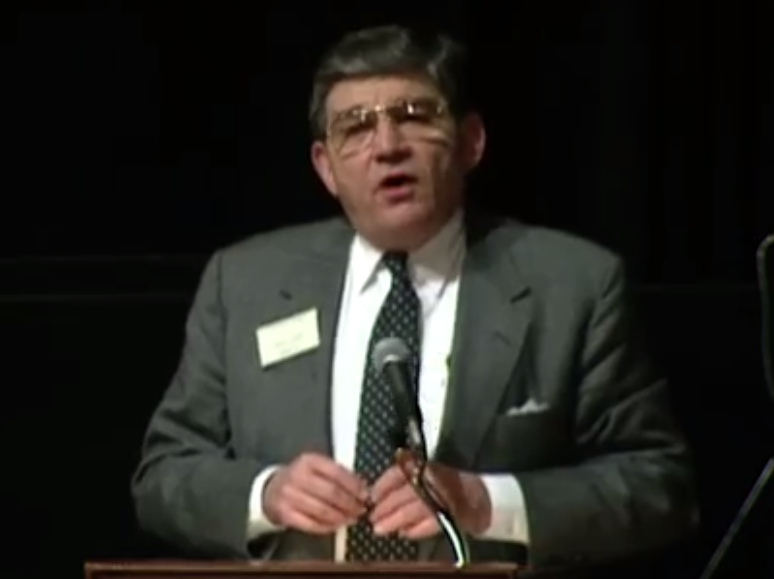

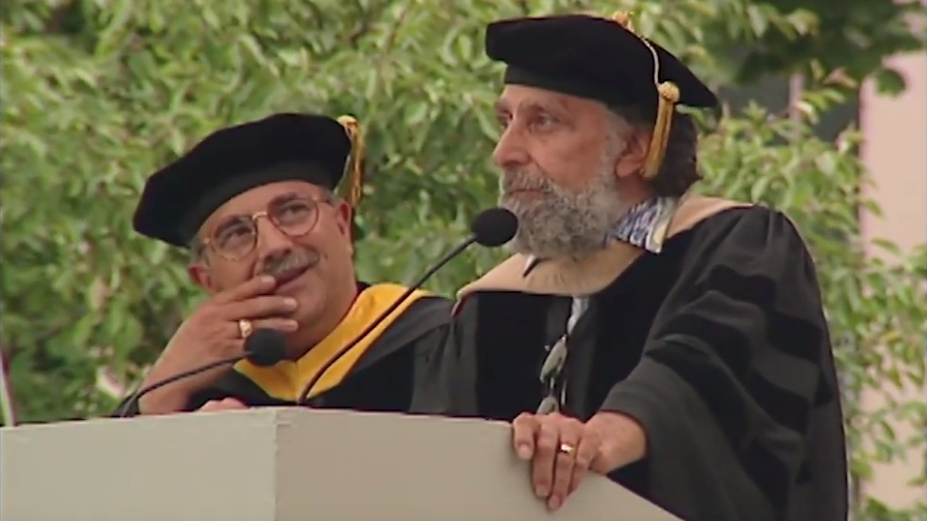

Ben Bernanke (Chairman Federal Reserve) - 2006 MIT Commencement Address

It is now my pleasure to introduce our commencement speaker, Dr. Ben S. Bernanke, the 14th Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Dr. Bernanke is an illustrious graduate of MIT, having received his PhD in economics in 1979. Ladies and gentlemen, distinguished guests, graduates, parents, and graduates to be, Dr. Bernanke. [APPLAUSE] BERNANKE: Good morning. President Hockfield, members of the faculty, alumni, families and friends of graduates, and especially members of the 2006 graduating class, I am honored to speak at the 140th Commencement exercises of this distinguished institution. It's wonderful to be back at MIT. I graduated from the Institute with a PhD in economics in 1979. That year President Wiesner gave the commencement address. He spoke about, among other things, the nation's transition from an era of cheap energy to one of energy scarcity and the need for new technologies to aid in that transition. Obviously, these issues still confront us and one can't help but wonder whether that theme will feel as current 27 years from now as it does today. As for today, you may have been surprised to learn at some point that an economist rather than an engineer or a scientist would be serving as your commencement speaker. But in my remarks, I hope to illustrate that this address continues a long and productive tradition of collaboration at MIT between economics and the engineering and scientific disciplines. Building on that theme, I'd like to discuss the essential complementarity of technology and economics in modern economies. And finally, I'd like to have a few words with you as MIT graduates about what you can do to strengthen our economy and our society even as you pursue your personal and professional goals. If you'll bear with me, I'd like to begin with a short history of economics at MIT. The MIT Economics Department is of course the part of the Institute that I know best and I hope to persuade you that it has played a unique and special role in this institution. MIT's connection to economic dates at least back to 1881 when Francis A. Walker became the institution's third President to say that Walker had already had a distinguished career would be an understatement. He was named a brevet brigadier general at the end of the Civil War at the age of 24. He served as the superintendent of the 1870 and 1880 decennial censuses of the United States and was one of the leading economists of his era. The year he arrived at MIT, he taught the first economics course ever offered at the Institute. The course covered political economy and was so popular that it was soon accorded its own course classification as Course Nine General Studies. Walker helped found the American Economic Association which is still the leading professional association for economists. And during his tenure at MIT, he moonlighted both as the first president of that association and as president of the American Statistical Association. In the early 20th century, the economics program at MIT aimed to prepare undergraduates for leadership roles in business. During those years, economics as a discipline gained greater prominence both here and abroad. But the modern era of economics at MIT began in 1940, the year that Paul Samuelsen, not yet having even received his doctorate, was persuaded to emigrate here from a somewhat less technically proficient institution on another stretch of the Charles River. In part, Samuelson was willing to leave Harvard because his Foundations of Economic Analysis, a book now universally regarded by economists as inaugurating the modern mathematical approach to economics, was not well received by the old guard at the Harvard Economics MIT's PhD program in economics was established a year after Samuelson arrived. And right from the start, the department attracted strong graduate students. The very first of these, Lawrence Klein, received a Nobel Prize for Economics in 1980 for his work in econometric modeling. With support from MIT's administration, the department expanded rapidly after World War II and MIT led the development of a more mathematically rigorous approach to economics. Given the emphasis on quantitative reasoning at MIT, it makes perfect sense that the economics department here was in the vanguard of those using mathematics as a framework for organizing economic thought. These developments laid the foundation for economics as a discipline in the second half of the 20th century and the department quickly rose to the top of national rankings. Besides Samuelson, many economists contributed to the department's outstanding reputation. Franco Modigliani, Robert Solow, Charles Kindleberger, Rudiger Dornbusch, and Stanley Fischer to name just a few. Modigliani, Samuelson, and Solow all won Nobel prizes for their research. And in addition, nine other economists with MIT connections have won Nobels. The MIT Economics Department has trained many economists who have played leading roles in government and in the private sector, including the heads of four Central Banks, those of Chile, Israel, Italy, and I might add, the United States. One of my teachers at MIT, Stan Fischer, is a sterling example of what MIT training can produce. Stan followed a brilliant career as a researcher and a teacher at MIT with important work as a public servant, including top positions at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and, currently, the Bank of Israel. Why did economics at MIT become so successful? Perhaps Paul Samuelson and the people he helped to attract here could have been equally successful anywhere. But I suspect that the placement of economics in a milieu where quantitative reasoning and the scientific method were the coin of the realm was an important contributing factor. The Sloan School with its close links both to the Economics Department and to other parts of the Institute has benefited from the milieu-- [APPLAUSE] --and has been the source of many important and fundamental advances as well. Notably in recent years, the global financial industry has been transformed by quantitative approaches to pricing complex financial instruments, such as derivatives, and the measuring and management of risk. This transformation stemmed from the application of formal tools of mathematical economics that were developed, to a substantial extent, by the faculty at the Sloan School including Fischer Black, Robert Merton, and Myron Scholes, the latter two of whom won Nobel prizes for their work. As MIT economics has benefited from its proximity to the scientific and engineering expertise of MIT, so the Institute has benefited from the presence of a world class economics department over and above the addition of still more luster to the MIT name. The exposure of students and faculty from other disciplines to economics has stimulated creative thinking about how technology can be used to improve the economic welfare of the average person. That thought brings me to my second topic, which is the link between technology and economic growth. As has always been the case, technological change and innovation are today in large part driving economic growth and the improvement of living standards. But it's important to understand that even the very best ideas in science or engineering do not automatically translate into broader economic prosperity. In large measure, the material benefits of innovation spring from complementarities between technology and economics, where I include in economics not only economic ideas, but also economic policies, and even the entire economic system. When the economics is right, scientific and technological advances promote economic development, which in turn, in a virtuous circle, may provide resources and incentives to help foster more innovation. A negative example is the former Soviet Union which certainly did not lack for scientific and engineering talent, but which had an economic system that was poorly suited for translating scientific advances into economic progress. The experience of the United States over the past decade illustrates the essential complementarity of technology and economics. Before the mid-1990s, the growth of productivity, the amount of output produced per worker or per hour of work, had been relatively sluggish for more than two decades in this country. As productivity is perhaps the single most important determinant of average living standards, a country in which an average worker can produce a lot is also typically a country in which an average consumer can consume a lot. The so-called productivity slowdown of that earlier period was the source of much concern on the part of economists and policy makers. The growth rate of productivity increased and picked up in the mid-'90s in the United States and increased still further around the turn of the century. And it remains strong today. This productivity revival augers very well for the future of the US economy. But why did it happen? You graduates of all people will not be surprised to hear that research suggests that the pick up in US productivity growth in the mid 1990s was importantly related to advances in information and communication technologies. But these technical advances in and of themselves can't be the whole story. For example, even though the new technologies are widely available around the world, many other countries appear not to have derived the same benefit as has the United States. Notably, productivity in Europe which increased rapidly in the decades after World War II but then decelerated in the mid 1990s, about the same time that US productivity growth picked up. Thus the gap between the productivity levels in the United States and Europe which had nearly closed by 1995 have been widening. What accounts for the apparent differences in the effects of technology here and abroad? Differences in economic policies and systems likely account for some of the differences in performance, another example of the complementarity of technology in economics. One leading explanation for strong US productivity performance is that labor and product markets in the United States tend to be more flexible and competitive and that these market characteristics have allowed the United States to realize greater economic benefits from new technologies. For example, taking full advantage of new information and communication technologies may require extensive reorganization of work practices, reassignment and retraining of workers, and, ultimately, some reallocation of labor among firms and industries. Regulations that raise the cost of hiring and firing workers and reduce the ability of firms to change work assignments, like those in a number of European countries, may make such changes more difficult to achieve. Likewise in product markets, a high degree of competition and low barriers to entry of new firms in most industries in the United States provide strong incentives for firms to find ways to cut costs and to improve their products. Competition is one of the key benefits of a free and open trade. And companies that are exposed to global competition tend to be more efficient and produce goods of higher quality than companies that are sheltered from international competition. Other economic factors have probably been important in translating technological change into material progress. Some observers point to the depth, liquidity, and sophistication of American financial markets as contributing to recent productivity gains. Sizable markets for venture capital and ready access to equity financing facilitate startup enterprises, which are often the best means of bringing new technologies to market. The United States also benefits from its high quality research universities, which have shown both the willingness and the ability to collaborate with the private sector, and in some cases with the government as well in the development and commercialization of new ideas. For example, Intel was co-founded by an MIT graduate. And MIT graduates have played key roles in designing and developing the internet. One interesting feature of US and global experience with major innovations is that often a significant amount of time passes between the initial development and diffusion of new technologies and the realization of the associated productivity benefits. Computers were first commercialized in the 1950s, for example. And personal computers came into widespread use in the early 1980s. But until the mid 1990s, these developments had little evident effect on measures of productivity. Indeed MIT's Robert Solow famously said in 1987 that computers are everywhere, except in the productivity statistics. Moreover, despite the sharp decline in information technology investment after the meltdown of high sector stocks earlier this decade, the growth rate of productivity has actually increased in recent years, as I mentioned. These long legs raise additional questions about the nature of the links between new technologies and the resulting productivity gains. Perhaps the answer lies in taking the longer view. Some research by economists has drawn an analogy between modern information and communication technologies and earlier so-called general purpose technologies, such as the steam engine, the electric motor, and the internal combustion engine. General purpose technologies have broad application and thus have the potential both to revolutionize methods of production and to make a host of new goods and services available to businesses and consumers. As graduates of MIT, you will be at the heart of this critical process at developing new technologies and, in some cases, taking them to the marketplace. We are in an age in which technology and its fruits will be a dominant force, not only in our economic lives, but in the cultural, social, political, and personal aspects of our lives as well. Your training at MIT equips each of you exceptionally well to take the fullest advantage of the professional and personal opportunities that technological innovation and change will create. Each of you, because of your youth, your talent, your demonstrated commitment to learning, and your personal and intellectual achievements during your time at MIT, will soon find to, paraphrase Shakespeare, that the world is your oyster. I hope that you will contribute in some measure to economic progress, whether in the United States or elsewhere. And I hope you find some measure of financial reward. But the world has a great deal more to offer than money. And a key question each of you will face repeatedly in your lives is how to use the talents and education that you've been given and the knowledge that you have attained. With respect to your professional lives, I hope that when you make career choices, you will look first for opportunities that excite you intellectually, that allow you to use your creative powers to the fullest extent, and that let you continue to learn and grow. I hope you will not be afraid to be unconventional, to do something that nobody else has thought of before. And remember that the paths to success and fulfillment may not be well-marked, the scaling of some predetermined ladder. It may instead be a road without signs and without maps. And remember, it's OK to fail, really. New opportunities will always arise for those who seek them. And if you remain nimble in searching out new and unexpected opportunities, it will not only benefit you but it will also benefit the economy and the society, because long experience has shown that dynamism and creativity are the seeds of innovation and of progress. In the personal sphere as you make your way in the world, I hope you will not forget the importance of your family and how much it has already contributed to your journey through life. Remember, too, family members are the ones who are going to still love you even when things aren't going so well. And even as you focus intensively on your professional interests, I hope you will remain intellectually broad, well-read, well-informed, and open to new experiences. And finally, I hope you will remain engaged with the broader society. That may involve entering public service at some point, as many MIT graduates have chosen to do, but it need not. There are always opportunities to make a difference in the world through volunteering, civic participation, charitable activities, or just the nature of the work that you choose to do. I congratulate all the graduates and your families for what you have accomplished. And let me end by wishing you the very, very best for the future. Thank you very much. [APPLAUSE]