Brains, Minds, and Machines: Closing Remarks

TENENBAUM: I want to thank this excellent panel, and really everybody throughout the symposium for giving a broad range of perspectives on these different questions, and quite a deep set of perspectives. So whether you think that the study of AI and natural intelligence and minds and brains are deeply connected, or really just two parallel paths, I think it's good to note at the end, just to think both about how far we've come-- and our panelists here represent some of the best accomplishments, particularly on the industry side-- and how much of a gap there is.

So just to bring back some of the themes that several people made. So Amnon was talking about the discussion we had, the difference between what is a very impressive performance in, say, detecting pedestrians in the auto collision setting, and something that we can do all the time.

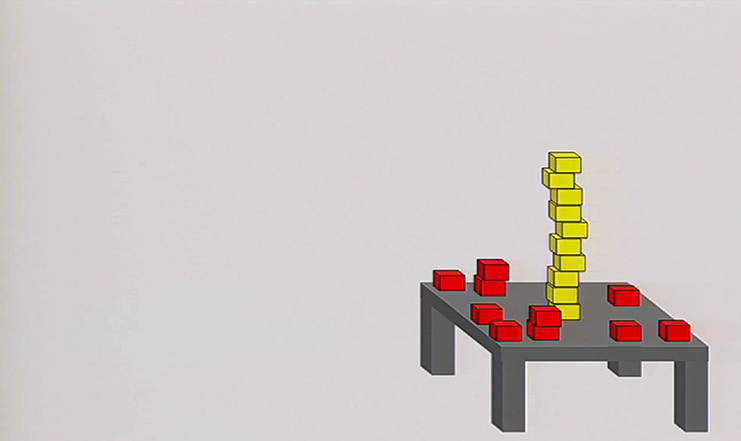

Take a natural crowd scene like this. This is a picture I snapped from the back of the room a few minutes ago. And you could go through here, and I could ask you to count all the people, and even though each person is maybe just a couple of pixels, in many cases, we could just go, doo, doo, one, doo, doo, doo, doo. And there are some uncertainties, so it would be probabilistic.

But think about the representations of space and objects and the understanding of human behavior. All that core knowledge business that, say, Lis Spelke was telling us about this morning, that really underlies your ability here. It's not just about learning the right classifiers from a big enough data set. At lease that would be my view.

And we could just continue. I'll use some of Google's intelligence here. If you search on crowd scenes, in any one of these scenes, you could pick out people, including ways that you maybe didn't think you'd train classifiers for. So like, in this rather ominous-looking scene, you can count the people, I guess, because they're wearing these hoods. At least to me, that looks ominous. Maybe it's not to others.

Or over here in this scene from a graduation, counting the people would mean detecting the purple parallelograms, basically, at least in some of the cases. Like, oh yeah, there's a person, there's a person, there's a person, there's a person, because we know about graduation, we know about the funny hats that people in our culture wear and so on.

So even a problem as simple as detecting people requires integrating a diverse range of knowledge, not just data, I would say.

Another striking success, triumph of industry AI-- of course, IBM's Watson thing-- but just let me just draw the contrast here, with all very much due respect for the accomplishments of the system and David's team and all that. What did it take to get this system to achieve world class level performance? I don't know exactly how you count at least 20 pH PhDs, probably more, working for several years, $100 million investment, and pretty much literally all the data in the world that that's there in machine readable format that you could download into the system.

But what did it take for you to learn Jeopardy the first time you did? Well, really just watching the show for a few minutes, even with the funny rules, you don't have to be told those rules, or if you're a little bit mystified, you might ask someone a question and they'll answer. Or somebody might explain the rule to you in a minute. But just a couple of minutes. Zero PhDs, zero dollars. But your basic human common sense is enough to not achieve, of course, world class expert performance, but to achieve competent performance in this and really an endless number of tasks.

I think game playing-- agreeing with Demis and others-- game playing is a great test bed for AI and a great way to understand just the incredible scope of what human intelligence is all about. So again, just to think about games as an inspiration for what we'd like to build, it's, of course, not just chess or Jeopardy or Go, but you know, here's all these classic board games that I played when I was a kid.

You know, your brain can learn to play any one of those games. And what does it take? Well, just read a few instructions. It doesn't take an extensive period of training from data. Or all these strategy games, we can learn those. We can do negotiation games, many of those. We can do various sports, Olympic games. It's all the same brain that's doing all of those things. Relationship games.

So intelligence is really about what underlies all of these things. And this kind of spirit, together with the sense that we have a whole range of tools, not just data, but certainly data, not just computing power, not just math, but all of these tools coming together that's been driving this intelligence initiative that was, for Tommy and I, our inspiration in coming together with Irena to drive this symposium.

And it's just a very exciting time for MIT to see all these different units across the Institute, really, with the lead being taken, at least so far, from the cognitive sciences and the neurosciences and the computer science and AI lab. But really, this is a much broader initiative, and we're excited to have really anybody who wants to be a part of it, we're excited for you to be joining our team.

So I'll just leave us with some of the real questions that have come up in informal discussions, or more formally last night. First of all, who's going to do this work, and how long is it going to take? Well, all of you, like I said, are invited to join us. And as far as how long it's going to take, we've learned that that's not a question you should ask. Fortunately, this is the kind of optimism that doesn't require, actually, that kind of timeline.

Who's going to pay for it? As Terry said last night, that is the key question, and how much will it cost? Well, Kobi signed up for 10 post-doc grants, and we've got a list out there for the rest of you, and Elizabeth is taking down your numbers.

But just as seriously-- I was about to say more seriously, but that's fully serious, of course-- just as seriously, we are excited to acknowledge a number of people who, maybe without exactly knowing it-- in some cases knowing it-- have provided some preliminary funding for this effort, both coming from industry and various government agencies, have been just giving grants for various kind of exciting interdisciplinary integrative intelligence projects across these different units.

And recognize, as Terry said last night, that it's going to take a lot more, not just at MIT but at many other institutions. So it's exciting, but big project to be trying to tackle.

And lastly, just on behalf of the other organizers, I want to acknowledge a few key people. First, I want to acknowledge Tommy and Irena. I would say, to be perfectly honest, Tommy, of the three of us, did the vast majority of the work, so I personally want to thank him for that.

[APPLAUSE]

But that's the vast majority of the work that the three of us did. I would say the actual vast majority of the actual work was done by Kathleen Sullivan. Where's Kathleen?

[APPLAUSE]

Is Kathleen here? So she can-- I don't see her. OK. Where is she? Did she stand up? OK, great. Kathleen is-- thanks. Kathleen is the administrator in Tommy's CBCL group, and she really just brought everything together. All of you who participated know that.

Many other students and post-docs and staff, again, largely in Tommy's group, played key roles. And I would also like to thank MIT as an institution from the top down, meaning from the president, Susan Hockfield, and her office, all the way down both in encouraging the symposium and the intelligence initiative, and all the way across. All the five schools of MIT have provided both encouragement and funding for these efforts that we're doing here, and it's quite exciting.

And of course, we wouldn't have any symposium and we wouldn't have research without the speakers and the participants, so a big hand to all of them. Thank you.