Women of MIT: Shaping Policy in Academia and Across the Nation

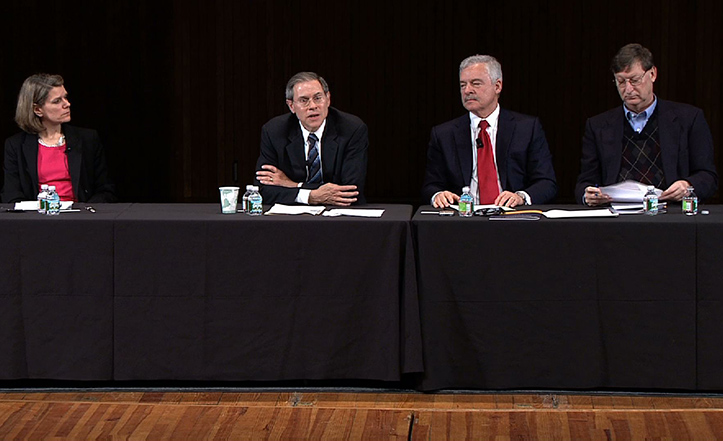

KASTNER: Welcome everyone. So in connection with this symposium, the women faculty in science and engineering carried out a new study of the status of women faculty members in those two schools. And if you've read the report, an overwhelmingly positive view of MIT emerged, with dramatic improvement since the original 1999 report. We heard a lot about that yesterday.

The positive improvements include an increase in the number of women faculty members, more equitable resource and salary distribution, and the increase of women in senior administrative positions. The vast majority of the tenured and untenured women interviewed emphasize that MIT offers outstanding opportunities and resources, and that the Institute is a much friendlier and supportive environment than perceived from the outside.

Despite these positive findings, there are still challenges. Some of these are the subjects of our panel discussion this afternoon and relate to making academic careers at MIT even more attractive so we can increase the fraction of women in our faculty even further. It's really important that we address some of these issues.

It's also likely that similar improvements will increase the racial diversity of our faculty. The organizers have asked us in this session to address several issues. One is making science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers more attractive to young women. Second, balancing the needs of young women to start families and starting academic careers. Three, eliminating harassment. Four, improving the climate for women in other ways. I guess there were four.

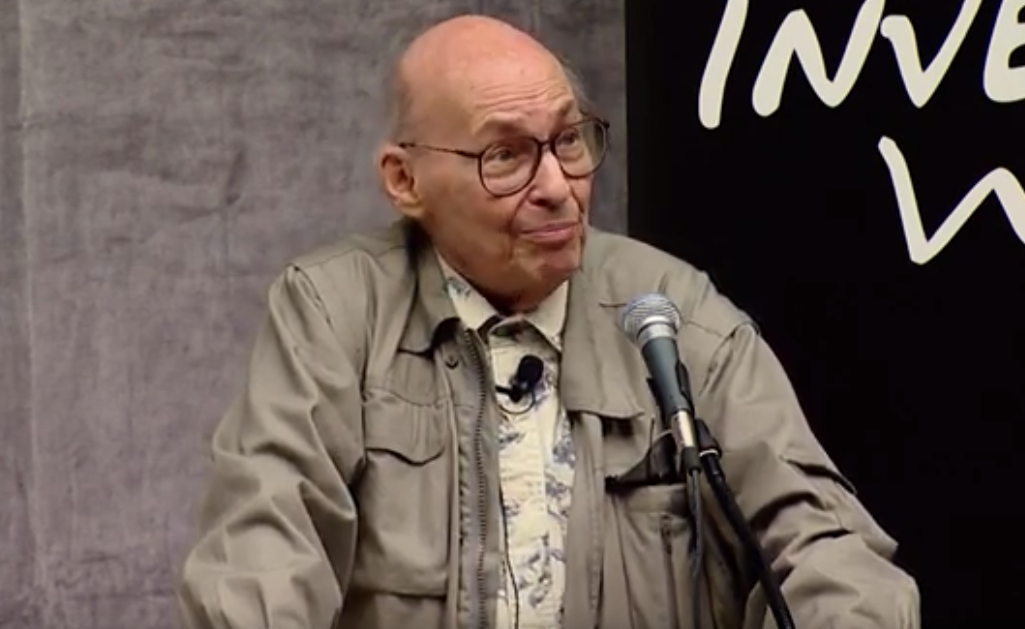

I will introduce our two three panelists and then I'll ask each of them to speak for 15 minutes on these topics. We'll then take questions from the audience. So I'm going to introduce all three of them. And then they'll speak in turn. And I'm introducing them alphabetically. And it happens that the first is a male, but I apologize for that. It's my friend Bob.

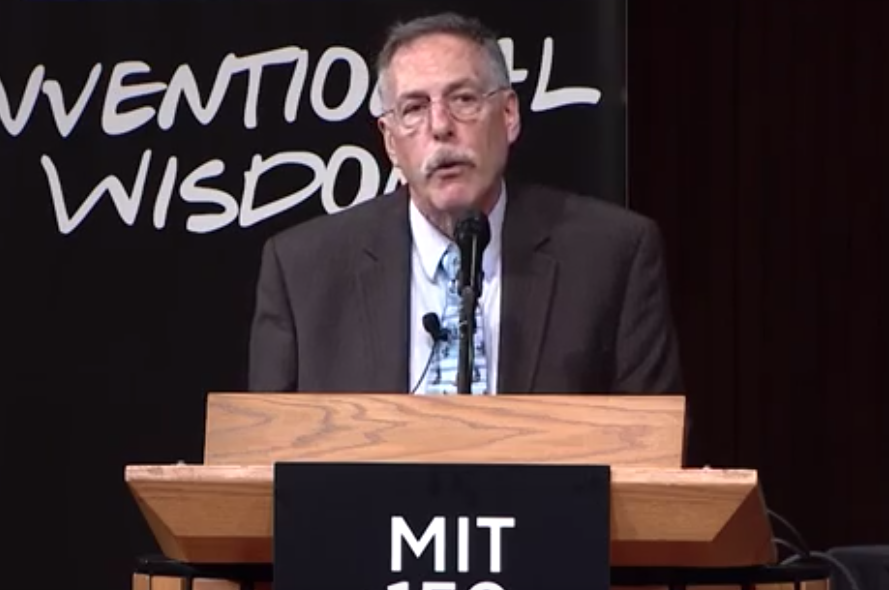

On Wikipedia it says Bob Birgeneau is a Canadian physicist, which is true. He's chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley, and prior to that he was president of the University of Toronto from 2000 to 2004.

Bob was the first of his family to finish high school. He graduated from St. Michael's College in Toronto, receiving a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics. And then he received his PhD In physics from Yale in 1966.

From 1968 to 75, he worked at AT&T Bell Laboratories, and then he joined MIT as a professor of physics. During his 25 years at MIT, he served as chair of the physics department and then as dean of science. Birgeneau's research accomplishments have had great impact, and he has been honored for them in many ways. He's a fellow of the US National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society of London, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. Among the awards he has received for his research on the fundamental properties of materials is the Oliver E. Buckley prize of the American Physical Society.

Throughout his career, Birgeneau has been a passionate advocate for increasing diversity in academia. In 2008, he received the Carnegie Corporation academic leadership award for championing excellence and diversity in education. Most recently, he was one of three recipients of the Shinnyo-en Foundation's 2009 Pathfinder's to Peace Prize for his, quote, "commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and to the integration of public service as an essential component of the academic experience."

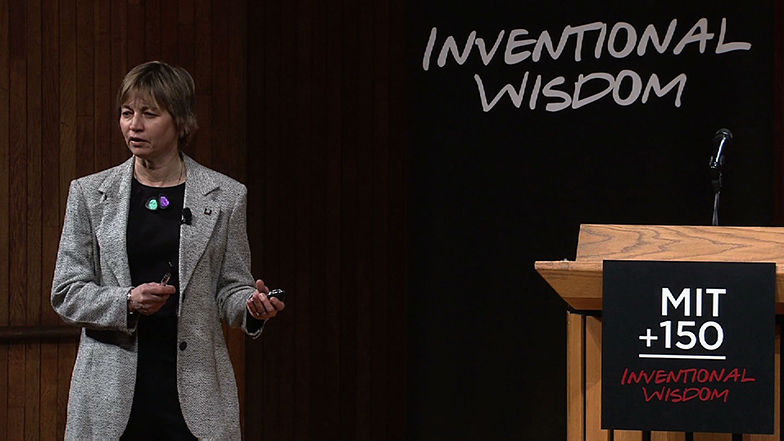

Our second panelist is Dr. Heidi Hammel, who is the Executive Vice President of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, called AURA. It operates world class astronomical observatories. Dr. Hammel is also an interdisciplinary scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope. Her primary scientific research focuses on astronomical observations of planetary atmospheres. Dr. Hammel also does a significant amount of award winning education and public outreach work. In her spare time she's a single mother of three school aged children.

Hammel received her undergraduate degree from MIT in 1982 and her PhD from the University of Hawaii in 1988. After a postdoc at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, she returned to MIT where she spent nearly nine years as a principal research scientist in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences. In 1999 she joined the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado as senior research scientist, and eventually codirector of research. Her position at AURA began in 2011.

Lisa Maatz is Director of Public Policy and Government Relations at AAUW, the American Association of University Women, which started as the Association of Collegiate Alumni founded in 1882. Ellen Swallow Richards, MIT's first female graduate, was one of the cofounders, and MIT was one of two charter members.

As AAUW's top policy adviser, Lisa Maatz works to advance AAUW's priority issues in Washington. Maatz provides leadership to several coalitions working to advance opportunities for women and girls. Recently featured in the book Secrets of Powerful Women Maatz has developed a reputation for her strategic approach to legislation and advocacy. She has done similar work for the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund and the Older Women's League, and was a legislative aide to US representative Carolyn Maloney.

Her grassroots advocacy career began when she was the executive director of Turning Point, a battered women's program recognized for excellence by the Ohio Supreme Court. Maatz is a graduate of Ohio University, has two masters degrees from Ohio State University. She holds an adjunct appointment with the Women in Politics Instituted at American University. Her honors include the women's information network's Young Woman of Achievement Award, and the Mentor Award from the Public Leadership Education Network. Maatz was also a congressional fellow for the Women's Research and Education Institute, and has received a mayoral appointment to the Washington, DC Commission on Women.

I think my first slide, my only slide-- if there is a slide-- well, it just repeats the topics that were supposed to be the topics of discussion today. So let's move along, and I'll ask Bob Birgeneau to speak first.

[APPLAUSE]

KASTNER: Thank you so much Marc. And it's just such a privilege to be back here at MIT and to see so many old friends and to even gotten the chance to make some new friends. Why is this not advancing?

So I thought I would really, just as a foil-- and I apologize coming from Berkeley, but since I'm chancellor of Berkeley, the situation I'm most familiar with is, of course, UC Berkeley. So I thought just as a foil I would show you some data from Berkeley, discuss what we're doing at Berkeley to try and address the issues, which have been the subject of this meeting for the last day and a half.

But then I want to move on. I will try and very quickly move on from challenges that women face in science and engineering to challenges that underrepresented groups face more generally, and where we're making progress and where we're not making progress, and tell you a few of the things that we're doing at Berkeley, some of which MIT might emulate.

So if we look at the number of women faculty at Berkeley as a function of time, you can see progress is slow, but it is sure. And so over the last decade and a half, we've gradually increased the number of women faculty while keeping the overall size of the faculty constant so that women now constitute just under, for 2010 to '11, just under 30% of the faculty at UC Berkeley.

Probably the single most important thing we've done at Berkeley-- and I know similar things have happened here at MIT as well-- is the full recognition for all of our faculty-- male, female, same sex couples, different sex couples-- of the importance of having family friendly policies for our faculty. And we've had two of our faculty members, the former dean of graduate school, Mary Ann Mason, and then a second professor of chemistry, Angela Stacy, who have really been forefront thinkers on this.

And so among our family friendly policies, first of all, importantly we have active service modified duties. And so every couple with a newborn or an adopted child have modified service, which means they're excused from teaching and committee duty for one semester. And for birth mothers, they're granted as an entitlement a second semester of relief of duty. So the faculty keep their research active, but their duties are absolutely minimized. As soon as a faculty member elects, as an entitlement for active service modified duties, one year delay-- not delay, but extension of the tenure clock is automatically implemented. So the person does not have to request it. That turns out to be extremely important. And the faculty member may or may not choose to take advantage of that. But it's a right. That's consistent with tenure clock stoppage.

Something we've introduced just in the last few years, which has turned her to have an inordinately positive impact, is our vice provost faculty created what he called CALcierge, which is just a play on Cal. It's really concierge-- which is a person whose full time job is to help families relocate to Berkeley and the Bay Area. And that person turns out to be tremendously effective, first of all in helping spouses find a job, helping people locate housing, helping the family locate daycare, et cetera, et cetera. So that cost of one person in their office has turned out to have a tremendously positive impact and minimized the burden for people moving.

Finally-- and I think this is true here at MIT also-- we've introduced emergency backup care, which is a phenomenal hit with junior faculty. And we've now generalized it so any faculty member can avail themselves of it, which is that if a parent is sick, if your child is sick, or even if you're writing a proposal and you just can't take care of your children during the days you're trying to write a proposal, then this service automatically provides child care or parent care for you at a nominal cost. And this turns out to be a remarkably inexpensive investment. So it turns out all of these have really had a tremendously positive impact on our faculty, but, most especially women faculty.

This has manifest itself. So how do you measure this? Well, one way that it's manifest itself, which I think is really quite dramatic is, in 2003, before we introduced all of these various family friendly processes, at that time, 2/3 of our junior faculty had no children. Since introducing these, if you now look at the make up our faculty-- this is both male and female faculty members-- 39% have no children, but the remaining 61% have either one, two, three, or more children. So this is an incredibly dramatic change.

And if I now just focus on women faculty and how that has changed between 2003 and 2009, one of the dramatic results in the study in the middle '90s was how few women faculty felt that they could take the risk of having children as a junior faculty member, because they felt there was so much cultural bias against women having children as junior faculty members.

So now at Cal, because of these change in policies, fully 2/3 of our women junior faculty have families. And again, bearing between one, two, and three children. And so our women faculty are able-- and male faculty too, but women faculty in particular are able to experience a full family life, and simultaneously be able to pursue their careers, get tenure, et cetera, effectively.

So that's all I'm going to say about issues that are specific to women in academia. Clearly there's still lots of things that we can do. But one of the things we've really learned at Berkeley is many small things which make life easier for people, and remove the typical barriers, have an incredibly important effect on women in their careers, and their satisfaction. So when you do satisfaction surveys, the satisfaction level of our junior faculty, male and female, is incredibly high.

I forgot to mention, one of the other things, but here we have the advantage of having both a large psychology department and a school of education is that we also have very robust daycare. We reserve 80 slots for faculty. We have eight daycare centers on campus. And these are also, frankly, also run as sort of educational centers, because we have a number of faculty whose specialty is in preschool education. And therefore that turns out to create an incredibly positive environment. The only challenge is the cost, frankly. And so that's an unsolved problem.

It is solved for our women graduate students and undergraduates where there's will we invest a huge amount of money in support of our women graduate and undergraduate students for child support. So that's also turned out to be extraordinarily beneficial.

So I'd like to now switch to the more general challenges that we face in academia for underrepresented minorities where it's a less salubrious story I'm afraid. So if we look at the Berkeley data and we say how has the number of underrepresented minorities evolved as a function of time-- and this is something where we've put in a lot energy, with only partial success. So this shows you the number of underrepresented minority faculty as a whole. This is out of 1,500 faculty at Berkeley. And there's now about 120. There's a recent rise in the last several years because we've been working really hard on that. But the situation for Asian Americans is rather more positive. And you so there's been a really rapid rise within the past decade actually in the number of Asian American faculty members at Berkeley.

However if we look at underrepresented minorities specifically, then you can see an interesting trend here. Sadly, at Berkeley over the last 20 years, the number of African American faculty has stayed flat at about 40, in spite of a lot of energy that we've put into this. Recently, because of some concerted effort-- and this is particularly relevant in California-- we've seen a dramatic increase in the number of Chicano Latina faculty at Berkeley. So in that way we are making some progress.

But this is an unrelenting challenge for us. And obviously we're hoping that the family friendly policies which are turning out to be very successful for women in academia will be equally successful in making life easier for our underrepresented minority faculty.

And now I want to switch to a purely academic subject. So shortly after I arrived at Berkeley as chancellor, several faculty appeared in my office. Actually, many different faculty with special interest appeared in my office. But there's one that caught my attention, the same Angie Stacy, the one who I mentioned already, the chemistry professor who's been so effective in terms of policies for women in academia, and then an astrophysicist, and African American by the name of Gibor Basri, a very distinguished African American. Appeared in my office and said, we're in California. California is, excluding Hawaii, the first state where there is no majority population. But our academic programs don't reflect that fact.

And specifically they argued, California's a living laboratory, and that, even though one was a chemist and one was an astrophysicist, they argued that the social science of equity and inclusion was as important an academic subject and even less understood than any of the frontier work they were doing in chemistry, or in astrophysics, or what have you. And so they advocated that we should create a new essentially department, which would be a bona fide academic department, which would attempt to understand what multicultural societies and inequities in society as an academic subject.

And so after some time-- as usual in academia, you have a committee, et cetera, et cetera-- we created a new research center called which is now called the Haas Diversity Research Center after the Haas Family who have funded this initiative. And we committed 12 new faculty positions to create this center. But these faculty positions are in a way 12 plus 12 because all of the faculty members are both members of the center, but also members of some other academic department, so one half in each.

And part of our goal here was to ensure that this wasn't isolated, just a program that's off in one corner, but that we had faculty members from law, from economics, from public health, et cetera involved. And that is working quite successfully.

Interestingly, it has turned out that this has been very easy to raise philanthropic money for. And so to date, mostly the Haas Family, which traces its money's back to blue jeans. I encourage all of you to buy Levi's since it's Levi Strauss money actually, ultimately, three generations later. Very socially conscious, outstanding family. And so they plus the Hewlett Foundation have altogether contributed about $35 million to underwrite this effort, including six endowed chairs and a distinguished, a seventh, which is a distinguished chair for the director of this initiative.

So there are altogether currently six academic programs to understand educational disparities. That is how do we understand the differences in educational achievement among different groups, ethnic and otherwise, one health disparities, one to understand our democratic system in the United States works for some groups and does not work for other groups. Fourth is obviously economic disparities. Fifth is on gender issues. It's LBGT oriented, but in fact it's the women's studies department which actually is playing a lead role in this. And then the sixth is disability studies.

So each of these programs have five or six faculty members connected with them from all over the university. Interestingly, the program in disabilities is actually led by our humanities faculty. The social sciences, law, et cetera tend to dominate in the others. This has enabled us, these programs, to recruit to Berkeley some phenomenal new faculty members. One, Na'ilah Nasir, an African American woman that we managed to recruit away from Stanford whose research is on understanding the particular challenges of K through 12 and African Americans, the challenges that African Americans encounter in trying to master mathematics and science in high schools. And this is just absolutely brilliant new woman faculty member who's just been pretty extraordinary.

So along with this, and the person who overseas this is, one of the things we realized early on-- this also was faculty driven-- that we wouldn't make the kind of progress we needed to make, and I think we are now making at Berkeley, unless equity and inclusion was a part of every conversation. And the only way to guarantee that was to create a position of a vice chancellor, the equivalent of a vice president here at MIT, a vice chancellor for equity and inclusion. And so that person is present at every single meeting.

And you might say well, why for example should such a person be-- where does equity and inclusion come into capital projects? Well it turns out that if you want to be able to give minority owned construction firms an opportunity to bid, then you have to have your capital project broken down so that the size of the project is commensurate with building projects that minority firms can take on, et cetera. So equity and inclusion turns out to impact a remarkably broad range of activities that the university participates in.

So finally then, with the center, we currently have 12 FTE. But there are many more, a large number of endowed chairs. And we, in essence, have turned equity and inclusion from, if you like social programs at universities, to genuine academic programs. And we're very hopeful that the kind of scholarship which leads to Nobel prizes in physics, that we'll have the functional equivalent of Nobel prizes in equity and inclusion coming out of this endeavor.

So with that, I want to thank you, and I look forward to hearing our next two speakers.

[APPLAUSE]

KASTNER: Our next speaker is Heidi Hammel.

HAMMEL: Hi, it's great to be here. You know, I am a woman of MIT. I was an undergrad here. And then after escaping, I was drawn back into the fold for nine years. But I escaped again.

When I found out about this conference, I was very excited about coming here. And when they asked me to participate in the panel, I thought wow, that's great. But you know, this panel's about academia, and I don't know anything about that because I've never been in academia. And we'll come back to that a little later.

But when I asked, well what do you want us to talk about, they sort of had this laundry list which we never got to see. But the first one on there was work-life balance. And I said well gosh, I can sure talk about that. Because as you heard in the introduction, in my spare time, when I'm not running the major US astronomical facilities, I have three children who are ages nine, 11, and a daughter who's 13. So I know all about family issues. And I can talk about that not in an academic sense, but in a very personal sense.

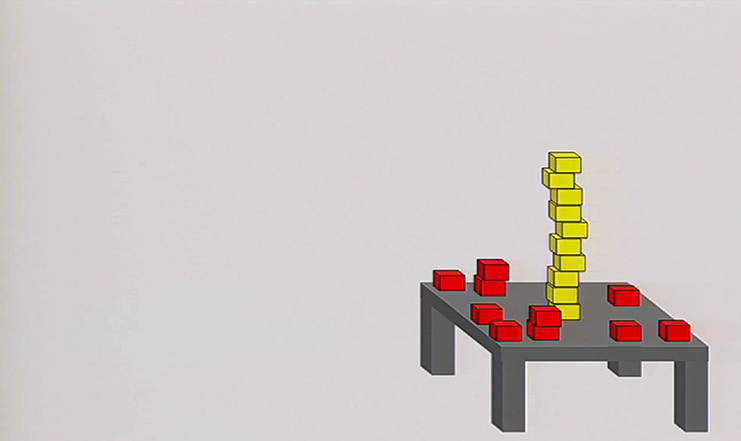

Now since I am a graduate of MIT, I decided to build a model of work-life balance. And since I am in fact a mother of school age children, I can build a model of anything out of things you find around the house. So here's my model.

[LAUGHTER]

This is my model of work-life balance.

[APPLAUSE]

It's made out of Dixie cups, and yarn, and tape. Taped it to some straws that are hanging from a blue crayon that has a pin stuck through it, for safety's sake of course. It's stuck into an eraser so you can't hurt yourself with it. Those of you who have small children know you've got to do stuff like that. But that's just the model. There's more.

We got to have our simulated work and life. So here's life. Yellow LEGOs, life. And here's work, the red LEGOs. So can you help me with this? And help me. That's a very important lesson young ladies. Always ask for help. Always, always, you need help.

So all right, so let's see. I said that this was life. Every morning starts with life, all right, because you've got three kids that you've got to get up and get out of bed. So the scale instantly tips down. And the other morning, it was like three days ago, all three kids were sitting at the breakfast table, clothed, eating breakfast-- not fighting. I just took a step and I said, I'm super mom. All my children are dressed, eating breakfast, and it's half an hour before the bus comes. It's great.

All right, so they go off to school and fine. And you say okay, now I'm going to start working. Okay, so the scale goes to work, all right. But immediately the phone rings. It's your nine-year-old. Mom-- mom, I forgot my viola. Can you come pick it up and bring it into school? Okay, all right. It's fine. So you leave work. You go, you take the viola in.

And then you get back to work. And the phone rings again. And it's your job, people saying, oh Heidi, you didn't ever turn in your technical reports on that grant. So NSF won't send any more money to our facility until you send it in, now.

All right, that's all right. I'll do that. No problem, no problem. And you go along. And then you realize, oh my god, today is the day the reports are due for the telescope. You got to do that too. So you do all that.

And then the phone rings again. And they say to you-- it's day care calling. Your daughter, she has head lice.

[LAUGHTER]

Come pick her up. And she can't come back for three days of being nit free. All right, so that's an interesting thing. And so then life goes on. These are true stories by the way. It's absolutely a true story.

And so then we're balancing here. And this is just a regular-- you all know what I'm talking about. The proposal's due-- the proposals due, and your printer runs out of ink. And you're on backup ink jet, so you got to run off to the store and do that. And in the meantime, your son, he calls you. Mom, we got to go, because I need this thing to do my report. And see what happens to your scale?

[LAUGHTER]

Now that's only about halfway through the day. In reality, this is what a day is like. There are sizes and shapes of crises you never dreamed of.

I was thinking of asking one of these guys to dump this over my head for dramatic effect, because that's what life if really like as a mom and working full time. But I figured then this would look just like my living room floor and I'd have to pick them all up, which is where I got them from any way the day before yesterday. So I'll put these over here to remind you about work-life balance.

My message though, pertaining to our subject today, is that in fact, we are the scales. We are this broken straw. Our goal here, what we're talking about today, is how to keep this strong. Because those things are going to happen. Anybody who works in academia-- or doesn't work in academia in my case-- you have to deal with this.

So what are the things that we can do to help? The kind of things that you heard Bob Birgeneau talking about is those are policies that help strengthen this. They help. They won't solve the problem.

And I do want to say this. I was really conflicted about sharing this information with you here today, because this is a celebration of MIT, and a celebration of all the progress that has been made at MIT. And believe me, as someone who was here 30 years ago, I can tell you the progress has been considerable.

But-- and that's the caveat, this celebration with caveats-- all these amazing programs that you've been hearing about, and that you just heard about at Berkeley, how would they have helped me with my first child here at MIT? Not in any way whatsoever, because I was not a faculty member here. I was a research scientist. A principal research scientist, it's very nice, but all these programs for faculty don't help people like me. And there are many people here, many young women here who won't necessarily become faculty members. What are we doing to help them? Those programs for child care, wow. Wouldn't help me. The programs for assistance, wouldn't help me.

So how did I make it? All right, I found an organization. When I had the dual career problem, the dual couple-- my now ex-husband took a job somewhere and I had a baby, and we moved there. And MIT said, you've got to be up in Cambridge. And I'm like well, I'm not. I'm in Connecticut. And they said well, choose.

So I chose to leave MIT at that time. And I got a position with an organization called the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. But they allowed me to work in Connecticut where my family was. And in fact the Space Science Institute, the research branch there, 1/3 of our organization is not in Boulder at all. We're spread out across the United States. We're anywhere anybody wants to be, but we work remotely from our homes. It was terrific, absolutely terrific opportunity.

And I also am very proud of the work I did at Space Science Institute because the Institute itself was committed to diversity, women like me, gender issues, it's not an issue. We had lesbians working for our organization openly. We just talked about-- it didn't matter. Anybody who had work to be done got a research grant. Space Science Institute would work for you.

I left Space Science Institute just this past January 1 because I was offered the job opportunity of a lifetime. And I decided it was time to take that opportunity to go to try to make the next generation of space facilities available to young people. Whether it's space telescopes, whether it's ground based telescopes, I have an opportunity to do that. But I was very upfront with them. I said look, I've got this issue right now where I've got kids. We're in Connecticut. I'm not moving to Washington anytime soon. They said okay, we'll make that work for you. And so right now I'm commuting to Washington and working remotely.

And it's been working out very well for me, I think because I knew that it would work. I told them it would work. I said this is going to work, got to make it happen.

So I guess the message that I want to get across to you today is twofold. First of all, it is not easy being a full time working scientist, an academic, and a parent. I mean, you heard that, but I just need to say it over and over again. I am so glad that MIT and other universities are recognizing that and taking proactive steps to make it easier, to make it possible. At the same time, I challenge all of you, particularly those of you who are working in the highest levels of academia, to acknowledge, to recognize, to remember that there are young people in your midst who are not on the faculty track. So please, please be aware of that, and let's see what we can do to help those young people. And I think I'll leave it that and answer questions later.

[APPLAUSE]

KASTNER: And our last panelist is Lisa Maatz.

MAATZ: Well I hate to disappoint you, but I don't have those kind of visuals. Hopefully I can keep you entertained in other ways.

I'm so glad to be here. AAUW has had such a nice history, a rich history with MIT, and with the Boston area actually. We were founded here in Boston back in 1881. And I like to call those 17 women kind of the original uppity women because they had college degrees and they had the nerve to actually want to do something meaningful with them. They also wanted to have more women join them in the ranks of college graduates. And so when you think about it, back in 1881, that was a pretty rebellious thing to do. And so we're very proud of that history.

AAUW has been working in the STEM field for a very long time. We have over 100,000 members and 1,000 branches across the country. And our work really centers in a variety of different ways. We do research. And one of the things we've done most recently in this area is a research report called Why So Few? that I hope many of you will take a look at on our website. You can download it for free.

We also do public policy work, which is the work that I do. I have to admit, I'm a lobbyist, but I do use my powers for good. I swear. And one of the things that we do within the public policy realm is look at some of the best practices that we see coming out of research, coming out of reports, and so forth, and trying to put that into action, trying to make sure that programs that we know are good get the funding that they need to continue. As you can imagine in this particular environment, that last one is a bit of a challenge.

We also do wonderful programming. Just was in Buffalo, New York, for instance with our Buffalo branch. And they had their sixth annual Tech Savvy day, which was 500 11 to 14-year-old girls for a day long kind of symposium, camp, workshop, what have you, on STEM, on all kinds of different hands on models that they could do and enjoy.

Even more importantly, they also had 200 of their parents going through the day as well, on a separate track, talking about things that parents need to do in order to keep the STEM field open to their kids, in order to make sure that they're a viable option if their kid has that interest and how to encourage that interest, especially in girls.

But our history also goes back to fellowships and grants. For those of you who might not know it, I think this is one of the best kept secrets about AAUW. We give anywhere from $3 to $5 million a year for women's postgraduate work, for doctorates and so forth for graduate degrees. Because especially back in the day, we were trying to put our money where our mouth is. And one of the things that was really an issue for women faculty, and for women who wanted to be faculty, was to get research money. And it was harder for women to get research money, so the AAUW women said okay, well we'll give them the research money. Doesn't matter where the money comes from, right?

So actually one of the first things that we did that we're particularly proud of is that we were the ones who bought Madame Curie her first gram of radium, which back in 1920 cost about $150,000, which now is over $1.6 million. So those are the AAUW ladies. They put their money where their mouth is. And on this particular issue, we definitely have some street cred.

One of the things that I want to focus on is things that we're talking about in terms of how to get more girls and more women into the STEM field, and also how to deal with the climates issue. Because one of the things that we know, of course, is that there's a leaky pipeline. And so you kind of lose girls and then women along the way in various science and STEM fields. What can we do about that? How can we kind of be vigilant and try and stem that leaky pipeline?

So one of the first places we try and do this obviously is in education. Many of you, if you're watching the news, might know that one of the things they're talking about in Washington, DC, aside from the budget and whether to close down the federal government-- which at this point some of us think might now be a bad idea. But essentially one of the things they're talking about is reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Act, also known as No Child Left Behind-- not a really popular law. One of the things that happens with No Child Left Behind, because its emphasis on testing-- it's a do or die, winner take all emphasis on testing-- is that they teach to the tests. So if all we want our kids to be able to do is to read and do math, that's fine. But you look at any school's curriculum now and you will see a huge drop in science-- a huge drop in science. I don't care if they can add, multiply, and divide. If they don't actually go in and do some science work as well, if they don't go in and do chemistry work as well, they're not going to be able to use that and apply that in a way that could be useful.

So one of things we're talking about in the reauthorization is, number one, no more high stakes testing. Testing is a useful tool, but it should not be the only thing we use to measure achievement. Number two, let's make sure we're getting science in there, because we're kind of missing the boat here, and in that sense really not preparing our students.

The other thing that we have talked about is of course trying to get more kids into AP classes. Unfortunately, one of the things that we see with girls in high school is that they take the AP classes, but they don't take the AP test, which I find very interesting. Now they don't take the AP classes in the same rate as boys do, but still, it's not that big of a difference. The problem is in taking the test. And so what's going on there that we need to address to make sure they're taking that next step?

We also want to make sure, of course, that we are, as I said earlier, dealing with the parents. Because one of things that we know from AAUW's own research in the Why So Few? report is that parental attitudes, parental notions about what kind of work is appropriate for girls and what kind of work is appropriate for boys obviously can have a huge influence on a kid. And so having a conversation with parents and actually working through some of those issues can really make a difference.

The other thing, of course, that we've seen is that when you talk about trying to get more girls into STEM, you actually need to start talking about middle schoolers. Because if they haven't started taking the math classes in middle school, they're not going to have the preparation they need for the right math classes and science classes in high school. So actually, in a very real sense, especially with today's kind of curriculum issues, you could actually kind of put a girl off the path of a STEM field in seventh grade if you don't get her into algebra. Because if you don't get her into algebra then, she's not going to progress fast enough. She won't be able to take AP when she gets to be a senior.

So these are decisions that-- parents already have it tough enough, but they need to be thinking of probably even sooner than they had probably thought of originally.

Another thing that we've been talking about, and I said before, we try to put research into practice. There was this great report that came out from the National Science Foundation called Beyond Bias an Barriers. And it was looking at women in academia. And one of the things that they put in as a recommendation, which I thought made a lot of sense, especially given what Heidi just talked about, was the way that the government structures its grants. And one of the things that-- we actually have a bill that we're working with Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson from Texas on is to make sure that when grants are given, there are allowances made either to pay for child care, or potentially to pay for kind of a replacement scientist if you need to go on maternity leave or paternity leave.

Because the reality is, especially for some science experiments and such, cells aren't going to stop dividing. Things aren't going to stop growing. Whatever your research is is going to continue even if you want to stay home and do some things for a newborn. So having that flexibility I think is going to be key.

I think of the most profound things though that came out of that report is something that probably will surprise some of you. Donna Shalala was the chair of that particular committee. And one of things that she said when she was testifying before Congress was look, I run a major research institution. I also happen to run a major athletic institution. Now I can tell you exactly where my university stands in terms of Title IX when it comes to athletics. I can tell you what we do with our coaches, how many resources we give our teams, the number of male athletes to female athletes. I know exactly where we stand. Part of the reason for that is because we're a member of the NCAA, and they require us-- and the federal government by the way requires us through the Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act to report those statistics. So I know. I know where we stand.

Now a lot of you might not know it, but Title IX actually applies to any federally funded program that receives federal money, educational program that receives federal money. That means you cannot discriminate based on sex in any program, any educational program that receives federal funds. That means that we can use Title IX as a tool to advance girls and women in STEM.

We can do this through compliance reviews. One of the things that has happened and been very interesting at the federal level-- even if you're not getting a grant from the Department of Education, if you are getting a grant and it is educational programming or it's going through an educational institution, you have to be in compliance with Title IX. So if you're getting a grant from NASA to look at some things, you have to be in compliance with Title IX. NASA has actually started doing its own internal compliance reviews to make sure that they are following what Title IX says it should do. That's a key thing. That's a tool we already have in our toolbox, if only we would use it.

We have seen a huge growth in the number of girls playing athletics ever since Title IX was passed in 1972, like a 900% increase in the number of girls playing sports in high school. That's huge. That's an amazing growth pattern. Imagine if we could do that with STEM. Imagine if we could use Title IX in the same way, the same tools, with the same focus. Imagine what we would have.

And that's not just about giving girls an opportunity to play ball. Because that's important, girls who were active in sports, they're much more likely to graduate. They're much less likely to get pregnant. They don't use drugs. They get better grades, all that stuff.

But one of the things that we know in terms of using it in terms of STEM, we don't have that kind of NCAA like institution. And that's one of things that Beyond Bias and Barriers actually recommended. We need to come up with some kind of quasi-governmental institution that has the same kind of data reporting requirements that sports do. If we have to report about sports, why not have some information about the STEM fields? And do the same kind of work there in terms of building up women in the STEM field.

So that I think is a particularly workable kind of solution because there's so much money that flows from the federal government. There are a lot of people who get those grants. And one of things that it says, are you in compliance with Title IX? And they just have to check a box. I would like to have them do more than check a box.

And oh by the way, if you're one of those folks who get those grants, you should know that the Office of Civil Rights at the Department of Education is now expecting you to do more than check the box. They're actually going out and proactively, randomly selecting universities to do compliance reviews where they come in and they see if you're doing okay. And it happens.

Notre Dame had one a couple years ago. And one of the things that came out of it, which I thought was fascinating, and is actually I think very demonstrated in AAUW's Why So few? report as well is that they realized they needed to kind of restructure their curriculum, that they really had this huge leaky pipeline in the engineering field with women at Notre Dame. And they looked at the curriculum, and they realized that the first course they have people who are declared majors in engineering take is kind of a weed them out math course. It's the very first course they have them take.

So there were a lot of women who, even though they might have gotten through that math course, actually changed majors fairly quickly after that. So they changed the curriculum around and actually have, as their first course now, more of an introduction into what engineering is, what engineering can do. The reason why this is important is because one of things we now from girls and women in the sciences is that a lot of times their interest stems, not necessarily most immediately from the science, but how can they use it to help people? How can they use it to make a better world? How can they use it to improve their situation and the situation of others?

And so if you have a course that shows them that before you then get into the more esoteric kinds of nuts and bolts about how it works, you can actually then help them see how these classes all apply and how they kind of build on each other. A really good example of that we were just talking about recently, it wasn't until just a couple years ago that the crash test dummies actually started to be-- started to use crash test dummies the size of women. Now if they had been using crash test dummies the size of women when they started using airbags, we would have found out sooner that if you're a 5'2 women, 100 pounds soaking wet, an airbag is not your friend. There has to be an adjustment made to it. But because we were only using male sized crash dummies, they didn't know. And we had to actually have all those injuries and deaths to prove it. So that's a place where the applied sciences in many respects for women and girls can make sense, a place where they feel like they can make a difference.

The other thing that I wanted to mention real quickly is just some other things that we are doing on a policy level to try and make STEM fields more open to women and girls. There was a lot of talk about childcare. I think that's a huge issue. Federal funding for childcare unfortunately is under attack at the moment. We've been trying to not only increase that finding, but to get them to be a little more common sense about how to use it so that it's not like an 8:00 to 5:00 childcare, that it also runs at night, that it runs on the weekend, that it works for graduate students and faculty members.

Some other things that we have been looking at is trying to make sure that when you have campus policies put in place, that there's a real kind of thought processes about consequences and even unintended consequences. One of the other things that Notre Dame did as a result of their Title IX compliance review is they actually ended up putting together a dorm, a residence hall, that was just for women in science, a STEM dorm essentially. And having that cohort, they called it the posse effect. Having the folks around them was something that was really useful in terms of keeping them in the program.

So let me just stop there. I'm happy to take any questions. And I do just want to say again, thank you for having us here today. This has really been a great panel. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

KASTNER: So now we'll open the floor for questions. I'd ask you to come up and use the microphone if you have a question you'd like to ask.

AUDIENCE: Let me pick up on Heidi's comments, and I hope it's not an embarrassing question that I'll ask our Berkeley and MIT deans and chancellors to answer. To what extent these new programs are reaching into the postdoc and graduate student levels these days?

HAMMEL: And research scientist levels.

KASTNER: So let me ask Bob, because I think we all feel very strongly that daycare in particular should be provided to a very broad community. But we haven't figured out a way to do it at MIT without bankrupting ourselves. So I'd like to know how you've managed this for the graduate students.

BIRGENEAU: So in California-- so first of all, in terms of the research scientist, I think Heidi-- I agree with everything she said actually. She made a really important point there. It happens at Berkeley. The research scientists primarily at appointed at Lawrence Berkeley Lab. So actually we don't have the equivalent ladder at the University because they're at the laboratory, which helps a lot in terms of some of these programs like child care.

So as I mentioned, we have 250 child care slots. 80 are reserved for faculty. So there's 170 for postdocs, graduate students, and undergraduates. The caveat there is the postdocs could not possibly afford it because it's not subsidized for postdocs. So for graduate students and for undergraduates, it's very heavily subsidized, partly with state funding. Although that's under threat in Governor Brown's budget right now. So through a combination of-- graduate students all qualify as impoverished people. So they sort of automatically are eligible for these state programs. So we're able to make it affordable for graduate students and undergraduates.

Our postdocs at Berkeley now are unionized. And we have not-- and I anticipate, as they get better organized, that we are going to start seeing demands for child care from the postdoc union. And that would be very interesting to see how that evolves.

AUDIENCE: Hi. I have a question for both Bob and a little bit for Heidi, which is more about graduate students. I'm a science dropout after I went through my postdoc. When i was in a biology graduate program at Tufts, in my lab-- well in a different lab, the tenured woman professor dealt with the child care problem by nursing her baby at school. And she would interview prospective graduate students nursing her baby. That's one approach.

Another issue I'd like to just bring up is other family emergencies. For some odd reason, most of us-- in one way our fathers died. And one woman was from Korea. And she came to me and said, when her father was dying, should I go home? Should I interrupt my research and go home? And I told her she had to. Her husband asked his advisor at Brandeis the same question. And that was only his father in law. And that adviser said of course you have to go home home. So I'm just saying that there are a few other areas there that could be thought about.

HAMMEL: I can answer too. Yeah

BIRGENEAU: Yeah, we'll both answer. But I'll just say, first of all, as a senior administrator, but also as someone who has a daughter who's in exactly Heidi's situation, almost word for word except she's a faculty member at BC-- or Boston University Medical School, and was an MIT undergraduate, and served very well by MIT as an undergraduate by the way.

So two changes we've made relatively recent at Berkeley is that we extended the child care down to three months of age, the infant care to address exactly this issue. And that's relatively recent.

Now that is extraordinarily expensive, because of federal laws connected with care of infants, and so it has to be heavily subsidized. And then the second thing is we've generalized our emergency care to take care of essentially every situation. And we encourage people to go home and address issues of crises in their home.

You know, whether or not-- in any individual department there is a department chair who's a throwback, that's very difficult to control, but we do.

KASTNER: That doesn't happen at MIT.

BIRGENEAU: No, ot doesn't have at MIT, only at Berkeley right. But we do our best anyway. But I think Heidi can probably discuss this better than I can.

HAMMEL: So with my three children, all of them I nursed for over a year. And I was fortunate in that, for the first year, while I was still at MIT, I had an office that had a door. And the Madela breast pump is your friend.

I traveled extensively. For my job I have to travel. And so take that breast pump along and you keep the milk coming. I think what universities can do along these lines in situations where you may not have an office with a closed door, in addition to the day care facilities, they should set up lactation rooms so women can have a safe, clean place to pump so they don;t have to sit in the bathroom or some other horrible situation, Which. I've had to do.

MAATZ: In fact they have to. Little known provision under the health care reform law that passed late last year, and now there's been regulations issued is that any organization-- it's very much like the FMLA, Family Medical Leave in terms of who's affected. If you're an organization over 50 employees, you must have a private room made available for women to pump as needed. It cannot be the bathroom. And it is now required. So that actually gives women another leg to stand on in terms of asking for that kind of space.

HAMMEL: So there. So now--

KASTNER: Let me just comment that the School of Science has already done this at MIT. There's lactation room within a five minute walk of every lab or office in the School of Science.

HAMMEL: It's so wonderful that all these things have happened since I left MIT. Let me address the other question you asked though, and that's about personal family emergencies. Any time there's a personal family emergency of any level, you should be able to go to your boss, your advisor and say, I've got a personal family crisis. And if they don't say, go deal with your family crisis, then you need to talk to your HR people, because your family has to always come first.

AUDIENCE: My name's Catherine Wyman and I brought eight students from Xavier College Prep High School in Phoenix with me to this symposium. And we are very excited to be here.

[APPLAUSE]

I really enjoyed your panel Lisa. We've relied heavily on the Why So Few? and other research documents from the AAUW. And it has helped inform a lot of what we do. When I started at Xavier two and a half years, ago one of my colleagues-- we have an art gallery on campus and she's an MFA and curator for the gallery. And she came to me after I'd been there about a week and said, have you seen this data? We've got a problem with women studying science, technology, engineering, and math. And we started an event. Founded by the artist, the artist and I got-- she says a right brain and a left brain got together and had Girls Have IT Day!, which is an event to encourage middle school girls in STEM fields. We had 400 girls on campus on Friday. And I think that a lot of that is due to-- 400 girls, excuse me, and their parents.

A lot of that is due to your efforts. And I appreciate that. And Heidi, I could relate very, very well too, everything you had to say. And I just want to throw a shout out to American Airlines for helping me when I had my Medela breast pump and had a flight delay in Chicago.

But Bob, I had a question for you about your statistics and the increase. I enjoyed seeing that increase in women professorships at UC Berkeley. And I wondered-- it didn't split out by field. And I wondered, was that across the border? Or what were the numbers in the STEM fields?

BIRGENEAU: So that's across the board. In STEM fields, our numbers are not very different from MIT's. 20% of our faculty in STEM fields are women. Been going up gradually, but not as rapidly as we would like. And I do have to say, because I don't want to be Pollyanna-ish here, we have continuing challenges in two department, one of which I happen to belong to, which is physics. And the second is electrical engineering computer science in terms of women graduate students. And so we've made tremendous progress in most departments, but frankly not in either physics or EECS, in spite of the fact that in the physics department, the current and previous department heads are women. The department head is an outstanding, outstanding scientist.

MAATZ: If I could just jump in there. One of things that I noticed about the MIT report that I think we found at other campuses as well is that very interestingly, that progress has a double edged sword. I mean, you look at the numbers and you're so glad to see more women faculty in various positions, more women in senior leadership team positions. And then though you have those faculty reporting that, some people are starting to think that well, is the bar as high for women because they've been working so hard to get women, and kind of questioning whether they actually would have gotten in under a regular kind of process.

And that I find unfortunate. But I do think it's part of the process moving forward and just diversity as it goes. It's always going to be a bumpy ride. So the fact that the progress is being made is good. But we also have to deal with, in some respects, the consequences of our progress in order to then make the next step forward.

AUDIENCE: I have a technical question about Title IX. My understanding is that one of the reasons we know so much about Title IX in sports is because the Title IX sports implementation was delayed because it was perceived as being especially difficult to implement. And there were a series of pieces of legislation that were passed for the implementation of Title IX in sports.

What I'm not so clear on is what Title IX compliance in STEM looks like. And I don't know that there's been any specific legislation that lays out what Title IX compliance in STEM looks like, or anywhere in higher education for that matter in the educational programs of higher education. I know that a number of programs that have benefited-- women's graduate education for example-- have grown out of Title IX. But I'm unclear on what academic Title IX compliance in STEM looks like.

MAATZ: Well you're right about athletics in the sense that actually all of Title IX was not actually implemented for more than three years. And A coalition that I chair called the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education was actually founded because the government was dragging its feet in terms of implementing Title IX period.

So the Title IX regs finally starting to come out in 1975. And there was a big battle about how sports would be handled. You'll be interested to know that one of the biggest players in that fight were football coaches. And one of the things that they were concerned about was how the numbers would play and so forth. They were actually the ones who advocated for proportionality, never thinking that women might actually start surpassing men on college campuses.

In terms of STEM, there's a couple of things that go on. Number one, obviously there are the regulations for Title IX itself in terms of what the law states. You can always contact the Office of Civil Rights at the Department of Education to ask for more. But interestingly enough, this particular issue is one that we've been able to convince the Obama administration to take up. And so while there are good examples of Title IX STEM compliance reviews out there-- and I mentioned NASA as a specific great example. And you can go to NASA's website and find it. You can go to OCR's website and find it as well.

What's actually also going to be happening later this year is that OCR is going to be putting out specific guidance on Title IX in STEM. And we've not had that before. So while it's been mandated through legislation-- Ron Wyden was the one, a senator for Oregon, who was the one who started making NASA do their stuff through their appropriations, right? I mean, if you tie it to money, you can get folks to do just about anything.

And at that point, that's when we started having some good working models. But there are compliance reviews going on right now, 10 different schools getting compliance reviews in terms of Title IX and STEM this year. And the guidance should be out, probably I would guess, September for back to school.

KASTNER: Sarah?

AUDIENCE: I'm switching topics again. And this is when the women scientists were asked to give the talks. We were not asked to talk about our personal life. So I have a couple of comments for work-life balance, which are in direct contrast to Heidi. So you're welcome to argue with me offline or online, whatever's appropriate.

But I will say a couple things. One is I also, unfortunately, have to operate like a single mother. So I do breakfast, lunch, dinner, shopping, et cetera, et cetera. And my family, some of the things you described, they're actually not acceptable. So if the child forgets something or something goes wrong on the order of I to do something, it doesn't happen. And then the next time, hopefully it doesn't happen again. Those things like lice-- I mean, I'm really, really hoping that what you said isn't like an everyday thing and that you just chose examples. I'd like to know actually just to sort of show the worst case scenario.

And what happened to me actually was quite different. I never thought this was possible because when I was younger, probably right up until I had kids, I was probably the most unorganized person alive. And one of my female professor friends at another university, who does not have children and will never have them, calls it the motherhood gene. I don't know if this is true or not, but it forced me to go to an unprecedented level of organization, which I actually thought was not possible at all. I wish someone had took me aside and said, you know what? This is something I only learned two weeks ago. You only have to do grocery shopping once a week. I honestly didn't know that. I used to go like every two days. I actually figured out how to do it. I'm sure everybody already knew this, so why didn't they tell me? Like the fruit that you want to give your kids for lunch, the things that will go bad that are really yummy, they can get that Monday and Tuesday. And sort of by Friday they get the apples. You guys knew that? You should have told me. Took me a long time. I learned all this stuff from scratch.

I used to think that cooking would take forever. This has just been unfolding. We learned how to cook steak very quickly. So I can actually-- I'm not happy about doing this, but I do the stuff, okay? So I've mentioned this.

And then the other thing was about work. So we have the work-life balance. The other thing is about work, that I now choose how I spend my time at work exceptionally carefully. I always thought I did this, but now it's even at a higher level. And when I do that, I don't waste time. But I do still have enough time to sort of hang around with my students or do stuff. And so for me, the work-m life balance was-- I wouldn't call it like a tragic level of organization, because who wants to run their life in a way that is like, run my personal life like a business. It's ridiculous.

But on the other hand I did. And I found I benefited. And I'm still sort of striving to come to some equilibrium. But that stuff that you mentioned, I just wanted the audience to know, I wish we could have-- we didn't want the conference to be dominated by everybody complaining about their personal life. But I wanted you to get another perspective.

And I'm sure this will change. And there's some months or windows that will be horrible. But on the whole, it's streamlined. And it's not a pleasant thing to have to do everything, but at the same time there's a great way to do it. And I love my kids, and my job works out well.

And I'll leave you just with one piece of advice of how to make it all work, at least what I think. First of all, if you have extended family, try to live near them or have them live near you. I have no family unfortunately. Other than that, try to negotiate to get paid well enough so you can pay for things like having other people help you with the chores to make life a little bit easier. Okay, and you're welcome to respond if you want.

HAMMEL: Sarah and I often disagree about things in public. It's become a habit of ours.

AUDIENCE: Be a bit brief.

HAMMEL: Okay, sure. No, in fact I agree with nearly everything you said. A lot of what I talk about I use for dramatic effect. They are all true stories, but they don't happen on a daily basis, especially head lice, thank god.

I do agree with you. I have a housekeeper that comes. She Is worth her weight in gold. And what I pay her is worth every penny. I don't have family nearby. My mother's only 2 and 1/2 hours-- she's 2 and 1/2 hours away, so she can help out when I'm on trips like this.

But I'm a single mother. I'm divorced. So there is no other person. It's only me. It makes for very different things.

One thing I don't agree with you is that you can be balanced. I think you could integrate over a week and be balanced. You can maybe, if you're very well organized. And I agree with Sarah that you go to new levels of organization when you're a working mom. And that's why people ask you to do more stuff, because you seem to get stuff done, because you have to to move on. And then they ask you to do more things, but that's a whole nother issue.

But I think at any given moment, things happen, and the balance swings. And if you think that at every moment of every day-- now Sarah, she's in a different class than me I guess. But for me, any given moment, I'm swinging back and forth. And if I can get five hours in the work zone, I think that's a really good day. And then there's the other times. I don't think there is a balance. I think it balances over the long term.

AUDIENCE: I want to not draw this out. I just want to say thank you. I just wanted to hear whether or not that will happen to me one day. So thanks a lot.

BIRGENEAU: I have a question for both of you. And an empirical observation, I mentioned that I had a daughter who was an undergraduate here at Berkeley during the '90s when all this was happening actually. So it was fun to hear a woman's student perspective. But now that she's a faculty member, she's super organized. Single mother of three, just like you are. And the consequence of that is that she's by far the best organized young faculty member in her department over in the medical school at BU. So every single time there's a committee to be chaired or it has to be done, the department head asked her because she's clearly the most competent young faculty member in the department. And then she always calls me, my phone rings. She says dad, the department chair just asked me to chair X committee. What do you think, et cetera, right? And it's very complex. And so I'm interested for both of you, or maybe anyone else in the audience, just in trying to give her advice actually.

AUDIENCE: The first rule is to say no as often as possible. But don't tell Marc or Ed I said that. And the second thing is, I have benefited tremendously from this level of organization with my exoplanets sat project where I showed you the demo model. So it's completely true that it carries over into other aspects. That's what I'll say.

MAATZ: One of the things that we've seen from the Center for Work-Life Balance in Academia, when they talk to women faculty and male faculty about this particular issue is that academia isn't that much different from the rest of the workplace in that there's kind of this maternal wall, so to speak. Used to call it the glass ceiling, but it isn't so much necessarily women as it is women with children. And we see that in the pay gap and how that manifests itself.

AAW's done a lot of study on wage discrimination. And one of things that we've seen is that even when you compare apples to apples-- so in other words, one year out of college, have the same major and go into the same field, there's already a 5% gap. 10 years down the road, even though women are more likely to get a master's degree, again same major, same field, severe regression analysis to make sure that we're comparing apples to apples, there's a 12% gap. So the farther up the food chain you go, the bigger the gap, which is a huge issue.

But the other piece there is that there kind of is this assumption that women's lives revolve around their biology, and women who control their biology get rewarded and paid more. Now what's interesting though is that when you look at wages for men, men who have children actually make more than men who don't, whereas women who have children actually make less than women who don't.

So while I can appreciate not necessarily wanting to get hung up on this, at the same time, women and men are both still very much constrained by cultural expectations about what they're going to do and what they're going to focus on. The Family and Medical Leave Act, and it was passed back in 1993, one of its actual stated intentions was to help to dispel stereotypes about what was appropriate work for men and women, and to try and encourage men and women to equally share child care. There's lots of debate about whether that's been useful or not. But I do think that these are things that we can't ignore because the reality is there are assumptions being made on our behalf. And so we do have to address them.

HAMMEL: Let me answer his question too because he asked me. Tell her to say no. That's what Sarah said. And also evaluate things very strategically. I get asked to give talks all the time, but now I only give them if they're local-- not even that anymore. But you have to evaluate all these requests very strategically and make sure that you're getting the best value for your time.

KASTNER: Glad you agreed to come.

AUDIENCE: Two remarks and a question. First on work-life balance, I don't want the dads or the men in the audience to think that they should be let off the hook. It is very important for both parents to support and work with their children. And this is really becoming an issue for young male graduate students, postdocs, research staff, and faculty.

I think that there are advantages to parenthood in terms of organization and leadership. Maybe one of the reasons why the fathers rise up is because in fact they can develop some empathy and some ability to work with people. I can speak there from personal experience. Being a parent really helps.

The second observation is that my department, actually when Marc Kastner was the head, had a NASA Office of Civil Rights Title IX compliance review. Actually it was spread across our two terms, the end of his and then the beginning of mine. We were thoroughly assayed and reported favorably. The department was fine. There were some issues about having information posted on compliance officers, university regulations, and so on. But anyone who wants to know what it was like to experience a Title IX review in academia can read a little piece that I wrote for the MIT tech student newspaper, which you can find by just googling MIT Title IX.

And then the third, the question which is really directly to you Lisa, follows up from something that Abby Stewart said this morning, which is that one of the ways that we can improve university climates is to have climate assessments. Some professional societies do this. The American Physical Society, their Committee on the Status of Women in Physics and the Committee on Minorities have climate site visits. I know that AAUW, I believe, does as well. Could you say something about that please?

MAATZ: Yeah, AAW's research on this issue goes way back. In fact I think AAW first kind of got lots of press when we started-- we came out with a groundbreaking report back in the '90s called How Schools Shortchange Girls, and since then have done a variety of different studies. And the one specific to college campuses we did one just recently in the last couple years called Drawing the Line, which is about sexual harassment on campus.

That's another thing that I should certainly make you aware of is that if there were two issues that I were to pick that this reinvigorated Office of Civil Rights is focusing on, it's STEM and it's sexual assault. There's going to be new guidance coming out on sexual assault issues as well. And I think that part of the reason for that is that there were just too many stories of people who were harassed, both men and women by the way because Title IX is gender neutral. And the antiharassment provisions are the ones that men most likely use. But too many people who've been harassed and literally harassed out of their majors, harassed out of a certain class. All of us know that there are situations where if you miss taking the class in this winter semester, you're not going to get a chance till next time and how all that works.

So there are ways to do assessments. In Drawing the Line, we have a sample survey that colleges and universities can use in order to address that. We are going to have new research coming out, but it's going to be basically middle school and high school on harassment, but also including the whole cyberharassment issue and climate issues.

But I do still think that will be instructive for college campuses because these are incoming freshman. And so what they learn that's appropriate, what they see that's challenged or not challenged in high school is certainly going to help inform their behavior in college.

So one of the things that we found with the whole climate assessments is that-- and I hope you found this the case with the Title IX compliance review-- is that people are really hesitant at first. They want nothing to do with it. But then when they actually find out what it is and see that it's not intended to be a pejorative thing, it's literally to kind of show you how healthy your campus is and ways for you to become more healthy and more proactive, that it actually can be affirming thing to see the good things that you're doing, but then also to get good ideas for things that you can do perhaps even better, or new things that you can institute.

AUDIENCE: Again, thank you for coming. And thank you for tracking the data on women and faculty. But I too am-- like you look at staff, and I spent 10 years on the staff at Stanford and MIT, about five years at each university, as an engineer-- not as a research scientist-- in facilities. And I never worked with a female plumber, a female electrician, or any female tradesman ever. And they do exist. I was just at a job the other day at Genentech not far from here, and they had two female electricians on their staff.

So when you look at communities, we really need to look at gender and ethnicity and race across the entire community. And likewise, administrative assistants, I don't remember ever running into an administrative assistant that was a male at MIT. I did at Stanford. I know quite a few at Stanford.

But certainly in the trades. And I can tell you as an engineer, I really want to know how to use tools, and I would have probably had more comfort level working with women electricians on some issues so I could be a better engineer. Thank you.

MAATZ: The career and technical education issues are huge. I think a lot of times when we think of nontraditional jobs for people, academics, we think of STEM. But there's always these nontraditional jobs in the skilled trades where people can make a good wage, get benefits, much less likely be outsourced to another country. And so there's been a lot of work particularly through welfare programs, but also just through retraining programs from the manufacturing sector, both men and women, to get more women into the skilled trades.

It's been tough. Because I would say actually if you sat a woman plumber down with a woman engineer and they talked about climate issues, pay and promotion issues, they would have a lot of things in common to talk about. So it's interesting, and perhaps even a place where we can look to for additional best practices. They may seem like disparate fields, but they're facing a lot of the same issues.

HAMMEL: And this comes back to climate, always comes back to the climate of the institution. And so I hope that the people here who are in charge of these academic facilities are hearing that message, that it is not just academia, it's the broader climate issue.

KASTNER: Last question, Hazel.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. I'd like to thank the three of you for really interesting presentations. And I have two questions which are related. One is for Bob and one is for Lisa, and maybe for Bob as well, perhaps for Heidi as well. The question for you Bob is, in this interesting diversity center that you've put together where there's going to be interesting research coming out, do you have a mission or some kind of actionable items that are part of the whole process of the center in that it's not just research, it's going to be research that will change climate? Because part of the job of the faculty is to suggest ways to actually take the research and move it into actionable change.

And then I should just say the second question because they're kind embedded, which is the question of the role of universities in addressing elementary school education and the climate that children are exposed to from-- actually before elementary school, preschool education, which I think plays a huge role in helping kids figure out whether they're going to go to the LEGO side and become engineers or go to the baby carriage side and go on a different track. And so that's also an actionable question, and I'm kind of mixing them up so I don't take too many question times. But you see there's the question of action items, and then the role of the universities in getting involved in very junior educational levels that I think could have a huge impact on the pipeline.

BIRGENEAU: So on the Haas Diversity Research Center, Berkeley with its activists traditions, there's any difficulty encouraging people to be active. And so there will be an activism component of it. But frankly our goal here really was to make equity inclusion a serious academic subject with serious research involving economics and public health, et cetera, and to create a whole set of undergraduate and graduate courses in the area. The intent of the center more is to flush out the purely academic part of these issues, which then ultimately will translate into action.

In terms of K through 12, our educational disparities program is entirely focused on K through 12. And in parallel to that, we actually-- it's part of one of the things I've done at Berkeley is we established our own charter school. So we have our own K through 12 school, which is basically-- I don't want to call it a laboratory, because especially with African Americans, that's the worst thing you can do is to tell kids that they're a subject of academic study. I mean, we're trying to provide a really high quality education. But in the school, it is a living laboratory where we're trying to figure out how do you do K through 12 education properly in a way that's scalable, particularly oriented towards kids from Oakland and Richmond, who come from often challenging inner city environments.

MAATZ: I just wanted to address the academic piece real quickly. AAW, one of the things we really strive to do is to translate research into action. It's part of where we give our grants and look at the work that our fellows do. And so I'm really glad to know about this center because I'd be willing to bet there are some great-- there's some good research out there that I could turn into some pretty cool bills in terms of things to do. That's what I do.

But in terms of the K through 12 stuff, this is really important because this is where it all starts. One of the things that our report, Why so Few?-- this is what it looks like-- talks about is something called stereotype threat and how much it affects girls and boys performance. It's essentially the notion that the teachers biases are a self-fulfilling prophecy. If a teacher says that boys tend to do better on this test, boys are going to do better on that test than girls. And they're going to rate themselves better than girls.

But if you say everybody does the same. In other words, if you say, this is just a test and it doesn't matter based on gender. If you kind of act it's not going to be a difference, then there literally isn't a difference. Although boy still rate themselves higher. Boys always rate themselves higher on everything, which I find fascinating, because girls rate themselves lower. So there's this kind of very interesting dichotomy in terms of self-perceptions between girls and boys.

But I do want to caution, because one of the things that has kind of been sweeping the nation is the whole notion of single sex education. And AAW isn't against single sex education per se. We are against the current federal regulations that allow single sex education without any notice of civil rights laws or preserving civil rights of the kids. Because what's happening unfortunately in some of these schools is you have a science class that they decided to split by gender. And on a particular day the boys are going outside and digging in the dirt for worms, and the girls are standing inside and analyzing the composition of their makeup.

Now I got to tell you, on any given day, probably half the girls would rather go dig worms, and the boys would rather play with the makeup. So the reality is we can create these stereotypes and not even intend it. I guarantee you the teachers who came up with those lesson plans though they would be interesting, that they would learn something, and had no clue about kind of the misconceptions and stereotypes that they were perpetuating.