Economics and Finance Symposium - Keynote Address: The Future of Finance

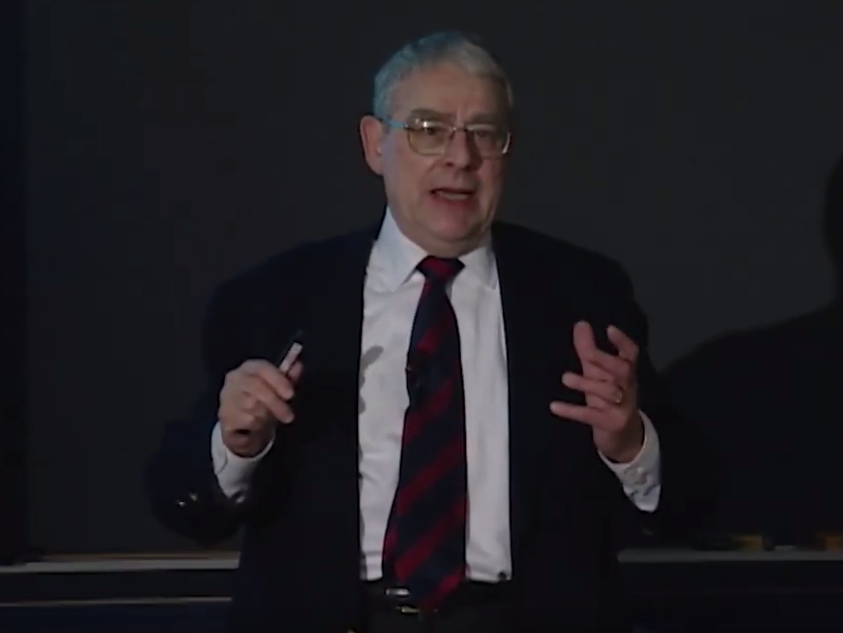

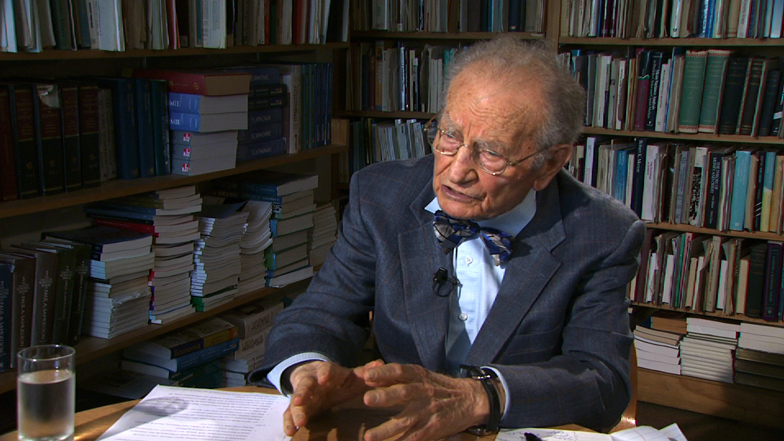

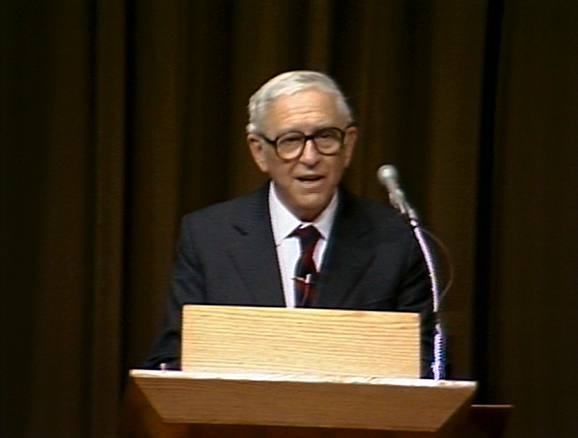

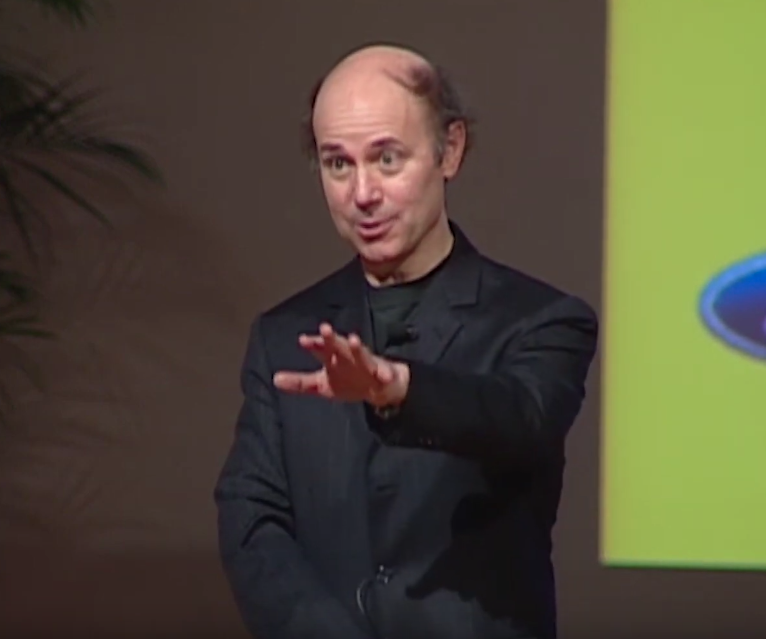

COX: It's an honor for me to be able to say a few words today about Bob Merton. Some of you have already met Bob in the early morning session, but many haven't. So I'd like to start at the beginning.

Bob was born in New York, the son of the great sociologist Robert King Merton. And he grew up in a small suburban town just outside the city. There he had a quintessentially All-American childhood, playing varsity football and building and racing dragsters.

The two things that I always dreamed about doing, but never had the skill to accomplish. One thing, however, foreshadowed his future career. According to Bob, in childhood games he often pretended to be a banker.

Bob went on to study engineering at Columbia where his father taught for many years. And after graduating, he enrolled in the doctoral program in applied math at Cal Tech. Fortunately for all of us, he soon decided that his heart was really in economics. So in 1967, he moved to the economics department doctoral program at MIT where he formed a close and fruitful tie with Paul Samuelson.

Bob joined the finance faculty at MIT in 1970. Bob's years as a graduate student and a young faculty member were filled with remarkably brilliant insights. It's no exaggeration to say that during this time he revolutionized major parts of finance.

Earlier, Harry Markowitz had shown how to construct optimal investment portfolios. And Bill Sharpe had shown the equilibrium implications of Markowitz's work. Both won Nobel prizes for their research.

But as important as their ideas were, they were set in a static and timeless setting. And Bob was the first to realize that those key results would be fundamentally different in a dynamic environment where investment opportunities were constantly changing.

In two landmark papers he developed a truly intertemporal theory of portfolio selection and asset pricing. At the same time, Bob was doing foundational work on options and their applications to corporate securities.

His work there formed the basis of countless subsequent academic articles. And for their work on options, he and Myron Scholes received the Nobel Prize in 1997. Bob has head as great an impact on industry as he has on academia.

The work that he, Myron and Fischer Black did on options can be applied to the valuation and hedging of almost any security. As such, their ideas formed the intellectual basis for the modern derivatives industry, both on exchanges and an in over the counter markets.

Furthermore, many non-financial companies now use option pricing methodology to judge the value of flexibility in their physical investment projects. In fact, every year, new applications are developed for the contingent claims framework that Bob pioneered.

And later, Bob's research turned to financial innovation and the way that financial institutions change over time. And partly as a result of this new focus, Bob moved down the street to Harvard in 1988.

There he was for many years a university professor, Harvard's highest honor. To our great joy, this past summer Bob finally decided to come back home to MIT. So now I'd like to introduce to you our newest faculty member and your Keynote speaker, Bob Merton.

MERTON: Thank you, John for that very nice introduction. And this is quite a crowd. I can't remember when the last time I was in Rockwell Cage, but I never imagined speaking here. Well, I hope that all of you were able to be in the morning sessions, because some of what I was planning to talk about was very well covered.

In fact, covered better than I could do. And that gives me a little more time for other things. And you a little less time to have to listen to me as a captive audience. Finance is important to all of us.

A well functioning financial system, including its legal and accounting components, is a key driver for realizing the long term growth and development potential of an economy. This conclusion emerges from a variety of studies, including cross country comparisons, firm level studies, time series research, and econometric investigations using panel techniques.

A number of economic historians have included that those regions, be they cities, states, or countries, that developed the relatively more sophisticated and well functioning financial systems were the ones there were also the subsequent leaders in economic development of their times.

Now for nearly four decades, financial innovation has been a central force driving the global financial system toward greater efficiency with considerable economic benefit having accrued from those changes. The scientific breakthroughs in finance in this period were both shaped, and were shaped by, the extraordinary innovation in finance practice that expanded opportunities for risk sharing, lowering transaction costs, and reducing information and agency costs.

Today, no major financial institution in the world, and this includes all the central banks, can function without the computer-based mathematical models of modern financial science, and the myriad of derivative contracts and markets used to extract price, and risk discovery information, as well as to execute risk transfer transactions.

But as I need hardly say, the global financial crisis of 2008 to 2009 of the magnitude and scope not seen in nearly 80 years, which at least some attribute to the cumulative changes in the financial system brought about by financial innovations, particularly those involving derivatives and mathematical models.

Now in determining the causes of the financial crisis, and we had that discussed yesterday and again touched on this morning. I actually believe that the pathological data necessary in the gathering is not complete. That doesn't mean we don't know pieces and parts, but even in today's newspaper you saw the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission was just a major Times story.

And you may recall, if you saw it, what the conclusions were. They depended on who you read. This is after collecting the data. Just as an aside, and please hear this in a sense of humor, not as criticism. But it is rather interesting that there is a sort of process to imagine that Dodd-Frank was passed last summer presumably as a result of the financial crisis.

And the investigation to determine what caused the crisis was completed several months later after it was passed. Something to think about. But in any case, I think there are many plausible hypotheses, but they are still hypotheses.

What I'm pretty confident about, though, that when we do come to have a better understanding of the whole of the interactions, it will not be some single item. As we recall perhaps in the story with Feynman and the sad occurrence of the Challenger disaster, which by coincidence happened exactly 24 years ago today.

In which you may recall when he dropped the O-ring into the ice glass, or you saw pictures of it, and when he took it out after all discussions snapped. And that's what happened. Now we know there was a few other things besides that, but it was very dramatic.

I don't think we will find that here. But I'm not going to focus on the crisis, because we've heard so much about it. They're clear, there were fools and knaves, but it should also be clear that there were many structural elements. Elements that would have happened even if people were well behaved, and well informed.

And in looking to the future and how we can, if not avoid such crises, at least mitigate them or be prepared for them, it's important to know that it isn't just a matter of bad behavior or foolish behavior, but, indeed, we have embedded in our systems structural risks that are inherent.

And in many cases ones there's very little we can do to mitigate but only be prepared for. Now on the crisis, I have a couple little remarks. There's going to be no continuity to them, just bullet points. Because I really don't want to stay on the crisis.

But on some of the issues involving the crisis, I think, you'll see that in many cases, it was old finance, not modern finance. I have in mind, for example, in the case of AIG, you are all aware, where AIG, unlike what I thought all the big firms were doing did not have two way mark to mark collateral from the beginning of its positions, its derivative positions.

So unlike Lehman, which we know the disaster there, which did because it was lower rated. And I thought everyone did. So I just wasn't knowledgeable. I said, how can we be operating without it? But apparently, it was seen to be OK to use the old fashioned idea of a credit rating, a AAA rating guarantee, as a substitute for collateral.

And as a consequence, really no controls on the magnitude of the positions. After all, if you don't have to post anything, it's hard to control it. But it's important to remember that. Another one is efficient markets.

Now one doesn't have to believe in that religion completely to accept the principal from which it's derived. Namely, there's no free lunch. So in the case of Blackstone banks in Germany buying AAA paper in US real estate, which they were criticised ex post, I give them a pass because a AAA is supposed to mean that you don't have to know what's going on under the hood.

But then I've got to give them a fail. For what? The yields on those AAAs were based financing rate plus 250 basis points, 2.5% That is not consistent with a AAA number. Now once in a while, like the $50 bill on the floor you find, a trade like that may come up.

But if it's available every week in volume, something is inconsistent. And it's the lack of saying, there is no free lunch. We've got to understand why. And if we don't understand why, stay away from it. That I think we'll also find was a part of the cause.

Another item is plumbing. I was really surprised. I mean, I confess. I didn't realize how much it was that documentation and such would cause what's called complexity. Because while a millions securities are called complex, as Stu Myers said earlier this morning, compared to be regular firm, special SPV structures and so forth were not complicated.

But they are consummate if you can't get the documentation. So one other last point and then I'll move on to what I really want to talk about, and that is innovation itself. Someone said, I can't recall who it was, maybe they were just having a joke. Something about the only innovation they remember having happened in recent times of any worth and finance was the ATM.

No point debating it, but I can think of there's two or three just come to mind. For one, household finance. If you look at what we taught, many of you were in the classes. We taught about holding well diversified portfolios, and keeping your cost low, and clearly individual trading in individual stocks, except for consumption purposes. Or because they're forced to because they're entrepreneurs and they're intimately engaged in the business has got to be suboptimal.

And yet that's what individuals did almost exclusively at the beginning of this period that I talk about. Today, I think it's fair to say they may still be speculating or doing things that we might not think are totally optional, but they're doing it better in the sense, now they're using mutual funds or ETFs, or at least they have a diversified position.

And many more people do get reasonably efficient exposures to the equity markets than they did in the 1950s or '60s. And I had to point that out. The second one is, of course, the national mortgage market.

I'm old enough to actually live through some of the good old days. And I can tell you that every time [? recq ?] came in and you couldn't get money, that had a rather negative impact on housing. The idea that we have mortgages available, at least we used to, I won't comment on them most recently.

But is a manifestation of that. It created a competition. And it was again mentioned this morning. It spread the risks of those mortgages around rather than leaving them in the local holders.

And then, of course, as close to as the many other examples are the banks. What's the classic risk in a traditional simple bank. I say simple, it makes loans and takes deposits. It's always an interest rate mismatch.

It's creates huge interest rate risk. That interest rate risk does not add value to the bank's business. Anybody can speculate in interest rates. And if the bank has a real skill set for forecasting interest rates, it's wasting its time to do that with customer's deposits, as well as it should just do that as an asset management and get better compensated.

And so it's clear it's a risk, a big one the banks, in their traditional roles, had to bear. And we don't even think about it anymore, have no need to bear, so that if they do so, they do it so it's their own choice.

Well I won't go on. I want to talk about the future. Looking future finance. This title, I'll take responsibility for, but was a little bit short. But think of it more as observations on the future of finance. And actually observations on the future financial engineering, so we get it down to a more tractable scale.

Now, in looking to the future, there are two areas. One is basic research. And there, actually, I'm not going to say very much. I may come back to it if I have time, and you have willingness, because we have many venues to say this. And I was thinking on this occasion, it would be more appropriate to talk about the applied uses of finance in the future.

Those that lean on, or make use of, what has been developed and taught here and other universities, but which is the sort of, what we would call, the financial engineering. And then I was asking myself, well how might I go about doing that?

And I thought about it, and I said, well rather than talk about it in generalities, I'm going to do a case study. But not the ordinary kind of case study. I saw a bunch of people about to leave the room, including John Cox, who introduced me.

But don't you fear about that, this is a live case study. And what I'm going to do is take a problem, a global problem which is quite substantial. One that we have to address, and that whether or not the financial crisis is on the front page is not going away, and, in fact, this is back on the front page.

And ask ourselves the question, how do we go about attacking that problem? And treat it a financial engineering problem, go through it with you, and see if, in some exemplifying way, this example shows why financial engineering, and finance in general, has an important future. And why we don't have the option to go back to the 1930s.

I have no objection, and I to be clear about putting restrictions on what institutions can do and can't do. And if we want to keep depositories institutions from doing other activities, my many time colleague, coauthor Zvi Bodie and I wrote about that probably 20 years ago.

And so that's not that. But going back to Glass-Steagall literally doesn't make sense. It's no different than when you have the case of saying, let's put get rid of Google, let's get rid of Facebook. I saw Hal jump. I said don't worry.

I don't think there's much chance. It's the same thing. The world has changed. We can't go back. So let's talk about what we should do going forward. With that as an introduction, let me tell you about the problem. The problem is that of retirement.

And I'm going to make it more focused. It's dealing with the retirement part of the life cycle, to tell you that if you think about retirement the way it's normally talked about. Over in Europe it's referred to the three pillars, here in the States it's more folksy, it's called the three legged stool.

But basically, every way you look at it, the three parts that make up financing retirement are government, in our case social security, employer provided pension plans, and personal saving. In the last 10 years, particularly, the leg of the stool that has been most in shock, and is the biggest change coming forward is the employer plans.

And it began, I believe, beginning in 2000 and 2002 where you had world stock markets decline substantially. At the same time interest rates declined substantially. And as a consequence, defined benefit plans, the mainstream pension in which the benefits provided to pensioners are fixed in advance and the issuer, in this case the company, guarantees it.

As a result, the falling interest rate made liabilities rise. Falling stock markets, assets fall. And some of the weakest companies in the industries, such as steels and airlines actually went bankrupt as a consequence. But more to the point, it became pretty clear how risky and expensive these plans were.

And in my own view, the watershed was January 2006 when IBM, known to be an employee centric company, highly profitable and with an over-funded plan, nevertheless capped its defined benefit plan for existing employees. No more.

And after that, many other companies followed. So, this created a challenge because employers are not getting out of the role of providing benefits. So what did they do to replace this? Now this is a challenge, but it's also an opportunity. Every such challenge has that.

The natural candidate, and many of you I have these plans, you all must be aware of them by now, are defined contribution plans. By their very name, you know what you put in, but you don't know what you're getting out.

It depends on what investment experience you have. By going to those plans, it solves sponsor's problems of unbound or hard to estimate exposures and cost. But in the process has made things extremely complicated for all of us. All the people who need retirement.

It is a much more complicated system. It adds individuals, you and I, to make decisions we've never had to make in the past, don't know how to do now, and won't be able to do even with education going forward.

We have to solve a very complex optimization problem that John was alluding to. What is it? We get contributions coming in, typically as a percentage of our salary while we work. And what has to come out at the other end? A pension.

A pension adequate for us to live in the style that we would like to, and expect to be able to do. And that's over many years with lots of uncertainty. The idea of asking each individual to be responsible for that analysis, decision and implementation isn't remotely close to optimal.

So what could one do as an alternative? So I want to take you through at least one pass of this and I hope in the process exemplify all the different parts of financial engineering and why we need this.

So if you're going to start out with a new pension plan, you're going to design it, and go back to scratch, what's the first thing you need?

Before you can optimize, before you can design, what do you need? A goal. What's the goal? You got to find out where you want to go before you start going. So, if you have to come up a goal, and remember this is for very specifically, this is not probably for most of you, thank goodness.

But this is for most people do not have financial advisers, do not have a lot of extra money. They're doing fine, they're working. Not talking about people who don't have jobs. But this is for people who don't have advisors and don't have the luxury of having themselves psychoanalyzed periodically to find out what they want.

So you have to come up with a goal that fits most people most of the time. And the one that seems sensible to me anyway was to say that people would like to sustain the standard of living in retirement that they enjoyed in the latter part of their work life.

You know, you're young group. But when you get there, you've gotten pretty used to how you're living, and you wouldn't mind living better, but you sure don't want to live worse. And so that was the starting goal.

And you say, OK standard of living. How do we define that in some way that we could actually execute? Now this isn't about how you feel philosophically or emotionally. I can't do anything about this. We mean your economic standard of living. But how do you define that?

Well, it's a common sense thing. You need to come up with some measures, and first you say we broke it down to three areas. One is medical, housing, and then general consumption. You could have 20 categories, but those three seem to balance between complexity and difficulty, and getting the essence of the point.

I'm only going to talk about general consumption. Now, how do you define what you need in retirement? Well here I'll call on Jane Austen to help us out. Has anyone read Jane Austen. There's somebody out there. He can check the quote.

As you may recall, when she was writing about English life, she didn't write about the big things, in the sense of what governments are doing. She was interested in people, and particularly she often wrote about men, and whether they were appropriate for her or her friends.

And so when she was evaluating let's say, Mr. Darcy, she didn't say he was worth 100,000, she said he's worth $5,000 a year. And I think if you start to talk about our standard of living, how do we think about that? Is it a certain amount of money? No.

It's a flow per year. We have a standard of living. I can live at this standard of living if my income is thus, or the sources I have. So here's the goal we came up with. The goal was for general consumption in retirement that what people would like to have is a stream of income in retirement protected for inflation, so it's really dealing with standard of living, not hiding your deteriorating standard of living.

For life, so you don't have to worry how long. If you live like the Good Book said to 120, great. And if you don't, you don't need it. So for life, the level protected for inflation. So that's the goal. How much you need, well, that's part of the process.

The typical way to do that is you estimate based on what people are making in the latter part of their work life, that their standard of living, if they've been living on that, will be roughly dictated by that. So it's an object. So we look for what's called a replacement ratio.

What fraction of my earnings in the latter part of my work life would I need to sustain that standard of living that I'm enjoying at that time? It may be very high, not so high, or lower. But whatever it is, what will I need?

And that became the target. So it's a little more complex. It's not a certain amount of money. Not just a certain amount of money or income for retirement, but an income as a function of how much you've been earning in the latter part of your work life.

OK. So that's the goal. Now, before we do anything else, I'm now going to, for those of you who were in my class, remember I always used hard copy. Nothing's changed, so there's at least a 50-50 chance I'll push this the wrong way.

I did get it right. Now, whether I get it right the rest, I don't know. But here's what we did. So the first thing you do is you set up for target. And I kind of wrote this down. Now if we have this target income, then, first of all, how do we get there? Well, that's a complex problem how to get there.

But whatever we do, we're trying to get to this level of income. Is my voice changing as I walk around? OK, so we better stand here. All right. Is this better? So what we have is a target way. So what you might think of is the first thing you can tell people is, here's their level of income, really as a replacement level, but we don't tell them that.

But here's a level of income that you should desire for this goal. And then, we tell them another thing. And I'll tell you why in a minute. We tell them what a minimum risk level of income is for that period. And that's another target. What's minimum risk mean?

It means not guaranteed, but it means a level of income that you do everything that you know how to do with all the technology you have, and the focus of investment to get you that amount of income. So it's what you might call the safest you can do within what's feasible.

All right, so you have desired, minimum. OK, now suppose I tell you next I'm going to tell you, given some other conditions, what your chances are of making that desired. You could think of it, we're here at MIT, as a probability, right?

Well, let's say it says 60% chance. If you think of that as a test score, how would you like that on your test? Maybe not so good. It's kind of a D minus. Now, actually in the UK, they say that's pretty good. So there are cultural differences.

But I think in Holland, or here in the US, people would think of a 60% chance of getting there is not exactly what they had in mind. So, what can they do about that? Well, if you want to improve your chances of getting there, I can think of only three ways.

I'm going to look over there at Ben and others who are sitting at the table. If you have a fourth way, well I'll give you a fourth one, but it's not a real one. But if you have a fourth way, we have this on tape, you'll get full credit for it because you help the world.

But the only three ways I can think of to improve your chances of getting to the goal are save more, work longer, or take more risk. Someone said, be lucky. That's the fourth one, but I don't know how to do that.

So if those are the three things, then what we want to do is say, give people choices. So this isn't like it. But only meaningful choices. I'm trying to contrast, I assume most of you know what a typical DC plan is. You get this thing that shows you a risk return frontier, a bunch of funds you can buy, shows how much money, a distribution of how much you'll accumulate when you retire in wealth. And a whole bunch of other things.

And often will ask you questions about your risk preferences. Do you prefer this gamble or that? And frequently they'll also ask you eventually how much mint cap back equities in Europe you want to hold in your portfolio. There's a lot of discussion of asset allocation.

So keep that in mind. I'm not going to go through it, because I know most all of you have seen it in some fashion. And so here's the thing. We had desire, minimum risk, and the only three ways we can improve that, and you've agreed, or at least you didn't shout some fourth one, are either by saving more, working longer, or taking more risks.

So what else do we add? We had it on the same little one screen. How much are you saving now, this is contributions. When do you plan to retire? So four items. One screen, nothing else. And the little score card tells you what your chances are.

Now, suppose you want to improve your score. What could you do? You could increase the amount you save. So you move a little slider and up it goes. I just give this as an example. You understand there's no one optimal, but I'm using an example to show you how you think, and how you put it together.

And you move it up, and guess what happens? The score goes up. After a while, you get used to it. You move it a little bit, score moves, and you get an idea of how those two things work together. So like driving a car. When you first learned to drive, you didn't know much to turn the wheel, or how hard to hit the brake, or in the days of the clutch, how much to lay it out.

But eventually you learn. Even with a high school education you play around with it. All right. So you put up a little bit, it gets a little better. So maybe your 60 gets to 67 or 68. And you say, well what if I worked a little longer, because I can't save any more right now.

So you put it up a couple of years, and the thing goes way up again. And you say OK. And then you say, no I don't want to work that long. And put it back down. So now would you still want to get higher, what else can you do?

What was the third thing I mentioned to you? Take more risk. So how can you do that? Remember that minimum risk? You lower it. People can relate to that because they say, I'm trying to get this much, I have a very, very good chance of getting this much, and if I lower that, I'm taking more risk.

What do you think happens? When you're willing to do that, you get a better chance of getting where you're going. Now what's the point of all of this? I mean you're saying, why am I taking you through this? Let's go back to the principles.

I mean, if you agree with all the steps. I've taken you through all these three things. These are ways for people to make choices that are meaningful. Why are they meaningful? Because if you put that slider up, and you push the right button twice, your paycheck is smaller next month.

That's not a hypothetical. And if the thought of working another two years doesn't get you thrilled, then that's a trade off, as well. And, of course, taking more risk. That's it. That's the design. That's the front end.

Doesn't get much simpler. So it gives people a way to react. And you think of it as like a doctor's, when you go in for your annual checkup. And I go in for mine, I'm hoping my doctor will say to me, wow, you're all your numbers are great. In fact, if we didn't know better, we'd think you were 10 years younger. That's what I want to hear.

But suppose that's not true. I mean, my doctor could still tell me that, right? But then what's the point going for the check up? So even though I want to hear that, I really want to hear if something wrong. So if they say to me, well Mr. Merton, your cholesterol is 300. That's not good.

But what they then tell you is something you can do about it. You can exercise, you can change your diet, you can take statins, Lipitor and so forth. So they tell you have a problem, but then they tell you what you can do about it. It's exactly the same thing here. If you don't like what your retirement looks like, here are choices that you can make.

And if you don't, you don't. But I've purposely made it very simple. That's the end of all this design as far as the user sees it. It doesn't get any simpler. Anyone who's going to all these websites and they've got diagrams and everything, I mean, that's fine. If you want to do it.

It strikes me very much like an automobile. When you're buying a car. You care about gasoline mileage, you care about zero to 60 speed, comfort. So someone says, you know, I'm selling my car I've got a 9.0 to one compression ratio. And Myron's selling a care in competition and he says, mine's got 9.4 to one compression ratio.

Now you're smart people. You know that it must be better to have a higher compression ratio. But how many people in the room-- we're at MIT, remember, not in a random place-- how many people in room can tell me by increasing the compression ratio by 4/10, from nine to 9.4, how much more gas mileage I will get, and how much faster my car will go zero to 60.

I suspect there are not many. And that's what investing, a lot of the advice that you get, if you've ever think about it. And this is what we're asking not just MIT people, or people who enjoy doing this, the direction we're going in is the solution for retirement.

Not just here in the States. Not just in the Anglo-Saxon, UK and the States, but in the continent and other places. Everywhere is going for it. Why is this a problem? Another problem, I'll tell you where else it's coming from. We're back in the newspapers again.

Anybody notice anything on municipal pensions? Has anyone seen that in the paper? Now, some reasonably sensible people have estimated the underfunding for municipalities and states at $3 trillion.

I know we all get used to a trillion here, a trillion there. $3 trillion is a lot of money. And we're going to have to solve it. I don't know. I look at Jim Porterba, I assume he's going to advise the government as to how we're going to fix this, at least get them to $3 trillion.

But after it's fixed, my guess is we're not going to have a big appetite for going back to DB plans for municipal employees. That would be suicide, right? I mean $3 trillion, that makes the S&L crisis look like nothing.

So this means, probably, we're going to have to deal with all those employees in those systems as well. And the question is, do we just go in do it using historical method, or do we actually try to solve the problem in a sensible way.

Now I went back to first principle. Now let me show you one of the problems with this. First of all, with this simplicity, how do you solve this complex problem? Well, the complexity is all under the hood, just like your car.

You get in your car and you push that button or if you have a whatever and you drive it, but what's going on underneath is very complex. And what's the difference here from what the traditional DC does, which is to tell you to make all these complex decisions, is all the complexity is put under the hood to make it easy for the user.

Paradoxically, that creates the paradox that makes it much more complex for the producer. Anybody can give advice. You go pass series 70-XYZ exams, you can give advice from your garage.

It's quite another thing to deliver a totally finished solution, a car. Where it's simple to user and complex. for the user. And all of what's going on with that probability that they see is there's a huge amount of dynamic optimization going on because what we're really giving them is the frontier.

We're optimizing given the best we know how to do it. That doesn't mean someone else can't do it better. But you understand that's all taken care of. And when I say we, it's the hypothetical we. Whoever's doing this, solving this problem.

And the point here is simplicity. The point is that to do this it's very complicated, and in particular, what is one of the problems I want to show you how big a change this simple is with the next slide.

First, I've listed a few things of which you would want to have in the rest design. It has to be an integrated solution, which means it uses your social security, all of the other sources of retirement, because it doesn't do me any good to optimize on one thing.

It has to be robust, which means that the individual may never make a choice, it has still work. All right, and that's a design criterion, which is pretty tricky, because you have to make something where you're deciding for people who won't even answer an email. They won't even tell you. They barely tell you their gender.

It has to communicate clearly, as I met with the medical example. The meaning of choices, but it also has to fit the constraint. That's why we did it as a SC that the sponsor has to have limited risk.

OK, but now let me show you what the problem is. First problem. You all agreed with me that the goal was income for life. Have I lost you? All right. You all agree with me the goal for us is income for life. I feel so constrained here, but that's OK. I'll stop sooner.

So suppose you had a 45-year-old who is retiring at 65 and [INAUDIBLE], that person has so much money accumulated already that they actually could buy what they wanted for retirement now and take no risk.

Now that's just for illustrative purposes. I don't think we find too many of those, but if you did what would they buy? What's the risk free asset is what we would say in our parlance. It's a life annuity, a stream of income at the right level beginning 20 years from now, and paying that person for life.

So it's a fixed income instrument, has longevity in it, because it's for life. But it doesn't even start paying for 20 years. Do you realize that that's the safe thing. You buy that, no matter what happens, you've got it as long as it's the right issue.

Now, let me show you what the current rules and regulations and what people are used to seeing. All of you, you have mutual fund accounts, whether they're retirement or not. Don't you get your NAV or net asset value, and how it's changed, or maybe you even look it up, but they very conveniently make it for you.

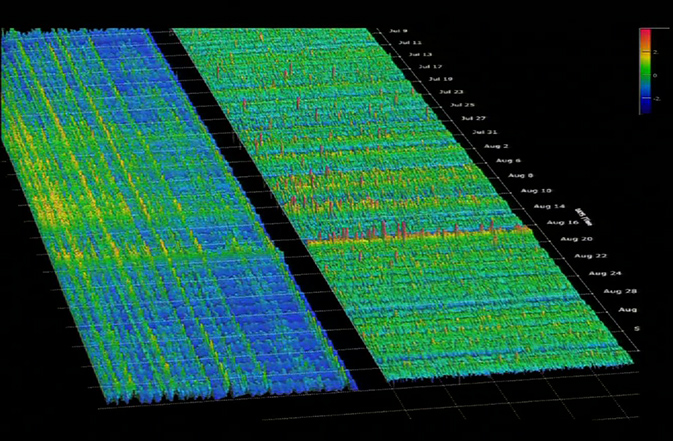

What I've done on this screen is create first a security, which we call an annuity unit. All it is a security that I just described. It starts paying in 20 years. It's inflation protected. It's a level payment for the appropriate lifetime.

OK, nobody understand that? It's like a bond. Now on the left, that's the monthly returns you would have gotten from 2003 to 2010 watching the monthly returns. Remember, you have no financial advisor. You open your account, and what do you see as a user?

You've been told this is a risk free asset. What does that picture look like? Doe that look risky to you? This is the value of your portfolio every month. I think it doesn't look at all that way. The problem is that the information is being conveyed in the wrong units.

It's conveying in current dollars or euros. What it really wants to convey it in is the thing that matters to you, which is annuity units. Well what does an annuity unit look like as priced in terms of an annuity unit.

One annuity unit exchanges always for one annuity unit. So you see, if you put it in the right units, you get the graph on the right side, which is the common sense. This equivalent to a currency change. The way some of you may help you, it's like you were investing for someone in dollars here in the States, your company is investing for someone, but they happen to be Japanese investors who care about yen.

And so would you give them dollar returns so they know how they did with what's matters? No. You have to convert it. Well we're converting it to units that matter to people. So I show you this to see how different the information is.

Now let me show you one other familiar asset. US 30-day treasury bills. On the left, you see for those seven years hardly any variation. The principal amounts are always protected and very little variation. Safe. Isn't that how we always think of a treasury bill? Safe.

But in terms of the goal, the thing that you all at least with your faces, even if you didn't physically agreed with me was that the goal, you see the risk it is? It's an incredibly risky asset. So what I want to see is this is a first order effect. This is not round off.

This is about the idea if you use the wrong units to measure and communicate. First you have to communicate with people. So, it's very hard for people to understand. Secondly, if you're managing this, we talked about risk, if you're measuring the risk incorrectly, how can you possibly manage it correctly?

And now I'll use this to show you one more step. If you create, for those who know, a risk return frontier, you know expected return versus volatility, I plotted the three on the left for the usual way. And you can see annuity units are almost as risky as common stocks, that's what MSCI is. All right, and T-bills are not low risk.

Now look at it in the proper units. Annuities are risk free by construction. T-bills are very risky, and stocks are sort of in the same, qualitatively, the same place. So the point being that the risk return frontier is wrong, and that's the bad news. If you really are serious about solving the problem, then if we do it by our traditional techniques, we're very far removed.

Now, how could we have done this? We could have used a model that I did several years ago, in which you have-- I have trouble with my fingers. These are two dimensions. Three dimensions, we go to four, I'm out of it.

So you could add it as the traditional frontier dollars of return versus volatility in dollars, and then interest rate risk. But, of course, the risk here that's going on is both real interest rates, inflation, and longevity, all of which are not small risks, particularly real rates.

And so what happens is that this way allows you to do what? It allows you to represent things exactly in the kind of frontier that people are used to using by making this transformation. And that's important in the practical engineering solution. Why? Because there's a multi-- I don't know how many billion industry, of pension consultants, portfolio managers, and others, who have model after model after model of this type.

If you go to them and say, we want to change the way we do things. By the way, everybody is going to have to scrap their models, I don't think you're probably going to get much of an uptake. And so it's this kind of thing. I know you say, why am I going through-- I'm trying to show you, by example, all the things you have to deal with.

Now let me give you another problem here. Let's go back a slide just for a second. Remember, this was the risk free asset? Regulators are talking about, in some cases have already put in, to make people safer they'll put in a principal floor, or a minimum guarantee return.

But where do they measure it for? They measure it for respective value. All right? Look at the left side. That's a value measure. I can't put this person in a risk free asset, because if I do I'm very likely to violate the regulation. Next slide? No, no. The T-bills.

OK, well the T-bills are safe. Yeah, yes. But that's why I'm saying. I just wanted you to see the annuity one was going like this. And if we put a line there, it would violate the principle. That's why I showed you the first one.

So I'm just quickly saying, one, this is an order one effect. Two, there are ways to deal with it in the real world without forcing the industry completely to change. So it's feasible to do this sort of thing. And three, all the regulations are right now being written in the Department of Labor, in the European Commission, and the various other entities, people are putting up ideas that sound very sensible.

Let's put a minimum return in. Let's put a principle guarantee in. It all sounds very good, but if they're not understood what they're doing in terms of the real objectives, they could actually keep us from doing the right thing. And so that's the essence of this piece.

The last part I'll show you about this that changed the engineering. Again, not because it's better. It's better for, we think, the goal. What we've done is I showed you with the kind of a bell shaped curve. Don't take it literally.

That's the typical generic portfolio end of period value kind of thing where they say we'll get you with 95% or 90% or more. And if you look at the blue line, you'll see what we've done in optimization is focus on the goal.

And so we maximize the chances of the goal subject to risk constraints. And so what are we doing? We've transformed the distribution so that the right side tail that you get in a traditional DC you don't get. But you also don't get the left tail.

But you use that right tail to improve your chances of getting the goal. So, I'm not saying one is better in the other. It depends the right tool for the right job. The point is that when you truly optimize and don't do things, you can significantly improve the chances of success. And what we need to do for this group of people, for all of us, for the millions of people that don't have extra money, we get the most out of their assets.

We've got to deliver a simple, easy to use and if they don't use it, still gets them their solution, which gets the most for what they can do. The technical problems in this, they're the things that we heard talked about this morning.

You have to have dynamic strategies that are optimizations. You use all the tools that you're legally allowed to use to implement this. You have to be very, very careful, because these things really do work. And there's a lot to design.

But I wanted to just show you this as a way of taking you through and saying, here's a big problem that's not going away. It's here. And maybe you believe, there are people out there who believe, that you can solve this problem well using a simple bond market, bank loans, and a simple equity market.

And get rid of all the complexity and go back to the one 1950, or '30 or '60 or '80, but you'd be throwing away an awful lot of what you can do because the market proven technologies that people have developed and used in firms represented in the tables here and over here, can be applied here to do a much better job for people.

And if you think of the importance of this, I think that this is just one example, and one that's very important to me as I share it with you. But it's only one of an example of why the idea of not using all the financial technology we can put together, all the optimization, taking advantage of computations.

And, by the way, if you may not have realized it, but this has a lot of behavioral finance in it. Because the way that thing was designed to get people what they look at what they don't look at was precisely so that they can understand it and use it.

So they're really using all the disciplines, the modern disciplines, of finance to try to come up with the best solution. And I guess I've grown now gone past your lunch, and mine. I want to thank you for listening to me.

I want to say that it's been a wonderful time in this field, and I'm really happy to be back here at MIT. And I want to thank you all for coming to lunch. I know it was a lunch, but you did pay for it, I think. And maybe you didn't, I don't know.

But in any case, thank you all. And I'll take questions if there are any.

AUDIENCE: Saying, well, I don't want to give up more money, and I don't want to give up time. I'll just turn risk to the absolute top.

MERTON: Well that's a very good. Did everybody hear the question? The question was, what if people don't want to save anymore, don't want to work any longer, and want to put risk to the top? Of course, we could legislate what we're allowed to do.

First, there's limits to what calling risk to the top is, because there are only so many things you're permitted to do, anyway. So it's not an unbounded risk. You can't leverage, for example, in these accounts.

But the answer is, you've got to decide. If you're going to have plans where people have choice, then you can tell them, but in the end, it's their choice. They're getting feedback. They understand what they're doing. They're adults.

If you don't like that, you can go back. But it's not an answer to go back to a DB plan where you designate everything, because they won't work. So the answer is if people will not save more, what do you do about the person with 300 cholesterol if they won't exercise, they want to change their diet, and they won't take statins?

Eventually, if you tell them everything and you keep reminding him, that's all you can do under this structure until you can force people to do what they do.

AUDIENCE: OK. Is your analysis the same? Case one, 5% of the American population adopts the plan. Case two, 100% of the American population adopts the plan.

MERTON: I think the analysis is the same. Maybe you could clarify your question. Obviously you have something in mind.

AUDIENCE: I was concerned about everybody investing in a particular, say, asset classes.

MERTON: Yes, thank you for your question, because now you give me a chance to emphasize the point. That point is that there are all kinds of asset classes underneath. But the people making decisions by that are the professionals who are doing the optimization.

You're not sending people 20 or 100 page prospectuses or sending them things and letting them try to figure it out. So you can use any asset classes you want. And everybody's not doing the same thing, because they have different dates. Everybody has a different place. Everybody has different social security position. Everybody has different incomes. Everybody has different other resources.

So the answer is, as you saw on this design scale, it had to be scalable. So if it's not scalable, that's a design failure. And so the answer is if it's designed right, it is scalable. In principle, everybody could use it.

AUDIENCE: Thanks for a really interesting talk. Some of the mutual fund companies and money management companies that handle 401(k)s and other pension funds for companies are beginning to offer target retirement funds. I wonder if you've looked at any of these products and have a sense of whether they begin to do what you've described as useful.

MERTON: That's a good question. And I'll give you my judgment. And, of course, like many things, the term target date fund, or lifecycle fund is morphing because there's a lot of innovation going on. But the traditional ones, the ones that most of you, if you've seen them, have seen, were ones that said 2040.

And if it's 2040, it gives you a schedule for the next 30 years of the mix between stocks and bonds getting more and more into bonds to that date. And it's a mechanical rule, and when you're in it, that's it.

Now, first of all, my belief is, I have to say this, but I feel pretty comfortable, that the origins of this strategy came from the industry's solution of a problem. They had to come up with some kind of strategy. But at the time, anyway, they didn't want to take the kind of fiduciary responsibility that an advisor was.

So they got a ruling that if they put a mechanical rule in age, then they wouldn't be responsible in the same level. And so, all I will say, I have not seen anything that proves those types of funds have any real optimality to them.

Secondly, as you already saw from my demonstration, they don't do their targets in terms of actual income. They do it for life. They do it in terms of the [INAUDIBLE]. So they're using the wrong risk measures.

Third, because they're not integrated. They don't take account of the other assets that people have. So you have a completely distorted view. A 30-year-old, probably the biggest asset for retirement is future contributions.

So if you put 100% of their accumulation in equities, it's only a small fraction of their total wealth. All they ask you is your age. And finally, because this represents core retirement, not supplemental. You know, the stuff for people who want extra money, and therefore, if you lose it, it's extra money anyway.

But for the real stuff, for core retirement, these are probably the second most important decisions that people make after their health. How would you like to get your medical advice by going on the internet, putting your age, but not your gender, and getting your meds? And for the next 30 years.

I mean go back 30 years, 1980. There are some people in the room, obviously, who aren't even 30. But those of you who are around and can remember, has anything changed since 1980? Would you be comfortable setting the rules for what you're going to invest in something serious for the next 30 years?

That just doesn't strike me as good. Now as I say, what's called that's morphing into other things, thank goodness. But literally, those things are-- I don't see how you could believe that you could solve such a complex problem by just a single statistic, which is age.

AUDIENCE: Somebody ought to be saying that publicly, I guess. Because there's a lot of it going on.

MERTON: Well, I believe this is on the webcast. I don't know. So there's only six other people.

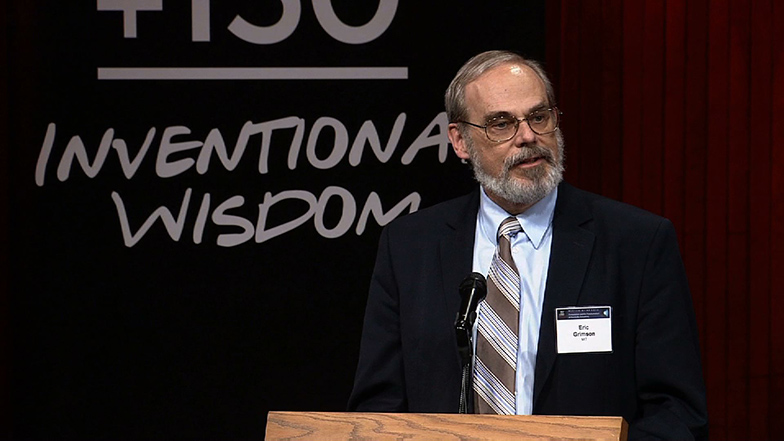

AUDIENCE: You commented earlier, Bob, about the Congress's ready, fire, aim approach to legislating ahead of the problem being solved. I wonder if you could talk to us a few minutes about how MIT and the finance group at Sloan might, over some period of time, have a positive impact.

MERTON: Thank you. By the way, no one from the Sloan School asked you to ask that question, did they? OK, I just didn't want you think we had a shill in the audience. No, I'm glad you did, because that is something I wanted to touch on.

One of the reasons personally that I came back to MIT, because I was a free rider when I wasn't at MIT. I still got to see all the good people because I live in the neighborhood, and they were nice people. And they'll see me.

But one of the reasons I came back was I was very excited about the thrust that the MIT finance group and the school has done in the direction of teaching, creating the MFin program, the Master's in financial track.

Because I think one of the important solutions we have, and it was mentioned earlier today a couple of times, is we need to get many, many more people trained well to address these problems. They're not going to get simpler. They're not going away.

And the answer is not to have people who don't know what they're doing and somehow, even if they're well meaning, even if they're totally ethical, and even if they are totally honest, if they don't have the skill set, like the wrong measure of risk, they can cause a lot of problems. They're not going to solve it.

MIT is committed to producing many more well very, very well trained MIT quality people to go there. Not just the more senior level, we want people to go in as troops at the beginning where they can get experience, but they bring real skill sets.

And this doesn't just apply to the private sector. As you certainly know, all the legislation and everything that's going on has gone in the direction of putting even more tasks in this domain on regulators, the Fed, SEC.

And they need people who are very well trained. Not just as the senior person who comes in charge, but to execute what needs to be done. MIT can do a great job of training such people who can work both in the public and the private sector and globally. And that's where we're going, and that's one of the exciting things that we have going forward.

Obviously, the research side is another. And the third one, which I don't know, I put somewhere in between, but it's the kind of thing that Andrew Lo has done a lot about with this idea of well, what's now recognized as the Office of Financial Research. That may be one of the more important things to come out of Dodd-Frank, which will be an entity that has the right to collect enormous amounts of information from the financial community.

Some of the very things that we're all talking you would need in order to be able to try doing to anticipate either crowded trades, systemic risk, whatever. What are the data that we could get? That has very strong powers, at least it appears to.

But if it doesn't have the abilities to be able to determine what data it can get while maintaining security and analyze the data, and do things with it, it won't come to a hill of beans.

And so I believe that they're going to be a much greater need. MIT can take the role in the education side, the research side, and if you call the OFR computational side. I also would add that this is a great place for collaborative work.

People who have worked in complex systems, people have worked in all these areas. All those skill sets are mostly needed, and needed much more than they ever will be as a consequence.

A word for the regulators, I feel kind of sorry for them sometimes. I think whenever we get a really hard problem, what we do is we write into the bill, the regulators will fix it. As if they were the plug factor that always made everything balanced.

And, you know, that takes resources, and in some cases the tasks that are being asked are far beyond what they are capable of doing.

AUDIENCE: Hi. Thank you very much for this talk. I happen to be with TIAA-CREF, and I'm interested to get your insights on whether you think this evolution will come from the advisory community, from the regulators, or from the fund providers themselves.

MERTON: Good question. I think it will come from all. But I think as usual, people who are entrepreneurial, who are looking for jobs will say, here's an opportunity. And like everything else, if they do a good job developing, and they get people to adopt it, it will work. And if they don't, it won't.

So I suspect people will do this. Maybe TIAA-CREF does this. But people will do this on their selves. I will say I believe that regulators, in my opinion, will generally view this, what I've talked to you about broadly, in a very favorable light.

Because it makes sense. Because it addresses the problem. And it's realistic. It doesn't promise by putting another 100 or 200 basis points that you can solve all the problems. It doesn't assume an 8% risk free rates. It doesn't assume the very things that got us into so much trouble with the DP plans.

Because they were built on another kind of scientific analysis, not that of the markets or finance. And so we had unrealistic expectations. Ones that were doomed to fail. And so, I think if you put forward this sort of thing, that need is a pretty big item.

And the regulators and countries facing this problem see a pretty big need.

AUDIENCE: And this is addressing a few of the issues that was brought up in the first question about say, not working longer or saving more. So could it address that problem to any significance extent if such a plan were defined as an opt out scheme, which everyone is unrolled automatically.

They would have to opt out of it themselves, rather than having people opt into it. Would that perhaps result in higher--

MERTON: Well, I think this is exactly what I alluded to before. The question was, if you have an opt out vs opt in. If you don't know what that is, traditionally in defined contribution plans, when you join as a new employee, one of the forms you sign is, I joined the DC plan.

And, often, the company makes a match, meaning they put it in as much, or more, than you would put in. So, it's obviously for almost everyone a very good deal. But history says that many people don't sign.

We have someone from TIAA-CREF that could probably even comment on that. But there's a lot history that shows the people don't sign anything if they don't have to. It's kind of manana. I'll do it some other.

So the idea came up, which was put into law in the 2006 Pension Protection Act, which allowed what's called an opt out system, which is you have to sign to get out. If you don't sign anything, you're in the plan. So it's reversed it.

The good news is people who didn't sign before to join don't sign to not join. So you get bigger enrollments increased. And that's the whole point of this now that it's becoming core, much more important. All right, what's the bad news?

You're running this fund. The person becomes a new employee. You prepare their first paycheck, and you're taking this money out, right? First of all, how much money you take out? They haven't told you.

So you have to say something. And then what do you do with it? So the point of the matter is you have to have what's called a default. And a default is what happens if you're in the plan, and you don't make any election.

And that's determined by a combination of the sponsor, advisors, and, obviously, regulatory oversight. And that's a very, very important thing. Now, the system I presented to you here generically has the feature that you saw that is probably a pretty good one for default, because it doesn't require the individual to make any asset allocations.

It doesn't find or make any decisions, but it continuously optimizes to a goal. The problem is that the goal we set for them, but that's better than-- it's like your doctor saying, I don't know anything, I'll set your goal at 125 cholesterol. But if you don't sign up, what are you going to do.

AUDIENCE: Thanks for the interesting presentation. Seems to make a lot of sense. I'm curious to know what you see as the leading obstacles or place.

MERTON: I reject the hypothesis of change. You can't expect that people say, oh, that's great. Do it. All right, so you have to work hard to do that. You have a lot of problems with information. I already alluded to the regulatory ones.

You have communications issues. You have people who are saying, please not on my watch, because I don't understand it. All of those things. And maybe there is a better mousetrap. I mean, I'm just saying it.

But I don't see any real reason you can't do this. It's not against public policy. In fact, I think it's perceived as pro public policy. So it's not something where you're going to get intended resistance from the regulators. But the unintended ones are pretty brutal if you don't control it.

AUDIENCE: I certainly share your optimism that the burdens are not as big. Where do you see is most likely the institutional home for the financial knowledge that is going to be needed to drive it? And from my special vantage point there I was sort of seeing two different models.

I saw Ben and Black Rock is a traditional but innovative financial service firm, and then I saw Hal, and the idea that Google, or some sort of an open source home for the financial knowledge. I see it as two separate paths, both of which could try to do the implementation here.

MERTON: That's a good question. Jim, it's good to see you. See, you get good questions from former students who are good students. I didn't plant him either. No, I think we say information. I mean, there's an enormous amount of transaction knowledge, and finance knowledge you need to do this.

You actually have to execute. This isn't an advice engine. And it's very clear. This is a solution. So this isn't something where you have a set of software and people look at it, you say, this is what you ought to do. And then they look at it, and they like it or not, and then they call up.

So if someone else is going to do it, they're going to have to have the expertise to do the dynamics. Maybe I wasn't responding. I mean, you certainly could have a joint venture or something.

AUDIENCE: This is sort of more of the, welcome back to MIT, and the idea that you don't need the innovation on the financial side coming from inside a single shop, but instead the idea that as the system got more complex, it would be through a very open source.

MERTON: So you weren't literally meaning Google versus Black Rock. Or you were.

AUDIENCE: But I would see that I would see Google as hosting the computational power. And then sort of inviting people to come in.

MERTON: So if you're talking about open source, or open architecture, open architecture has many advantages if you're assembling things. The question is, if you are producing, let's say, a car. Let's say, a Mercedes, so we don't use any US ones.

All right, and someone buys the car from you. And they drive it down the block and it stops. Brand new car. Do you think that if that person comes back and you tell them, oh that was a BMW transmission that froze, or those were Perelli tires that went flat.

Do you think your customer is going to be impressed? You're responsible. When you're responsible for the whole product to work as a product, not as a component part. If you're in the transmission business, you say, here's my transmission, go do what you want. Assemble your own 1930s.

You buy the auto body one place. And maybe that's how we do it. There's certainly a lot of stuff done with open architecture. The disadvantage of that, and there's always a disadvantage to every good thing, is that nobody's taking responsibility.

And if somebody is taking responsibility, of course, you can outsource things. That's different. If you do outsourcing where you subcontract where you're the general contractor and you take responsibility, of course.

What you can't do is let somebody else assemble it and you're responsible for it. So if somebody puts what they think is a great asset, or a great transmission in a car, and you don't, but you're responsible for it, I don't think that's a viable model.

So the answer is I think everything works. The right tool for the right job. I have no absolute no problem with open architecture. I think this might be hard to do that way, because of the responsibility factor, particularly because of what this product is.

You're dealing with people's core retirement. Millions of people, if you're successful. So that's why I would say that's an issue that I don't see so easily done, that one. Time? OK. We're done?

Yes, well, thank you the hearty souls who stayed here till the end, I really appreciate it.

COX: I want to thank Bob for the wonderful comments and a great talk. And thank all of you for coming. On behalf of Jim Porterba, Bob Solow, economics department in the Sloan School. Thank you all for being here, and we hope that you'll stay in touch with the department and Sloan. And thank you again for coming. Bye bye.