Noam Chomsky & Paul Farmer, “The Uses of Haiti" - MIT Technology and Culture Forum

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MODERATOR: Good evening. My name is Erica. And as president of the MIT Western Hemisphere Project, I would like to welcome each and every one of you for coming to tonight's event entitled The Uses Of Haiti.

What I would like to briefly discuss with you right now is just to mention that this event was co-sponsored by the MIT Western Hemisphere Project, MIT Student Pugwash, and the MIT's Technology and Culture Forum. As you can see up here on the board, there's three coming events. Two are tomorrow.

One is an evening of Latin American chamber music and a Pugwash student conference entitled Technology in the New Global Context, Rethinking Social Responsibility. I encourage people to attend those events. And the Western Hemisphere Project will be having an open meeting within the next two weeks.

Okay, briefly to discuss, I'd like to mention that our schedule for this evening is as follows. First, I'll give introductions, introduced Nancy Dorsinville, who will introduce our two speakers this evening, Dr. Paul Farmer and Professor Noam Chomsky.

Professor Chomsky will speak for roughly half an hour. And Professor Farmer will speak for roughly half an hour and will be followed by questions. And, now, I'd like to begin with an introduction.

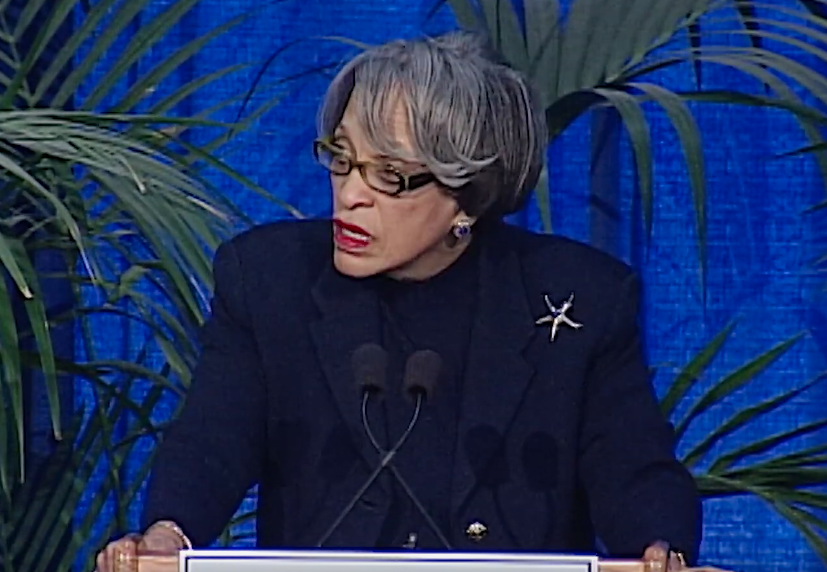

As a research fellow at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Nancy Dorsinville's work focuses on health and social justice issues within the Haitian diaspora. As a social anthropologist with a specialization in migration studies, she lectures on women's health and violence at the Harvard School of Public Health. Her research also includes domestic violence as a public health concern among Haitian woman.

She's presented her work at a wide range of academic and international conferences, most recently at the UN Conference against Racism in Durban on the intersection of migration, xenophobia, and violence against women. She is a member of Partners in Health, an advisor to women's program at the UN Academy and an affiliate at the Harvard Program in International Analysis and Conflict Resolution. Currently, she is a faculty advisor for the Harvard Haitian Students Alliance. And now with great pleasure, I would like to present to you, Nancy Dorsinville.

[APPLAUSE]

DORSINVILLE: Good evening, everyone. I'm very happy to be here. And I thank you for being here to join us in hearing and learning and expressing concerns about the present conditions in our beloved Haiti. The two people here with us this evening don't need much introduction.

Dr. Farmer, as you know, has been working in Haiti for the past 20 years in infectious disease, but fundamentally addressing issues of the poor. From a systemic standpoint, from of spiritual standpoint, and from an economic development standpoint, his work is very much rooted in the actualization and the empowerment of the more marginalized people in Haiti of which our population has the highest percentage. So I take this opportunity to thank him for a lifetime of dedication to my countrymen and, particularly, the most disadvantaged of my countrymen.

I then would like to attempt to introduce Professor Chomsky, who has written extensively on a number of issues. But, particularly, our focus this evening is the impact of American or US foreign relation on the current situation in Haiti, namely the economic embargo. I just want to contextualize our discussion this evening with some remarks.

And I would like to start by echoing something that Dr. Farmer has said consistently in his writing and his well-attended lectures on the other side of the river that what's happening today in Haiti, the economic embargo, is the result of a series of historical antecedents that cannot be taken out of the equation if we are to really look at what the circumstances are. In addition to that, I think it's important to understand, as Professor Chomsky has also said repeatedly in his writings, that democracy is a process. And the outcome of democracy requires a series of fundamental conditions, namely that the sovereignty of the people has to be respected.

The agency of people in making certain choices about the kind of governance that they have, how that governance will be applied, and who they will answer to has to be part of their agency and has to be part of their choice. I think on the eve of our bicentennial independence, the question for me is what does it mean that today we are under economic embargo. What does it mean that as the-- I mean, everybody calls us the poorest country in the hemisphere. And a lot of people have contentions about that.

I would rather say we are the most impoverished country in the hemisphere, because it has happened systematically with very deliberate, intentional policies that have led to the impoverishment of Haiti. One of the things that's very topical today, people talk about reparation. Well, not only were we the first country to be under embargo when we became independent-- which that, too, was a process. But the embargo allowed the US and its allies not to recognize our sovereignty for about 60 years. And yet during that time, selectively, there were trade agreements that benefited the countries of the north, while beginning what we see today as the most impoverished nation in the hemisphere.

A lot of prerequisites have been put on why we haven't gotten the $500 million in loans and grants that were approved. A lot of it has been relegated to, allegedly, problems with elections. Well, I think the other oldest republic in the Americas also understands what it means to have problems with elections.

The other issue that's been put forward is that our cabinet was not pluralistic enough. And in the name of democracy and in the name of diversity in our cabinet, it was important to change certain senators. Every time they came up with a different prerequisite which we fulfilled as a sovereign state, something else came up.

So I've thought about this a great deal. And I thought, you know, this is becoming like a kaleidoscope of democracy. And the colors are changing. The shapes are changing. The demands are changing.

And we're not getting a fixed picture from the powers of the north as to what it is that they want in order to release the funds, which are hampering any humanitarian endeavors, any humanitarian initiatives, and any real fundamental systems and building blocks for the democracy that we've fought for from the very beginning. 2004 is just around the corner. And our struggle for democracy began way back 200 years ago.

And we have had a fixed picture about what democracy means. We still have a fixed picture. The people of Haiti have spoken. We have heeded the prerequisites of the changing shapes of the changing demands. And, now, in the name of Democracy with big D in the name of humanitarian concerns, which seems to be the epitaph for everything that's being done today in the world, we demand the release of these funds. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

So, now, Professor Chomsky is going to talk to us and share his thoughts about the implications of American foreign policy on the economic embargo imposed on our country today.

[APPLAUSE]

CHOMSKY: Glad to learn what I'm supposed to talk about. That's fine. Well--

DORSINVILLE: Anything will do.

CHOMSKY: Anything will do. I understand.

[LAUGHTER]

Well, let me lead in from the last talk I gave, which was last night in New York where I had to be taken out under police protection. You can guess what the topic was. It was about the Middle East. Tonight, if anything controversial comes up, I'm going to hand it over to Paul, so he can--

[LAUGHTER]

Well, a word about the Middle East--

[LAUGHTER]

--maybe, just so I can have some continuity--

[APPLAUSE]

--a very short word. You may have seen kind of an interesting article in The New York Times Magazine a couple of weeks ago by Deborah Sontag on the Palestinians. In it, she made a good point. She was talking about the difficulties of discourse between Palestinians and the West and why it never seems to work.

And the problem that she pointed to is quite real. She said, the Palestinians keep harping on history, where history means anything that happened more than about 5 minutes ago. And the West doesn't want to waste time on all this sort of old fashioned boring nonsense, but just get on, so that the West can lead the way to a glorious future.

And that makes discourse really hard. And, actually, that point generalizes all over the world. Those who have their boot on somebody's neck never want to know how it got that way.

That's boring, old fashioned, dusty, old stuff. Let's just go on with our boot on the neck and make it even better. But the ones who have their neck under the boot, they somehow have a different view of things. Because they're backward and uncivilized and, you know, that sort of savage, you know.

Well, I was asked to say a couple of words about the background, including the history, meaning what happened more than 5 minutes ago, which puts me on the side of the victim. So that's good. I'm happy to take that position. That's a position we ought to take, not necessary to say.

As far as democracy is concerned, I think it's very clear why Haiti doesn't meet the standards of democracy, the same reason it didn't meet the standards 10 years ago when it had its first democratic election. The election just came out the wrong way. The US was certain, confident, that the election would be won by its candidate, a World Bank official, who would lead the country, you know, on to this brand new era of neoliberalism that had already had a certain history in Haiti.

He got 14% of the vote. And out of the woodwork, came a populist priest who got 2/3 of the vote without any funds or any publicity or anything else. Because things had been going on in the country that nobody paid any attention to.

They were in the slums or, you know, in the hills and places where no real people live. But they had organized, you know, a vibrant democratic society, maybe the most democratic society in the hemisphere or maybe in the world, but on their own, you know, without control from above. And that doesn't fly. You know, that's not democracy.

It's not for us or anyone else. And, furthermore, this is pretty official. So instead of quoting myself, I'll quote a real expert. Thomas Carothers is the best known scholar on issues of the emerging democracies in Latin America.

He's written a standard work. And he writes from an insider's perspective. He was part of the Reagan State Department involved in what they called democracy enhancement programs.

So when he writes on the effect on, you know, bringing democracy to Latin America, he writes from both as a scholar and as an insider. And he's pretty honest about it. He says that the Reagan policies were very sincere, but they failed.

And they failed in a curious way. He said, in the areas where US influence was least-- namely, in the southern cone of Latin America-- there were real steps towards democracy, which the Reagan Administration tried to prevent, but wasn't able to prevent. They sort of happened anyway.

In the areas closer where the United States has much more influence and control, in effect it has basically run it for a century or more, the policies still were sincere. But they just didn't work. And the reason was that the United States, he says, wanted top down democracy, in which the traditional ruling elites who have been associated with the United States remain in power, but under democratic forms. And, in a sense, that was achieved. But, you know, as an honest person, methinks that's not real democracy.

But he's correct. That's exactly what the United States wants. And you'd expect any powerful state to want some kind of formal democracy, because it sort of looks good. But top down forms in which traditional elites, those who have concentrated wealth and power in their hands, because of their alliances with the boss in the West-- us, in this case-- they have to remain in power. Incidentally, the same picture is held for the United States itself or always has been back to the Constitutional Convention.

So that's the picture for us. And it's got to be the picture for everyone else. There's even a technical name for it in the academic literature.

It's called polyarchy. So theorists of democracy argue that we ought to have polyarchy, not democracy. Polyarchy means small groups of elites. What James Madison called the wealth of the nation, the wise section, those who have sympathy with property and its rights, they ought to rule. The rest ought to be factionalized.

They are allowed to participate, because it's a democracy, but periodically. They participate by every once in a while coming out and lending their weight to one another of the responsible men who represent the wealth of the nation, those who have the interests of property at heart. That's the way this country is supposed to run.

That's the way every country is supposed to run. And that means, if a populist priest comes out of the woodwork with 2/3 of the vote without any money or any publicity just basing himself on grassroots organizations that aren't supposed to exist, that's not the right kind of democracy. So, of course, it has to be stopped.

And that standard-- Haiti, still, they're kind of backward and uncivilized and haven't figured this out yet, though the United States has been trying to teach it to them for a long time. Well, I'm-- say a few words about history. Those of you who've taken a history of course in junior high school will remember that half a millennium ago a group of savage barbarians in the west of Europe launched an assault on the rest of the world and have practically devastated it ever since.

One of the first places they came to is, in fact, Haiti, which they were overawed by what they found. They regarded it as-- the Spanish, this is Columbus. Las Cases, the great contemporary historian, described it as the most densely populated part of the world, which could happen true.

And they were overwhelmed by the wealth and the peaceful population, maybe 8 million people or so. And they just couldn't believe it. Well, the current Haitians can't remember what happened to the original, to those who Columbus found. Because they were wiped out within about 25 years or so.

They just were no good as slaves and so on. And they brought in African slaves to be able extract the wealth of the country and send it back where it belongs, namely to the savages in Western Europe. And it did.

Haiti was the richest colony of the world. Perhaps, it was the only comparable one also discovered so-called pretty early. It was Bengal, which, when the English came, they were also astonished at its wealth and advanced industry and so on.

And it's maybe an oddity that the two symbols, very symbols of disaster and impoverishment today, are Haiti and Bangladesh. That is the two richest areas, maybe the two richest areas of the world, and the longest under Western rule. Actually, that generalization kind of extends to the Western hemisphere itself.

In the 20th century, Haiti has been the leading beneficiary of US intervention, all kinds-- military, military occupation, you know, aid, experimental programs, scientific approaches to how to do things. And, oddly, it's the most impoverished country in the hemisphere. There are two countries that vie for second place.

Every year, they shift a little. They're Guatemala and Nicaragua, which, by accident, happen to be the second major targets of US intervention in the hemisphere. That's another one of these odd accidents, like, you know, the fate of Bengal and Haiti over centuries that you would only know about if you took a real course in history.

Then it would be taught in junior high school and the implications of it. And it goes on from there. This is not the only example.

Haiti was incredibly rich. It was producing about 3/4 of the sugar in the world and all sorts of things, but producing it for the conquerors. A large part of France's wealth comes from Haiti just as a substantial part of England's wealth comes from Bengal and other areas it conquered and left completely devastated, of course.

200 years ago, the Haitians did make a serious mistake. They carried out the first and only revolution of the 18th century. It's the only one that met the conditions of the Enlightenment. That is it called for universal freedom.

None of the others did that. The French and the American Revolution, obviously, didn't qualify. And that appalled civilized people. It appalled them so much that there apparently was no discussion in France, or in England, or the United States of the very idea that black slaves could liberate themselves. It was just too appalling.

When they finally succeeded at a horrifying cost, well, Tallyrand, the great French statesman wrote to James Madison that all civilized people must be horrified at the sight of armed Negroes carrying out massive atrocities against the French, you know, who just really belonged there and driving Europeans out of their country. And that was, in fact, the view. I mean, Haiti was punished, as you said.

It was punished by being forced to pay severe indemnity to France for the crime of having liberated itself. That's not the only case, incidentally. Again, as I'm sure you learned in junior high school, when George Washington in the middle of the Revolutionary War decided to wipe out the Iroquois civilization, which was in many ways more advanced than the colonists except in modes of warfare, he succeeded.

But they had to pay an indemnity, too. DeWitt Clinton, the governor of New York, made a treaty with them after a sufficient bashing. And they demanded and had to do it that they compensate the colonists for the crimes they had committed by resisting the assault that Washington's forces led against them. This was right during the Revolutionary War, incidentally. And it's not the only time.

In the 1980s, the US was ordered by the world court to pay substantial reparations to Nicaragua for the crime of international terrorism for which it was condemned. But power relations turned it the other way around. Nicaragua pays indemnities to us.

The Vietnamese have to pay the United States the costs of running the client regime in South Vietnam. Literally, that's what's happening. And that's the way power relations work. Haiti's a particularly grotesque example of it, but it's true.

Finally, the US did recognize Haiti, was the last major country to do so. And it was 60 years. It was 1862. And there was a reason. It was right in the middle of the Civil War.

They were going to liberate the slaves. And there was a problem about what to do with them. We had to satisfy Thomas Jefferson's dictum that the country had to be, as he put it, free of blot or a mixture of red or black.

Well, the red part was pretty easy, just exterminate them. But the black part, they were hoping that they could be sent somewhere. In fact, the United States recognized Liberia in the same year, 1862. The idea is, well, you sort of get rid of these savages who don't belong here.

And that was the context in which Haiti and Liberia were, indeed, recognized. The latter part of the 19th century, the European powers and the United States were jockeying for control of the Caribbean, which was a very central area in world affairs. For one reason, because it was the main source of soft drugs-- tobacco, rum, sugar, which were very badly needed in order to pacify the working classes in England and others who were benefiting from early industrialization by being devastated themselves.

And a lot of the wars of the period were, in fact, fought over the Caribbean for those reasons. Actually, the same story goes on in India, but I don't want to get too far off. The British actually were running the biggest narco trafficking enterprise in history it turned out in the late 19th century, interesting story for that reason.

[LAUGHTER]

The end result of it was that the US became the dominant power by the early part of the last century. And Haiti was still considered a very important colony, plenty of wealth worth having. Woodrow Wilson invaded it in 1915. It's an example of what's called until today Wilsonian idealism.

He invaded Haiti and the Dominican Republic. And, here, the memories split. You know, the Haitians remember it one way. The United States remember it another way.

When Clinton sent the Marines in 1994 to restore democracy-- I'll get to that-- there was a lot of discussion in the press and scholarly literature and so on. And there were a lot of warnings that Clinton ought to be careful before following the course of Wilsonian idealism, which tried to impose order in this savage place in 1915. And, in fact, The New York Times even compared the problems he was facing to those of Napoleon in the early 18th century.

Napoleon and Wilson, both idealists, were trying to impose order on savage places where the people have homicidal tendencies and have no experience with democracy, like Napoleon had--

[LAUGHTER]

--and have no savagery, like the United States has. You read this right in the main columnists in The New York Times and Washington Post. And we have to be really careful about that, because these savage gangs with their homicidal tendencies-- on the one hand, the Tonton Macoute who kill, I don't know, tens of thousands of people under the Duvalier dictatorship.

And another one was the military junta, which the US was actually supporting, but was pretending to be opposed to, which it killed I don't know how many, maybe 5,000 people. And then the third homicidal gang was the peasants in the hills and the people in the slums, who had conducted, you know, who had really made this hideous error of having voted in as president somebody was going to carry out reformist policies. So between these three gangs with their homicidal tendencies seeking revenge in the traditional Haitian fashion-- you know, barbarians who don't understanding anything about civilization and stuff, which is exactly the way it's discussed-- the US should be cautious.

From the US point of view, the Wilsonian occupation was benevolent. So in 1994, leading historians like David Landes at Harvard explained that this was a period that really brought many benefits to Haiti for the first time. But as he pointed out, even the most benevolent occupation does sometimes arouse resentment. So the Haitians kind of didn't all totally applaud. And others chimed in with the same story, other distinguished figures.

And the State Department had explained at the time-- and this goes into history-- that many of the measures that Wilson introduced were, indeed, very benevolent. So, for example, they induced the Haitians, as the State Department put it, by rather high handed methods. I'll come back to those.

But they induced the Haitians to accept progressive changes in the constitution. See, these backward people had laws which prevented foreigners from buying up the entire country. And that is very unprogressive. And it's obvious why.

Anybody who's taken an economics course would understand the State Department reasoning. Obviously, to develop, Haiti needs foreign investment. And you can't expect US investors to put money in there unless they own it.

So the best way to raise Haiti out of its backwardness is to change the constitution to allow Western, means US, corporations to buy up Haiti's lands. And what were the high handed methods? Well, the high handed methods were to send the Marines in to kick out the parliament and then to write a constitution.

The author or the person who took credit for the constitution, though probably falsely, was Franklin Delano Roosevelt who, incidentally, hoped to make a killing on it himself by buying up some Haitian lands. The new constitution was presented to the Haitians for a vote, because we're a democratic society. And it was voted in by, I think, 99.9% of the 5% of the population who voted.

[LAUGHTER]

So the methods were kind of high handed, but benevolent. And it was also necessary to impose order. There are these savage gangs with homicidal tendencies. So the Marines had to restore order.

And according to the internal Marine investigation, they killed 3,500 of them. According to Haitian historians, they killed and 15,000 of them. But in any event, they killed enough so that they put down the resistance that even the most benevolent occupation elicits.

They essentially reinstituted slavery. They forced labor. There was some road building mainly for the corporations that were coming in to buy the place up. And, indeed, a lot of it was bought up by the West, very progressive. West means mostly US.

And they left the country after 20 years in the hands of a murderous National Guard trained armed by the United States run by dictators. Exactly the same thing happened in the next door Dominican Republic, except, in Haiti, it was a little more vicious. Because there was plenty of racism with regard to the Dominican Republic, but they were only spics and dagos in the terminology that was used, whereas, in Haiti, they were niggers.

And, worse, they were uppity niggers. So Wilson's secretary of state thought it was really comical to see, as he put it, niggers talking French, you know? Like, this is really funny.

And they really had to be put down. So it was sort of similar in the two countries, the two halves of the island, but much more vicious in Haiti. After that comes a period of US domination from a little bit of a distance.

So the Marines finally left after 20 years, but the US kept control. This is in the '30s now. At that time, Haiti, according to US agricultural producers, Haiti was producing cotton, for example, more efficiently than the United States was.

But that's no good. They had to be taught scientific methods of agriculture. So during the Second World War, when the United States needed rubber and other commodities for the war effort, it just took over large parts of Haitian agricultural lands and turned them over to scientific methods of production of rubber and other crops, total failure.

A couple of tons of rubber came out, but the country was devastated. When peasants were finally able to go back to what used to be their lands, there was a scraggly desert. You know, trees had been destroyed. The irrigation head been destroyed. And there was nothing there-- only the first of a number of scientific experiments.

There were others. Meanwhile, it was under US-backed dictatorships. In the 1970s, the World Bank and USAID decided to lend their assistance to this backward country. And they initiated a course of economic development that was going to turn Haiti into, as they put it, the Taiwan of the Caribbean. They really had a bright future ahead of them.

[LAUGHTER]

The method was to destroy wasteful activities, like agricultural production for your own use-- because, again, if you've taken an economics course you know it's much more efficient to buy highly subsidized US agribusiness exports instead of wasting your time producing your own food or producing anything else. And the idea was to turn Haiti into an assembly plant, essentially, for US corporations, who were very happy to use Haitian workers. They said they're very docile and disciplined, especially when they've got a military dictatorship and an army sitting on their necks.

And they are much cheaper than the ones in, say, Panama and other places where, you know, we haven't had that much progress. And, in fact, this went along with other experiments. Like, for example, USAID-- Paul's written about this-- a lot of the Haitian peasant economy was based on a very hardy breed of pigs.

They were used not only for food, but it's whole big part of the culture. But the scientific agricultural experts decided that these pigs might be susceptible to swine flu. Although, there wasn't any.

So they decided the best idea would be to wipe them out, which they did, and replace them with better pings, ones from Iowa. So they brought in fancy pigs from Iowa, which is that what they're called, white pigs? Yeah, white pigs.

[LAUGHTER]

And they're great as long as you keep them in air conditioned places--

[LAUGHTER]

--and, you know, feed them the very fancy food that you buy from US producers, you know, at a high cost. So you can actually keep one of these pigs, apparently, if you have an income about, I don't know, three times that of the annual income of a peasant in Haiti. That was another contribution.

Meanwhile, the economic miracle proceeded. Haiti was on its way to becoming the Taiwan of the Caribbean. During the 1980s, wages dropped by about 50%.

Haiti was self-sufficient in rice, virtually in effect, a pretty efficient rice producer and could have been better even. But that's inefficient. So they were forced to adopt the standard neoliberal package, you know, structural adjustment package. Cut your tariffs, privatize, that sort of thing.

The result was that Haiti now produces, I don't know what it is, maybe 50% of its rice, maybe less, something like that. Because Haitian producers, no matter how efficient they are, cannot compete with US agribusiness, which is getting 40% of its income from subsidies, government subsidies under the Reagan Administration. Remember, this is free market theory, which has a traditional form.

It's markets for you, but state protection for me. You know, that's the way it's run for hundreds of years. And that's why the world is divided into a first world and a third world. Actually, that's literally very close to true.

So Haitian peasants, of course, can't compete with highly subsidized US agribusiness. And they were wiped out. Now, in the neoliberal order, this free world that we live in, Haiti has a remedy.

They can impose anti-dumping restrictions on the United States. That is they can threaten the United States that they'll close the Haitian market to US exports the same way that Clinton does, for example, when US consumers prefer Mexican tomatoes or Japanese supercomputers. He can just close the market to Mexico and Japan unless they threatened to do so, unless they stop exporting. And then they stop for odd reasons.

And Haiti can do the same to the United States. Because after all, it is a free system. You know, it's the World Trade Organization rules. But for some reason, they didn't do it. I didn't figure out why.

But so Haiti was, in fact, devastated by this experiment again. Finally, the US was supporting the dictators all the way through until the last minute when even the army turned against them, at which point the United States decided that there should be a transition to democracy. Then came out-- I won't go through the details-- but the build up to the election, which was certain.

You know, they were certain that the US candidate would win. There's no way he could fail to win. And it came out the wrong way. And the US instantly changed policies.

USAID was diverted away from the government towards anti-government agencies. Every effort was made to undermine the government. Aristide came into office in February 1991.

The refugee policy was changed in radical violation of international law and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Carter Administration had begun barring people who were fleeing from the paradise that the US was creating, essentially not unusual. Take the Mexican border.

The Mexican border is artificial, like every border. It's the result of conquest. And it's been very porous throughout its history until 1994. After NAFTA, the border was militarized under Clinton's Operation Gatekeeper.

And the reason was because the effects of the economic miracle in Mexico were going to drive hundreds of thousands or maybe more impoverished devastated people north, and that had to be stopped. Because it's our conception of free trade. It's for capital, not people.

And the same was true in Haiti. As the economic miracle was put into effect, people started fleeing in desperation. So the US Coast Guard and Navy blockaded the place under Carter and just sent them back.

They were fleet fleeing real persecution as well as impoverishment. But US sent them back. Under Reagan, that was turned into a formal treaty with the Duvalier dictatorship.

But in 1991, the US reversed it. An independent democratic government came in. The flow of refugees virtually halted. In fact, it turned the other direction as people were going back in a moment of hope.

But at that point, any refugee who did come was granted asylum, no more sending them back to Haiti. So for seven months, until the military coup, the policy on refugees reversed. After the military coup-- went back to the old policy.

Bush, again, started returning the refugees. Clinton harshly condemned this in the 1992 election. And as soon as he got into office, he made it even harsher.

The government, actually, in the seven months it had, it was getting considerable praise from international institutions, even from secret State Department reports that were leaked. It was for progressive measures, for eliminating needless bureaucracy, for getting rid of oppression, and so on. They were getting substantial loans, in fact, which made it even worse. Because the country might fall out of US control.

A military coup came along. The Organization of American States declared an embargo. The Bush Administration almost immediately undermined the embargo by exempting US producers, which happened to include plants owned by the Haitian elite, the rich Mevs family and others.

They were excluded from the embargo and imports were allowed in. The explanation for this was, again, our benevolence. The New York Times explained that this was what they called fine-tuning the embargo to help the people of Haiti by exempting US exports. The people who they were helping were bitterly protesting. And the military junta and its wealthy supporters were overjoyed.

But it was all done for the people of Haiti just as we've always done. It got worse under Clinton, considerably worse. Furthermore, both the Bush and the Clinton Administration authorized the Texaco Oil Company to violate presidential directives and provide oil to the junta.

Anybody who was there could see the oil coming in, but the US government and CIA testified to Congress that no oil was coming in. You know, those oil farms that you saw didn't exist in the picture. It turned out the day before the invasion to restore democracy it was revealed that both Bush and Clinton had authorized that oil as the centerpiece of the embargo.

Also, the US was arming and training Haitian officers. The head of the paramilitary organization, FRAPH, which is responsible for thousands of deaths, was on CIA payroll. It's kind of conceded by now.

So, officially, the US was opposing the junta. In fact, it was supporting it. Then it restored democracy after they thought the popular organizations had taken a sufficient beating and thousands had been killed and they had been sufficiently terrorized.

And the terror was extreme. I don't want to talk about it, because you know much more than I do. But I was there for a few days at the peak of the terror. And, you know, I've been in places that are under severe repression.

I just came back from Turkey a couple days ago where, in the Southeast where I was, there's 15 million people living in a dungeon in an area where millions of people have been driven out of the surrounding region which has just been devastated in some of the worst ethnic cleansing and atrocities of the 1990s for which you and I paid, incidentally. This was done with US support and military aid. And that's why you don't hear about it. Yeah.

But, you know, the people that are under severe repression-- police everywhere, army everywhere. But there or other places, I've never seen anything like what I saw in the slums of Haiti back in 1993 when people were literally afraid to talk. The only thing they would say is things like there are eyes everywhere. You know, I can't talk and all that sort of thing.

But after this terror had succeeded, they thought, in achieving its ends, Aristide was permitted to return, but on a condition, namely the condition that he accept the program of the defeated US candidate, which is precisely the wording that was used. They said, the renovated government has to focus its policies on the needs of civil society. Primarily, that means the private sector both national and international.

So US investors are Haitian civil society, but the people in the slums and the hills aren't. And a very harsh structural adjustment program was imposed. I won't go through the details, because it's too late. But it succeeded in further devastating what was left of the economy.

And the Haitians still resisted. That's why they haven't understood what democracy is. And they'll have to come to learn this, you know. 200 years we've been trying to teach it to them. They still haven't gotten the idea. So you could understand why there's an embargo.

DORSINVILLE: Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you, Professor Chomsky, for laying the groundwork for Dr. Farmer's current analysis of the Haitian situation, economic, political in the backyard of democracy. Thank you. FARMER: Thank you. It's a real privilege to be here with all of you and the two of you. I want to thank Dinesh and the many people who organized this forum. And you used the term the uses of Haiti for tonight. And I was very grateful.

But I would add that when Noam wrote the introduction to The Uses of Haiti, he wrote, "this book is slated for oblivion." And I want to thank you for that, Noam. That was very helpful as a marketing ploy.

[LAUGHTER]

And, of course, as ever, he is correct. I just came from the hospital, and I was rounding. And I was seeing a patient. I was late. And I said, I got to go. I'm giving a talk with Noam Chomsky.

One of the people on my team, by the way, said, why can't he come round with us, you know? But the other person said, why are you guys talking together, I mean, you know, if you guys agree on everything? And I said, well, he's about the only American intellectual I know who's actually the telling the truth about what's going on in Haiti.

And I wish I could make a long list. And maybe I'm missing some things. I suspect that I am. But, you know, I think that in the 20 years that I've been working there-- can we make that obedient to my every whim here, that thing?

[LAUGHTER]

In the 20 years that I've been working there, I think that a lack of forthright analysis has never been so wanting. And I'm a physician and mostly do medical work. But I feel compelled to make up something as he fixes the slide machine, anyway.

[LAUGHTER]

Could you tell? This is going to sound great on radio as slide presentations always do.

[LAUGHTER]

You probably, you know, made this not work. On, off maybe?

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

Yeah. It's not real remote. There we go. Is it on?

AUDIENCE: Yeah.

AUDIENCE: It's on now.

FARMER: Nancy, don't take away from my time. That was their fault.

[LAUGHTER]

No matter how you look at Haiti-- and I look at it as a physician does-- the situation is grave. And I'll spend a fair amount of time talking about what's going on now. And I will not spend a fair amount of time going over the statistics.

I'll be glad to share them with any of you from the sources that we think are fairly reliable. But life expectancy has dropped in Haiti over the past few years. People don't have access to clean water.

Births are not attended. It's very dangerous to have a child in Haiti. In one study, for every 100,000 children who were born alive, 1,400 women died in childbirth, the highest by far in the hemisphere, one of the highest in the world.

And so as someone who works with many others who are providing health care services to people living in rural Haiti, in one of the poorer parts of Haiti, which is saying a lot, we need to be concerned and engaged in understanding what is driving forward this really wall of pathology. And I'm, of course, thinking about pathology in terms of individual patient's illness. But the pathology, as Noam has said, is social in origin and is transnational in origin and is historically rooted in a series of processes that, unfortunately, for many of our commentators did happen more than 5 minutes ago.

And so understanding what's happening now means that we have to understand what has happened in the past. The decline of the Haitian economy in recent years has been severe. It's been, you know, one of the most striking trends in Latin America.

This is from the United Nations Development Program, a what I've called here economic devolution, shows the negative growth rates of the economy. And there are many ways of looking at misery. I do have to wonder who puts together things like the human suffering index. It's not really what I would like to do as a pastime.

But when something called the human suffering index was put together and first published not too long ago, Haiti was the only country in the hemisphere that figured in the top five. It was number three. And the only two other countries ahead of it were both in the middle of a civil war.

And in reflecting on this datum, of Haiti ranking number three in terms of human suffering, you know, you came to think about the conditions there as a sort of war. And it's a war of the rich against the poor, basically. And the rich, of course, are sitting in many different places, not so much in Haiti right now. But they're there, too, and waging a sort of war.

And a patient who I saw in the clinic said, it's like a war here every day the fight for food, and wood, and water. And that's what the situation is reduced to in Haiti, every day the fight for food, and wood, and water-- wood, of course, to cook the food. So Haiti has become-- and this is from The Economist, "the nightmare next door."

And it's very important to find out why. And you should look back at the characters of the American occupation during that time, the characters not of the American occupation, but really in the American press at the time of the occupation of Haiti, which were very similar to the one I just showed you. Now, back to this question of more than 5 minutes ago, this was a comment made by John le Carré the English novelist, who wrote in The Nation about "A War We Cannot Win."

And Noam already said it. "Suggesting that there is a historical context for the recent atrocities is by implication to make excuses for them. Anyone who is with us doesn't do that--" doesn't do historical analysis. "Anyone who does is against us."

And he's referring very specifically to, he was referring this essay to, discussions about what happened here on September 11th. Noam used another expression, that those with their boot on the neck don't want people who have their neck constrained in that manner to be asking questions about history or making comments. And I'm going to do just that in talking about echoing many of the things they've already said, but I want to add a couple to that.

And I can speed through this part, because Noam went through it already. The first European settlement in the New World was in Haiti. And that's where, in fact, one of those three ships-- I can't remember which one. I'm sorry. Noam will, of course, know-- foundered off the coast of Haiti in 1492. And part of the wreckage was used to make one of the first European settlements in the new world.

And the fact that as many as 8 million people could have lived on that island then in 1492 is just an astounding and horrific thought. And that figure of 8 million comes from demographers at the University of California who are using mathematical models to try and figure out how densely populated the country was in 1492, an astounding and terrible series of events. But has already been mentioned, if the Indians wouldn't do as slaves, then we needed more hardy slaves.

And this is actually the subject of great interest in Haitian scholarship and history, was the change from using indigenous slaves to kidnapping people in Western Africa. Just as a couple of asides to give an idea about the scale of what it took to make Haiti the most profitable colony in the world, in European history probably, it took up to 29,000 slaves a year as imports. So Haiti was, in fact, the number one destination in the New World for slaves.

It was ahead of Cuba and far ahead of the other islands around there ahead of the American South. And, in fact, that fact, 29,000, was at the peak. And that demographic fact is one of the reasons that led to the Haitian revolution is that there were just so many slaves compared to slave masters that the numbers were eventually on the side of the enslaved who staged a series of revolts throughout the New World. But only one of them was really successful, the Haitian Rebellion, in terms of leading to, you know, victory to the slaves.

And from 1697 on, it was the French who were the slave masters. And they replaced, over the ensuing century, the Spanish and made Haiti into a really earnest producer of tropical produce, coffee. By the way, please don't be knocking soft drugs-- coffee, sugar, cotton, indigo, other things that couldn't be grown in Europe. And Haiti was, as has been mentioned, providing about 2/3 of all European tropical produce by the time of the French Revolution-- excuse me, the French "Revolution--" got to get that right.

And I think the Haitians would be in agreement, the Haitians here tonight. I know the Haitians in Haiti are in agreement that none of these revolutions in Europe were really serious. As the Haitians would say, they weren't serious. Because any serious revolution would, of course, liberate the slaves.

When the slave owning mulattoes was went to France to speak in front of the national parliament in France, the so-called Revolutionary Parliament, they went to argue for the right of mulattoes to own slaves. So, again, I have to ask how resonant is that performance of the first Haitian elite with their performance in the ensuing 200 years.

I'll just say it right now. I work in rural Haiti with people who call themselves peasants and who have very much slanted, if you will, towards truth in my view, the way that I see this. But that was one of the first gambits of the emerging Haitian elite who owned slaves was to have the French recognize their right to own slaves.

So the real Haitians, the slaves who revolted, were also leading a revolt against the mulatto elite who wanted to continue owning slaves. And, of course, not all the mulattoes-- and this term by the way, is from colonial times. And, of course, it's a social construct. I'm just using the terms that are used inside Haiti.

But there was about 28,000 French living in Haiti, about maybe 40,000 so-called mulattoes mixed of French and African descent, and about half a million adult slaves. And so there were also children. And the adults slaves were men and women working and counted as slaves.

And, in fact, the French kept rather meticulous records of the colony. And so we have a lot of, you know, information about what life was like during the slavery and during the colony. And I'll just go through some of that.

I mentioned already that the size and scope of this little factory, which is the size of the state of Maryland, was just churning out wealth. Noam mentioned that many French cities owed their wealth. The cities of Bordeaux, for example-- which, if you've seen, is a beautiful city-- was virtually built out of this money.

And all of the big coastal cities of France came from this trade. They were built up during the slave trade. And, in fact, the same buildings that are there now that everyone admires as so beautiful were really the fruits of this Triangular Trade.

The impact, of course, in Haiti on the lives of these slaves was terrible-- one in three slaves dying within the first three years of life in Haiti, in the colony. Haiti, by the way, was the name of the colony before the Europeans came. It's a local word.

It means high country, mountainous country. It was the indigenous term. And it was taken back by the leaders of the Haitian revolution after the Europeans were defeated.

Now, this is from a Haitian who was a slave during before the revolution, then was one of the few people writing, you know. Of course, in the United States, we really don't have a lot of testimonies from slaves, narratives from slaves. And it's a very interesting area of historical scholarship.

But in Haiti, there actually are. Because after the revolution, many people wrote about their experience. And I won't read this to you here. You can read it. But I know that it says, "have they not--" and then lists the crimes against the slaves that the French perpetrated.

Now, the revolution began in 1791-- as Noam said, the only real revolution in the 18th century-- and went on for a decade and more. And one of the amazing things about the revolution was that Haiti was considered so important to the French economy-- again, like Bangladesh, now considered the international basket case of the hemisphere-- that the largest European armada ever to set forth from Europe since or before left France under Napoleon's direction to retake Haiti. 80,000 French troops and also conscripts from Poland and other places that the democratically-minded Napoleon was taking over in Europe, 80,000 troops-- 40,000 Navy and 40,000 ground troops-- went to Haiti, which, again, even to this day is just astounding to think of that sort of movement of troops across the Atlantic.

And he sent his brother-in-law, General Leclerc, who was married to Pauline Bonaparte, who died in Haiti, in northern Haiti, never returned. Pauline Bonaparte also lived there. And this was, again, at a horrible cost to the Haitian people. They started calling themselves Haitians during the revolution, during the war.

And when I say horrible cost, the General Leclerc wrote a letter back to his brother-in-law at one point saying, we can never retake this colony unless we kill every single man or woman who has carried epaulettes, meaning the slaves who are now in the army which is being led by the leaders of the slave revolt, and every child above the age of 13 who has done so as well. This is in the correspondence between General Leclerc and Napoleon shortly before he died. So he already was sending messages back home that this was not going to work, that they were going to fail unless they had a campaign to wipe out all of the adults. And by adults-- as he said, 13 years and over.

Now, what happened after the revolution has already been commented on here. The revolution ended in the battle I just showed you, the Battle of Vertieres in November of 1803. And on January 1st, the Haitians declared independence, the first independent nation in Latin America.

They took the French tricolor and ripped out the white part and, of course, saying we're getting rid of the whites. And the Haitian flag was initially the red and blue bicolor that was recently restored. And in that year, they declared Haiti a safe haven for any indigenous person and any escaped slave in the New World.

So that was another part of these unprogressive features of their constitution. Noam mentioned, also, that it said no European, no foreigner, will ever set foot in this country as a landowner. And that was part of Dessalines' constitution of 1804.

And Dessalines, as you might imagine, is regarded as the father of Haitian independence by the Haitians and regarded as a butcher by the Americans and their friends in Europe. Now, how does this work itself out? Nancy used the word trade embargo.

But, actually, what we usually do with Haiti is not a trade embargo. And you clarified that by saying unfavorable conditions for the Haitians and very favorable conditions for the Europeans and Americans. But it's not a trade embargo. It was worse. It was a refusal to recognize Haiti's independence as a state.

And as has already been said, this went on till in 1862 and this is just stuff from, again, the US official congressional record. You know, Noam gave me advice years ago. He said, if you're going to write books like that one, try to use formal US official sources.

And I followed that over the years. It's a great source, I mean, of information about our policy. And this is 1824, a senator from South Carolina. Since this is being taped, I'll read it.

"Our policy with regard to Haiti-- Hay-ti-- is plain. We can never acknowledge her independence. The peace and safety of a large portion of our union forbids us even to discuss it."

And this was the standard fare inside the great halls of democratic United States during those years, those decades, in which we were exploiting relations to Haiti, but not recognizing. Here's the kicker to me. And this was mentioned, too.

The Haitians, of course, still were growing tropical produce after the abolition slavery. However, they were doing it with free people, peasants mostly. And coffee is something you don't need to grow on plantations.

You can grow on small plots of land, on hillsides. And it replaced sugar and cotton as the main exports of Haiti, because peasants could grow it without working on plantations. And I can promise you that the Haitian peasantry has never wanted to work on plantations.

I mean, I can't imagine why not. The conditions had been so pleasant before. So it's been a long struggle. The land reform struggle in Haiti is very interesting and very poignant. But the bottom line is most of the Haitian people refused to work under anything that looked like plantation conditions, and so were exporting coffee more than any other crop.

But the amazing and, you know, horrible thing is that when people talk about reparations now-- and Nancy mentioned the Durban Declaration-- the Haitians already paid reparations to the slave owners. And the size of the payment was astounding, 150 million francs. And according to a fairly sober late 19th century Haitian historian, early 20th century, who looked at this, you know, in retrospect just aghast, he said that, from a relatively balanced economy prior to the payment of this massive debt to the French, this led to a major disruption that really continued to have its impact on the Haitian economy throughout the rest of the 19th century, this payment of debt.

And the French at this time were also dominating Haitian trade. And that went on along with struggles from the British and the Germans. And some of you might not know that at one point in late 18th, 19th century, the Germans-- and I believe was under Kaiser. Because Kaiser sent some very lovely envoys to Haiti, one of whom took the Haitian flag and smeared excrement on it in the Bay of Port-au-Prince, the military envoy of the Kaiser of Germany. That was the way that the civilized societies of Europe chose to mark their respect for Haiti.

And this went on for some decades. Europe, France, Britain-- I mean, sorry-- France, Germany, and Britain vying with the United States for influence. But by the end of the century, there was really no competition. Although, when the Americans sent in the Marines in 1915, they claimed one reason was to limit German influence in Haiti, which had already been virtually erased in the previous two decades.

So when the Marines went in, then began the intensified series of events and processes of development and scientific development that have made Haiti the paradise that it is today. I would just add that the modern Haitian army was created by an act of Congress, US Congress, and signed into existence in Washington. And I'm going to soon switch to a sort of local analysis. But when I talk about the valley in which we've been working for a long time, you'll see very similar kinds of events that are really transnational.

I mean, the modern Haitian army-- how often do we acknowledge that, you know, the army that we suddenly declared a rogue army after, you know, really uncompromising and ongoing support for many decades, was really created by the American occupiers-- not just trained, but created? And then in came the agribusiness and missionaries of the early part of the last century, 20th century. And the kind of appropriations of land that Noam mentioned in his talk, these were usually with these sort of partnerships with the Haitian elites, so that there would be Haitian elite ownership, meaning wealthy people in Haiti, and US ownership of, you know, a plantation.

Noam mentioned rubber. But during the World War II, Haiti also began growing sisal hemp-- or sy-sal hemp-- in order to make big ropes for the ships. This is before nylon replaced those. Haiti was suddenly the world's leading producer of hemp, because they could flip the switches on these plantations-- rubber, hemp, whatever was necessary locally. I'm kidding. Because, of course, I don't know that hemp has many utilities locally. I guess you can make baskets or things out of it.

Now, what can we read in that great journal, the national journal of record The New York Times? It's already been quoted today. Instability was the pretext reducing European, German, influence during the war. The Convention haitiano-améicaine-- spelled wrong, sorry-- basically, it gave the United States complete administrative control of Haiti including the ability, as was mentioned, to rewrite the Constitution to remove those very unproductive features of the Haitian Constitution.

And the troops stayed in Haiti until 1934. And you already heard about the resistance. The Haitian people gave spirited resistance to the occupation. And that resistance was based among the peasantry.

In the very place where I work, Central Haiti, Central Plateau, that's where the resistance was based. It did not come from the Haitian elite. Although, there were some intellectuals who opposed the American operation in their own somewhat timorous way compared to the peasantry, who really opposed it.

The occupation of Haiti led to the restoration of forced labor crews, [FRENCH]. The major roads built during that time were built largely with forced labor. There's grotesque documentation of this available in the historical record. And it was very interesting to see how it gets sanitized and retold in the non-Haitian accounting of this. But the Haitian accountings had the added advantage of being correct.

[LAUGHTER]

Now, this led rather seamlessly, in fact, to the Duvalier family dictatorship. That is no one could come to power in Haiti without the benediction of the US government from the time of the occupation, of course, when it was overt and formal. But from 1934 till 1990, that was really the prerequisite for coming to power was to have US backing, you know, from the US ambassador and from the latest whatever USAID might be called on that particular day or the other US institutions.

And so forth Francois Duvalier, you know, again, I think there's a lot of confusion about this. Francois Duvalier was supported by the American embassy in Haiti in 1957. He received the report of the embassy. Because you read a lot about the United States spirited resistance to the Duvalier dictatorship, you know of course, not in Haiti, but in the United States.

But it was pretty unremitting, our support for the Duvalier dictatorship. There were a couple of years where the activities of the dictatorship were so terrible. I mean, just to give an example, which, again, seems to have escaped everybody's mind when they're talking about the reign of terror that exists now-- I mean, Francois Duvalier would have someone killed and then display the body across from the airport for, you know, days.

So that's not very subtle symbolism according to anthropologists with whom I work. And this was, again, obviously meant to draw attention to the fact that the dictatorship would tolerate any sort of challenge to its power. Every single independent press, radio, newspaper, the few independent-minded intellectuals that may have theoretically existed at that time, they left or were killed.

And it took about, you know, 10 years to really shut down any sort of threat from the military, from the army, which had been previously the primary determinant of who would come to power, the United States and the Haitian military-- not that those two institutions had any relation, of course. And so Francois Duvalier undermined the army and the opposition, silenced the opposition very completely, and spent the rest of his very long reign-- he used to say [SPEAKING FRENCH]. I'm going from the palace to the cemetery, you know? And he did. He was there until he died.

And then his 19-year-old son, who, from what I understand, had never left Haiti, became president of the oldest Republica in Latin America-- 19-year-old son who had, you know, of course, an advanced degree from The Fletcher School. Anyway-- I'm kidding. That was a joke. Well, anyway, I better be good. I'm on tape. Sorry.

[LAUGHTER]

Now, 1971 that happened. And the years from '71 to '86 were years of decline for reasons that are acknowledged. And there were really thousands of refugees. You heard about the welcome they got from us, a really amazingly repugnant policy, actually. The seizing and interception of refugee ships on the high seas and then the return of refugees is, again, in violation of many treaties to which the United States is a formal signatory. Is that [INAUDIBLE], signatory?

But it didn't bother us too much. And then there was political unrest that began in '85 and was very much associated with a popular movement. That is a movement based, as has been mentioned, among the rural poor and the urban poor in slums.

And it was an amazing thing to be living in Haiti at that time and be working there. Because I had never seen anything like that in my experience as an American. There was so much popular support for the popular movement that virtually every member, every person who lived in the village where I was living and working, am living and working, everyone was part of the popular movement without any exception.

And in 1990 when, at the last minute, Aristide announced his candidature, you know, you could practically hear the stampede of people going to register to vote. Because after what happened in 1987, which is unstinting support from the United States government for the Haitian military-- and here's just a number for you. Over $200 million in aid passed through the hands of the military junta.

I actually am going to risk saying this on tape. I spoke with someone today in a prominent US office with the fate of Haiti in its hands. I will just say that. And he was saying, well, you know, I would really like to see the frozen aid released.

What we need to do is get the government to, you know, promise to use the aid in an open and clear manner and be subject to various forms of scrutiny, et cetera. And I couldn't resist. I couldn't stop myself.

I knew I just sort of said nothing. I was standing in the ICU unit in the surgical ICU, you know, with a phone and trying to write a note about a patient, listening to this guy, knowing that, you know, I didn't have to listen the whole time. But I said to him, well, you know, I've been working in Haiti 20 years.

And, you know, during the dictatorship, there was never any sort of real scrutiny of USAID and during the military juntas. Why now? And then he just said, you're right. I really don't understand US foreign policy.

I did not say I'm going to give a talk with Noam Chomsky. I just said, I've got to get back to seeing patients. And I'll call you tomorrow.

Now, you already heard that we trained a lot of those very delightful military officers who held sway during these times. I'm going to skip ahead to what happened in 1987 and skip through some of the stuff where we were.

But in 1987, there was a massacre of voters at the polling place. Now, again, that's more than 5 minutes ago, so everyone's forgotten. But can you imagine?

I was there in Haiti that day. And can you imagine seeing groups of people lined up to vote and then, you know, seeing them taken out at the polls? I mean, this was really incredible.

And, of course, in the middle of the reign of a military junta-- I mean, granted it is rather far-fetched to suggest that the military may have had something to do with this. But it was pretty clear to the Haitians that this was basically the action of the Haitian army, which has had no non-Haitian enemies, you know, in hundreds of years. Only Haitians have been the enemies of the Haitian army.

And so a lot of Haitians were not going to vote in 1990 until Aristide registered. And then it was something like a million people registered in the last two days. And so, you know, experience that, to see that happen and to experience that, was really very eye opening for me.

In the village, you know, where we work, there was this one woman who's a good friend of mine who's what we used to call when I was growing up a lunch lady. She makes lunch in the school cafeteria. And she was and remains, as do most of them, a very devout Aristide supporter.

And I told her that I had been listening to the radio. And I heard a poll from Port-au-Prince. And she said, what's a poll? And I said, well, that's when people go out on the street and ask people how they're going to vote.

And she said, what did it show? And I said, that Aristide would win over 50% of the vote in the first elections without a runoff. And she said, well, that can't be true.

And I said, I thought you were a big Aristide supporter. And she said, oh yeah, he'll win 99% of the vote if it's a re-election. And so she thought that was unlikely, that even though there were 11 candidates, that he would win with only a plurality in the first round with 50-something.

And, in fact, he did win with a much higher plurality in the first election. There were never any runoffs. I mean, now, granted, we always have very clear outcomes in our elections as well and that runoffs are not necessary. But, you know, it was still a learning experience for me even though, you know, I'm American, so therefore democratic by training.

Now, in the interest of skipping ahead, I'm going to just close by talking about health conditions in Haiti. Because it's important. And I think everybody here should know about this.

The health situation in Haiti is dire by any kind of criteria. And this is an image-- not an image-- a picture of a girl with typhoid fever, which along with tuberculosis and other what the Haitians call stupid diseases, actually, are the primary determinants of life and death in Haiti. So, of course, one of the first things to do is to have a public health system that takes on these problems.

By the way, I couldn't resist putting this image here. This is a child with anthrax. And, you know, it must be because Haiti is a terrorist state that they, you know, have anthrax there.

That was actually brought up in the American press. And, you know, Haiti has real anthrax, meaning the kind that's zoonosis, contact with animals. In the case of this girl, she has anthrax of the face. It was a goat.

And someone died of anthrax in this outbreak. She came in with another, an adult. And they got treated and did fine, as one does. But someone died in their village.

Anyway, someone mentioned in the American press that Haiti could be a terrorist state manufacturing anthrax. And a Haitian veterinarian said, that's just ridiculous. And, well, you can't respond to every one of these nut-so suggestions.

And I had this image in my mind of, you know, a group of Haitian goats getting together and say, let's get a lab going and get some of this stuff off of our fur.

[LAUGHTER]

Anyway, now, I told you about election day 1987. And I mean, this is inside a school, you know. And it's just awful what happened.

And so the willingness to participate in this election of 1990 was really a strong statement about commitment to democracy. And so I mentioned what happened already. But after seven months, there was a violent military coup.

And you know this. And it's already been discussed by Noam, which led to the deaths of really thousands of people and massive internal migration in addition to external migration. Internal migration, because we were working in rural Haiti.

And people fled from the slums out to where we work. And so we saw, you know, enormous changes. And it was just a huge and ongoing disruption for a long time.

And as Noam said, it was very frightening and not theoretically. I mean, I personally know a number of people who were killed during that time, including a Haitian businessman, one of the only ones to say, well, you know, the popular movement is probably a good thing, since it includes about 90% of the Haitian population. And his brother was murdered in downtown Port-au-Prince.

And during a memorial mass for his brother, he was shot in the head and killed during mass by paramilitary forces. And this is the level. And this is a prominent businessman who, you know, was very wealthy actually, who made the mistake of not doing what business people in Haiti are supposed to do and saying, you know, these savages from the hills and slums really cannot play a role in the future of Haiti.

And then, again, the embargo has already been discussed, the fake embargo. Now, we have a real embargo, mind you. But the fake one-- I mean, I, again, am sitting in Haiti reading The New York Times and thinking, what on Earth are they talking about?

My mother's a librarian. And so she was, you know, sending me things. This was when we had an office in Port-au-Prince, before we had to close it down during those years, because of death threats and intimidation.

We finally just closed up our operation in Port-au-Prince completely. But she was sending me these things. And I'd say, this is just not at all what's happening. But the image that comes to mind is, you know, we were able to detect refugees in boats from, you know, miles away with radar. But an oil tanker steaming from Texas to Port-au-Prince didn't show up on the radar. So, I mean, granted they're small boats and all, those tankers.

So fine-tuning-- I remember that was Barbara Crossette, wasn't it, who wrote that fine-tuning the embargo? That was The New York Times. She probably won a million awards, Pulitzer and things like that.

And Noam has already covered the fake embargo. So I'm going to go ahead and turn to the real embargo. Now, here's where we end up after, as Nancy said, use the term impoverishment. Because it implies a historical process.

It takes a long time to impoverish a place. But here's where we end up, you know, with, again, the most impoverished country in the hemisphere, which, of course, only coincidentally is the country most linked to the United States for the longest time. I mean, that's surely just a erroneous association.

And the part that I see and concerns me just in terms of everyday practice as a physician is that the impact of this on health is, of course, profound. And so most of the patients we see have the diseases that poverty engenders and sustains. And they can be prevented and treated at the end, you know, distally as we say in medicine.

And that's what I do. I'm sorry. I mean, it's kind of what I was trained to do is to sort of get people when it's too late. But the real responses to this will be, of course, determined, in my view, outside of rural Haiti.

This is the receiving end. This is not the determining end. I mean, the numbers are terrible. Well, here, let me just give you this one example to close my comments.

So what would a public health infrastructure do in Haiti? What would a government do if, instead of being interested in, you know, imprisoning and arresting, what if it really wanted to promote health? Well, it would have to have capital. They'd have to have funds.

You can't do public health with no money. You know, if you knew the money that gets spent in Massachusetts on public health, I was astounded when I saw the numbers. It's something like more of all China and India in just our little tiny state of 6 million people.

And it's good. Hey, we like this. You want to, you know, have huge investment in things, why not choose public health rather than, you know, bombers and things like that? I'm all for it. Sign me up.

However, you can't do it with no money. You have to have money. So, not coincidentally, Haiti, of course, was completely broke just like it was at the end of the revolution. Everything had been burned down and destroyed.

In fact, it may be worse now than then, because some parts of Haiti were not burned down. And the soil was still fertile. And deforestation had not done what has done now.

But a government, should it want to do this, would have the Ministry of Health put together with consultation, which they did-- I don't like this word health reform, okay? But reorganization was an inoffensive one. I had nothing to do with this.

I went and found this. It's a matter of public record. It was very easy to get from the Haitian authorities, by the way, and a little bit more difficult to get out of the Inter-American Development Bank authorities.

But on July 21, 1998, the Haitian government and the Inter-American Development Bank, which is a very important institution in Latin America. With a couple of notable exceptions, all of these officialdom countries go through these mechanisms. And they signed a loan for $22.5 million, which is a huge amount for the Haitian Ministry of Health.

By the way, in that anthrax outbreak-- I think it was the anthrax outbreak. It may have been an outbreak of meningococcal meningitis. I sent an email from central Haiti to a friend of mine who was with the Ministry of Health saying, you know-- it was meningococcal meningitis.

I said, we're having an outbreak of meningococcemia, meningococcal disease. And a baby had just died. And we saw another case with purpura fulminans and then saw another case the next day.

So we alerted them. And I got no answer back, because they were supposed to come out and investigate. And that's what they had asked us to do. And a couple of months later, I saw the guy who was, like I said, a friend of mine who's a very earnest, good person.

And I said, why didn't you come out to investigate this? And he said, we didn't have any gas for the Jeep. And I said, you know, that was the end of that discussion.

Because I thought, you know, I'm not going to be rebuking people for not having gas. It's like, that's sort of our foreign policy, yell at people for being poor. So, now, let's yell at the Haitian government for being poor.

We do that very well, by the way, with very little in the way of critical response from, you know, the mandarins of American foreign policy, including the intellectuals. Again, I don't know. You follow this more closely than I do. I haven't seen a lot of commentary on what it is exactly we're doing, but it looks a lot to me like yelling at the poor as really powerful, wealthy people-- nation, rather.

So this was the goal of the loan. And, you know, it's pretty standard fare, really quite dull to read, actually. I can't believe I had to have help from my co-workers getting through it. It was boring.

These are the project goals. I'm just summarizing them for you. But, basically, they were very standard public health goals, reduce infant mortality. And, you know, there was a plan. And it was approved by the Haitian government.

And it got stalled in parliament, because there was a famously obstructionist parliament. By the way, that's why the Haitians voted in March. These were the famous disputed elections.

In March of 2000-- nothing to do with the presidential elections that would happen later on that year-- the Haitians went out and tried to do clean slate for one party, so they could get rid of the obstructionist parliament. And they did. You know, everyone went out and voted for the same party in order to have the obstructionist parliament not block-- it's sort of Haitian gridlock of blocking every-- and I would say this is, by any kind of standard, a reasonable proposal and, you know, what you'd want a public health project to look like.

So in any case, then what happened? Well, in October 1998, the Haitian Minister of Health presented the project to the legislature. And I just wrote obstructionists. Because that's what they were doing.

They were basically trying to block everything that came from the central government. This was not under Aristide, by the way. This is under Préval.

And then after the March elections had led to a non-obstructionist parliament, that is a parliament that would vote to approve proposals from the central government, it was ratified there. The Inter-American Development Bank said, okay, money's on the way. This is announced in the papers as official.

And then there were new conditions put on. And this is when I started hearing about this. You know, if you're sitting there in rural Haiti and your number of patients is increased by two-fold in 18 months-- and you have seen various clinics and hospitals close down in the region.

And, you know, your doctors and nurses are saying, we can't see all these patients and it's just not possible, if there's a medical staff of eight or nine people, to see 400, 500 patients in a day. And so I'm the medical director, so they're coming to me with complaints. They say, we can't see all these patients.

And I say, what can I do? These are all Haitian colleagues. I say, you know, the country is sick. We have to see the patients. But I'm just waiting for this IDB thing to go through, so that the other institutions can be reopened, as is the stated intention of the Haitian Ministry of Health. So I'm waiting.

So I started asking. Where's that loan that would allow the other public health-- because this is a private charity hospital. That is a private hospital doing the work of the public health infrastructure.