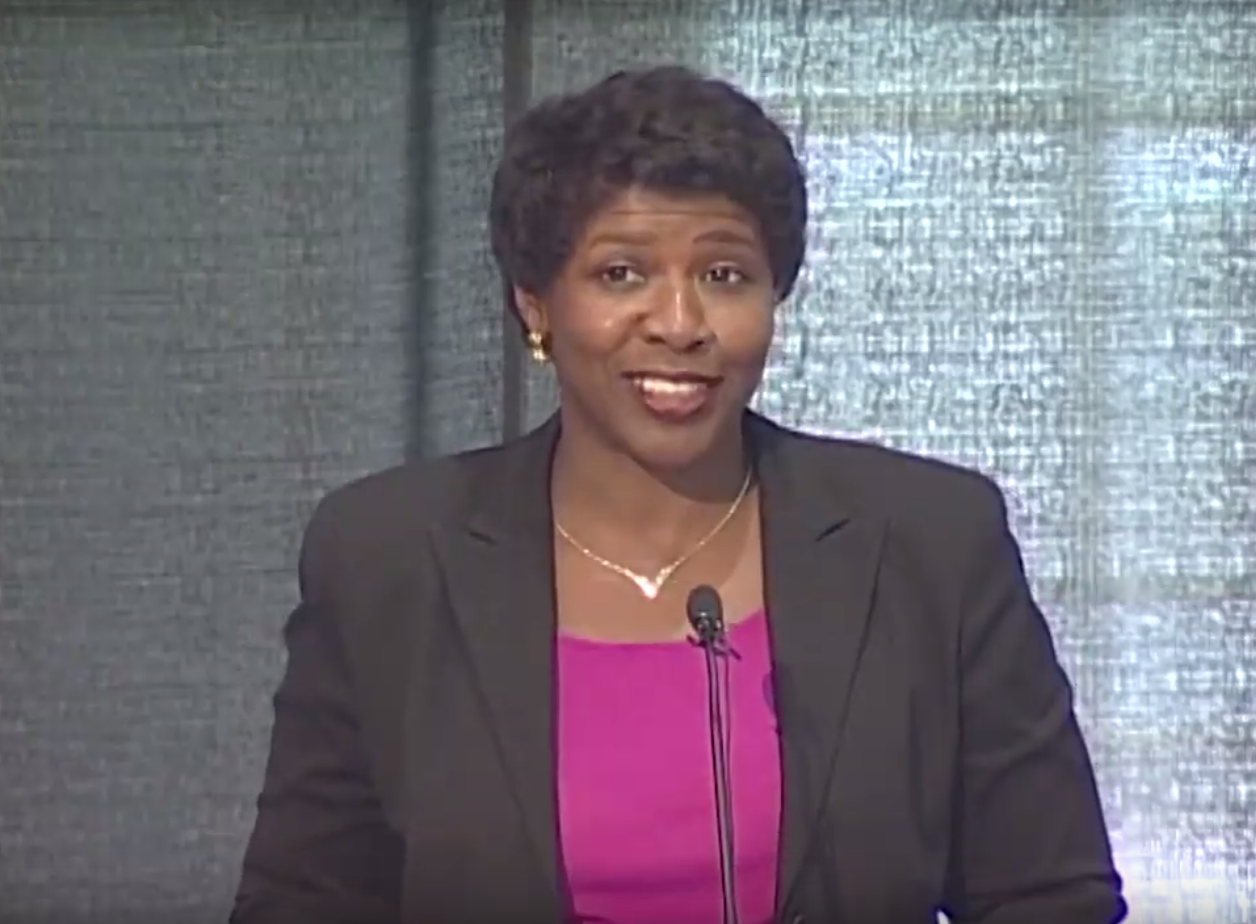

PRESENTER: And now it gives me great pleasure to welcome the 16th president of MIT, Dr. Susan Hockfield. She will give some remarks and proceed to introduce our keynote speaker, Gerry Hudson. President Hockfield.

[APPLAUSE]

HOCKFIELD: Thank you, [INAUDIBLE]. It's-- good morning. What can I do to follow this amazing, amazing program? I would say, there is no better way-- I can't imagine a better way to greet the new day than soaring on the wings of the MIT Gospel Choir. And [? Jermaine, ?] thank you very much for waking us all up to the day and its great potential.

I also want to thank Dylan and [? Zenzi. ?] I am so proud of both of you. Dylan, you really called out to all of us. It seems to me, almost every week that I'm at MIT, our motto, mens et manus, means more and more. But you really called out for us how theory is great, but alone, it is just insufficient until it's reduced to practice. And it really sits at the heart of MIT, and not every place. Not every institution of higher education.

And [? Zenzi, ?] your exaltation for us to not only be thankful for our gifts, but to use them with a sense of really joyful responsibility, it's just so wonderful. What a great call to action. We are incredibly blessed to have the two of you, with your intellect and insight and joy, to be part of this community. So thank you very, very much. Actually, would you join me in thanking them?

[APPLAUSE]

I also want to thank our hosts this morning, the Committee on Race and Diversity. This breakfast is only part of the work that they do on campus-- frankly, all the time, every week, every month-- to be sure that these issues of race and diversity stay in the front of our focus, and keep our minds on the work that yet remains to be done to make this campus the place that we know it can be.

On the annual calendar, this annual celebration of the legacy of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is an important moment. It's annually an important moment for coming together for finding fresh inspiration, which we receive in bucketloads every year at this breakfast. It's great to be here again.

But on that reflection about sources of inspiration, I have to comment for a second on the dedication of this morning's breakfast to Leo Osgood. I want to take a moment to acknowledge that, with his passing last November, MIT really lost one of our most important and enduring sources of inspiration. Over nearly his three decades at the Institute, Leo Osgood made innumerable contributions as a professor, as a coach, as the dean on call for what was then called the Office of the Dean for Student Affairs, as a friend, as a mentor, as a counselor, and certainly as a comfort to generations of students.

Among his many contributions-- and I'd say this is just a very small list of a much, much longer list-- let me just call out his leadership in conceiving and initiating the Martin Luther King, Jr. Visiting Scholars Program. And we celebrated the visitors this year. Welcome to MIT. Glad to have you on campus. His seminal contributions to Project Interphase that has benefited so many students at MIT. His work as co-chair of a presidential task force on the career development of underrepresented minority administrators, something we continue to take very seriously. And all his work as associate dean and director of the Office of Minority Education. He led that program from 1995 until he retired in 2006. Leo was a guiding force behind this celebration for many years, and we are all very much the beneficiaries of his compassionate vision.

Now, Dylan and [? Zenzi ?] have both testified eloquently to the importance of the theme this morning-- deploying our gifts to the greater good. And we're going to hear more on this theme from our keynote speaker, Gerry Hudson. So I want to just take my time to focus on two ways that this idea of deploying our gifts intersects with the life and work of MIT. As [? Zenzi ?] described, MIT is a gift in itself, and one that each of us has a duty to use in service to the world. Yet as wonderful as the gift of MIT may be, intrinsic to its value-- and intrinsic to our understanding its value-- is a perpetual striving to be ever better. This is woven into the very fabric of the life at MIT.

A very important piece of our mission, and an important and constructive tool to help us build to a stronger MIT, is the recent report from the Initiative on Faculty Race and Diversity. I have to acknowledge the scale and scope of the effort, which, under the leadership of Professor Paula Hammond, the Bayer professor of chemical engineering, involved eight MIT faculty members who worked over a period of 2 and 1/2 years. They conducted extensive quantitative and qualitative research. And the report has many, many important observations, but it demonstrated, among other things that, through the search and tenure process and in their daily lives on campus, the experience of many of our faculty members from underrepresented minority groups is different from that of their majority peers. And sometimes, that difference is painfully obvious.

Clearly, to achieve a true culture of inclusion-- the topic on which I have spoken annually about, and you know my passionate about this-- to make MIT as valuable and effective as it can be, we still have much work to do. Fortunately, the report from this task force recommends the kind of practical steps that can accelerate positive change. They don't just talk about things in theory. They talk about things in practice. For example, it makes it clear that strong mentoring for junior faculty makes a tremendous difference. And yet, it finds that mentoring is a bit uneven across the Institute. Now, once MIT has succeeded in recruiting brilliant young faculty members to our campus, it only makes sense that we would give them the guidance that enables them to thrive here. Getting that process right will contribute directly to the excellence of MIT.

I want to quote now from someone who already has taken direct personal responsibility for creating a culture of inclusion. Professor Ed Berninger-- who's here this morning. I saw him. There he is-- who now heads the Department of Physics. For those of you who have not yet seen our new diversity website, please check it out. It's very exciting. And I'm going to quote from his blog on that website.

He says, "I am sometimes asked, why do you do this? Why do I spend time and energy promoting diversity and inclusion at MIT and in my profession? Two reasons. The first is an intrinsic sense of fairness and justice. And the second-- the key to turning idealism into effective action-- is that I learned how to be effective by mentoring junior faculty starting almost a decade ago. MIT attracts great talent, but does not always nurture that talent very well. A sink-or-swim environment will separate individuals, but can be terribly wasteful of human potential, and is generally harmful to morale. Good mentoring is at least as important as a financially adequate startup package for new faculty members." I would like it if we considered mentoring an essential part of the startup package for new faculty, and we're going to work on that.

As the first step in implementing the new report's recommendations, Provost Rafael Reif and Professor Hammond have already begun strategy meetings with the Academic Council, with school councils, and the heads of academic units. To translate the report's recommendations into actions on the ground, we'll begin by sharing best practices around faculty searches, recruitment, and mentorship. There are places where these things are done well, and it's important that those places where it's done well share their practices across the Institute so that, in Ed Berninger's phrase, people can "learn how to be effective" in creating change.

In broader terms, I also hope that the findings of this report will help make it easier for individuals and departments to think and talk openly about issues of race and how those issues affect them, because I believe, on this score, we really do have a lot of work to do. Since the report came out, though-- I have to be honest and direct with you all-- I've heard from a number of people that its findings and recommendations might somehow threatened to erode or compromise the excellence of MIT. I could not disagree more.

As I've said many times, MIT is and always must be a place with unrelenting standards of excellence. This report is not about compromising those standards. It's about reaching them. For almost 150 years, MIT has built and maintained its standards of excellence by bringing in the very best people and offering them an environment where they can do their very best work. Thanks to the Initiative on Faculty Race and Diversity, we have new information that will allow us to uphold these bedrock MIT standards, and strengthening MIT and this dimension is pivotal to helping us magnify and deploy our shared gifts for humankind.

That idea is not simply the theme of the celebration today. It's at the heart of the mission of MIT. Every day, the people of MIT, in profound ways, deliver on our mission to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship to serve the nation and the world. Every day, they use their exceptional powers of analysis and creativity to tackle some of humanity's greatest challenges-- from sustainable energy to drinkable water, from cancer to autism to AIDS, from the shape of our cities to the future of our oceans.

And so I'm pleased, but not at all surprised, to note that people are indeed using their gifts to respond to the terrible human tragedy that continues to unfold still in Haiti. And Dylan, thank you very much for calling this out. As he mentioned, many of our students are donating time and talent as well as money. MIT's Public Service Center is coordinating a range of efforts to channel funds and expertise to Haiti. And thanks to the work of two of our dedicated researchers-- Chris [INAUDIBLE] and Dale [? Hiwakim-- ?] since the earthquake, people in and connected with the Media Lab have used their technological skills and creativity to facilitate communication between Haitians here and in Haiti. And they plan to extend their work through the very long rebuilding process to help match the flow of resources to the actual areas of need.

Now, I have to tell you, I know of many of the efforts on campus to reach into Haiti to help in whatever way we can, but I am absolutely certain that I don't know of all of them. If any of you know things that I haven't yet mentioned and would like us to be aware of them, please don't hesitate to just shoot me an email so that we can add those activities to the growing list of efforts from MIT to help rebuild Haiti.

Let me close with a passage that bears special consideration for those of us who belong to an intellectual community like MIT. It's drawn from Dr. King's Nobel Prize lecture-- The Quest for Peace and Justice-- that was written almost a half century ago. To many of us here in the audience, that feels like only yesterday. But to others in the audience, it seems like an eternity ago, separating the younger part of our MIT population from the older part.

As Dr. King framed it, "modern man has brought this whole world to an awe-inspiring threshold of the future. He has reached new and astonishing peaks of scientific success. He has produced machines that think, and instruments that peer into the unfathomable ranges of interstellar space. He has built gigantic bridges to span the seas, and gargantuan buildings to kiss the skies. His airplanes and spaceships have dwarfed distance, placed time in chains, and carved highways through the stratosphere. This is a dazzling picture of modern man's scientific and technological progress.

Yet, in spite of these spectacular strides in science and technology, the richer we have become materially, the poorer we have become morally and spiritually. We have learned to fly the air like birds and swim the sea like fish, but we have not learned the simple art of living together as brothers."

In many ways and many places, Dr. King's words still ring true. The human family has certainly not yet mastered the art of living together. But I hope that perhaps we've learned something about the true human purposes of technology, and I'm extremely proud to be part of a community that is harnessing the tools of modern technology and science to serve the highest human purposes of connection, compassion, and kindness. And thank you all for joining me on that mission.

[APPLAUSE]

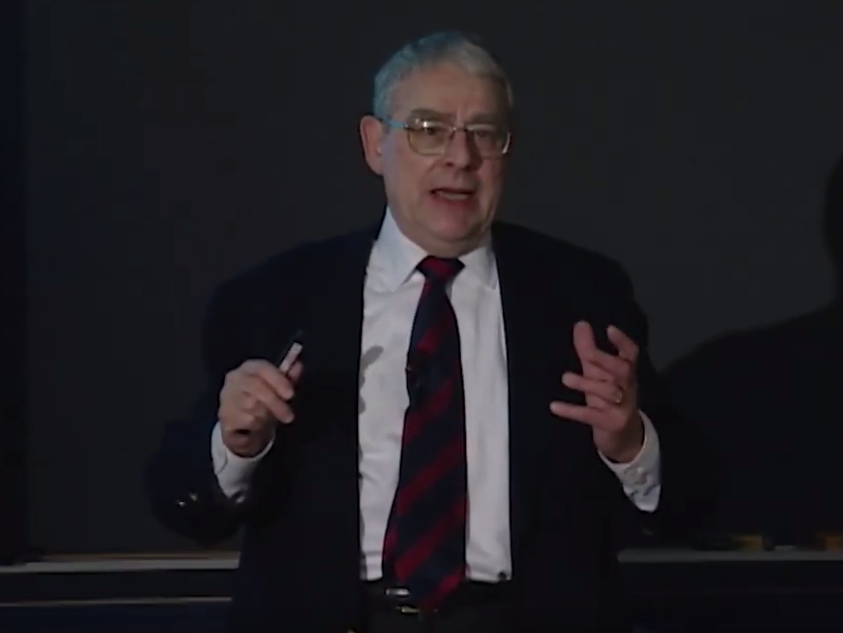

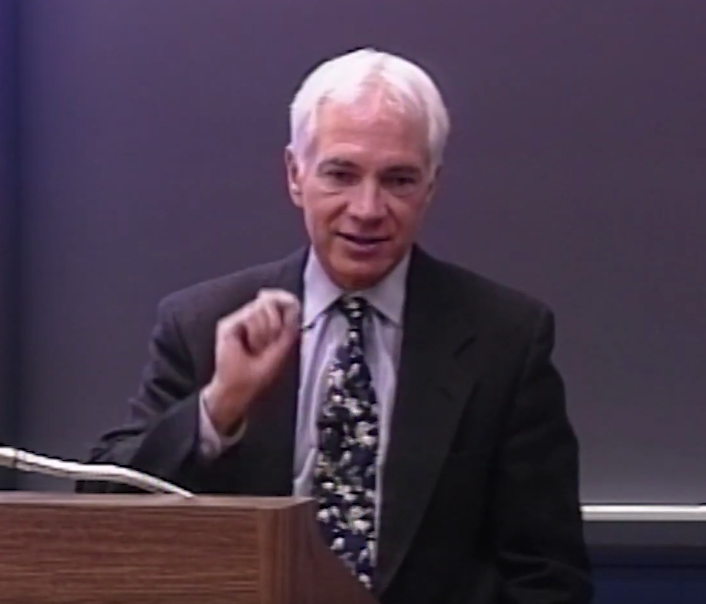

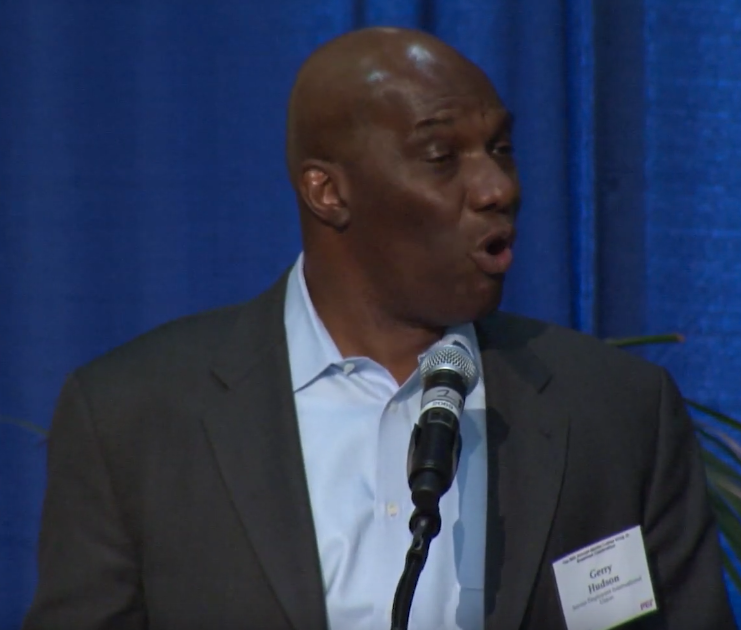

Now, for what I know I've been waiting for since I woke up very early this morning, it's my very great pleasure to introduce our keynote speaker, Gerald Hudson. He's executive vice president of the Service Employees International Union-- SEIU. With more than 2.2 million members, SEIU is North America's fastest growing labor union, and Gerry Hudson has focused his attention on advancing the interests of those who work with the elderly and disabled in long-term care.

A member of SEIU since 1978, Gerry has also made his mark with an ambitious commitment to combining social justice with environmental activism. He was part of the first ever US Labor Delegation to the United Nations climate change meeting in Bali in 2007, focusing on the disproportionate impacts of environmental degradation on low-income and minority communities. He served on the advisory board of the Apollo Alliance, a labor-based organization that promotes ways to create high-quality jobs in clean energy economies. And he served on the board of Redefining Progress, a leading think tank creating innovative public policies that balance economic well-being, environmental preservation, and social justice.

This morning, he's going to talk to us about one of his ongoing efforts-- an initiative he co-founded with MIT Professor Phil Thompson-- called Emerald Cities, something I know a little bit about, and it's very exciting. So I'm delighted that we're going to get an additional insight into that this morning. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Gerry Hudson.

[APPLAUSE]

HUDSON: Wow. These are some tough acts to follow. It's hard to inspire you when you inspire me so. So, let's begin. I want to start by thanking President Hockfield, Provost Rief, Chancellor Clay, and the Subcommittee on Race and Diversity for organizing this event. I want to also thank this institution, because whether you know it or not, I've made enormous use this institution for at least the last five or six years. So I want to, one, thank you, because you went with me and some other labor leaders in to New Orleans right after Katrina, where we thought that there ought to be more of a labor response to what was going on there, and that the whole of the labor movement really ought to look not to just responding to the call for relief, but also to respond by, in some ways, staying the course and trying to reconstruct that city.

And so with Phil Thompson, a whole team of MIT professors and students went in to New Orleans, and we began to build a proposal for rehabilitating the public housing in New Orleans. That proposal was so admired and respected by the labor movement at the time that the AFL-CIO pledged to give a billion dollars out of its pension funds to reconstruct public housing in Haiti. That was a labor movement that made a commitment that I was proud of.

The problem is that when we, in fact, made the proposal, we had a president named Bush who said, I'd rather tear the buildings down than allow you to rebuild them and invite back the residents of public housing. And so he turned us down, billion dollars and all. But still, you-- this institution, its faculty and students-- were there on the ground, and some of them remain on the ground in New Orleans to this day.

When I thought that it might be a good idea to try to force again this labor movement-- in which I've spent the better part of my working life-- to rethink its notion of leadership, and to rethink how it did its work on the ground connecting ordinary workers to each other, I also came back to MIT and found my friend Otto Sharma. And we spent quite a bit of time talking about the reinvention of labor leadership for the 21st century. So thank you, Otto, for that. thank you, Sloan Center, for its work.

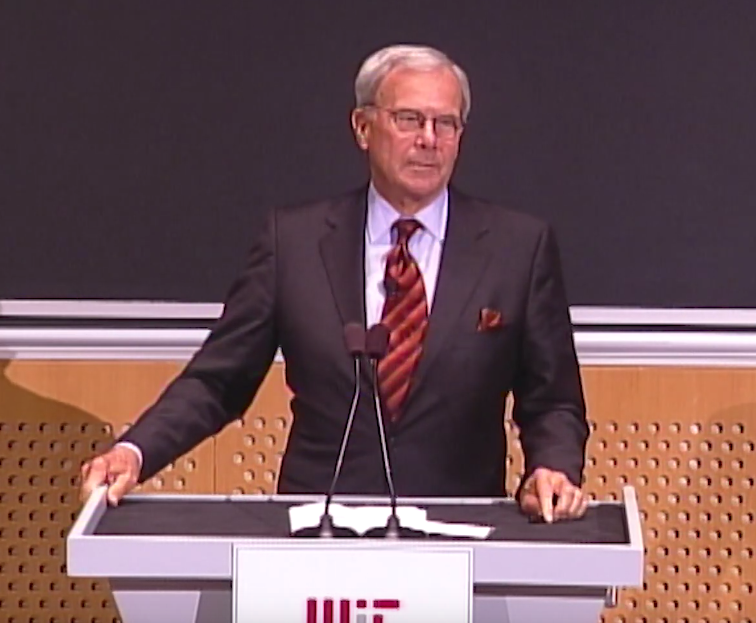

And then, again, when I started Emerald Cities and we weren't quite sure how we wanted to get Emerald Cities moving in the world, we had a lot of great and interesting people from the labor movement, people from communities of color all around the country. We had them all in one place, but we weren't quite sure how best to use them. And so I asked Tom Kochan to help me facilitate a meeting of that first retreat on green jobs, right here at MIT. And so I thank you, Tom, for that great work.

So I guess you can tell that MIT is one of those places where I come to do what the philosopher novelist Albert Camus says-- "find a respite for musing." I find you great partners in the act of musing-- musing about the great problems of the world and trying to find solutions to those problems. I always find big hearts, an open mind, and eager spirits here at MIT. And so I am exceedingly grateful, and the institution that I lead is exceedingly grateful, to the leadership, the students, and the faculty of MIT.

Dr. King. I had a lot of remarks that I wanted to make about King. King is my muse. King is the reason why I chose to be an organizer. If you know anything about the institution that I come from, you know that that institution is called 1199 in New York. And if you walk through the doors of 1199 in New York, as you come to through the door and you look to your left, there's a bust of Dr. King. And under it, there's a quote from King, and over it, there's a big picture of King talking at an 1199 rally.

Dr. King called 1199 his favorite union. It is the union that my mother, when she moved from the South as a domestic, she joined as a nursing home worker in New York. It is a union that has had a long tradition of combining social justice with the fight for economic justice. It is a union that understands that that is an odd bifurcation-- social and economic justice-- that the only way in which you can, in fact, do anything about economic justice is if you do something about social justice. A King-like vision. It is the vision that moved 1199 from its inception as a hospital worker's union in New York.

It is the union that was one of four unions that actually supported Dr. King in his call for a march on Washington. So you know, for me, it was a union that I am deeply proud of. And then one of the proudest moments of my life is when I was given the opportunity to serve that union. And I served it for 20 years as its political director, its communications director, and its education director. Dr. King, my muse.

I want to tell you that mostly nowadays, I don't do celebrations for King. I stopped doing them a couple of years back, because I could hardly recognize the King that I knew and love, whose writings I had read. I could hardly recognize him in much of the speeches that were given about him in some of these celebrations. And the only reason that I chose to come here to this celebration of King is because I think you get it-- that you get the real King message. The real King message. And so I want to talk to you about that message.

It's a message that, if you go back in the writings of King, one of the most interesting places to stop is a speech that he gave in 1961. It's rarely quoted, rarely talked about. But it was a speech given before the AFL-CIO. It's interesting what prompted the speech, because for years inside of the AFL-CIO, there was a grand old gentleman named A. Philip Randolph, who had been working inside of the AFL-CIO and insisting that the AFL-CIO deal with the question of diversity, deal with the question of race and racial discrimination in the labor movement. He had been working and toiling on that issue for some 25 years by the time King gave the speech that he gave.

If you remember, '61 is six years after Montgomery. It's two years before the march on Washington. And he gave a speech that was suggestively entitled, "When the Negro Wins, Labor Wins." The reverse is also true, and he suggested it in that speech. If the negro loses, labor will lose. He suggested that, in that speech, what he was about was not just an opposition to white supremacy and racism in America-- that what he was truly against was war and poverty, that we would achieve the good society, the just society, when we rid the world of war and poverty, and that the achievement of civil rights was merely a means to the building of the right kind of movement that could, in fact, rid the world of poverty and war. That was the King that spoke before the AFL-CIO.

And he then implored them to come with him on a journey through the South to eliminate white supremacy, and to use the victory over white supremacy in the South as a jump-off point for creating a coalition of conscience. And I should tell you, that meanie who led the AFL-CIO at the time, and most of the affiliates of the AFL-CIO, did not heed Martin Luther King's call. The Negro was asked to go off and to fight Jim Crow on its own, without labor's support.

He left that convention and he made a trek around the country, talking to unions everywhere and in union halls everywhere, convinced that a-- as he put it-- Negro-labor alliance was fundamental to creating a progressive politics in the country. And he invited them to join him on the March on Washington, demanding an end to Jim Crow. And people forget this. It was freedom and jobs. Freedom and jobs. It was not just about civil rights, but it was about economic justice as well. Freedom and jobs. Come with me. Sad to say that, of all the unions of the AFL-CIO, only four-- only four-- were willing to take that journey.

I start with that King because I think the failure of a labor movement to see the cause of black folks demanding an end to white supremacy and demanding economic justice in America, the failure of the labor movement to join with that movement, is what gave rise to an ugly politics that has swept this country for more than 40 years, because if you remember that right after we got the Voter Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act-- Civil Rights Act of '64, the Voting Rights Act of '65-- something really interesting happened in the country.

Rather than the labor movement and everybody joining with black folks and trying to use the franchise, and trying to use it in a way to bring about a progressive politics in the country, instead, Dixiecrats started to flee the Democratic Party in droves. And by the time you get to '68, when King was murdered, an interesting man that King used to encounter in the South was moving all about the country, picking up supporters everywhere.

Those of you who are as old as I am will remember that that man was George Wallace. You met him as governor of Alabama, and by '68 Governor Wallace was running for President and picking up supporters in places that were interesting-- democratic strongholds. Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio. Suddenly, they were supporting Governor Wallace. And if you go back to that year, you know that the Democrats, for the first time in a long time, lost the Presidency of the United States, and Nixon was elected.

And I would submit to you, the long nightmare of American politics begins there. I see it as the failure of all of those places, because what makes Pennsylvania interesting, what makes Michigan interesting, what makes Massachusetts interesting, is that they were strongholds of the labor movement. And all of that white working-class movement went one way in reaction to the victory of black people in the South, and Republicans came to power and began a nightmare politics that lasted 40 years.

When the Negro loses, labor loses. And if you think about these past 40 or so years, you will also remember that the labor movement went in decline. At the beginning of the period when King was making his call, labor with some 33% union density in the country as a whole. At the end of this nightmarish politics, union density in this country is now at 12%. 12%, with private sector union density at 7.5%. If the trends continue, there will be no labor movement in 20 years in the country.

And with the labor movement has also gone income. Look at where we now are-- the most outrageous concentration of wealth in the history of the country, with the top 1% owning as much as 34% of the nation's wealth. Outrageous inequality. Outrageous inequality, presided over by a right-wing Republican politic that was created, I would say, way, way back when labor refused to join hands with the Negro and start the trek towards the creation of what was truly Martin's dream-- which was to create a world in which every human being, no matter who they are, had a right to flourish. Had a right to flourish.

And he believed that it could only be brought about-- go check the text, that text that I reference. And I would suggest that, for a real good look at the vision, go check another text. It was "Where Do We Go From Here?" Chaos or community? Chaos or community? Because in that text, you see him struggling with how it is that we not only deal with white supremacy and then move on to deal with poverty and war in this country, but have him doing it in the rest of the world.

And he ends the book with a long conversation about the world house. Science has now made us smaller and more interdependent, he said. That requires that we learn to live together in some new way. President, you had a wonderful quote, because he suggested that while we made all this progress in science, we had made too little progress in matters of the heart, and had not yet learned as a people to live together.

I say this is a timely moment to remember that King, because it was that King that was most recently invoked again. If you go back to 2008, to Colorado, and you remember Barack Obama, acceptance of the nomination of the Democratic Party, that whole acceptance speech was prepared by a recollection of King. The whole thing. He brought King's children on stage. He made all kinds of references to King. It was almost like a passing of the baton.

I've often said to Phil Thompson, one of my dearest friends, that when Martin's generation passed the baton to us, having dismantled Jim Crow, having put a vision out there, I was worried that we dropped it-- that we had dropped the baton at a crucial moment when we should be advancing.

But on that stage with Barack Obama in 2008, I was persuaded that maybe, just maybe, our generation had picked up the baton, and that we might for the first time, given all of what was in that stadium-- young people from all over the country, of all races, all in there having worked their tails off to get to that moment with Barack Obama, labor movements who had fought themselves, argued among themselves for months, were finally together in that stadium celebrating this man who said, I will create a politics of hope to fight against the politics of division and fear and hate that has ruled the country thus far. I will bring into existence a politics of change that you can believe in. It was a remarkable passing of the baton.

One year later-- one year later-- I'm worried about that politic of hope that was so eloquently spoken about on the stage in a stadium in Colorado. I'm worried about it. We promised change, but change didn't come. And you in Massachusetts know a little bit about the why of it.

But what I've learned in this year, what are all of the great issues of my life-- from healthcare reform to green jobs to labor law reform, all of these things that I've struggled and I thought were essential planks in a progressive platform, all of these things were on the national scene-- a President can't bring those things about. He can want them. He can ask for them. But he can't make them happen. That takes you. That takes me. That takes all of us. There will be no change in America. We will not create a more just America in which wealth is more equitably distributed, in which every child, no matter who or where they are in this country, can flourish and use all of the gifts that they have. There will be no change that brings that America about unless you use your gifts-- put your gifts back on the field.

I believe, having spent 20 years with the members of my own union, in the incredible ability of ordinary men and women to move mountains when they decide to do it. I've watched my union do incredible things when they decide to collectively put their shoulder to the wheel.

So I say to you, MIT, we need your gifts put out there one more time to try to realize the possibility of a more just America. It will not happen unless you put your gifts on the table. And knowing what I know about the gifts in this room, if you put them on the table, we'll get there. Thank you so much for all that you do. Thank you so much for all that you will do.

[APPLAUSE]